Dave Bunting

Dave Bunting

This edition of JODS comes well-timed following the recent release of a report by NHS Improvement entitled ‘Operating theatres: opportunities to reduce waiting lists’. This report highlights the fact that waiting times for elective surgery have increased year on year since 2012. The lack of inpatient bed availability has a huge impact on these figures and daycase surgery has been identified as an area offering possible solutions. The proportion of cases performed as daycases has increased (now about 70%) and improving theatre productivity will mean that more patients can be treated without adding to rising pressure on beds from emergency care. The report highlighted the fact that individual trusts are succeeding in switching more theatre work to daycase units and moving daycase activity to procedure rooms. There is a wide variation in practice across the country offering great opportunity for further improvement. Increasing productivity by intelligent scheduling to reduce late starts, early finishes and inter-case downtime is something that applies well to the day surgery units. These function separately from other hospital departments and are less prone to eternal pressures than main/emergency theatre environments.

In this edition of JODS, our President, Mary Stocker highlights the many meetings across the UK that BADS is involved in. 2019 is a very special year for BADS during which we will be celebrating our 30th Anniversary. In order to commemorate this occasion, the association will be holding its Annual Scientific Meeting in London at the Royal Society of Medicine. This year promises to deliver an exciting and varied programme highlighting some recent successes and promising future developments in day-case and short stay surgery.

This edition of JODS features scientific articles on a wide range of topics including a report on the introduction of new daycase breast cancer surgery pathways for breast conserving surgery and mastectomy; an audit of pre-operative test recording in elective primary care referrals; a paper demonstrating successful introduction of a daycase hemithyroidectomy pathway; a case series review of the impact of body mass index on management of patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy and a service improvement project in reducing the antibiotic burden for transrectal prostate biopsy.

Whilst reading this edition of JODS, please spend the time to take a look at the advert for the various forthcoming Health Care Conferences UK Events being held in London during March, April and May. In particular, the ‘Developing your Daycase General Surgery Service’ event is being held on Thursday 9th May and is co-hosted by BADS. This promises to deliver an exciting and up to date programme with talks on a range of topics including day surgery pathways, pre-habilitation, paediatric day surgery, emergency ambulatory surgery, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, anti-reflux surgery and 23-hour stay colorectal surgery.

Finally, I would like to remind you that abstract submission for the Annual Scientific Meeting is now open and available via the link below:

https://app.oxfordabstracts.com/login?redirect=/stages/874/submission&dm_i=1O4Y,61VHJ,P49J13,NQY8D,1

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6101/291-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse0

There is as ever a lot going on in the world of day surgery and hopefully you will be able to make it to one of our events over the next few months. Council have been busy collaborating with a number of organisations to develop a varied education programme for our members. In March we are running an event in collaboration with NHS Scotland in Edinburgh, this is a varied programme covering a number of recent innovations within day surgery and is open to all not only our Scottish members. The programme features no less than 4 BADS presidents, past, present and future! In April we are once again supporting an event run by Healthcare Conferences focusing on Hip Surgery. There is a strong day surgery component to the programme. In May once again with Healthcare Conferences we are running an event focusing on innovations in day surgery for general surgery. May also gives you the opportunity to see a little sunshine by travelling with us to the beautiful city of Porto in Portugal, between sampling the local beverage you can attend what looks like a stunning programme at the Congress of the International Association of Ambulatory Surgery. June of course is the highlight of our year - our own Conference. This year is the 30th Anniversary of the founding of BADS and will be our 30th Conference. To mark this we have decided to run the event in London at the Royal Society of Medicine. Hopefully this will be easy for many of you to access and registration is now open as is the opportunity to submit abstracts so get your juniors completing those projects and writing them up ready for the March closing date. We are excited to announce that we will be launching our Conference App this year which we are hoping will help us continue to strive towards being more environmentally responsible and ensure that all our delegates are able to navigate the conference events with ease. In April, June and October we are collaborating with the orthopaedic team from Northumberland to run a series of one day conferences focussing on enhanced recovery and implementation of day surgery pathways for arthroplasty surgery. Watching a patient walk out of the hospital only a few hours after undergoing a hip replacement is truly remarkable, a reflection of the teamwork and professionalism that you all strive to bring to the units you work in and the patients you care for.

If that is not enough to keep you busy applications are now open for our Education Grant and details are available on the website. Council are also currently working on a variety of projects including revitalising our website, development of an accreditation programme for day surgery in association with HQIP and working together with the teams from “Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) to ensure that day surgery is prominent within their surgical programmes.

I hope to see you at one of our events in the next few months and remember we will be asking for all members to consider applying for a position on Council in the next few months, please do give this some consideration as this is your Association and the more people who get involved with its organisation the more we will evolve to meet your expectations.

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse1

Authors

Dr Alexandra Humphreys Specialist Registrar in Anaesthesia

Dr William Hare Core Trainee in Anaesthesia

Miss Jacqueline Rees-Lee . Consultant Oncoplastic Breast and Plastic Surgeon

Mr Michael Green Consultant Breast and Oncoplastic Surgeon

Dr Mary Stocker Consultant Anaesthetist

Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Torbay, United Kingdom.

Abstract

Introduction: The British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) recommends that 95% of conservative breast cancer surgery and 50% of mastectomies for breast cancer are performed as day case.

Despite Torbay Hospital being one of the top performers in the country for day case rates for most procedures, in January 2015 we were ranked in the lowest quartile nationally for day case rates for breast cancer surgery.

We present our strategy for revolutionising our day case breast surgery service.

Methodology: A multidisciplinary team developed day case pathways for patients undergoing breast cancer surgery. In January 2015 the pathway for conservative surgery was introduced. The pathway for mastectomies was introduced in January 2017.

Results: Between 1st January 2015 and 30th September 2017, the day case rates for conservative surgery improved from 16.5% to 97.8%. During the same time frame, the rates for mastectomies improved from 0% to 85.7%.

Between 1st October 2015 and 30th September 2017, 350 procedures were successfully performed as a day case. Follow up data exists for 288 (82%) of these patients; 100% of these patients were satisfied with the day surgery service provided.

National benchmarking for day case rates now rank us as 14th for mastectomy, 3rd for wide local excision of breast tissue and 2nd for sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Conclusion: By introducing these pathways, we have revolutionised our service, achieved the BADS day case targets and are now one of the top performers nationally.

Introduction

Performing breast cancer surgery as a day case procedure is safe, and is well tolerated by patients (1). Patients undergoing breast cancer surgery experience less psychological distress when treated as a day case patient, as opposed to an inpatient (2).

The British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) directory of procedures recommends that 95% of conservative breast cancer surgery and 50% of mastectomies for breast cancer are performed as day case (3).

Torbay Hospital has an outstanding day surgery unit (DSU), and is one of the top performers in the country for day case rates for most procedures. However, in January 2015, the day case rates for breast cancer surgery were significantly below average. Over the previous 12 months, only 16.5% of patients undergoing breast conservative cancer surgery, and 0% of patients undergoing mastectomies, were performed as day case. At the time we were ranked in the lowest quartile nationally for day surgery rates for all benchmarked breast cancer procedures (4). Day case pathways existed for many other procedures, but not for breast surgery, and so the decision was made to develop two separate pathways for patients undergoing breast cancer surgery, these being conservative breast procedures or mastectomies.

We shall herein describe the process by which we transformed our day case breast surgery processes, and the results that we have achieved.

Methodology

We convened a multidisciplinary team consisting of medical and nursing staff from both the breast-care and DSU. Together, we developed the ideal pathway for day case breast cancer patients. Key to this was shared learning between the teams, both of whom had invaluable expertise essential for the development of a successful pathway. In January 2015, we introduced the pathway for conservative breast cancer surgery. This included procedures such as wide local excision of breast, sentinel lymph node biopsy and axillary clearance, but did not include mastectomy surgery. In November 2016, the team went to the ‘Breast Surgery as Day Surgery’ conference, a joint conference run by BADS and Healthcare Conferences UK. Here, the team found out about the best practice across the country, in particular day surgery mastectomy pathways; this gave us the incentive to further develop our day case breast cancer pathways to include mastectomies. We introduced the day case pathway for mastectomies in January 2017.

Patients undergoing breast reconstruction were not included in the pathways nor dataset discussed here as this surgery is unlikely to be undertaken on a day-case basis.

Pathways

Although the pathway for breast conservative surgery is distinct from the pathway for mastectomies, both share salient features, and so they will be discussed as one here.

Pre-surgery

The day surgery pathway begins with a ‘one-stop’ clinical process. The surgical team see and consent patients in a dedicated ‘results clinic’. Once a decision has been made they complete the consent process and are automatically allocated to a theatre list as a day case.

The breast care nurses then see each patient. Patients receive information leaflets, and education about analgesia, mobility and nutrition. Where relevant, patients receive education on drain management; this is demonstrated to them, together with advice about how to look after the drain. Patients are also fitted with a support bra to be worn day and night post-operatively, and mastectomy patients are fitted for a prosthesis.

Patients then go immediately from the surgical clinic to the day surgery pre-operative assessment clinic. Our experience has shown that having pre-operative assessment provided by specialist day surgery pre-operative assessment nurses is essential for ensuring patients are adequately prepared for their day surgery pathway. A senior day surgery anaesthetist is available to directly support the nurses when more complex decisions are needed.

Day of surgery

Patients are admitted via the surgical admissions ward. Localisation procedures (wires, skin marks and radioisotope injections) are scheduled as part of the pathway to minimise theatre delays. Preoperative analgesia with paracetamol is routine. Anxiolytic pre-medication is not given.

We anesthetise patients using techniques that give a rapid onset and offset with a clear-headed emergence; in this unit, we use total-intravenous anaesthesia for the majority of patients. Patients receive generous infiltration of local Levobupivicaine at the surgical site. Surgical drains are only inserted if deemed absolutely vital; their insertion is the exception, not the rule.

Recovery staff in the DSU provide immediate post-operative care. DSU staff have been trained by the breast care unit specifically with regards to drain management, dressings and appropriate bras. Discharge from the DSU is nurse led. The breast care nurses are available to provide support to DSU if needed.

DSU staff discharge all patients with analgesia, 24 hour contact information and wound care advice. If a drain has been inserted then, DSU staff give patients an information booklet, drain bags and appropriate waste bin, and organise drain removal.

Post-operative

On discharge from the DSU, patients are given a telephone number to call in case of concerns. During 0800-2000, this reaches the DSU discharge ward; out of hours, patients are directed to the clinical site manager. Here, advice is given and the relevant teams are contacted if re-admission is required.

DSU staff make a telephone call to all patients on the first day post operation. The call assesses general wellbeing, pain, nausea and other symptom, and advice is given for any specific problems. Patients are signposted to the breast care nurses if any psychological concerns are identified. Any patients that have been discharged with a drain in situ are telephoned by the ‘medical admissions team’ (a service run by the hospital providing care to patients at home) daily until the drain is removed.

Patients have open access to contact the breast care nurses., who run daily ‘drop-in’ clinics. The breast care nurses provide ongoing support if patients are experiencing post-operative complications.

Patients attend a wound clinic appointment on day five post operation. After discussion in the MDT, patients attend a post-op results clinic with further wound check.

The success of our new pathways were evaluated by analysis of day case rates published by national organisations (NHS Digital and NHS Model Hospital). We also analysed our trust data collected via our in house electronic patient record system Galaxy Surgery Ócsc to ascertain further detail of day case rates, unplanned admission rates and post-operative patient outcomes.

Article continues after ad.

Results

Breast conservative surgery

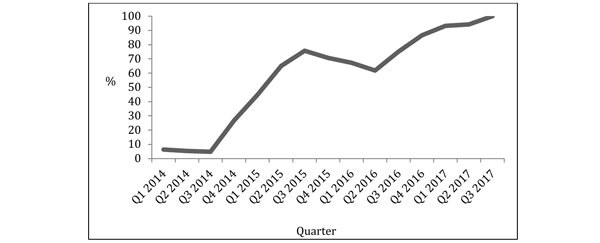

We obtained data for breast care rates from the Clinical Indicators provided by NHS Digital (4). These rates represent the overall day case rate over the preceding 12 month period. On 1st January 2015, the rate of patients undergoing breast conservative cancer surgery as a day case in the previous 12 months was 16.5%. By 30th September 2017, this had risen to 91.4%. Analysis of our trust data for the last quarter of this time period showed rates had risen to 97.8%.

We are now ranked 2nd out of 130 acute trusts for our sentinel lymph node day case rates, and 3rd for our wide local excision of breast tissue day case rates (4).

Figure 1: Rate of patients undergoing wide local excision as a day case per quarter.

Unplanned admission for breast conservative surgery

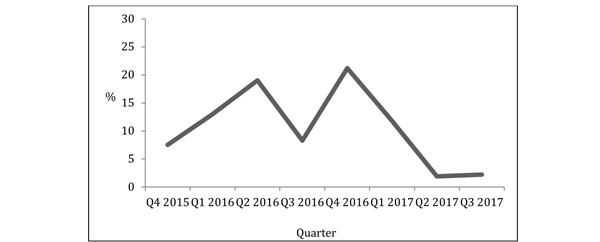

Between 1st October 2015 and 30th September 2017, we performed 404 breast conservative cancer surgeries. 352 of these were booked as a day case. 36 of these patients that were intended to be day case were admitted on the day of surgery, giving an unplanned admission rate of 10.2%. By the last quarter of this time frame, the unplanned admission rate had reduced to 2.2%.

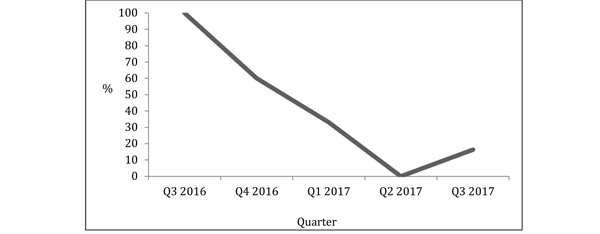

Figure 2: Rate of unplanned admissions for all breast conservative cancer surgery per quarter.

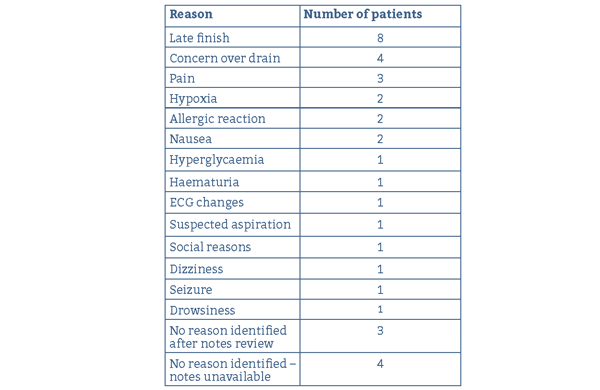

The unplanned admission rate was highest for axillary dissection, with 2 out of 6 patients undergoing this procedure being admitted.

The most common reasons for admission were late finish (8 patients) and concerns about the drain (4 patients). Other reasons for admission included complications such as anaphylaxis and seizures.

Table 1: Reasons for admission for conservative breast cancer surgery.

Mastectomies

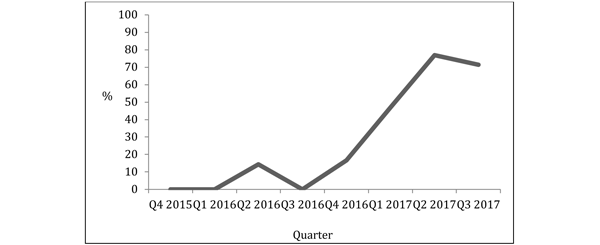

On 1st January 2015, the rate of patients undergoing a mastectomy for breast cancer as a day case in the previous 12 months was 0%; by 30th September 2017, this had risen to 52.4%. During the last quarter of this time period it had risen to 71%, and during the last month it had risen to 85.7%.

We are now ranked 14th out of 130 acute trusts for our mastectomy day case rates (4).

Figure 3: Rate of patients undergoing mastectomy for breast cancer as a day case per quarter.

Unplanned admission for mastectomy

Between 1st October 2015 and 30th September 2017, we performed 130 mastectomies for breast cancer. 48 of these were booked as a day case. 14 of these patients that were intended to be day case were admitted on the day of surgery, giving an unplanned admission rate of 29%. By the last quarter of this time frame, the unplanned admission rate had reduced to 16.6%.

Figure 4: Rate of unplanned admissions for mastectomy for breast cancer per quarter.

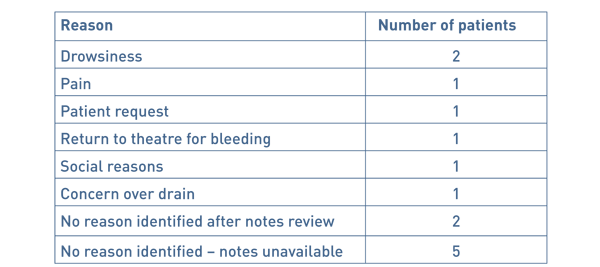

The most common reasons for admission was drowsiness (2 patients). Other reasons included social reasons and return to theatre.

Table 2 Reasons for admission for conservative breast cancer or surgery.

Demographics and post-operative outcomes for successful day case patients

350 procedures were successfully performed as a day case.

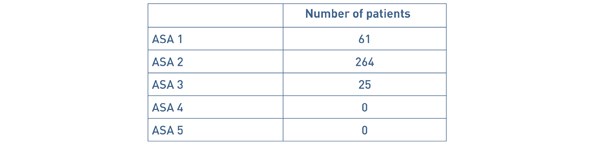

The area served by our hospital has a high proportion of elderly people; 31.00% of the local population are aged 70 years and over, compared with a national average of 25.23% (4). The age of patients that were successfully treated as a day case ranged from 23 – 99 years. 35 patients were aged 80 years and over. ‘American Society of Anaesthesiologists Physical Status Classification’ (ASA) status is shown in Table 3. Our DSU has no cut off for age, ASA or BMI of patients that may be performed as a day case.

Table 3: ASA status of patients successfully managed as a day case.

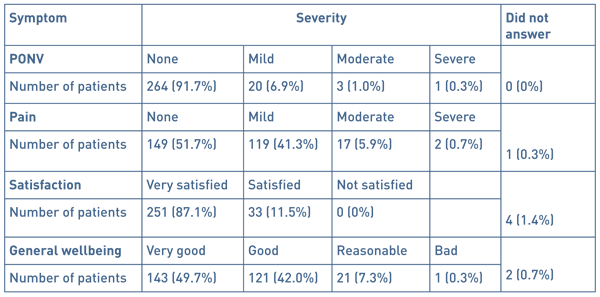

We attempt to contact all patients the day after surgery by telephone. We were able to contact 288 (82%) of the patients. Post-operative symptoms are shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Post-operative symptoms reported by patients.

Discussion

BADS recommends that we should perform 95% of breast conservative surgeries and 50% of mastectomies as day case. By introducing these pathways, we have vastly improved the proportion of patients achieving successful day case surgery for breast cancer. We have exceeded these targets and have improved from one of the poorest performing trusts nationally to one of the top performers. Our comprehensive data shows that this has been safe and that the greater majority of patients are satisfied with their care taking place in a day case environment.

In addition to the recognised benefits to patients, there are benefits to the trust. This pathway has been one of the contributing factors to enabling the trust to close an entire female surgical ward with huge associated financial savings. We also have the ability to continue elective work despite winter pressures of lack of beds and cancellation of all elective surgery. Our patients therefore have a reduction in the risk of cancellation.

Staff involved with the care of these patients feel that there are several aspects that have made the transition work well. This includes the ability to access DSU from the inpatient theatre suite. A significant number of our patients undergo their surgery through our inpatient operating theatres, due to insufficient capacity to meet all our demand in the DSU, coupled with the need to efficiently utilise main theatre time. Patients undergoing surgery in inpatient theatres can transfer to DSU as soon as possible from primary recovery, and then reap the benefits of the DSU. The hard work and commitment from the breast care nurses is invaluable in enabling patients with drains to be managed at home, as well as giving confidence to a vulnerable group of patients. A robust support system with all patients being telephoned post operatively, as well as the ability for all patients to receive rapid access to hospital care if needed, has added to the success. Confidence in staff and hence patients that complications in this type of surgery are rare has helped the transition.

The team feel that the most difficult part of the transformation was the management of patient expectations. The work of the breast care nurses has, again, been invaluable helping this and therefore in enabling the pathways to succeed. Drain management for outpatients was an additional hurdle. Thanks to the support from the breast care nurses, we have been able to insert drains as needed, and have found that discharging patients with drains in situ is safe and acceptable.

Conclusion

By introducing a pathway for patients undergoing conservative breast cancer surgery, and a pathway for patients undergoing a mastectomy for breast cancer, we have dramatically improved our day case rates. Our rates for day case breast surgery are now comparable to our day case rates for most other procedures, whereby we are one of the top performers in the country. We have demonstrated that breast surgery as a day case procedure reduces cost and risk of cancellation, is safe, and that patients treated on our pathways have a high level of satisfaction.

References

- Marla, S, and Stallard S. Systematic review of day surgery for breast cancer. Int J Surg 2009;7:318–323

- Margolese, R, and Lasry, J. Ambulatory surgery for breast cancer patients. Ann Surg Oncol 2000; 7(3):181–187

- British Association of Day Surgery. BADS Directory of Procedures, 5th edn. London: BADS, 2016.

- NHS Digital Clinical Indicators. https://previewer.digital.nhs.uk/ Accessed 15/03/2018.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the breast care nurses at Torbay Hospital for their advice and support in the writing of this paper.

Funding

None declared

Conflict of interest

None declared

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6102/291-humphreys.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse2

Authors

Katharine Davies, Inrid Hinden, Rachel Fletcher & Venkat Srinivasan

Arrowe Park Hospital, Upton, Wirral CH49 5PE

Katharine Davies Specialist Registrar ENT

Ingrid Hinden Foundation Year 2

Rachel Fletcher Foundation Year 2

Venkat Srinivasan Consultant ENT/Thyroid Surgeon

Correspondence: Katharine Davies (07841 125808), c/o Mr Srinivasan: ENT/Thyroid Surgery Department, Arrowe Park Hospital, Upton, Wirral CH49 5PE

Tel: 0151 678 5111 Fax: 0151 604 7403. Email: katdavies33@hotmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Day-case thyroid surgery isn’t routine practice in many hospitals due to fear of potentially life-threatening complications. This single-hospital study reviewed all patients listed for hemi-thyroidectomy as day-cases over a 26-month period assessing what factor(s) influenced successful same-day discharge.

Methods: We analysed notes of patients listed between October 2012 and January 2015 with special reference to delayed discharge, complications and re-admission.

Results: We performed 95 hemithyroidectomies that had been listed as a day-case (81 females, 14 males), 56% were discharged on the same day. Of the 53 patients who were on the morning lists, 79% were discharged home the same day. Of the 42 afternoon patients only 26% were discharged the same day. No patients were re-admitted with haematoma or bleeding.

Conclusion: We show that day-case hemithyroid surgery can be safely performed without occurrence of delayed bleeding or haematoma. The key factors for successful discharge include adequate time for observation post-operatively, low volume thyroids and the intra-operative use of energy sources for haemostasis.

Key Words: Hemithyroidectomy, partial thyroidectomy, day surgery

Introduction

In the current climate of increasing pressure on the NHS, surgeons are continually reassessing their surgical practice and the surgical procedures that can be managed as a day-case without compromising patient safety. This would not only produce cost benefits but also mean fewer cancellations due to lack of inpatient beds and more resources being available for emergency patients. It has been shown to provide greater patient satisfaction and also reduces the risk of hospital acquired infections. (1) Above all else, patient safety is the most important priority for all day-case surgical procedures and therefore, day-case thyroid surgery can only be advocated if patient safety is ensured. The National Health Service set out the plan in 2000 to try and achieve a 75% day-case rate on elective procedures. (2) The British Association of Day Surgery, in 2001, added that we should be trying to achieve a 50% same-day discharge rate for partial thyroidectomy; however this practice does not seem as common in the UK as elsewhere, as less than 1% of all thyroid cases are done in this manner. (3-6)

The main complications leading to concern about day-case thyroid surgery are: hypocalcaemia, recurrent laryngeal nerve damage and delayed post-operative bleeding leading to airway compression. Post-thyroidectomy haemorrhage associated with laryngeal oedema and airway compromise has been reported to occur after 0.9-2.1% of all thyroidectomies. (5) The major argument against day-case surgery is the prospect of delayed bleeding and haematoma after discharge. (6)

Much of the literature on day-case surgery pools together both hemithyroidectomy and total thyroidectomy cases, whereas in our practice we are advocating hemithyroidectomy only to be performed as a day-case procedure in a carefully selected patient population, and there is inadequate information in this select group to arrive at meaningful conclusions. If only hemi-thyroidectomy procedure is considered for its suitability as day-case, the potential complications would be delayed bleeding and haematoma that can lead to airway compromise and one of the main objectives of this study is to assess the occurrence of these events.

In this retrospective study, we have reviewed the data on a group of patients who underwent planned day-case hemi-thyroidectomies in an attempt to ascertain any factors which enabled or precluded same day discharge.

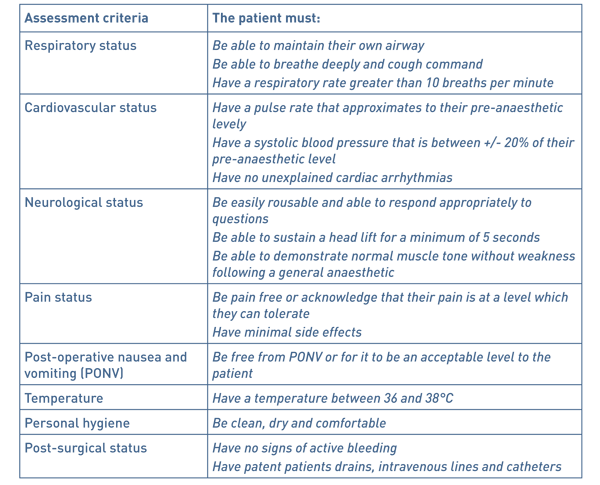

Methods

A retrospective study was completed on data from all patients who had undergone hemithyroidectomy as a day-case procedure between October 2012 and January 2015. All the patients were appropriately consented with explanation of all possible complications. The prospect of delayed bleeding was particularly mentioned and the need to return to the hospital immediately, in case of neck swelling and bleeding, was emphasised. All patients underwent pre-operative assessment to ensure their suitability for day-case care and had their vocal cord movement checked and recorded when being listed for the procedure (Table 1). Patients were admitted to the day-case unit on the morning of the procedure and once again the possible complications were explained to the patients. A standard hemi-thyroidectomy technique was employed and all through the procedure, energy source (Ligasure, Covidien) was used for dissection and haemostasis. When dissecting closer to the nerve, bipolar diathermy was used. Continuous laryngeal nerve monitoring was used in all cases. Drains were used in most of the cases. A continuous prolene suture with beads at both ends was used to close the external wound; this was removed at their local GP practice a week later. Patients were managed post-operatively on the day-case ward. They were reviewed by the senior author prior to discharge. Those with stable observations for 6 hours and without any complication were considered suitable for discharge home into the care of a responsible adult, after fulfilling the day-case discharge criteria. Patients were followed up in the out-patient clinic around 3 weeks or sooner, if necessary. Chi-squared testing was used to see if there was a significant difference between patients operated on in the morning and in the afternoon.

Table 1: Exclusion Criteria for day case thyroid surgery

Total thyroidectomy

No responsible adults at home to care for 24 hours post-procedure

Patients with no access to a car or phone

Patients unable to follow instructions

Fixed or retrosternal goitre

Metastases

Large Goitres

Patients not fulfilling standard day case criteria - medical reasons

Results

A total of 132 hemi-thyroidectomies were performed, between October 2012 and January 2015, by a single surgeon (VS) with 95 fitting the criteria for day case discharge. Of the 95 patients that were included in the study, 14 were men (mean age 60 years with a range of 41-82) and 81 were women (mean age of 52 years with a range of 18-98). 53 patients (56%) were successfully discharged home on the day of surgery with 42 patients having to remain in hospital for at least one night. The reasons for overnight admission are given in Table 2. Out of the 53 patients operated in the morning lists, 42 were discharged home (79%) the same day as compared to only 11 patients (26%) out of the 42 patients from the afternoon lists (p<0.01). The most common reason for overnight admission in the case of afternoon patients was the lack of observation time available. In some cases, a decision was made during the surgery to keep the patients overnight due to intra-operative findings such as difficult dissection, excessive bleeding or adherence due to inflammation. Medical reasons were mainly relating to delayed recovery including nausea and vomiting. One patient developed haematoma immediately after transfer to the recovery and therefore she was taken back to theatre for exploration and haemostasis. There were no readmissions from the discharged group, due to haematoma or bleeding. One patient was assessed in the emergency department on day 7 and found to have a small seroma. She was reassured and discharged home from the department.

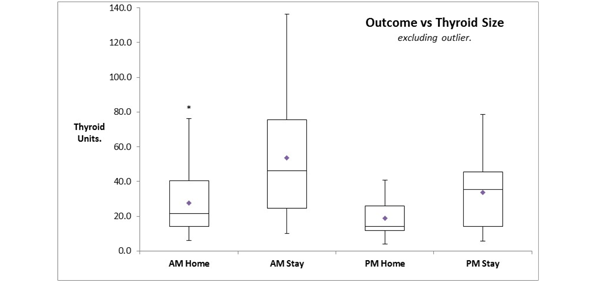

Thyroid size was calculated using the method described by Shabana et al. who multiplied the volume of each lobe by a correction factor of 0.529. This was used as it is not our routine practice to get pre-operative CT scans unless clinically indicated. (7) The thyroid volume was analysed to assess whether this had any impact on discharge. Overall the average thyroid size was 32.8mls. Patients operated on in the morning who stayed at least 1 post-operative day had an average thyroid volume of 50.3mls compared to those who were discharged of 30.8mls. A similar pattern was seen in the afternoon patients with those being discharged home the same day having a thyroid volume of 19mls compared to 33.6mls (see Figure 1). When pooling all the patients together there was a significant difference in size when comparing patients who went home (mean = 26.9, SD= 18.11) and those who stayed (mean = 38.2, SD = 27.5); t (93) = 2.4, p <0.05.

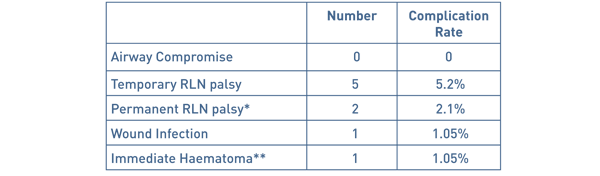

Overall there were 9 complications (9.4%) as documented in Table 3.

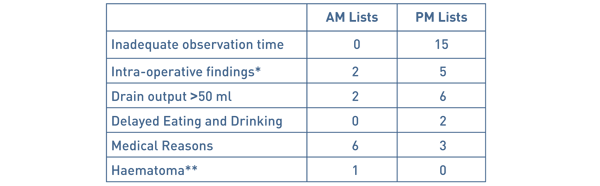

Table 2 Reasons for delayed discharge.

Intra-operative findings* - Significant oozing/bleeding, difficult dissection, fibrosis/inflammation

Haematoma** - One patient developed immediately after transfer to Recovery

Figure 1. Thyroid size in units versus outcome

Boxplot showing minimum and maximum values with 25thquartile, median and 75th quartile. * = outlier and diamond = mean

Table 3 Complications.

* In one case the nerve was embedded in the thyroid cancer and in the second case, in the level 6 nodes.

** One patient developed haematoma immediately after transfer to the Recovery and had to be taken back to theatre for haemostasis.

This patient is included in the Delayed Discharge group

Article continues after ad.

Discussion

Steckler in 1986 and then Mowschenson in 1995 were the first authors to suggest day-case thyroid surgery and came under intense scrutiny and criticism for advocating this.8,9 Steckler performed 48 hemithyroidectomies as day-case procedures of which 4 were kept in due to intra-operative findings. None of the discharged patients were readmitted with complications. Mowschenson successfully discharged 39 hemithyroidectomy patients home after observation of 6 - 8 hours and also had no re-admissions. Since then it has become increasingly popular in clinical practice, particularly in the USA. Some surgeons favour 23-hour surgery and feel this should be the case until strict criteria for patient selection and better research into who is at risk of post-operative bleeding can be ascertained. (5,10)

The main concerns with day case thyroid surgery are unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve damage with dysphagia and possible aspiration in some cases, bilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve damage leading to airway compromise, delayed post-operative bleeding and hypocalcaemia.11 Our study concerns only hemithyroidectomies and the relevant factors against day case surgery would be delayed bleeding and haematoma leading to airway compromise. Multiple authors have shown successful day case thyroid procedures without readmission due to bleeding. Teoh et al. performed 50 hemithyroidectomies with a discharge rate of 98%. (12) Symes et al. successfully discharged 73 out of 75 patients within 8 hours of the procedure.13 The other two were kept for medical reasons. Howat et al. and Terris et al. discharged 75% and 83% of hemithyroidectomies home as day case respectively with no readmissions due to haematoma or bleeding. (14, 15)

The surgical techniques have evolved over time particularly for dissection and for achieving haemostasis. The newer technologies, used for haemostasis, have a significant effect in reducing the post-operative bleeding rate. Historically sutures such as silk and vicryl were used for tying the blood vessels with the potential for slippage and consequent bleeding after a few hours. In the recent years, the use of ties has declined and increasingly energy sources such as Harmonic and Ligasure are employed during surgery. Lepner demonstrated that the use of the LigaSure decreased the operation time with lower drain volume, hospital stay and a lower complication rate. (16) This was felt to be due to the fact that LigaSure delivers precise amounts of energy resulting in less thermal damage to the surrounding tissues such as the RLN and parathyroid glands. Multiple papers add weight to the argument that Ligasure decreased the operating time, ensured adequate haemostasis and they had no re-admissions with post-operative haemorrhage.17-20 Inabnet felt that the use of sutureless vessel ligation was superior over older techniques and that the important consideration was meticulous haemostasis of both the upper and lower pole.19 The paper showed that they only had one haematoma within an hour of the operation in a group of 224 patients but it does not mention whether it was a total or partial thyroidectomy. Interestingly, sutures were not used at all for haemostasis in any of the cases in our series.

Currently there is no consensus regarding the optimal duration of observation in the post-operative period, before the patient can be discharged safely. Delayed bleeding, after 24 hours, has been reported, with Leyre et al having 7 bleeds after 24 hours, however, apart from one case these were all total thyroidectomies. (22) Burkey et al looked at 13,817 thyroid and parathyroid surgeries and showed there to be 18 bleeds within 6 hours, 16 from 6 until 24 hours and 8 cases after 24 hours.23 This being the case it argues against even 23-hour surgery and the patient should stay for at least 24 hours but can this really be justified when there is substantial evidence involving high volume of patients, showing large results with no readmissions due to post-operative bleeding? (11,15)

In 1998 Lo Gerfo et al. performed a review of post-operative bleeding over a 20-year period where they identified 21 cases. (24,25) They found that there was a critical period of time in which most bleeding occurred and in all cases the patient showed signs of bleeding within a few hours and the potential for airway compromise was recognised within 4 hours. This supports the early discharge of patients and is mirrored in our results where no patients were re-admitted due to bleeding or neck swelling. In our series one patient developed significant haematoma but this occurred soon after the patient was transferred to the Recovery and this patient was taken back to theatre for haemostasis. It should be noted that none of the patients in our series developed delayed bleeding after transfer back to the ward or after discharge from the hospital.

As in all surgical disciplines, it is difficult to try and predict which patients will have post-operative bleeding, following thyroid surgery. Leyre in 2008 analysed 6830 cases of which 70 had bleeding post-operatively. (22) They found that age, gender and the type of thyroid disease were not related to haematoma formation. They also found that anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy did not have an influence on bleeding. As regards the timing of the bleeds they found that 37 happened within 6 hours, 26 up until 24 hours and 7 after 24 hours. The majority of these were total thyroidectomies which is not a direct comparison with our study. Looking at their hemithyroidectomy bleeding rates they found that they had 7 (0.4%) within 6 hours, 4 (0.2%) up until 24 hours and 1 (0.06%) after 24 hours. In this paper they do not comment on the haemostatic technique and it could be that the more traditional methods were used.

A parallel can be drawn between day case thyroid surgery and adeno-tonsillectomy. Surgical practice has evolved and changed from the era of keeping adenoidectomy and tonsillectomy patients for several days to the current practice of discharging them on the same day, including the paediatric population. The paper by Leyre et al is quoted by Doran et al as a reason why thyroid surgery should not be done as a day case but when looking at the data and seeing that only 0.3% of all hemithyroid cases had haematoma formation with no further information about these individual cases and the techniques used can it really be the reason to stop all day case thyroid surgery?

Materazzi et al. have devised strict selection criteria for day-case thyroid surgery. (26) Anaesthetic criteria includes ages 10-85, ASA grade 1 or 2, a low intubation score and BMI less than 32. Surgical criteria included primary neck surgery, being euthyroid, gland size less than 80ml and no locally advanced malignancies or intra-thoracic goitres. Social criteria include adequate home support, a suitable living situation and the possession of a telephone. This is a very reasonable selection criteria and is the policy that we adopt with the exception that we do not do total thyroidectomies or children as day case procedures.

We are aware that one of the limitations of our study is the small number but we feel that our series can help arrive at reasonable conclusions, particularly with regard to patient safety. Increasing use of energy sources for dissection and haemostasis has transformed the thyroidectomy surgical procedure in terms of reducing the surgical time and ease of operating. We also feel that the energy sources are helpful in preventing delayed bleeding and haematoma after a reasonable period of monitoring post-operatively. We strongly feel that our number in this study, though small, is adequate to show that with the use of energy sources and adequate post-operative observation time, day-case hemithyroidectomy can be done safely in a selected patient group.

Conclusion

We believe that consideration should be given to perform hemithyroidectomy as day case procedure. Our results have shown that this can be done safely in a reasonable number of patients. We conclude that with careful patient selection and at least 6 hours of post-operative observation day-case hemithyroidectomies can be performed safely. In order to ensure safety, there does need to be strict case selection and thorough information provided to the patients. Our results show that patients operated on the morning lists are more likely to be discharged home on the same day, mainly due to the adequate observation period. It is our opinion that with the use of energy sources for haemostasis and dissection, delayed bleeding can be prevented. In this paper we have shown that with a carefully selected group of patients the overall day case rate can be higher than 50%, as advocated by the British Association of Day Surgery, and can be safely improved upon if operated in the morning. We will continue to audit our practice to assess whether this improved discharge rate continues.

Financial Support

This study received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Sahmkow S, Audet N, Nadeau S, Camire M, Beaudoin D. Outpatient Thyroidectomy: Safety and Patients’ Satisfaction. Journal of Otolaryngology- Head and Neck Surgery. Vol 41. No S1 (April), 2012: ppS1-S12.

- Department of health. The NHS Plan. London: DH; 2000.

- Cahill CJ. Basket cases and trolleys - day surgery proposals for the millenium. Journal of one-day surgery. 1999 ,9. 11-12.

- Sahai A, Symes A, Jeddy T. Short-stay thyroid surgery. Br J Surg 2005; 92: 58-59.

- Doran H.E, England J, Palazzo F. Questionable safety of thyroid surgery with same day discharge. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2012; 94: 543-547

- Doran H.E, Palazzo F. Day-case thyroid surgery. BJS 2012;99: 741-743.

- Shabana W, Peeters E, De Maeseneer M. Measuring Thyroid Gland Volume: Should We Change the Correction Factor? AJR: 186, January 2006

- Steckler RM. Outpatient thyroidectomy: a feasibility study. Am J Surg 1986; 152: 417-419.

- Mowschenson PM, Hodin R. Outpatient thyroid and parathyroid surgery: a prospective study of feasibility, safety and costs. Surgery 1995; 118: 1051-1053.

- Mirnezami R, Sahai A, Symes A, Jeddy T. Day case and short stay surgery: the future for thyroidectomy? Int J Clin Prac 2007;61:1216-1222.

- Snyder S, Hamid K, Roberson C, Rai S, Bossen A, Luh J. Outpatient thyroidectomy is safe and reasonable: experience with more than 1000 planned outpatient procedures. J Am Coll Surg 2010; 210:575-584.

- Teoh AY, Tang Y, Leong H. Feasibility study of day case thyroidectomy. ANZ J Surg 2008; 78: 864-866.

- Symes A. et al. Daycase thyroidectomy. Annual meeting of the British Association of Endocrine Surgeons, Lund, Sweden, 2004. (Abstract)

- Howat G, Weisters M, Sames M, Mclaren M. A Pilot Study of Day Case and Short-stay Thyroid Surgery. The Journal of One-Day Surgery (2006) Vol 16, No 1.

- Terris D, Moister B, Seybt M, Gourin C, Chin E. Outpatient thyroid surgery is safe and desirable. Otolaryngology – Head and Neck Surgery (2007) 136, 556-559.

- Lepner U, Vaasna T. LigaSure vessel sealing system versus conventional vessel ligation in thyroidectomy. Scan J Surg 2007, 96 (1) 31-4,

- Lachanas V, Prokopakis, Mpenakis A, Karatzanis A, Velegrakis G. The use of ligasure vessel sealing system in thyroid surgery. otolaryngol head neck surg march 2005 volume 132 number 3 487-489.

- Schiphorst A, Twigt B, Elias S, Dalen T. Randomized clinical trial of LigaSure versus conventional suture ligation in thyroid surgery. Head & Neck Oncology 2012, 4:2.

- Inabnet WB, Shifrin A, Ahmed L, Sinha P. Safety of same day discharge in patients undergoing sutureless thyroidectomy: a comparison of local and general anaesthesia. Thyroid 2008; 18: 57-61.

- Seybt MW, Terris D. Outpatient thyroidectomy: experience in over 200 patients. laryngoscope 2010; 120: 959-963.

- Rosenbaum MA, Harida M, McHenry C. Life-threatening neck hematoma complicating thyroid and parathyroid surgery. Am J Surg. 2008 Mar; 195 (3): 339-43.

- Leyre P, Desurmont T, Lacoste L, Odasso C, Bouche G, Beaulieu A et al. Does the risk of compressive haematoma after thyroidectomy authorize 1-day surgery? Langenbecks Arch Surg 2008; 393: 733-737.

- Burkey SH, van Heerden JA, Thompson GB, Grant CS, Schleck CD, Farley DR. Re-exploration for symptomatic haematomas after cervical exploration. Surgery 2001; 130:914-919.

- Lo Gerfo P, Gates R, Gazetas P. Outpatient and short-stay thyroid surgery. Head Neck 1991; 13: 97-101.

- Schwartz AE, Clark OH, Ituarte P, Lo Gerfo P, Therapeutic controversy: thyroid surgery – the choice. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1998; 83: 1097-105.

- Materazzi G, Dionigi G, Berti P, Rago R, Frustaci G, Docimo et al. One-day thyroid surgery: retrospective analysis of safety and patient satisfaction on a consecutive series of 1,571 cases over a three year period. Eur Surg Res 2007; 39: 182-188.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6103/291-davies.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse3

Apply for a British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) Educational Grant 2019

‘A multidisciplinary opportunity’

What is it?

Up to two financial awards made to an individual or team to aid a research project or to help fund travel costs as part of a study or practice development (up to a maximum of £1000 but each award to be decided upon by BADS council). In all cases, the project must be aimed at improving day surgery, either within the UK or abroad. A precondition of the educational grant is that those who receive it will attend the a BADS Day Surgery Conference and present the outcomes of their project so that their experience can be shared.

Who can apply?

Applications are open ONLY to BADS members (an application received from a non-member will not be considered). The award is open to any member of the multidisciplinary team or a whole team who wish to be considered for financial assistance. One award will be made available to doctors and one to nursing staff and allied health professionals.

How do I apply?

By submitting a proposal for the work you intend to undertake. This should be presented using the guidelines and application form accessed via our website:

https://daysurgeryuk.net/en/about-us/educational-grant/

Deadline for 2019 submissions: March 30th 2019

Submissions received after this date may be considered for an award in 2020.

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse4

Authors

Reeya Patel, Nida Mushtaq, Huzaifah Haq, Rupaly Pande, & Chaminda Sellahewa

Russells Hall Hospital, Dudley, West Midlands

Corresponding Author: Ms Reeya Patel Flat 16 Jewel Court,, 29 Legge Lane, Jewellery Quarter,, Birmingham, B1 3LE

Tel: 07908 333186 . Email: reeya.patel@nhs.net

Keywords: Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, obesity, day case, operative outcomes

Abstract

Introduction: Obesity is a known risk factor for the formation of gallstones [1] and has a prevalence of 27% in the UK [2]. High body mass index (BMI) has been associated with poorer perioperative outcomes such as increased operative time and a higher incidence of conversion to open surgery though this risk may be an overestimation [3]. The purpose of this study is to evaluate the outcomes and costs associated with day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy (DCLC) in morbidly obese patients.

Methods: A retrospective analysis of patients who underwent DCLC between December 2015 and November 2017 was performed. Anaesthetic and operating times, pre-operative complications, 30-day readmissions and average costs were compared among WHO classifications for BMI.

Results: There were 332 patients who were listed for DCLC. Morbidly obese patients had a longer anaesthetic and operative time of 4 and 8 minutes respectively compared to healthy patients (24 vs 20, p<0.005; 60 vs 52 p<0.001) There was no significant difference in postoperative complications (2 vs 1, p=0.392) cost (£161.96 vs £162.40 p=0.364) or readmissions (8 vs 2, p=0.149) between morbidly obese and healthy patients. There was no difference in length of stay postoperative (0 vs 0, p=0.371) or proportion of successful DCLC (66 vs 62%, p=0.655).

Conclusions: With rising prevalence of obesity in the UK and chronic bed shortages, indications for inpatient admissions in under scrutiny. This study has shown that morbid obesity is not a contraindication to DCLC and is neither associated with worse outcomes or higher costs.

Introduction

In 1980s the UK had an average day case rate of <15% [4] however twenty years later in the year 2000, the Department of Health identified the number one high impact change for Service Improvement and Delivery as ‘treat day surgery (rather than inpatient surgery) as the norm for elective surgery’ [5]. In 2017, day case surgery represents about 70% of all surgery in the United Kingdom [6] with the major drive promoting day case surgery being the advantages of no impatient stay and therefore reduced costs to the National Health Service (NHS) [4]. The Department of Health have developed a benchmarking tool, which is specific to day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy (DCLC); they have advised that 46.8% should be performed as a day case procedure [6].

Day case surgery can be considered for a cohort of patients who have a relatively good physiological baseline where they can undergo a surgical procedure and be discharged home on the same day. Patient assessment for day case surgery falls into three categories: medical, surgical and social factors with obesity categorised as a medical factor [7].

Although many surgeons believe that operating on patients with a body mass index (BMI) greater than 30 is more technically challenging and associated with increased operative complications, this perception is not supported by the literature [8, 9]. The relationship between obesity and operative outcomes remains controversial. Given that obesity is a major risk factor for gallstone disease it appears that a large proportion of patients undergoing DCLC fall into a high BMI category enabling us to explore this relationship [10].

On the contrary, operating on patients with a higher BMI has been associated with an increased operative time and a higher incidence of conversion to open for laparoscopic cholecystectomy [11]. Additionally a high BMI poses a greater risk on post-operative complications such as surgical site infections and post-operative ileus [11].

Despite the healthcare striving towards a shared goal of improving productivity within the NHS, obesity has consistently shown to increase operating time for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy [12,13].

In 2016-2017 the NHS spent a total on £4.5bn [14] on day case surgery where patients are expected to be discharged on the same day. A further £17bn was spent on non-elective inpatient stay which includes patients who are kept in hospital following a planned day case procedure and these figures are rising year on year. When analysing the outcomes of obese patients who underwent a DCLC it is important for us to consider whether we have observed an increase in hospital stay in this category and whether this translates into an increased cost to the NHS.

In our study, we looked at perioperative and postoperative outcomes including mean anaesthetic time, mean operative time, operative complications, postoperative inpatient stay, causes of postoperative inpatient stay, average cost of inpatient stay and rate of successful DCLC for the 5 BMI patient groups (underweight <18.5kg/m2, healthy weight (18.5- 24.9kg/m2, overweight 25.0-29.95kg/m2, obese 30.0-39.9kg/m2 and morbidly obese (>40.0kg/m2).

The study analysed data for 332 patients undergoing DCLC with a BMI range 16.6 kg/m2 to 53.9 kg/m2. The aim of this study is to determine whether operating on a cohort of patients with a higher BMI translates into higher healthcare costs and therefore negatively impact on health expenditure. This would then raise the question whether we need to reassess how we operate on this cohort of patients and do we need to devise more specific guidelines with regards to DCLC and patient selection.

Methods

Patient eligibility

Data from 332 patients who underwent an elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy performed by one of the upper gastrointestinal consultant surgeons at a single district general hospital were analysed. Retrospective data included: age, gender, BMI, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) score, operative time, intraoperative complications, duration of inpatient stay, cost of inpatient stay and readmission. The inpatient stay was the number of inpatient days purely associated with a postoperative day case admission and the readmission rate was calculated using the number of patients readmitted with a postoperative complication within the 30-day post-operative period.

Data was collected from clinical notes in addition to computerised operative notes, which were prospectively maintained between December 2015 and November 2017.

Local eligibility criteria for day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy included symptomatic gallstone disease and an ASA of ≤3, fitness for day case general anaesthesia, performance status ≤2 and an accompanying adult to escort the patient home attend to the patient in the first 24 hours post-operatively.

Operative technique

All laparoscopic cholecystectomies were performed using a standardised surgical approach. All laparoscopies were performed using the 4-port technique with infiltration of 5mls 0.5% bupivacaine prior to each incision.

The patients were positioned supine with an assistant to the right and the senior surgeon to their left. A supra- or infraumbilical incision was made for the optical port and a pneumoperitoneum was created using the open Hasson technique. Once a 30- degree 10mm telescope was introduced via the umbilical port, the remaining epigastric and two right subcostal ports were inserted under direct vision.

The patient was then positioned in a reverse Trendelenberg and left lateral tilt. Dissection started in the Calot’s triangle and completed once the cystic duct, cystic artery and cystic-CBD junction was visualised. The cystic artery was then clipped and divided. A trans-cystic cholangiogram was obtained for each patient and after applying a Rhoder’s knot, the cystic duct was also clipped and divided.

The gallbladder was dissected from the liver bed and retrieved via the umbilical port in a Bert’s bag. Once haemostasis achieved, all ports were removed under direct vision and 10mls of 0.5% levobupivacaine were used to infiltrate the liver bed.

An anaesthetist accompanied patients to day case theatre recovery and once they met local day case theatre recovery discharge criteria (see Table 1) they were discharged home. If there were any post-operative complications or they did not meet recovery discharge criteria the patient was admitted to the surgical ward.

Table 1 Local day case recovery discharge criteria.

Patient data was divided into 5 groups: underweight (<18.5kg/m2), healthy weight (18.5- 24.9kg/m2), overweight (25.0-29.95kg/m2), obese (30.0-39.9kg/m2) and morbidly obese (>40.0kg/m2).

Post-operatively data was collected retrospectively to determine whether patients were deemed unfit for discharge from day case recovery or whether patients were re-admitted within 30 days with post-operative complications.

Data was stored in SPSS software where the Mann Whitney-U statistical tests was run on the anaesthetic time, operative time and hospital cost data sets and the Chi-squared test was run on the gender, postoperative admission and readmission data sets.

Results

Data for 332 patients who underwent a day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy between December 2015 and November 2017 was collected.

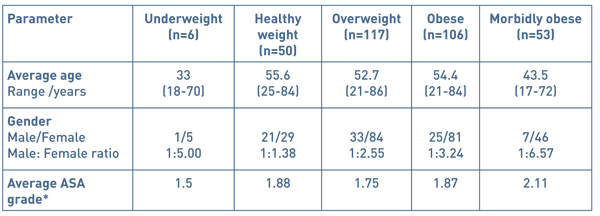

Demographic data included age of patients, male to female ratio and average ASA grades within the five BMI patient groups (see Table 2). The mean age of patients was 51.8 years (range 17-84 years). 245 out of the 332 patients were female (72.92%) and there were significantly more females than males in various patient groups: firstly, the obese BMI patient group in comparison to the healthy BMI patient group (p=0.019) and the morbidly obese BMI patient group in comparison to the healthy BMI and overweight BMI patient groups (p= 0.001 and 0.033 respectively).

Table 2 Demographic data of 332 patients undergoing day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy

* American Society of Anaesthesiologists physical status classification system:

ASA 1- a normal healthy patient

ASA 2- a patient with mild systemic disease

ASA 3- a patient with severe systemic disease

ASA 4- severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life

ASA 5- a moribund patient that is not expected to survive 24 hours with or without an operation

Table 3 Indication for day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy

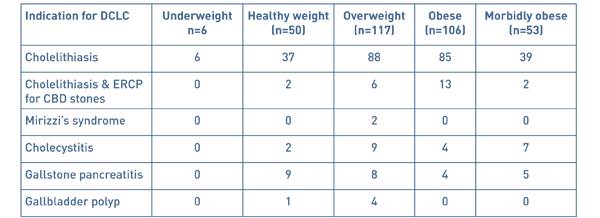

There were several indications for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, the most common being biliary colic and the rest more severe complications of gallstone disease (see Table 3).

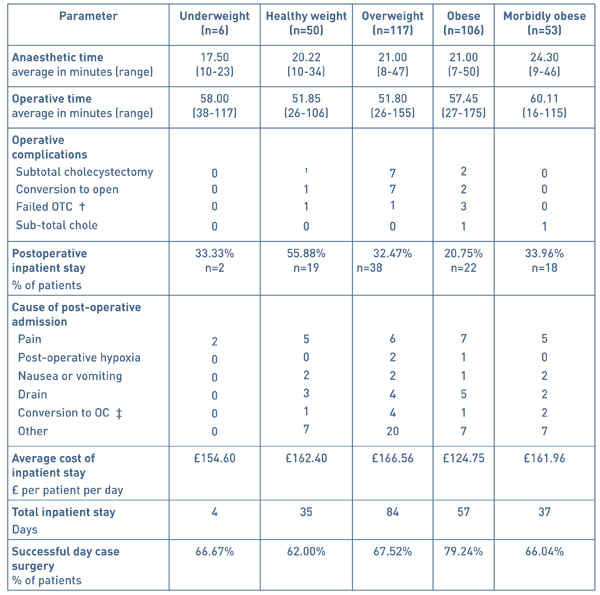

Perioperative and postoperative outcomes included mean anaesthetic time, mean operative time, operative complications, postoperative inpatient stay, causes of postoperative inpatient stay, average cost of inpatient stay and rate of successful DCLC for the 5 BMI patient groups (see Table 4).

Table 4 Perioperative and postoperative outcomes of 332 patients undergoing day case

laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

†: on table cholangiogram ‡: open cholecystectomy

Anaesthetic time data was analysed using the Mann Whitney-U test and ranged from 7 to 50 minutes. Patients who were morbidly obese (BMI ≥40) took significantly longer to anaesthetise in comparison to the underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obese patients (p=0.015, 0.001, 0.004 and 0.001 respectively).

The operating time was measured as knife-to-skin to the completion of the laparoscopic cholecystectomy and ranged from 26 to 175 minutes. Data for operating times were analysed using the Mann Whitney-U test and resulted in significant differences amongst the various BMI groups. The operative times for morbidly obese patients were significantly higher compared to the patient s from the BMI groups: healthy weight, overweight and obese (p= 0.001, 0.001 and 0.046 respectively). In addition, the operative time for patients in the obese weight patient group was significantly greater than the patients in the overweight patient group p= 0.009. The most frequent operative complication was a conversion to an open cholecystectomy and occurred mostly in the overweight BMI group with 6% being converted to an open procedure.

Day case laparoscopic was successful in 70.2% of patients with 233 out of 332 patients being discharged home on the same day of their operation and the remaining 99 requiring a post-operative hospital admission.

The cost of an inpatient stay per night accounted to £232.00 and means were calculated per BMI group using the total number of days of admission for each group. The BMI group, which on average cost the hospital the greatest, was the overweight group (£166.56 per patient per day, n=117) due to a total of 84 days of hospital admission in the immediate post-operative period. The patients from the healthy weight BMI group cost significantly more than from the obese weight BMI group with a mean difference of £37.65 per patient per day.

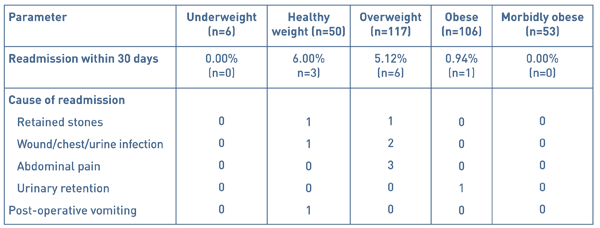

10 patients out of 332 were readmitted to hospital within the 30-day post-operative period (see Table 5). Of these, none were readmitted from the underweight BMI group and the majority (6 patients) from the healthy BMI patient group with a readmission rate of 6%. There was no significance between the readmission rates amongst the five patient BMI groups.

Table 5 Hospital readmissions and cause of readmission within the 30-day post-operative period

Discussion

Worldwide obesity has tripled since 1975 with recent data from the World Health Organisation showing a staggering 1.9 billion adults classified as overweight and of these 650 million obese in 2016[15]. In view of the exponential increases in obesity worldwide, particularly in the United Kingdom, does an increasing overweight population pose additional stress on the deficient NHS budget?

In view of health economics, several studies have looked into the cost impact of obesity on healthcare costs. Sturm et al. found that within the United States, obese adults have on average 36% higher annual medical costs in comparison to those of a healthy weight [16] with Cawley et al. estimating the surplus at approximately $2,741 per person [17].

The Department of Health highlights day case surgery as a means to improve efficiency within the NHS to firstly reduce bed days and secondly reduce other complications associated with inpatient stay such as nosocomial infections and venous thromboembolic disease. Although patient selection for day case surgery has been outlined in national guidelines [4], no numerical cut-off for BMI has been specified leaving us with the crucial question is operating on obese patients less cost and time efficient? Although several studies have proved that operating on obese and morbidly obese patients can lead to longer operating times and higher postoperative complications, we are the first study to look into the cost impact of these on the hospital expenditure.

As the Office for Budgetary Responsibility has projected in their latest Fiscal Sustainability Report health spending is likely to rise significantly as a proportion of gross domestic product over the coming decades, as a result of demographic pressures but also growing technology costs and rising demand [18]. Therefore, examining the cost of operating on this cohort of patients becomes of paramount importance given the current economic climate.

The following perioperative and postoperative outcomes for patient cohorts of varying BMIs will be discussed and whether performing elective DCLC on obese and morbidly obese patients bears any significance on medical costs.

Anaesthetic time

Anaesthesia of the obese and morbidly population can prove technically challenging due to a large tongue, excessive pharyngeal tissue, a high anterior larynx and restricted atlanto-occipital flexion and extension [19]. Of particular concern, patients with features suggestive of obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome, more common in the obese population, can imply potential airway obstruction once the patient has been rendered unconscious [20]. As can be relayed from this study’s results, patients in the morbidly obese BMI groups (BMI ≥40) have taken significantly longer to anaesthetise than patients in the underweight, healthy weight, overweight and obese BMI groups (p= 0.015, 0.001, 0.004 and 0.001 respectively). Morbidly obese patients are likely to present considerable airway difficulties due to the anatomical difficulties mentioned above, with 15% quoted in the literature as difficult intubations [21]. Interestingly, Brodski et al. studied the intubation of 100 morbidly obese patients to identify the factors that complicate tracheal intubation and found that increasing neck circumference and a Mallampati score of ≥3 led to a problematic intubation [22]. Although statistical differences in anaesthetising morbidly obese patients in comparison to patients with a BMI<40, a difference of 2-3 minutes does not bear substantial clinical significance and in practice does not affect the efficiency of day case theatre.

Operative time

Morbid obesity can be considered a significant risk factor for day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to a well-known association with increases in operative time [11], however this is the first study to assess whether these endpoints translate into greater healthcare costs.

Operative time results are comparable to other studies published in the literature with significantly higher operative times in the obese (mean operative time 57.45 minutes) and morbidly obese (mean operative time 60.11 minutes) patient groups compared with the overweight BMI patient group (mean operative time 51.80 minutes, p=0 .009 and < .001 respectively) [23]. These are likely due to a difficulty gaining access to the abdomen secondary to an increased amount of subcutaneous fat and difficult dissection of the gallbladder secondary to a greater amount of omental fat [23]. In reality, the difference in the mean operating time of 8.26 minutes between the morbidly obese and healthy weight patient groups is unlikely to cause significant disruption to an elective day case list due to other influencing factors such as anaesthetic time and pre-operative preparation time. Despite this discrepancy of operative time between the patient groups, literature suggest that converting to an open procedure for obese patients does not improve operating times nor patient recovery post-operatively and in fact, the laparoscopic approach is favourable for these patients [24, 25].

Operative complications

The overall conversion rate to open for this study was 3.01% that is on par with the conversion rate of 3.9-6.0 % cited in recent literature [23, 26]. Out of the 10 patients where laparoscopic surgery was converted to open, 7 were from the overweight patient group.

Postoperative admissions

This study highlighted that there is no significant increase in overnight stay post-operatively in the obese and morbidly obese patients. In fact our study showed a significantly higher admission rate for the healthy weight group when compared to the obese patient group (p=0.224). As one may predict, the majority of patients required an inpatient stay due to post-operative pain particularly after a conversion to open cholecystectomy and post-operative nausea and vomiting.

Admission cost

Admission costs were calculated using the total number on days of hospital stay per BMI group and the highest costing group was the overweight group with an average cost of £166.56 per patient per day. Surprisingly, the average cost of postoperative inpatient stay from the healthy weight BMI group was significantly greater than the obese weight BMI group (p=0.049). These results are contrary to the findings of an extensive systematic review carried out by Tsai et al. who estimated incremental medical costs of overweight as approximately $266 higher, and of obesity $1,723 higher, than that of normal weight persons [27]. However comorbidities associated with obesity such as hypertension and diabetes are more likely causes of these higher medical costs as opposed to elective surgical procedures. What our study concludes is that performing an elective DCLC is no more costly on patients with a BMI of >30 in comparison to those of a healthy weight.

Readmissions

In the post-operative period patients were followed up for a readmission within 30 days and of the 332 patients, 10 patients were readmitted giving a readmission rate of 3.01%. Most patients were from the overweight BMI patient group (n=6): 3 patients were readmitted due to post-operative pain, 2 due a surgical site infection and 1 patient due to a retained common bile duct stone. Of the remaining 4 patients; 1 patient was admitted with post-operative vomiting, 1 with acute urinary retention, 1 with a retained common bile duct stone and lastly 1 with a surgical site infection.

There were no significant difference between readmission rates amongst the 5 BMI patient groups and interestingly no patients from the morbidly obese patient group were readmitted. These results however do not take into account any post-operative complications that may present within the community and treated without an admission.

Despite this, our study shows that although 47.89% of patients who underwent a DCLC had a BMI of ≥30, there was no impact on overall costs of treating these patients when taking into account postoperative admissions into hospital.

These findings demonstrate that morbid obesity is not a hindrance to elective day case surgery lists and that with adequate preparation, operating on these patients is as efficient as patients with a healthy BMI.

Article continues after ad.

Conclusions

DCLC should be performed in patients with a higher BMI. Obesity can have an impact on the anaesthetic and operating times of a day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy however this in turn makes no significant difference to the rate of postoperative admissions, readmissions and most importantly cost. Our study suggests that as surgeons we should disregard the hesitancy towards performing elective day case procedures on high BMI patient as they do not lead to poorer surgical outcomes and crucially, they do not incur higher medical cost. The fundamental point to take away from this study is that although there is an evident increase in the prevalence of obesity it bears no influence on efficiency within the NHS with regards to the hospital costs of elective DCLC.

References

- Erlinger S. Gallstones in obesity and weight loss. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2000; 12: 1347–1352

- NHS Digital. Statistics on obesity, physical and activity [Internet]. National Statistics; 2017 [cited 2017March30]. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/613532/obes-phys-acti-diet-eng-2017-rep.pdf

- Vaughan J, Gurusamy KS, Davidson BR. Day-surgery versus overnight stay surgery for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 7: CD006798.

- Day surgery development and practice: key factors for a successful pathway. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, 2014, 14 (6):256–261

- Quemby DJ, Stocker ME, Day Surgery Development and practice: key factors for a successful pathway. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain, Volume 14, Issue 6, 1 December 2014:256–261

- NHS England. 10 High Impact Changes for Service Improvement and Delivery [Internet]. NHS Modernisation Agency; 2004 [cited 2018Mar29]. Available from: https://www.england.nhs.uk/improvement-hub/wp-content/uploads/sites/44/2017/11/10-High-Impact-Changes.pdf

- Verma R, Alladi R, Jackson I, Johnston I, Kumar C, PageR, Smith I, Stocker M, Tickner C, Williams S, Young R. Day case and short stay surgery: 2, Anaesthesia 2011; 66: pages 417-434

- Reeves BC, Ascione R, Chamberlain MH, Angelini GD. Effect of body mass index on early outcomes in patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:668–76

- Dindo D,Muller MK, Weber M. Obesity in general elective surgery. Lancet 2003;361:2032–5

- Bonfrate L, Wang DQ, Garruti G, Portincasa P. Obesity and the risk and prognosis of gallstone disease and pancreatitis. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014 Aug;28(4):623-35

- He Y, Wang J, Bian, H, Deng X, Wang Z. BMI as a Predictor for Perioperative Outcome of Laparoscopic Colorectal 4. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy in obese and nonobese patients. Obes Surg. 1999 Oct;9(5):459-61

- Surgery: A Pooled Analysis of Comparative Studies. Diseases of the Colon & Rectum. 60. 433-445. 10.1097/DCR.

- Subhas G, Gupta A, Bhullar J et al. Prolonged (longer than 3 hours) laparoscopic cholecystectomy: reasons and results. Am Surg. 2011 Aug;77(8):981-4.

- NHS Improvement. Finance and use of Resources [Internet] NHS England 2017. [cited 2018Apr07]. Available from: https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/reference-costs/

- World Health Organization. Obesity and overweight [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2018 [cited 2018Mar29]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/

- Sturm, R. The effects of obesity, smoking, and drinking on medical problems and costs. Obesity outranks both smoking and drinking in its deleterious effects on health and health costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2002 Mar-Apr;21(2):245-53.

- Cawley J1, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: An instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012 Jan;31(1):219-30.

- Office for Budget Responsibility. Fiscal Sustainability Report [Internet] OBR. 2017. [cited2018Apr07] Available from: http://cdn.obr.uk/FSR_Jan17.pdf

- Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK. Anesthesia and obesity and gastrointestinal disorders. Clinical Anesthesia, 1992: 1169–83.

- Adams J, Murphy P. Obesity in anaesthesia and intensive care. British Journal of Anaesthesia, 2000 July(85): 91–108

- Buckley FP, Robinson NB, Simonowitz DA, Dellinger EP. Anaesthesia in the morbidly obese. A comparison of anaesthetic and analgesic regimens for upper abdominal surgery. Anaesthesia. 1983 Sep;38(9):840-51.

- Brodsky, Jay B. Lemmens, Harry J. M., Brock-Utne, John G., Vierra, Mark, Saidman, Lawrence J. Morbid Obesity and Tracheal Intubation. Anesthesia & Analgesia: March 2002 - Volume 94 - Issue 3 - p 732-736

- Malla BR1, Shrestha RK. Laparoscopic cholecystectomycomplication and conversion rate. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ). 2010 Oct-Dec;8(32):367-3369.

- Harju J, Juvonen P, Eskelinen M, Miettinen P, Pääkkönen M. Minilaparotomy cholecystectomyversus laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a randomized study with special reference to obesity. Surg Endosc. 2006 Apr;20(4):583-6

- Miles RH1, Carballo RE, Prinz RA, McMahon M, Pulawski G, Olen RN, Dahlinghaus DL. Laparoscopy: the preferred method of cholecystectomyin the morbidly obese. Surgery. 1992 Oct;112(4):818-22

- Harboe KM1, Bardram L. Nationwide quality improvement of cholecystectomy: results from a national database. Int J Qual Health Care. 2011 Oct;23(5):565-73.

- Tsai AG, Williamson DF, Glick HA. Direct medical cost of overweight and obesity in the United States: a quantitative systematic review. Obesity reviews : an official journal of the International Association for the Study of Obesity. 2011;12(1):50-61.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6108/291-patel.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1557#collapse5

Authors

Matthew Crockett, George Hill, Kim Jacobson & Helena Burden

Southmead Hospital, Bristol, UK

Corresponding Author

Matthew Crockett Department of Urology, Southmead Hospital, Southmead Road, Westbury-on-Trym, Bristol, BS10 5NB

Tel: 07729 092909 Email: crockettmatt@hotmail.com;

Keywords: antibiotic; prostate; biopsy; TRUS; burden

Abstract

Introduction: Antibiotic prophylaxis for transrectal ultrasound biopsy of the prostate (TRUS) is well established. Quinolones are used in many centres. However, the most effective regimen is not known and the choice is based on local resistance profiles. Our local protocol consisted of 750mg ciprofloxacin two hours pre-biopsy, 400mg metronidazole PR post-biopsy and a 5/7-day course of 500mg ciprofloxacin BD.

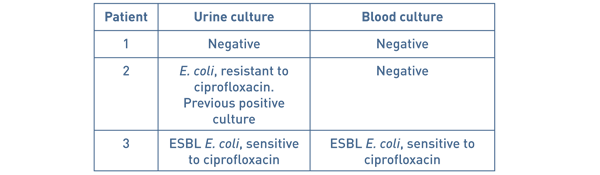

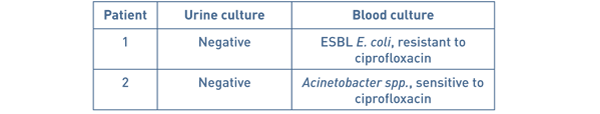

Methods: We retrospectively reviewed 160 consecutive patients undergoing TRUS biopsy over a 3-month period from November 2016 to February 2017. Blood & urine cultures were noted and any positive cultures were reviewed a microbiologist. After liaising with our microbiology department, a new antibiotic protocol was introduced consisting of a single dose of ciprofloxacin 750mg two hours prior to the procedure. A re-audit was then undertaken from September to December 2017 consisting of 109 consecutive biopsies.

Results: With the existing protocol 2 patients (1.25%) had positive cultures; both were admitted with sepsis. Both patients grew E. coli, one was resistant to ciprofloxacin on a previous culture and neither was sensitive to metronidazole.

On the new protocol, three patients (2.8%) had positive cultures. One patient grew E. coli resistant to ciprofloxacin, one Enterococcus and the other grew Acinetobacter. There was no significant difference between the groups.

Conclusions: A reduced and simplified antibiotic protocol does not increase the risk of infection after TRUS biopsy. Patients should be screened for ciprofloxacin resistance prior to the procedure. Patients developing sepsis appear to have atypical or ciprofloxacin resistant organisms on culture. Reducing antibiotic usage could reduce cost, side effects and potentially the development of resistance.

Introduction

Antibiotic resistance has been described as the greatest threat to modern medicine [1].

Transrectal ultrasound guided prostate biopsy (TRPB) is the most commonly used technique for acquiring histology for the diagnosis of prostate cancer. The insertion of needles through the rectal mucosa breaches this natural barrier and can inoculate the prostate with gut commensals, most commonly Escherichia coli (75-90%), Klebsiella pneumoniae & Pseudomonas aeruginosa [2]. Complications occur in up to 50% of patients with 0-9% developing a urinary tract infection (UTI) and 30-50% of these also associated with bacteraemia [3] [4] [5] [6] [7]. Antibiotic prophylaxis reduces the risk of infection but an ideal antibiotic regimen has not been agreed and BAUS advise that regimens should be decided based on local antibiotic resistance profiles [8].