Dave Bunting

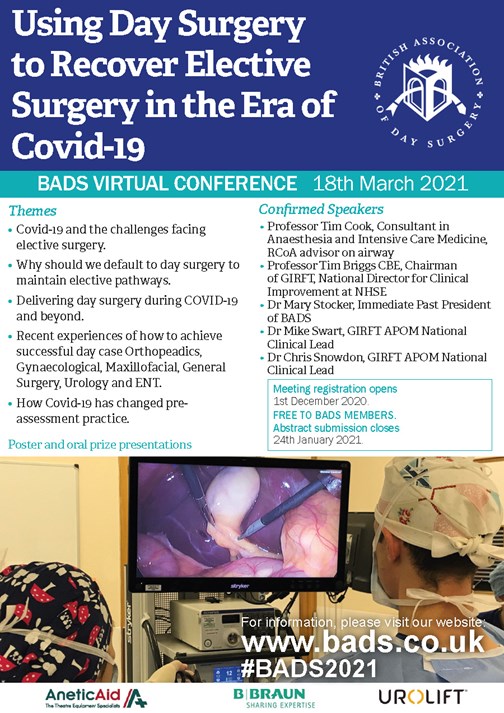

The BADS Annual Conference has now been rescheduled to take place on Thursday 18th March 2021. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, it will be conducted as a virtual conference which will be delivered free of charge to all current BADS members. The one-day virtual conference will focus on how day surgery can be used to recover elective surgery in the Covid-19 era. BADS are encouraging authors to submit abstracts of their work. Abstracts will as usual be peer-review and scored. Accepted work will be presented in e-poster format. There will be gold, silver and bronze awards for high scoring abstracts and the top scoring authors will be invited to deliver oral presentations that will be broadcast during a prize paper session at the conference.

The abstract submission window has been extended with a new deadline of Sunday 24th January 2021. This is the link to abstract submission:

https://app.oxfordabstracts.com/login?redirect=/stages/1625/submissions/new

The importance of day surgery as the major contributor to the future of surgical services and a key to increasing productivity as we work through the Covid-19 pandemic has been recognised by the Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) NHS Improvement Programme, who in collaboration with BADS and the Centre for Perioperative Care (CPOC) have recently published the National Day Surgery Delivery Pack. The pack is designed to enable NHS Trusts to expand and increase day surgery for the benefit of patients and the wider healthcare system. It highlights significant room for improvement with wide variation in day surgery rates across the UK. It makes a compelling case for expanding and increasing day surgery services; it describes the key components of a successful generic day surgery pathway and details procedure-specific best practice pathways and templates. The importance of this initiative is given further credence with the recent news from NHS England Referral-to-Treatment statistics that 100 times more patients are waiting over a year for elective hospital treatment compared to this time last year.

The National Day Surgery Delivery Pack can be found here:

Original papers in this edition of JODS include a review of day-case parathyroidectomy performed in a single institution over a 10-year period; a report on over 400 patients undergoing hysterectomy as a daycase; an investigation into the potential benefits of patients supplying their own post-operative analgesia and a report on introduction of a daycase pathway for total hip replacement.

In this edition of JODS, three updated ‘How I Do It’ day case guides are presented, this month with a Urology theme. They include guides on Green Light Laser Prostatectomy, Trans-urethral Resection of Prostate and Day Case Bipolar Saline Prostatectomy.

Please keep your submissions to the journal coming in and remember – JODS still offers citable peer-reviewed publication with no author processing fees. Author guidelines and submission instructions can be found in this edition of the journal.

Perhaps by the time the next edition of JODS is published in February next year we may be seeing some positive effects of widespread coronavirus vaccination that will help us in the process of restoring day surgery productivity.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/45191/304-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse0

I hope this finds you safe and well. We all continue to face challenges in our work and home lives due to the impact on Covid-19. As you will already know, the NHS has moved up to level 4 nationally which demonstrates the seriousness of the ongoing pandemic and the onset of winter pressures. Day surgery has been highlighted as a solution to aid the recovery of elective surgery and BADS has been invited to join a number of workstreams e.g The NHS England (NHSE) Adapt and Adopt Theatre workstream and the Get It Right First Time (GIRFT) London Recovery of Elective Surgery programme. Both of these workstreams have considered the BADS directory of procedures and how variation in day surgery pathways can be addressed to achieve the target day case rates set by BADS. The GIRFT London Recovery of Elective surgery programme has produced 29 pathways across 6 specialities, promoting day surgery wherever possible.

In September 2020, in collaboration with GIRFT and Centre of perioperative care (CPOC), BADS has published the day surgery delivery pack which we hope will prove informative for anyone interested in delivering day surgery. Education and promotion of high quality day surgery pathways continues to be a key component of the work of BADS and we have also recently published the Day case hip and knee replacement 2nd edition and Day case Gynaecology booklets. September also saw the publication of the Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCoA) 4th edition of Raising the Standards: RCoA quality improvement compendium which includes 9 day surgery quality improvement projects written by BADS council members.

We continue to work closely with Health Care Conferences UK (HCC) and have recently delivered 3 successful day surgery conferences: Day case major knee surgery, Day case hip surgery and Day case gynaecology. On 4th December 2020 we have the Day case general surgery meeting which focusses on how to deliver day case general surgery during these challenging times of the covid19 pandemic. We are privileged to have many high quality speakers, to name a few, Professor Doug McWhinnie, President of the International Association of Ambulatory Surgery (IAAS), Mr Arin Saha, National Lead for Surgical Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC ) and Graham Lomax, GIRFT Deputy national delivery director.

BADS couldn’t do what it does without the fabulous and hard working BADS council. I would like to take this opportunity to thank each and every member of BADS council for their contribution to BADS and the promotion of day surgery. I am delighted to welcome our new elected members of BADS council Matthew Checketts, Cath Jack and Rachel Morris. They have all been delivering and developing day surgery for many years and they will all be a valuable addition to BADS council. If you would like to know more about them, their biographies are available in this edition of JODS. I am also pleased to announce that Sally Leyshon, one of our lay members has agreed to extend her term on BADS council. We also welcome 3 co-opted members, Maire Morton who is a Consultant OMFS surgeon and the GIRFT national lead for OMFS, Tara Byott, representing the Trainee committee of the Association of Anaesthetists and Mohammed Rabie representing Association of Surgeons in Training (Asit). Our co-opted members offer a valuable link to these Societies and aid us to enable promotion of day surgery education and support the delivery of high quality day surgery pathways.

BADS council has recently taken the difficult decision to cancel our face to face conference planned for March in 2021 in Cardiff. Instead we will be holding a one day virtual conference focussing on how day surgery can aid the recovery of elective surgery. Registration will be free for all BADS members so I do I hope you will join us. We already have some excellent speakers who have agreed to speak.

So, looking forward to 2021, I hope it and the Covid-19 vaccine brings us all a good year.

Take care and please keep safe and well.

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse1

Tara Byott

Tara is an LTFT ST5 anaesthetic trainee. She completed her medical degree at The University of Manchester and has continued her training in the North West. Her clinical interest lies in tertiary paediatrics and she hopes to commence advanced training upon return from maternity leave. She is passionate about medical education with a particular interest in simulation training. She has recently been elected onto the AAGBI trainee committee which lead to her role as a co-opted member of the BADS council. She looks forward to working with the team and continuing the strong alliance between anaesthesia and day surgery.

Dr Matthew Checketts

I have been a consultant anaesthetist at NHS Tayside since 1998 and I work at both Perth Royal Infirmary and Ninewells Hospital and Medical School in Dundee. My clinical interests include day case paediatric surgery, trauma and orthopaedics and fast track/enhanced recovery techniques. In 2019, I was granted a 3 month clinical sabbatical which allowed me to visit 10 hospitals in the UK, US and Denmark which was a great source of inspiration as well as personally and professionally refreshing – I recommend others to explore this option. During the Covid lockdown, I started a weekly online eclectic music radio show called Heaven’s Mixtape on Mixcloud that has become my essential creative outlet – give it a try - mixcloud.com/matthew-checketts

Catherine Jack

Catherine ventured north from sunny Cambridgeshire in February 1991 to start her nurse training in Edinburgh at the Western General ill-prepared for the cold, the homesickness, and the fact that people wouldn’t understand her accent! After almost 30 years, she is still happily living in Scotland having ventured across the bridge to the Kingdom of Fife.

She is the Senior Charge Nurse in day surgery theatres at Queen Margaret Hospital in Dunfermline, responsible for eight theatres and almost 60 staff, across a range of specialities. She has an absolute desire to drive day surgery service forward in Fife and aspire to be the leading hospital in Scotland for day surgery learning from colleagues south of the border.

Out with work she enjoys cycling (in the summer), walking her dog, Gordon and good food and wine – she hopes will be offset by the first two!!

Rachel Morris

Rachel is a Consultant Anaesthetist at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital. She graduated from St Mary’s Hospital Medical School, Imperial College, London in 1995. Rachel started her career as a physician and after gaining the MRCP decided to train as an anaesthetist.

Rachel’s clinical interest is gynaecology oncology anaesthesia, vascular anaesthesia, and of course ambulatory surgery. Rachel has had a keen involvement with day surgery during her training and this is when she became a member of BADS. Since becoming a member, Rachel has attended BADS regularly and contributed to conferences and JODS. She has been the Clinical Lead for Day Surgery at NNUH for the last 3 years. She is looking forward to being a Council Member and will hopefully help advance Day Surgery at a local and National level.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/45192/council-members.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse2

Click the image to find out more details about the virtual conference.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/44743/asm-virtual-2021-flyer-v3.png

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse4

IAN SMITH, ANURAG GOLASH & CLARE HAMMOND

(This article was originally published in the Journal of One-Day Surgery Vol. 23 No. 2, 2013. It was Number 4 in the 'How i Do It' series, updated in 2020)

Patient Selection

-

Benign prostatic hypertrophy or carcinoma of prostate

-

Small to moderate prostate (<40 g)

-

Contraindicated if known large middle lobe or raised PSA

-

Typically quite an elderly population with significant co-morbidities, but most will be acceptable provided spinal anaesthesia is not contraindicated.

Anaesthetic Techniques

-

Most patients are managed using a low dose spinal technique

-

We use 6–7 mg hyperbaric bupivacaine with 10 μg fentanyl added made up to 3 ml with saline

-

Patients listen to their choice of music. Sedation is rarely needed, propofol (10–20 mg) can be used for especially anxious patients. We only add oxygen if sedation is used

-

All patients get 240 mg of gentamicin and 1 litre of Hartmann’s solution

-

General anaesthesia with spontaneous ventilation through a LMA is an acceptable alternative where spinal anaesthesia is not possible

Surgical Technique

-

A standard laser prostatectomy technique with saline irrigation is used, this is not modified for day surgery

-

16 French gauge 2 way catheter at the end of surgery (no irrigation)

-

We remove the catheter at 2–4 hours when the spinal has worn off if the urine is clear

-

If the urine is not clear or if trial without catheter (TWOC) fails, patients go home with a catheter for further TWOC at 2 days by district nurse

Peri-operative Analgesia

-

Preoperative oral slow-release ibuprofen, 1600 mg

-

Postoperative regular paracetamol and codeine, if needed

-

With spinal anaesthesia, most patients have little postoperative pain

Take Home Medication

-

Slow release ibuprofen for 3 days

-

Co-amoxyclav for 3 days

Organisational issues

-

Pre operative brief to include PACU staff member as anticipation of individual patient issues hugely valuable in this patient group

-

Day Surgical Unit theatre team experienced in major gynaecological laparoscopic cases with skills that enable conversion to open procedures – staff rotate to main theatres if unfamiliar with open cases.

-

Urinary catheter throughout procedure but removed in theatre prior to reversal of anaesthesia

Common Pitfalls

-

Excessive talking (or laughing or singing!) by the patient can distort the surgical view

-

Take great care to minimise intraoperative bleeding, especially at the start of the procedure. Avoid excessive movements of the resectoscope

-

Postoperative dysuria is common, antibiotics probably do not prevent this but may deter the patient from troubling their GP!

Anticipated day case rates

- 90%

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/44737/hidi-smith_gll-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse5

MARY STOCKER & SEAMUS MACDERMOTT

(This article was originally published in the Journal of One-Day Surgery Vol. 23 No. 4, 2013. It was Number 7 in the 'How i Do It' series, updated in 2020)

Patient Selection

- Select patients who will cope with catheter at home

- Limit to prostates of moderate size

Anaesthetic Techniques

• Spinal anaesthetic:

• 2-3mls (40-60mg) 2% hyperbaric prilocaine

• 1.5mls 0.5% (7.5mg) hyperbaric bupivacaine

• Or short acting general anaesthesia

Surgical Technique

- IV antibiotics at induction

- Standard monopolar or bipolar TURP

- Ensure systolic BP >100

- Close attention to haemostasis

- 3-way catheter for irrigation if needed

- Mobilise after 1-2 hours or spinal block worn off

Peri-operative Analgesia

- Pre-operative: oral paracetamol (1g) and ibuprofen (1600mg slow release)

- Intra-operative: iv fentanyl if spinal not used

- Post operative: regular paracetamol and ibuprofen

- Rescue intravenous fentanyl or oral morphine if required

Take Home Medication

- Paracetamol 500 mg/ codeine 30mg po qds, laxido 1 sachet bd, plus ibuprofen 600 mg po qds

Organisational Issues

- Catheter removed by district nurse next working day before 10am

- Appointment with urology nurses that afternoon after 4pm for symptom check/ bladder scan

- Notes to urology office to await histology

Anticipated Day Case Rates

- 30%

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/44738/hidi-stocker_turp-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse6

SARAH M LLOYD & STUART LLOYD

(This article was originally published in the Journal of One-Day Surgery Vol. 24 No. 1, 2014. It was Number 8 in the 'How i Do It' series, updated in 2020)

Patient Selection

- Benign prostatic hyperplasia or carcinoma of prostate.

- Any size prostate.

- Not contraindicated if known large middle lobe enlargement or a raised PSA suspicious of cancer.

- Typically an elderly population with significant co-morbidities, but most will be acceptable including many ASA 3.

Anaesthetic Techniques

- Most patients have a general anesthetic with spontaneous ventilation through a LMA. This facilitates rapid recovery and early ambulation.

- Some are managed using a spinal technique; due to its shorter duration of block, hyperbaric 2% prilocaine is now the drug of choice for this.

- All patients receive IV gentamicin 2mg/Kg.

- Patients receive 1 litre of IV normal saline solution during surgery and 1 further litre over the 2 hours following.

Surgical Technique

- A transurethral resection (TUR) technique using saline irrigation, which is not modified for day surgery.

- Continuous activation of the loop is best to optimize the cutting potential. Intermittent activation is also an alternative.

- 18 French gauge, Coude tip 3-way catheter with 20ml water to the balloon at the end of surgery. This permits irrigation for 1 to 2 hours if needed.

- The irrigation port of the catheter is spigotted prior to discharge.

- The patient goes home with a catheter for TWOC* at 2 days by either the Day Ward or district nurse / catheter specialist nurse.

Peri-operative Analgesia

- No pre-operative analgesia

- Intra-operative fentanyl and IV paracetamol.

- Postoperative regular paracetamol with codeine if needed.

- Problems managing post-operative pain are uncommon after bipolar surgery.

Take Home Medication

- Paracetamol and codeine as required for 3 days

- No post-operative antibiotics unless concern for infection then oral ciproxfloxacin 500mg bd for 5 days

*TWOC = Trial WithOut Catheter

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/44739/hidi-lloyd-_prost-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse7

Elizabeth Reynolds* Foundation Year 2 Doctor, Wythenshawe Hospital

Carol Makin Consultant General Surgeon, The Medical Specialist Group, Guernsey

The Medical Specialist Group and Princess Elizabeth Hospital, Guernsey

Corresponding author:ecreynolds@doctors.org.uk

Key Words Day surgery, post-operative analgesia

Abstract

Introduction We investigated the process of patients acquiring analgesia following day surgery carried out in our local hospital.

Methods Interviews were conducted with patients and staff who receive, prescribe, and dispense analgesia following day surgery.

Results Surgeons: Frequently employ local anaesthetic intra-operatively. They do not routinely prescribe discharge analgesia.

Anaesthetists: Prescribe analgesia routinely - paracetamol, ibuprofen, and codeine. They are concerned patients cannot be relied on to purchase their own supplies.

Day Ward Nurses: Label and dispense all drugs ordered by anaesthetists.

Pharmacists: Supply pre-packed analgesia to the day unit.

Patients: Paracetamol and ibuprofen are commonly taken, codeine rarely. Most are familiar with these analgesics and have supplies at home. They would purchase drugs if instructed.

Conclusions

If patients acquired their own post-operative analgesia

- Dispensing excess quantities of analgesics, particularly codeine, would be avoided

- Staff would have more time to concentrate on direct patient care

- There would be financial savings

Introduction

In the island of Guernsey’s unique healthcare system adult day surgery patients are routinely supplied with take home analgesia. In-patients and paediatric day surgery patients are expected to purchase their own simple analgesia and a take home prescription is only issued for those drugs not obtainable over the counter.

Paracetamol and ibuprofen are the usual analgesics advised which many patients already have at home and are familiar with their use.

This study was designed to ask the question “Why don’t we ask day patients to supply their own post-operative analgesia?”.

Background

The Bailiwick of Guernsey (population 63,000) is a group of islands lying 70 miles from the south coast of England. Healthcare provision is not part of the NHS but broadly follows UK practices. A brief overview is provided in Reference 1. Visits to GPs and emergency department attendances, unless within 48 hours of discharge from hospital, incur a fee.

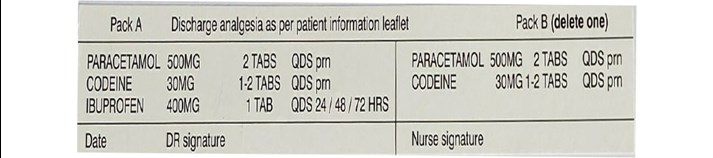

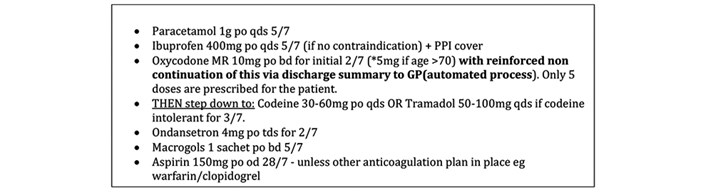

For adults undergoing a day surgical procedure, anaesthetists issue a prescription for take home drugs facilitated by a pre-printed sticker (see Figure1). Drugs are pre-packaged on purchase by the hospital, labelled and distributed by pharmacy, and dispensed by day unit registered nurses. Depending which prescription is signed the following quantities are dispensed: Paracetamol 16 x 500mg, Ibuprofen 24 x 400mg, Codeine 28 x 30mg. Patients do not pay for the medication.

Figure 1 Pre-printed analgesic prescription sticker.

Method

One author, ER, carried out structured interviews with all staff involved in prescribing and dispensing medication to day-case patients.

Patients were invited to complete an anonymous questionnaire featuring the following 6 questions.

- Has pain relief after your operation been discussed with you before coming to the Day Patient Unit?

- Do you usually have paracetamol or ibuprofen at home?

- If you had been asked, would you have been willing to purchase your own simple pain relief (paracetamol and ibuprofen) or use any you have at home?

- Did you expect to take pain relief home with you after your procedure?

- Do you have any concerns about managing any pain you may have after your procedure?

- Please add any further comments or questions in the space below

The questionnaires were handed out over the space of a week to all patients undergoing day surgery under a general anaesthetic.

An evaluation of cost was also performed.

Results

Surgeons

The surgical team commonly employed local anaesthetic in day-case procedures to aid immediate post-operative pain relief. All other analgesia was managed by anaesthetists.

Anaesthetists

The pre-packaged sets of paracetamol, ibuprofen, and codeine in those without contraindicating comorbidities were prescribed routinely by the anaesthetists as part of their peri-operative pain management strategy. There was reluctance from the anaesthetic department to change current practices for several reasons. Historically standardisation of post-operative analgesia had been introduced as a measure to reduce urgent presentations to the Emergency Department with post-operative pain. Prior to 2018 this would have incurred a fee for the patient as well as potentially creating work for the duty surgeon. Anaesthetists expressed concerns that patients could not be relied upon to provide for and comply with a self-administered medication regime. As Guernsey charges for primary care and has no 24-hour pharmacy facilities, access to analgesia was a factor they thought worth consideration.

Overall, anaesthetists felt that it was their responsibility to ensure all patients had access to necessary analgesia, and the easiest way to do this was to adhere to the existing standardised system.

Day Ward Nurses

Registered nurses on the day unit facilitated discharges according to agreed protocols. They were responsible for perioperative patient care including pain management. They labelled and dispensed all take-home medication.

Although dispensing the medication was not particularly laborious, they reported that if ward supplies ran out then a qualified member of staff had to go to pharmacy for each individual patient which was disruptive to their duties and time-consuming.

Other concerns raised by the nursing staff included discrepancies in the different patient information leaflets provided, including instructions on amounts and dosing intervals of postoperative analgesia. Additionally, they thought that codeine prescribing should be more selective. Many patients who were contacted by the day unit nurses by telephone routinely the day after operations, such as laparoscopic cholecystectomies, reported they could manage their pain without opioids and those who did use them often had side effects. Nurses expressed concerns that codeine had the potential be abused or passed on to others, something they had anecdotal experience of.

Generally, day unit nurses believed patients could manage their own postoperative analgesia.

Pharmacists

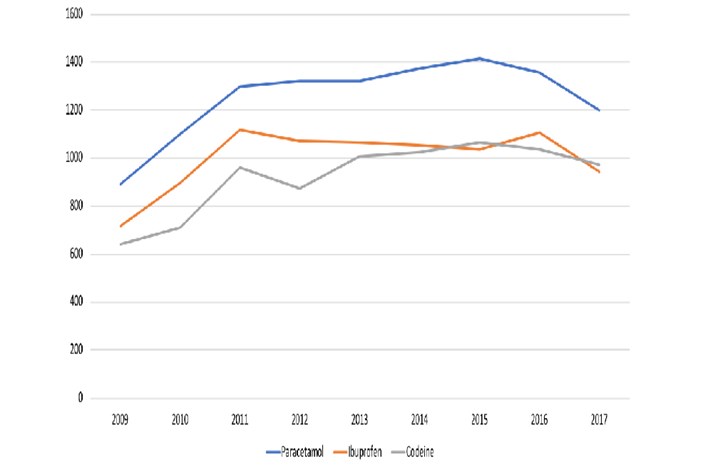

The hospital pharmacy supplied the day unit with analgesia on a weekly basis. Quantities of analgesics issued each year from 2009 to 2017 can be seen in Figure 2. Pharmacists raised important issues surrounding the amount of medication being wasted, as well as the over-prescription of codeine which could only be sourced in packs of 28 tablets. They supported the idea of streamlining the process and aiming to reduce waste.

Although the medications themselves cost the hospital pharmacy the same as patients would pay for over the counter medication, the hospital then faces additional costs to package and label these medications as well as the cost of delivering them to the ward.#

Figure 2 Number of packs of paracetamol, ibuprofen and codeine dispensed each year between 2009 and 2017.

Patients

The results of patient questionnaires showed that 7 of 8 patients who responded had both paracetamol and ibuprofen at home. The same number of patients said that, if asked, they would be happy to purchase or use their own simple analgesia, with the 1 other patient saying they would consider doing so.

Only 50% of patients had expected to take home analgesia after their surgery, and no patients had any concerns about managing their pain at home.

All patients were given packs of analgesia, even if they informed the staff that they were happy to use what they had at home.

Discussion

Patients are being encouraged to take more responsibility and actively participate in their care. Examples include enhanced recovery following surgery and the get-well dressed campaign which both aim to promote a more rapid recovery, earlier discharge from hospital and quicker return to normality.

Day surgery is advocated whenever possible, as it associated with a reduction in several important risks such as hospital acquired infections and thromboembolic events. Patients are mobile faster and can return more readily to their normal lives (2). Post-operative pain management is an essential part of post-operative care aiming to ensure comfort and thereby facilitating early restoration to normal activity.

BADS (British Association of Day Surgery) guidelines (2) state that patients may be encouraged to buy their own simple analgesia, and the most important thing is that all patients should be discharged with appropriate written and verbal instructions on analgesic use. Additionally, this should include post discharge support information about signs and symptoms to expect potential complications and in the event of concerns who to contact. Advice following most procedures is to take analgesia regularly for a minimum of 3 days following day surgery (3)

Paracetamol is the analgesic advised to be taken routinely following day surgery, supplemented by ibuprofen and/or codeine. In the packs issued, if all drugs were taken regularly as advised, our patients received 2 days’ supply of paracetamol, 8 days of ibuprofen and depending on dose 7 or 3.5 days of codeine. Most patients would need to purchase extra supplies of paracetamol during their recovery.

Codeine although regularly dispensed was rarely used. Looking at the pharmacy data it appears that codeine is prescribed in similar quantities to ibuprofen. This is probably in due to the way the prescription sticker is written (Figure 1). Given the potential for exacerbating nausea and vomiting, the constipating effect and misuse there seems to be no advantage to issue this routinely.

Our small study confirmed that patients are familiar with the common analgesics usually advised and often have supplies already at home. By diverting the onus of sourcing simple post-operative analgesia onto patients and carers, pharmacists, nursing, and medical staff would have time released for direct patient care.

The cost of supplying day unit post-operative take-home analgesic drugs in our hospital was approximately £2000 in 2016. However, this does not consider factors such as time taken by pharmacists and nurses to prepare, label, and dispense the medication. Whilst savings would be relatively modest in our small unit serving a population of 63,000 where the day surgery rate is below the average for England & Wales, extrapolation to a hospital serving a population of 500,000 would release in the order of £20k.

This study has demonstrated a potential for better use of resources creating a win: win: win situation for patients, medical, pharmacy and nursing staff, and hospital management. In order to change the current situation it requires day surgery patients to be informed in plain English what arrangements they need to make for post-operative analgesia – which analgesics to ensure they have at home, how to take them and when, the potential adverse effects, and who to contact if they have a problem. Prior to discharge they need to be asked if they do have supplies at home and if not, a limited pack dispensed at registered nurse discretion.

We end with the opening question:

“Why don’t we ask day patients to supply their own post-operative analgesia?”

Figure 1 Pre-printed analgesic prescription sticker.

Figure 2.

References

- Locate Guernsey [cited 2019 May 28] https://www.locateguernsey.com/your-home/health-in-guernsey/

- I Smith, D McWhinnie, I Jackson ED, editors. Day Case Surgery. Oxford University Press; 2012. p.135

- L Tharakan & P Faber. Pain management in day-case surgery. BJA Education 2015; volume 15, issue 4, p180-183. vailable from: https://doi.org/10.1093/bjaceaccp/mku034

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/43852/304-reynolds.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse8

Mr Michael Kent MBBS, BSc, MSc (Tr Surg), FRCS (Tr&Orth), Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon 1

Dr Claire Blandford MBBS FRCA EDRA PGCertMedEd, Consultant Anaesthetist 1

Dr Anne-Marie Bougeard MA (Oxon), MBBS, MRCP, FRCA, Specialty Trainee 7, Anaesthesia 2

Dr Mary Stocker MA (Oxon), MBChB, FRCA, Consultant Anaesthetist 1

Contributors

Mrs. Bernice Sullivan, Senior Physiotherapist 1

Mrs. Alex Alen, Senior Day Surgery Nurse 1

Mrs. Jo Allen, Outreach Team Leader 1

Authors' addresses

- Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Lowes Bridge, Torquay, Devon, TQ2 7AA, UK

- University Hospitals Plymouth NHS Trust, Derriford Road, Plymouth, Devon, PL6 8DH, UK

Key words Ambulatory surgery, Day Case Hip Replacement, Day Case Arthroplasty

Abstract

Introduction Outpatient total hip arthroplasty (THA) is commonplace in the United States (US) offering advantages for patients and healthcare providers. We hypothesised that it would be possible to perform day case THA in the NHS. There are limited reports of this in the United Kingdom (UK).

Method We report our experience of implementing a pathway to allow safe day of surgery discharge following THA. Data were prospectively collected on 32 patients between September 2018 and January 2020.

Results 30 patients (94%) were discharged home on the same day. Dizziness and postural hypotension associated with deviation from our anaesthetic and analgesia protocol were the only reasons for the 2 failed discharges. The median time to discharge was 9hrs 34mins (interquartile range 9hrs 19mins – 11hrs 31mins [total range 8hrs 30mins – 12hrs 2mins]). Both unplanned admissions were discharged the day after surgery. Post discharge data was available in all patients: 22 (74%) reported no or mild pain; 8 (26%) reported moderate pain. There were no readmissions. All patients had high levels of satisfaction. 4 patients had staged consecutive day case THAs. ‘Second side’ patients much preferred the day case pathway compared with previous inpatient stays.

Conclusion We found that patients can be safely discharged on the day of surgery after THA, with high levels of satisfaction. We had a very low failed discharge rate (6%) compared with the published literature. Expectation management, patient education, consistent messaging and highly protocolised treatments were vital factors. This clearly offers improved management of resources and financial savings to healthcare trusts.

Introduction

Most NHS hospitals in the UK face daily challenges to inpatient capacity, placing significant pressure on elective surgery waiting lists resulting in ever increasing delays for patients awaiting surgery. Lower limb arthroplasty is particularly vulnerable to cancellation, as priority is given to urgent and cancer surgery when there are capacity pressures. In the winter of 2017-18 a temporary amnesty was placed on elective orthopaedic operating by NHS England in order to free up beds for non-elective admissions [1].

Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) protocols are well established in orthopaedic practice in the UK [2-4]. They are designed to attenuate the surgical stress response, allow patients earlier return to normal function and reduce complication rates [5]. Units with strong adherence to ERAS principles have lower lengths of stay and readmissions and are able to provide high quality treatment with a lower demand on precious inpatient resources [2,4].

In the US and Scandinavia, lower limb arthroplasty surgery with discharge on the day of surgery is a well-established, safe practice [6-12]. In 2011, our hospital commenced a day case pathway for unicondylar knee arthroplasty (UKA), and 70% of our patients now undergo this operation as a day case [13,14]. This is popular among patients, offering excellent clinical outcomes, and low complications and readmissions.

Our unit has a well established ERAS model which includes: standardised preassessment and optimisation of existing co-morbidities, an extensive preoperative patient education programme (including comprehensive booklets, videos and ‘Joint School’ group sessions run by surgeons, physiotherapists and nurses) and a well-established orthopaedic outreach team who provide post-discharge care for all arthroplasty patients in their homes after surgery.

We hypothesised that it would be possible to replicate the success of our UKA practice and undertake total hip arthroplasty (THA) with discharge home on the day of surgery, and designed a pilot study protocol to assess safety and feasibility [13-15]. There are limited reports of outpatient THA in the United Kingdom. We present our experience of implementing this pathway in a medium sized district general hospital.

Patients and Methods

Background work

Using quality improvement methodology, treatment interventions within the first 24hours of the inpatient pathway were assessed: time to mobilisation, frequency of urinary catheterisation, incidence of significant postoperative nausea and vomiting, and requirements for rescue analgesia.

Similarly, anaesthetic/analgesic techniques, physiotherapy protocols and follow up arrangements with the outreach team were assessed and refined to create a robust pathway for day case THA patients.

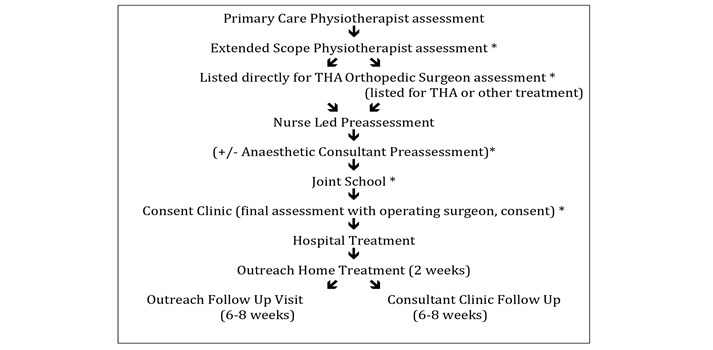

Additionally, we established points in the referral pathway (from primary care referral to consultant outpatient clinic assessment), where suitable patients could be identified and consideration was given to how patients could be appropriately counselled and recruited to consider a day case THA (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – Patient treatment pathway * opportunities to discuss day case surgery with patient.

Patient selection

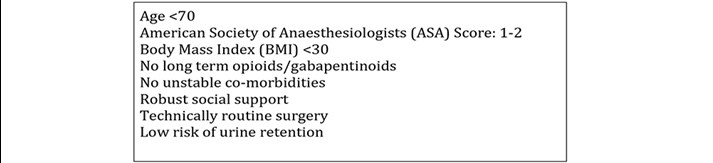

Patients with symptomatically intrusive hip pathology, who had failed conservative treatment, requiring a THA, were considered.

We identified criteria for patient selection for the pilot study, selecting conservative criteria for the initial phase (Figure 2). As our experience developed, we began to relax some of these criteria to include some ASA3 patients and one, very motivated patient who was pre-operatively taking opioid & gabapentinoid medication.

Figure 2. Inclusion criteria.

In accordance with national day surgery guidance [16] we ensured that all patients on this pathway were booked as intended day cases. This is essential for three reasons:

- National reporting for day surgery relies on the documented intended management as a day case and a length of stay of zero days.

- Setting patient expectations is key to the success of day surgery pathways. If the patient is booked as a day case they will receive consistent messaging from all members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT). More importantly the patient and their carer are clear about their intended pathway and can prepare appropriately for same day discharge.

- In times of hospital escalation when bed capacity is limited, patients who are scheduled for inpatient surgery have a much higher risk of cancellation (even if they may in fact have been able to be discharged as day cases). Ensuring that patients are scheduled as day cases, not requiring of any inpatient resource, decreases their risk of cancellation.

Anaesthetic technique

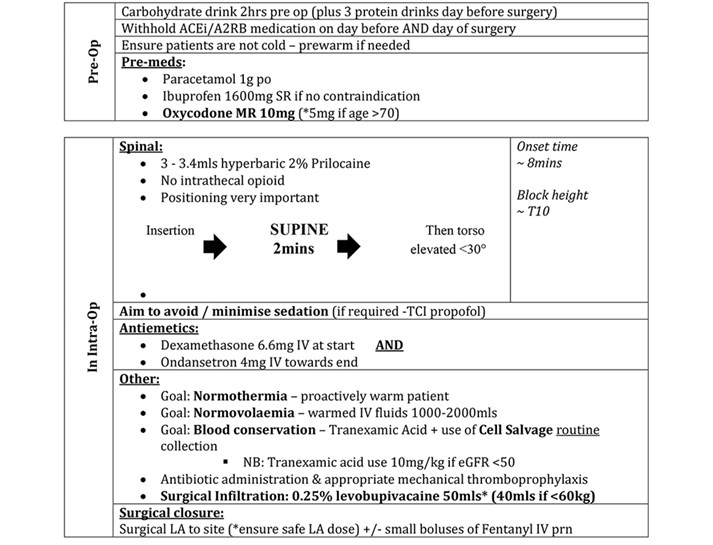

We analysed our previous year’s postoperative pain scores and correlated these with the anaesthetic technique used. In addition, we reviewed published ambulatory protocols [6-9,17,18] to design our anaesthetic technique as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Anaesthetic/perioperative protocol.

Surgical technique

Between September 2018 and January 2020, 32 patients were selected to have their THA as a day case. All patients received a standard THA, performed by or under the direct supervision of five consultant hip arthroplasty surgeons (MK, MA, GH, SP, AA), Several different THA implant systems were used: Exeter cemented stems, Trident acetabular systems (Stryker, Mahwah, New Jersey), Corail uncemented stems and Pinnacle uncemented acetabular systems (DePuy Synthes, Warsaw, Indiana). It is important to emphasise that there was no deviation from the surgeon’s standard approach or technique.

After implantation of the femoral components, all patients received infiltration of 40-50mls 0.25% Levobupivacaine local anaesthetic into the surgical field (joint capsule, muscle, fascia lata, subcutaneous tissues and skin) using a 22 gauge needle. Routine cell salvage collection was performed whenever possible with blood being processed and re-transfused if sufficient volumes were obtained. This strategy was introduced as a cost neutral intervention in place of routinely performing a second group and save sample on the day of surgery. Our trust was an early adopter of cell salvage so we were fortunate to have sufficient processing machines available to introduce this change. Processing was performed if there was deemed to be sufficient volume required for the device (minimum 55mls concentrated red cell volume), this threshold was reached in 65% of our cohorts’ patients.

No surgical drains were used. Transosseous muscle repair was undertaken in all cases using drill holes and Ethibond sutures. Multi-layered surgical closure was undertaken with deep absorbable Vicryl sutures, subcutaneous absorbable Monocryl sutures and additional surgical clips in selected cases. Wound glue and an adherent water-resistant dressing were applied in all cases.

Our hospital has a stand-alone dedicated day surgery unit (DSU) connected to the main hospital site via an internal corridor. The majority of day surgery is undertaken within this unit, which is staffed by a dedicated day surgery team. However, there are no laminar flow theatres within DSU so these THAs were performed in the main orthopaedic theatres. Where possible, all cases were planned as the first morning case on the operating list. Post-operatively, patients spent a short time in primary recovery before being transferred to the DSU for secondary recovery and discharge. A small number of patients underwent surgery at the weekend when the DSU was closed. These patients were managed postoperatively on the inpatient orthopaedic ward.

Venous Thromboembolism Prophylaxis

All patients received mechanical prophylaxis whilst in hospital and a prophylactic dose of 5000iU of Dalteparin 6 hours after administration of their spinal anaesthetic. Patients who were not on oral anticoagulation then received 150mg of Aspirin once a day for 28 days. Patients on anticoagulation restarted this on the day after surgery and where required, dose monitoring was undertaken by the outreach team.

Mobilisation and discharge process

All non-diabetic patients were given an energy drink in their initial recovery stage (Fresubin energy 200mls or similar), with an aim to reduce any first mobilisation dizziness and enhance feelings of wellbeing. They were then encouraged to eat and drink as normal and were given regular analgesia with additional top ups as required (see analgesia section). As soon as the spinal anaesthetic had worn off and they felt able to do so, patients were mobilised by physiotherapists, full weight bearing with crutches, applying no hip precautions.

Standard discharge criteria included: transfer from supine to a standing position; walk >30 metres without assistance and ascend and descend a flight of stairs. They were given an information booklet and enrolled in routine outpatient physiotherapy. All patients had a radiograph undertaken prior to discharge, which was reviewed by the operating surgeon.

On discharge, patients were provided with a standardised medication package and checklist with timings, drug descriptions and instructions (Figure 4). Pain and nausea scores were recorded at the point of discharge. Patients were given a 24-hour emergency contact number for the day surgery nursing team during working hours or a senior orthopaedic nurse out of hours.

Figure 4 Discharge medication.

All patients were visited at home on the morning after surgery by the orthopaedic outreach team where symptoms and progress were assessed, observations and blood tests were taken, and medication advice was given. Had urethral catheterisation been required then outreach managed the removal process.

The outreach team visited the patients at home again on days 3, 7, 10, providing wound care and support. Any issues were fed back directly to the operating surgeon. It is important to note that whilst the outreach team provided vital support to our day case pathway, this is a longstanding established role for all arthroplasty patients, not a new service implemented for this pilot.

Additionally, all patients were telephoned at 24 hours by the DSU team to record pain scores, nausea or vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness and at 7 days satisfaction with the process was recorded. Pain levels were assessed using a Verbal Rating Scale, satisfaction using a simple descriptive scoring system.

Patients were reviewed at six weeks post operatively by the operating surgeon.

Results

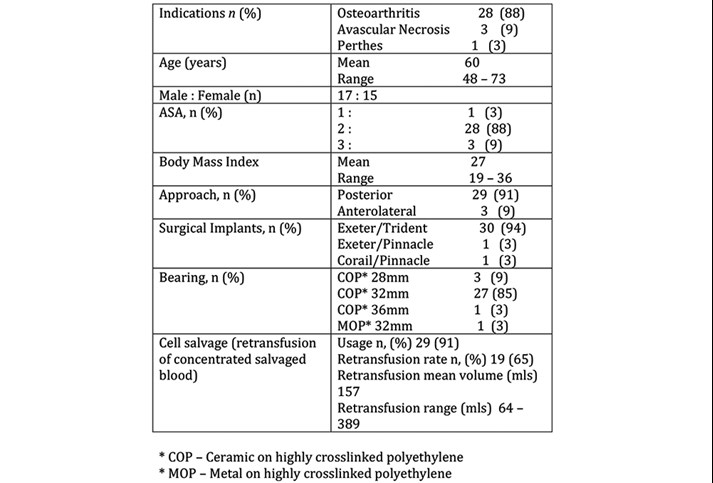

Table 1 shows the indications for surgery, patient demographics, implant and cell saver usage. Most patients received a hybrid THA with a 32mm ceramic on highly crosslinked polyethylene bearing via a posterior approach. The majority of patients were ASA-2, with a mean age of 60 years and a BMI of 27. 65% of patients received an autotransfusion, with a mean re-transfused volume of 157mls.

Table 1 Patient demographics/Intraoperative data.

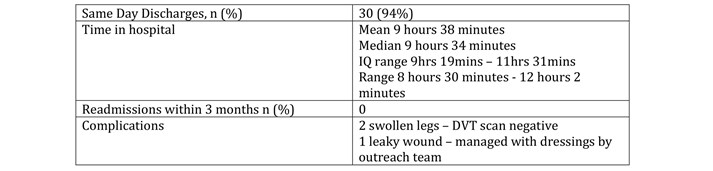

Table 2 shows that of the 32 planned day case THA patients, 30 (94%) were successfully discharged on the day of surgery. No patients were readmitted within a three-month period. There were no significant complications (dislocations/infections/VTE). Two patients had moderately swollen operative limbs but had negative DVT scans. One patient had a leaky wound 10 days postoperatively, that was managed successfully with dressings by the outreach team.

Table 2 Discharge/Complication data.

The two patients (6%) who could not be discharged both had significant dizziness due to postural hypotension which precluded them completing physiotherapy discharge goals on the day of surgery. For these patients, Day 0 pain scores were 1/10 and 2/10 and they reported no nausea. Both were successfully discharged on the morning after surgery and had undergone a posterior approach THA. Of interest, in both of these cases there was deviation from the protocol. Due to timing concerns the patients had received a 0.5% levobupivaciane spinal, which is longer acting than Prilocaine both in terms of motor block and haemodynamic effect. Other deviations included failure to appropriately omit pre operative ACE inhibitor medication (1), non administration of post operative energy drink (1) and non standard timing of analgesia(1). There was one patient where deviation from protocol did not result in failed discharge however, where the protocol was followed, 29/29 patients successfully discharged on their day of surgery.

25 patients (78%) were discharged through the DSU. Seven patients (22%) were managed through the inpatient orthopaedic ward (due to the fact that the DSU was not open at the weekend). Both unplanned admissions were initially managed through the DSU and admitted overnight to the inpatient ward.

31 patients (97%) were operated on as the first case of the morning session. One patient was operated on later in the day (with a start time of 1215) but was successfully discharged on the day of surgery, from the inpatient ward.

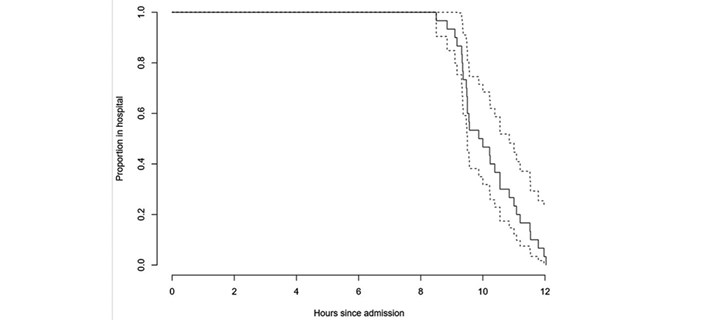

Seven patients were ‘second sides’ having had a previous THA through an inpatient pathway. Six of these patients were discharged on the day of surgery. Four patients had staged consecutive THAs done as a day case and were all successfully discharged on the day of surgery. The median time to discharge was 9hrs 34mins (interquartile range 9hrs 19mins – 11hrs 31mins [total range 8hrs 30mins – 12hrs 2mins]). Time to discharge is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 Patient demographics/Intraoperative data.

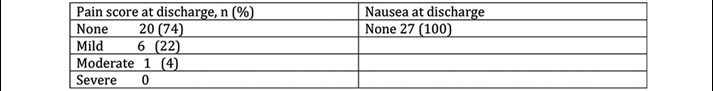

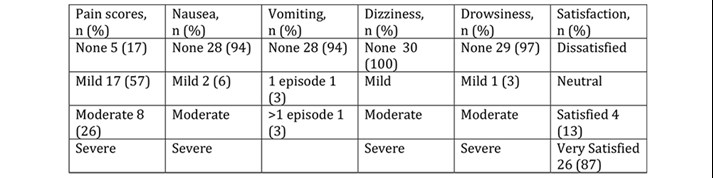

Discharge pain and nausea scores were collected for 27/30 patients discharged on the day. Table 3 shows that 96% of patients had no or mild pain and no patients had nausea at the point of discharge. Table 4 shows that at 24 hours, 74% of patients had no or mild pain, 26% moderate and no patient reported severe pain. There were very low levels of day 1 nausea and vomiting (94% of patients reported no symptoms). No patients reported dizziness and drowsiness was very rare (3%). All patients were either very satisfied (87%) or satisfied (13%) with day case THA, no patient reported dissatisfaction with this process.

Table 3 Anaesthetic/perioperative protocol.

Table 4 Outcome scores at 24 hours, satisfaction at 7 days.

There was no difference in time to discharge on the day of surgery or pain scores at discharge comparing posterior approach patients and anterlolateral approach patients. All three anterolateral approach patients reported ‘moderate’ pain at 24hours, whereas 80% of posterior approach patients reported ‘no’ or ‘mild’ pain at 24 hours. In our cohort, ASA grade did not appear to be an independent factor in determining successful day case discharge, indeed our three ASA3 patients were successful day cases, as were the two technically complex cases.

One patient had an asymptomatic postoperative haemoglobin of 90g/dl. She was the only patient with a postoperative level of less than 100g/dl. There were no other abnormalities comparing postoperative blood tests with baseline.

Discussion

This pilot study has demonstrated that day case THA in the NHS is feasible, safe and acceptable to patients.

We have achieved a 94% successful discharge rate with no readmissions or complications. Our unplanned admission rate of 6% is extremely low and compares very favourably with rates of up to 60% reported by some units [6, 10, 11]. Indeed, all four patients who required a further THA following a successful previous day case THA opted to follow the day case pathway again for their second side. Similarly, all seven of the patients who had undergone a previous inpatient THA stated that they far preferred the day case pathway, as it offered an equivalent or better standard of care in the comfort of their own home, with accelerated rehabilitation and recovery.

The success of this pilot to date is multifactorial. It is well documented that units with strong adherence to protocolised ERAS pathways are more likely to achieve consistent outcomes [2-4, 9-11]. Our hospital is in a strong position to be able to provide day case pathways for lower limb arthroplasty. We have a well established, successful day surgery unit co-located on site, extensive experience of undertaking major orthopaedic and general surgery as a day case, a robust enhanced recovery programme and a specialist orthopaedic outreach team to visit patients postoperatively in their own home.

In our opinion, patient selection, engagement with the day case pathway and achieving consistent messaging from staff are key determinants of a successful outcome. We believe that introducing the concept of day case early in the patient’s referral pathway is vital to set expectations and ensure confidence in the pathway through education. Patients who are medically and socially suitable for a day case procedure are then primed to expect to mobilise early and return home on the day of surgery.

Adherence to ERAS principles is vital to success [4]. Physiologically, patients should be optimised prior to surgery, undergo anaemia management, and have perioperative warming to normothermia. We prescribe carbohydrate loading drinks in addition to free clear fluids to the point of sending for theatre. Highly protocolised anaesthetic and analgesic regimes are crucial. Patients are premedicated with long acting analgesia, and are given no or very minimal sedation to encourage early diet and ambulation. Our anaesthetic is a short acting spinal anaesthetic, with minimal haemodynamic disturbance, careful attention to fluid balance and blood loss, with replacement through cell salvage where possible, and high volume local anaesthetic infiltration by the surgeon to all cut surfaces. Importantly, surgical techniques must be consistent and remain unchanged from standard practice. Surgical approach didn’t appear to have any affect on the rate of discharge, or the time spent in hospital, but anterolateral approach patients reported slightly higher postoperative pain scores.

We initially used Pregabalin as part of our day case pain protocol as this aligned with our inpatient practice. However, we noted an excess of reported dizziness in the inpatient cohort so withdrew the usage of it from both protocols in December 2018. We have found there to be no additional benefit from the drug and indeed there has been no detrimental effect on pain scores since its withdrawal. During this study we also redefined our post-operative chemical thromboprophylaxis to include Day 1 & 2 postoperative Dalteparin doses as discharge medications to be subsequently followed by 28 days of 150mg Aspirin daily.

As an organisation, day case arthroplasty is very attractive. We have conducted a brief health economics analysis of our results. An overnight stay in our hospital costs £288. Our current average length of stay for low risk patients is 3 days. The day case pathway incurs an extra two orthopaedic outreach visits (which cost £25 per visit), representing a post operative care saving of £814 per patient.

Our initial inclusion criteria were quite strict. These widened as our confidence in the pathway grew, to include older, more unfit, larger patients requiring technically more demanding surgery. It appeared that expectation setting, patient engagement, motivation and belief in the process were perhaps more important factors than BMI and ASA grade in predicting discharge and outcome.

We have analysed the THA patients on our waiting list and anticipate that approximately 20% patients would be suitable for a day case procedure. Our hospital carries out around 300 THAs a year. If 20% of these patients were to undergo day case procedures this would improve waiting times by reducing cancellations due to lack of inpatient capacity, and make a potential saving of £48,840.

We are looking at ways of working to incorporate an overnight stay option for patients who for organisational reasons cannot go first on the list but would otherwise be suitable for day case and may be discharged early on day 1 postoperatively. One of the barriers to discharge identified was the availability of staff (our physiotherapists finish their day at 1600hrs) to mobilise patients, therefore this could be addressed by up-skilling other staff and we are currently evaluating a competency package to enable our day surgery team to undertake aspects of this role.

We have applied the learning points from this pilot to optimise our inpatient and planned trauma pathways, utilising the day case THA anaesthetic/analgesia protocol for all hip and knee patients. The ‘day case effect’ has also brought about a culture change within the unit, by demonstrating the benefits, feasibility and safety of short stay treatment both to staff and patients, we have improved length of stay and outcomes for all elective and trauma patients.

There are limitations to this study. This is a small pilot study in a highly selected group of patients, who do not represent the majority of the patients on our waiting list. We have a multi-morbid elderly population, and a wide, rural, geographical catchment, which means that for many patients a day case arthroplasty procedure is not suitable. However, based on the initial success of the pilot we are now widening the inclusion criteria for day case THA and developing a day case pathway for Total Knee Arthroplasty patients.

Conclusion

It is safe, feasible and acceptable to patients to offer total hip arthroplasty as a day case. This satisfies all the aspirations of an enhanced recovery programme and has the potential to improve outcomes for all orthopaedic patients in our institution. Expectation setting, patient education and adherence to a robust protocol were key factors.

References

- The Telegraph 2017. NHS Hospitals ordered to cancel all routine operations in January as flu spike and bed shortages lead to A&E crisis. Available from: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2018/01/02/nhs-hospitals-ordered-cancel-routine-operations-january/

- Soffin EM, YaDeau JT. Enhanced recovery after surgery for primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a review of the evidence. BJA 2016;117:iii62-72

- Zhou S, Qian W, Jiang C, Ye C, Chen X. Enhanced recovery after surgery for hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Postgrad Med J 2017;93:736-42

- Wainwright TW, Gill M, McDonald DA, Middleton RG, Reed M, Sahota O, Yates P, Ljungqvist O. Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations. Acta Orthop. 2020 Feb;91(1):3-19.

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to control postoperative pathophysiology and rehabilitation. BJA 1997;78(5):606-17

- Larsen JR, Skovgaard B, Pryno T, Bendikas L, Mikkelsen LR, Laursen M et al. Feasibility of day-case total hip arthoplasty: a single-centre observational study. Hip Int 2017;27(1): 60-5

- Brerend JR, Lombardi AV Jr, Brerend ME, Adams JB, Morris MJ. The outpatient total hip arthroplasty: a paradigm change. Bone Joint J 2018;100-B:31-5

- Pollock M, Somerville L, Firth A, Lanting B. Outpatient total hip arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: a systematic review of the literature. JBJS Rev 2016;4:12

- Li J, Rubin LE, Mariano ER. Essential elements of an outpatient total joint replacement programme. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2019 Oct;32(5):643-648.

- Sershon RA, McDonald JF 3rd, Ho H, Goyal N, Hamilton WG. Outpatient Total Hip Arthroplasty Performed at an Ambulatory Surgery Center vs Hospital Outpatient Setting: Complications, Revisions, and Readmissions. J Arthroplasty. 2019 Dec;34(12):2861-2865.

- Husted C, Gromov K, Hansen HK, Troelsen A, Kristensen BB, Husted H. Outpatient total hip or knee arthroplasty in ambulatory surgery center versus arthroplasty ward: a randomized controlled trial. Acta Orthop. 2020 Feb;91(1):42-47.

- Lazic S, Broughton O, Kellet CF, Kader DF, Villet L, Rivière C. Day case surgery for total hip and knee replacement. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3(4). Doi:

- Bradley B, Griffith S, Stocker M, Hockings M, Isaac D. Unicompartmental Knee Replacement as Day Case Surgery: A Pilot Study. The Journal of One Day Surgery 2014;24:16–18

- Bradley B, Middleton S, Davis N, Williams M, Stocker M, Isaac DL. Discharge on the day of surgery following unicompartmental knee arthroplasty within the United Kingdom NHS. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B(6):788-92

- Churchill L, Pollock M, Lebedeva Y, Pasic N, Bryant D, Howard J, Lanting B, Laliberte Rudman D. Optimizing outpatient total hip arthroplasty: perspectives of key stakeholders. Can J Surg. 2018 Dec 1;61(6):370-376.

- British Association of Day Surgery. Directory of Procedures 6th Edition. London.

- Manassero A, Fanelli A. Prilocaine hydrochloride 2% hyperbaric solution for intrathecal injection: a clinical review. Loc Reg Anesth 2017;10:15-24

- Amundson AW1, Panchamia JK, Jacob AK. Anesthesia for Same-Day Total Joint Replacement. Anesthesiol Clin. 2019 Jun;37(2):251-264

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/43853/304-kent.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse9

Anna Fergusson Specialty Trainee in Anaesthetics1

Andrew Weir Specialty Trainee in Anaesthetics1

Rowan Mankiewitz Trust Doctor1

Subramanian Narayanan Consultant Gynaecologist2

Jonathon Hindley Consultant Gynaecologist2

Eleanor Rayner Specialist Registrar in Obstetrics and Gynaecology2

Mary Stocker Consultant Anaesthetist1

Authors' Addresses

1Department of Anaesthetics, Torbay Hospital

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Torbay Hospital

Keywords: Day Surgery, Hysterectomy, Gynaecology

Abstract

Introduction: Hysterectomies are common procedures which traditionally have been performed via an inpatient pathway. However, there is evidence that day case surgery is safe, has a high level of patient satisfaction, and provides a cost-effective, bed-saving service. This audit reviews patient outcomes and satisfaction following day case hysterectomy.

Method: The data for a 5-year period for all patients undergoing laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomy were reviewed. Patient outcomes including unplanned admissions, reasons for admission, complications at day 1 for discharged patients and patient satisfaction were collected.

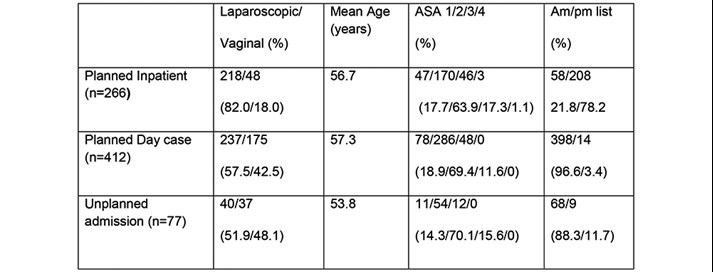

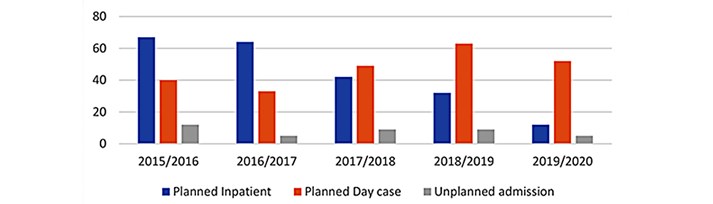

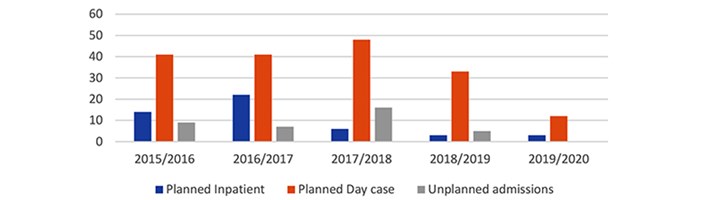

Results: During the 5-year period 678 laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies were performed of which 60.8% were via a day case pathway; of these 57.5% were laparoscopic and 42.5% vaginal. Of the day case group, 77 required admission (18.7%). Since the introduction of the day case hysterectomy service, the planned day case rate has increased from 37.4% to 81.3% for laparoscopic hysterectomies, and from 74.6% to 80% for vaginal hysterectomies. During this time unplanned admissions rates have reduced, demonstrating an improvement with confidence and experience.

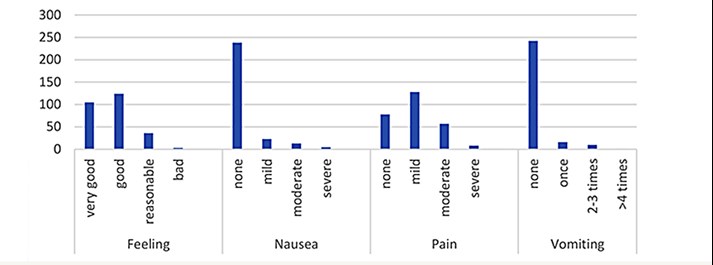

The commonest reason for admission was pain (38.3% of unplanned admissions) followed by surgical complications. Pain was also the commonest complication reported at day 1 amongst those who were discharged; 21% reported moderate pain and 3% reported severe pain. Of those who were discharged, 100% were satisfied or very satisfied with their experience.

Conclusions: This audit demonstrates that both laparoscopic and vaginal day case hysterectomies can be safely performed with an acceptable admission rate, minimal post-op morbidity and good patient satisfaction.

Introduction

Hysterectomies are the most common major gynaecological operation performed worldwide, with almost 35,000 performed in the UK in 2018/20191. Until recently, the vast majority of these have been performed via an inpatient pathway; HES data from 2018/2019 shows that 1.5% of hysterectomies performed in England were day cases1. There is however evidence that day case surgery is safe and has a high level of patient satisfaction for a variety of gynaecological procedures, including laparoscopic2 and vaginal hysterectomy3. Day case surgery is associated with reduced inpatient bed usage and health economic benefits.

The Torbay Hospital Day Surgery Unit is a progressive unit and has experience in performing major procedures as day cases. For the majority of this study period it was open until 8pm, at which point all patients are either discharged or admitted to the main hospital. Recently the unit’s opening hours have been extended to 9pm and we anticipate that this will further increase our successful discharge of complex surgical procedures such as hysterectomies. From 2015, hysterectomies have been preferentially planned and listed as day cases, unless there are convincing surgical, anaesthetic or social contraindications. This review aims to assess the outcomes over this period.

Methods

The data for all patients having a hysterectomy at Torbay Hospital over a 4-year and 8-month period from April 2015 to November 2019 was retrospectively reviewed. For those planned as day cases, data was collected from our Day Surgery Unit computer database, Galaxy Surgery (ÓCSC). This database records multiple aspects of the patient’s pathway, including date of surgery, age, American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status classification grade, timings, surgical procedure(s), anaesthetic technique and discharge or unexpected admission. As is routine at Torbay Day Surgery Unit, those discharged were telephoned the following day by a dedicated team of nursing staff to offer support and advice, trouble shoot any post-operative complications and collect post-discharge follow up data. This data includes information on pain level, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, drowsiness, bleeding and any other complications using multiple choice questions. Patient satisfaction is also collected using a three-point Likert scale (very satisfied, satisfied, not satisfied) and there is an opportunity for the patient to feedback any further information or comments. Where post discharge follow-up data were missing, we examined the patient’s electronic record to identify any admissions or attendances at the Emergency Department (ED) or Surgical Assessment Unit.

For those patients who had an unexpected admission, patient records and discharge summaries were examined to determine the cause of admission. For those on an inpatient pathway, patient demographics and type of surgery were collected for comparison.

Specific anaesthetic technique was not protocolised and was left to the discretion of the anaesthetist. However, anaesthetic techniques within our day surgery unit are all tailored to deliver short-acting anaesthesia, with minimal side effects and multi-modal analgesia. The majority of patients received standard analgesic premedication of paracetamol 1g PO and ibuprofen 1600mg SR PO (if no contraindications were present) and single or dual antiemetic therapy (dexamethasone and/or ondansetron). There are strict protocols in use within our day surgery unit such that long-acting opioids are not available, nitrous oxide is not used and the large majority of patients are anaesthetised using total intravenous anaesthesia. Analgesia is provided both intra-operatively and in the primary recovery unit by use of intravenous fentanyl supplemented with oral morphine as required. Surgery was performed by a number of consultant or senior registrar surgeons, each with their own slightly different surgical and local anaesthetic technique.

Data were analysed using simple descriptive statistics. Where appropriate the Chi-squared test and paired t-test was used to indicate significance.

Results

Table 1.

Figure 1a. Laparoscopic Hysterectomies: Change in Inpatient vs Day case numbers over time.

Figure 1b. Vaginal Hysterectomy: Change in Inpatient vs Day case numbers

over time.

During the 5-year period a total of 678 laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies were performed, of which 412 (60.8%) were via a day case pathway (see Table 1). The proportion of patients who were on a day case pathway increased throughout the 5-year period (see figure 1a and 1b). In 2019/2020, 52/64 (81.3%) of laparoscopic hysterectomy patients and 12/15 (80%) of vaginal hysterectomy patients were planned as day case, compared with 40/107 (37.3%) of laparoscopic and 41/55 (74.5%) of vaginal hysterectomy patients in 2015/2016.

Age was not a factor in determining whether a patient was scheduled for a day case or inpatient pathway. The mean age of patients planned as a day case was 56.7 years vs 57.9 years for the inpatient pathway (p= 0.289). Patients who were ASA 1 or 2 were more likely to be scheduled for a day case pathway compared to an inpatient pathway (p=0.038). There were similar numbers of ASA 3 patients in the day case and inpatient groups (48 vs 46), and all ASA 4 patients were scheduled for an inpatient pathway. These results reflect the policy of our day unit in that patients are not excluded from day surgery due to either age or ASA status.

In the day case group, 237/412 (57.5%) were planned to be performed laparoscopically and 175/412 (42.5%) were planned to be performed vaginally. By comparison, in the inpatient group, 218/266 (82%) were planned to be performed laparoscopically, and 48/266 (18%) vaginally. One hundred and seventy five out of 223 (78.5%) of all vaginal hysterectomies, and 237/456 (52%) of all laparoscopic hysterectomies were planned as day case procedures. One of the factors for a higher number of planned inpatient laparoscopic hysterectomies is that one of our two laparoscopic surgeons has his main operating list scheduled in inpatient theatres in the afternoon. These patients are much less likely to achieve same day discharge so are usually scheduled via an inpatient pathway. It is hoped that in the future more morning operating provision will be available in the day surgery unit to enable these patients to be converted to a day case pathway.

Of the day case group, 77/412 (18.7%) required admission. However, these rates have significantly decreased over time from 25.9% in 2015/2016 to 7.1% in 2019/2020 (p=0.0048). Admission rates were similar in those performed vaginally (37/175, 21.1%) and those performed laparoscopically (40/237, 16.9%, p=0.27). There was a trend but no significant difference between age and unplanned admission rate, with the mean age of 53.8 years in those admitted, compared with 57.3 years in those discharged (p=0.0549). Patient’s ASA grade did not have a significant impact on likelihood of admission. Sixty five out of 364 (17.9%) of ASA 1 and 2 patients required admission compared to 12/48 (25%) of ASA 3 patients (p=0.233). The vast majority of patients were operated on during morning lists; however, of the 14 patients who were operated on during the afternoon, 9 (64.3%) were admitted (p<0.0001).

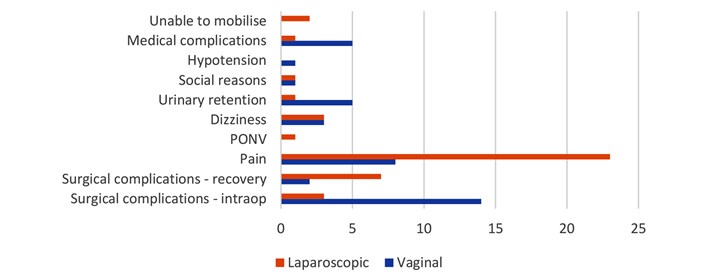

The most common reason for admission was pain (31/77, 40.3% of unplanned admissions). Of these, rates were significantly higher in those having laparoscopic compared to vaginal surgery (23/40, 57.5% vs 8/37, 21.6%, p=0.00134). The second most common reason for unplanned admission was surgical complications (26/77, 33.8% of unplanned admissions). These were split into those which were detected intra-operatively, such as bleeding or conversion to open surgery, and those which were detected in recovery, such as post-operative bleeding. Admission due to intra-operative surgical complications was statistically more common in those having a vaginal hysterectomy, compared to those having a laparoscopic hysterectomy (14/37, 37.8% vs. 3/40, 7.5%, p=0.00134). Other reasons for admission included social reasons, dizziness, urinary retention, inability to mobilise, medical complications, hypotension and post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Reason for admission in those planned as Day cases but required admission.

Post-operative take home analgesia is protocol driven and prescribed for all patients; co-codamol (30/500) 2 tablets 4 times a day plus ibuprofen 400mg 4 times a day if there are no contraindications. Patients are also prescribed Macrogol to avoid post-operative constipation associated with codeine. Day 1 complication rates were generally low, with the majority of patients reporting no or mild pain, nausea, dizziness and drowsiness, none or a little bleeding and none or one episode of vomiting (see Figure 3). Pain was the commonest day 1 complication, with 128/271 (47.2%) having mild pain, 57/271 (21.0%) having moderate pain and 8/271 (3.0%) patients reporting severe pain. Seventy eight out of two hundred and seventy one patients (28.9%) reported having no pain. These results are well within acceptable levels for pain following day case surgery as recommended by the Royal College of Anaesthetists.

Figure 3 Complications at Day 1 amongst those discharged home.

Of those who were discharged and where follow up was available, 100% of patients were satisfied or very satisfied with their experience.

There was no follow up data for 64 (19.1%) of the patients, either because they were not able to be contacted on day 1, or there was a shortage of DSU nursing staff to complete the telephone follow ups. The electronic records were reviewed for these patients to identify any who presented to the ED, surgical assessment unit or were admitted. The majority (56/64, 87.5%) had no further encounters with the hospital in the 7 days following their procedure. Of the 8 patients who re-attended either ED or SAU, 6 were admitted. The cause of the reattendance was bleeding in 4 patients, haematoma development in 2 patients, nausea and vomiting in 1 patient, and urinary retention in 1 patient. No patients reattended due to poorly controlled pain.

Discussion

This review has demonstrated that both laparoscopic and vaginal hysterectomies can be safely performed as day case procedures with minimal post-op morbidity and excellent patient satisfaction. The admission rate was initially relatively high with around 1 in 5 patients requiring admission. This figure is comparable with previous studies. A 2017 systematic review found that of 435 laparoscopic hysterectomy patients from studies that prospectively planned for same day discharge, 78.4% patients were discharged before midnight on the day of their surgery4.

Throughout the past 5 years, increasing numbers are being performed as day case surgery while admission rates appear to be falling. Over the period of the study with increasing confidence and developing expertise of the multidisciplinary day surgery team, these rates have dropped considerably to under 8%. Previous studies of vaginal and laparoscopic hysterectomy have demonstrated a wide range of admission rates, from 4 to 79%5. Unlike the majority of other studies where careful patient selection occurred, listing patients for day case surgery has been the default option for all patients at Torbay since 2015. This occurs regardless of comorbidities and ASA grade, unless an inpatient pathway is specifically selected by the surgeons at booking. This review demonstrated that there was no increase in admission rates amongst those who were ASA 3 compared to ASA 1 or 2. This finding is consistent with advice from the 2019 guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists and the British Association of Day Surgery6, which recommends that ASA grade is not used as a determinant of suitability for day case surgery.

Hysterectomies performed on afternoon lists had a significantly higher rate of admission. Wherever possible, hysterectomies should be performed early in the morning to allow maximum time for discharge, or provisions made to allow later discharges.

Pain was the commonest reason for admission in those planned as day case; this was recorded significantly more frequently amongst those having a laparoscopic hysterectomy compared with a vaginal hysterectomy. Pain protocols utilising a multi-modal approach should be developed and standardised to aim for adequate intra-operative analgesia, and rapid and effective post-operative analgesia.

The second commonest cause for admission was surgical complications. The majority of these were detected in the intra-operative period, allowing the process of admitting the patient to start immediately post operatively. Vaginal hysterectomies were more likely to result in intra-operative surgical complications compared with laparoscopic hysterectomies.

We found that performing hysterectomies as day case surgery is generally well tolerated and associated with a low complication rate. Patient satisfaction amongst those discharged is universally very high.

This audit has a number of limitations. We have only reviewed information which was available within the DSU dataset; this excluded a number of factors likely to influence our results, such as surgical factors (including grade of surgeon and the use of local anaesthetic), and patient factors such as body mass index (BMI), and the presence of acute and chronic pain risk factors. There is likely to be a degree of bias in the data collection of post discharge complications and satisfaction levels; data collected non-anonymously by the care provider is notoriously unreliable. There was a failure to follow up a significant number of discharged patients – it is unclear if these patients will have been representative of patients as a whole or did not engage in the follow up process because of their experience. Patients on the boundaries of health care systems could have presented elsewhere with complications and would therefore not appear on our database, leading to an under-estimation of readmissions.

We believe that these results are representative of the wider population and as such can be extrapolated to similar hospitals and patient groups. Further work could explore specific analgesic protocols for use in laparoscopic hysterectomies, protocols for listing criteria using shared decision making, and formal health economic analysis.

References

- NHS digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity - NHS Digital [Internet]. [cited 2020 May 31]. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/hospital-admitted-patient-care-activity

- Schiavone MB, Herzog TJ, Ananth C V., Wilde ET, Lewin SN, Burke WM, et al. Feasibility and economic impact of same-day discharge for women who undergo laparoscopic hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2012 Nov 1;207(5): 382.e1-382.e9.

- Rajappa GC, Vig S, Bevanaguddaiah Y, Anadaswamy TC. Efficacy of pregabalin as premedication for post-operative analgesia in vaginal hysterectomy. Anesthesiol Pain Med. 2016 Jun 1;6(3).

- Korsholm M, Mogensen O, Jeppesen MM, Lysdal VK, Traen K, Jensen PT. Systematic review of same-day discharge after minimally invasive hysterectomy. Vol. 136, International Journal of Gynecology and Obstetrics. Wiley Blackwell; 2017. p. 128–37.

- Dedden SJ, Geomini PMAJ, Huirne JAF, Bongers MY. Vaginal and Laparoscopic hysterectomy as an outpatient procedure: A systematic review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2017 Sep 1; 216:212–23.

- Bailey CR, Ahuja M, Bartholomew K, Bew S, Forbes L, Lipp A, et al. Guidelines for day‐case surgery 2019. Anaesthesia [Internet]. 2019 Jun 8 [cited 2020 May 31];74(6):778–92. Available from: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/anae.14639

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/43854/304-fergusson.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=2077#collapse10

Jessica Chang General Surgical Specialty Registrar

Christodoulos Neophytou General Surgical Specialty Registrar

Sian Davies General Surgical Specialty Registrar

Emma Howard Foundation Doctor

Andrew Houghton Consultant Vascular and Endocrine Surgeon

Authors, address

Shrewsbury and Telford NHS Trust, Mytton Oak Road, Shrewsbury SY3 8XQ

Corresponding author Jessica.chang@nhs.net

Keywords Same-day discharge; parathyroidectomy; day-case.

Abstract

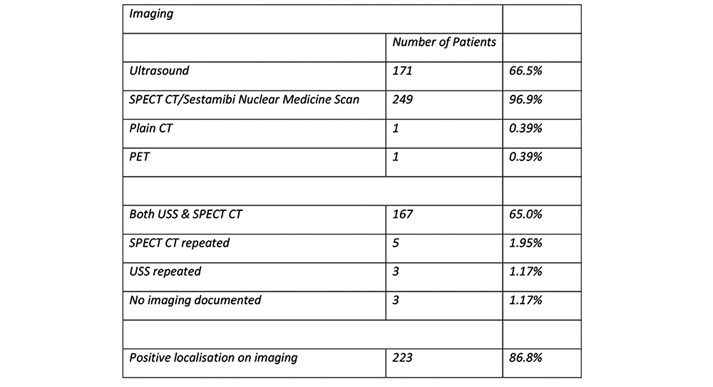

Introduction: Despite a shift towards same-day discharge in many surgical departments, true day-case rates remain low following parathyroidectomy (10% nationally in UK). Our standard practice is same day discharge for all patients having surgery for primary hyperparathyroidism. Patients are discharged on oral calcium/vitamin D with outpatient calcium checks day 6 - 7 and follow up day 10. Our retrospective study assesses the safety of this practice.

Methods: All patients undergoing parathyroidectomy for primary hyperparathyroidism (bilateral or unilateral neck exploration) were identified between 01/01/2010 and 30/12/2019. Patients with renal hyperparathyroidism were excluded. Demographics, histology, biochemical results, and length of stay were extracted from patient records.

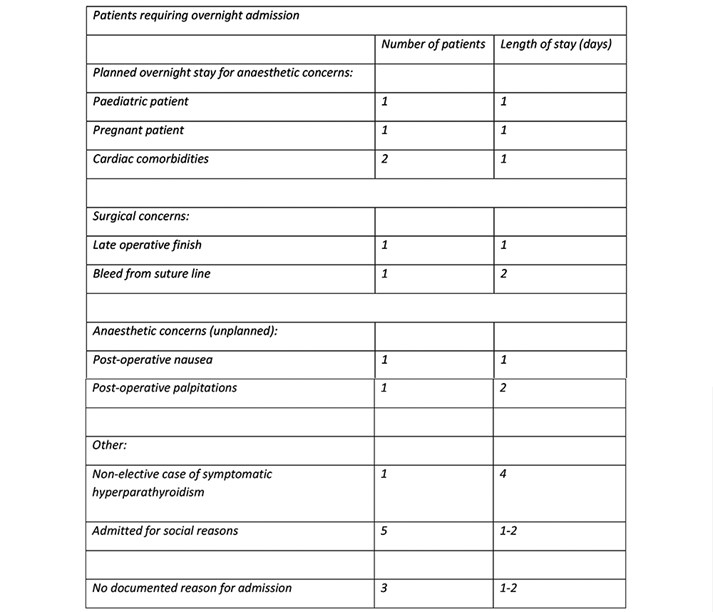

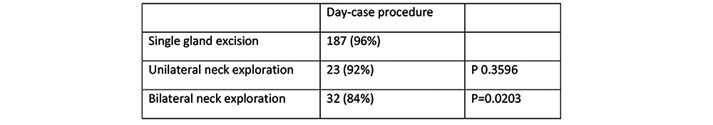

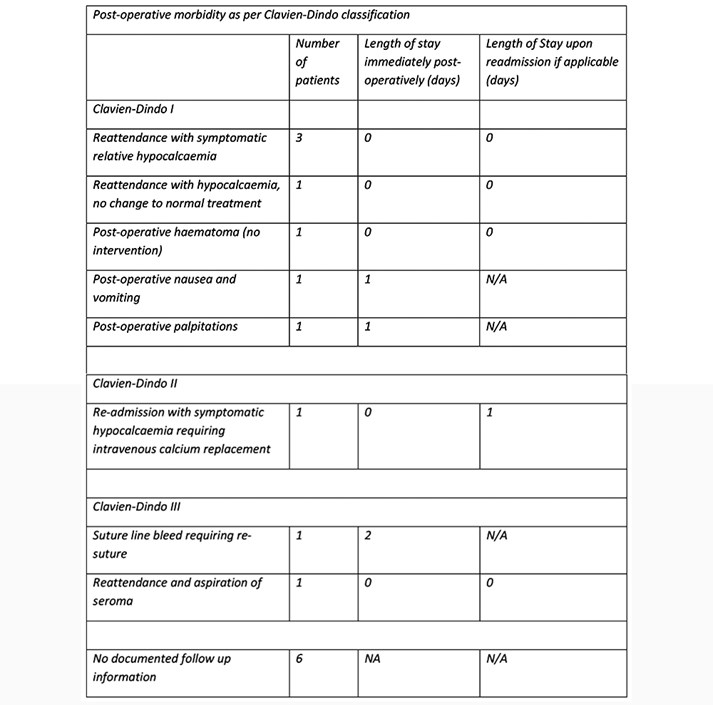

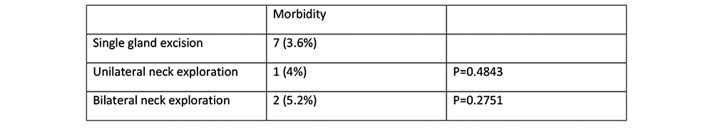

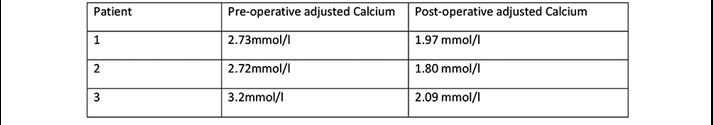

Results: 257 parathyroid procedures for primary hyperparathyroidism were performed during the study period. The cohort included 199 females, median age of 63 (range 15 – 88). Day-case procedures were carried out in 93.0%, with 17 requiring overnight admission for anaesthetic/social reasons (length of stay 0 – 4 days). Three patients presented postoperatively with symptoms of relative hypocalcaemia despite being biochemically normo-calcaemic, a single patient requiring intravenous calcium for symptomatic hypocalcaemia (adjusted calcium 1.8mmol/l).