Tim Rowlands

Tim Rowlands

We end one year and move into 2018. We’ll no doubt see many new day case developments in the coming year.

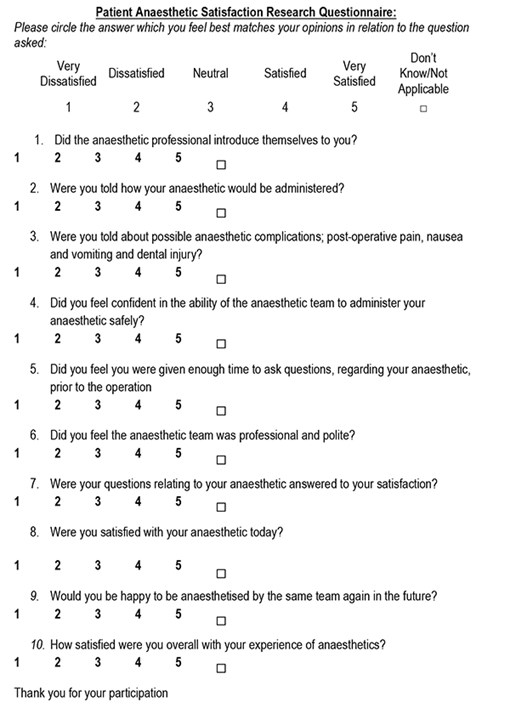

In this edition there are several widely different articles which I hope you will find topical and interesting. I mention several here: Raja et al looked at the implementation of a pathway for improving post operative discharge, demonstrating reduced rates of urinary retention. Deshmukh and Belfield looked at a rather neglected topic of compartment syndrome in the day case orthopaedic setting. Howard Cox presents questionnaire results from a study of patients’ attitudes to physician assistants in anaesthesia in his institution.

I am about to step down as Editor of the Journal of One Day Surgery; for edition 28.1 we will have a new one, David Bunting, a consultant surgeon and current member of BADS Council. I would like to wish him every success in the role. I would also like to thank our President, Mary and the rest of the team at BADS past and present who have helped and supported me (or aided and abetted; delete as appropriate) in my time as Editor and on Council.

Tim Rowlands

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6171/274-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1189#collapse0

Mary Stocker

Mary Stocker

As the year draws to a close it seems a natural time to reflect on all that has been achieved within 2017 and look forward to the challenges and opportunities awaiting us next year.

I am delighted to report that our association has grown by over 10% in 2017 so welcome to all our new members and welcome back to those who have been with us somewhat longer! We have been busy over the last few months developing the membership benefits offered to you.

Our website has been revamped and hopefully is clearer and easier to navigate. I would like to highlight to you two new areas of the website which may be of interest to you.

1. Benchmarking Resource

We were very disappointed to learn this year that the Better Care Better Values sight previously hosted by NHS Digital was to be decommissioned. In recent years this has provided us will valuable benchmarking information enabling us to identify day surgery rates for individual hospital trusts for all the procedures within the BADS Directory. The team at NHS digital have generously provided us with a very useful spread sheet which we have linked too through the resources section of our website. This allows you to benchmark your trusts day surgery performance against our 200 procedures over the last two years. Benchmarking of activity is one of the key priorities for BADS and we are now working closely with NHS Improvement to develop a tool which enables you not only to clearly identify your trusts day case rates across our entire range of procedures but also to see who the national top performers are for each procedure so we can all learn from our national experts. We also hope to be able to add some additional information around unplanned admission rates for each procedure as a measure of quality of your day surgery service – watch this space.

2. Day Surgery Dilemmas

You will also notice a new Day Surgery Dilemmas section within the website where we hope to build a series of documents giving advice on some of the key dilemmas that you, our members raise with us. Anna Lipp has kindly authored the first of these on Venous Thromboembolism, more to follow – if you have any hot topics you would like addressed please send them in to us.

Council are currently working to update our list of day surgery units and contact people across the UK. We will soon be contacting you to ask for the name of your day surgery unit and the medical and nursing lead for day surgery within your trust. Having this information will ensure that we can spread day surgery information more efficiently to a wider audience so please do help us to get our contacts up to date.

Education via national conferences is a large part of BADS work. In November we ran another successful conference focussing on emergency day surgery in collaboration with Healthcare Conferences. This topic continues to be of great interest and a range of challenging and inspiring speakers certainly stimulated lots of constructive discussion. If you missed the chance to attend keep an eye on the website as we hope to re-run this event in the spring. Plans for our ASM in Sheffield are coming together and our conference secretaries Kim Russon and Fiona Belfield have developed an excellent programme. Registration opens in January as does abstract submission so do get those projects finished and written up in time to submit by the end of March. We are delighted that we have been invited to run a session at the Association of Anaesthetists Winter Scientific Meeting in January 2019 and are busy putting a programme together for this which will provide an excellent opportunity to showcase day surgery developments to the wider anaesthetic community.

Finally we have recently been approached by a television production company who are interested in commissioning a documentary series about day surgery for the BBC so hopefully everyone will be talking about Day Surgery in 2018!

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6172/274-pres.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1189#collapse1

Authors: N Deshmukh1 & F Belfield2

- Dept. Trauma and Orthopaedics, Withybush General Hospital, Fishguard Road, Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire SA61 2PZ, UK.

- Dept. Day Surgery, Withybush General Hospital, Fishguard Road,Haverfordwest, Pembrokeshire SA61 2PZ, UK.

Corresponding author: F Belfield-Tel 01437773277 Email: Fiona.belfield@wales.nhs.uk

Keywords: Compartment syndrome, Day Surgery Trauma Pathway, awareness

Abstract

Compartment syndrome is a pathological condition characterized by a micro vascular insult in a closed soft tissue compartment [1]. By recognising the signs and symptoms of this condition quickly it can be treated with intervention and minimal fiscal implications.

To assess the knowledge of Day Surgery Nurses regarding this condition, a questionnaire was developed, then following results of the questionnaire several actions were put in place to raise the awareness, this questionnaire was then re distributed to see if the knowledge had increased.

Introduction

Compartment syndrome is a clinical diagnosis and if missed or not suspected it can cause devastating complications such as severe and permanent muscle atrophy, loss of sensation or even amputation, and in extreme circumstances it can result in loss of life [2].

Due to the recent introduction of a Day Case Trauma Pathway in Withybush hospital, it is vital that the nurses working in the Day Surgery environment are aware of compartment syndrome but more importantly they are competent and confident in recognising the signs and symptoms quickly to avoid the development of compartment syndrome. The Day Surgery setting is fast becoming an option for orthopaedic surgeons when admitting trauma patients that require surgical intervention.

The county of Pembrokeshire has a population of 375,000 however it is also a very popular tourist destination throughout the year, thus increasing this number greatly, of any potential patients that may require trauma surgery. If deemed fit patients would be able to be placed onto the Day Case trauma pathway thus freeing up the inpatient beds and reducing the length of stay.

The aim of this audit was to:

- Assess the level of awareness with regards to this condition amongst the Day Surgery Nurses who are often the first port of call in an emergency admission and

- To identify gaps in the knowledge regarding this condition. Therefore it is imperative that all staff dealing with these admissions are fully aware of the risks, signs and symptoms, and

- That they are confident in administering the appropriate medical and nursing interventions required in evaluation and monitoring of this extremely serious phenomenon.

Methods

To assess the initial awareness of Compartment Syndrome amongst Day Surgery Nurses a questionnaire was devised (fig1). The questionnaire was distributed to the Nurses for completion, which was anonymous. All the participants had the option of selecting a close question response in addition to multiple choice questions.

After the initial audit results were collated including definition, aetiology, symptoms, signs, immediate response on suspicion of compartment syndrome and the outcome if compartment syndrome if not recognised quickly. It was found that the awareness and knowledge regarding compartment syndrome was suboptimal.

An action plan was put in place and within the action plan there was a lecture open to all staff on Compartment Syndrome, RCN [3] (Fig2) and BOA [4] (Fig2) guidelines for Compartment Syndrome were displayed on the ward, also a poster with a flow chart detailing signs and symptoms which included guidelines on what to do if Compartment Syndrome is suspected. This acted as a quick systematic guide to follow and would aid in the early recognition on the condition.

The same questionnaire was then distributed 3 months later to close the loop of the audit to assess if the level of awareness had increased following the action plan following the initial audit and also to find out the impact of these interventions.

COMPARTMENT SYNDROME AWARENESS AMONGST DAY SURGERY NURSES

Please could you complete this questionnaire by placing a tick next to the most appropriate answer. There could be more than one answer for each question:

- Compartment syndrome is defined as:

- muscle damage within the compartment

- raised pressure within the compartment

- neurovascular damage within the compartment

- Compartment syndrome is commonly seen following:

- tibial fracture

- elbow fracture

- femur fracture

- proximal humerus fracture

- Common symptoms of compartment syndrome are:

- tingling sensation distally

- pain out of proportion to injury

- inability to move the toes / fingers

- -toes / fingers becoming pale

- Important signs to observe for compartment syndrome include:

- pain on passive stretch of the muscle involved in the compartment

- swelling of leg / forearm

- tense compartment

- muscle weakness distally

- sensory loss distally

- capillary filling > 2 sec

- Immediate response after suspecting compartment syndrome, should be

- Limb elevation

- Opioid analgesics

- Call SHO / Call Registrar if SHO not available

- Split POP down to skin and keep the plaster on

- Remove the plaster

- Complications/consequences of compartment syndrome are:

- Permanent distal muscle weakness

- Permanent distal sensory loss

- Limb loss

Figure 1 RCN GUIDELINES [3]

Figure 2 BOA GUIDELINES [4]

Results

All the participants were on duty when the questionnaire was distributed at initial audit and then re audit 3 months later; therefore the response rate was 100% on both occasions. 17 participants completed the initial questionnaire and 14 completed the re audit.

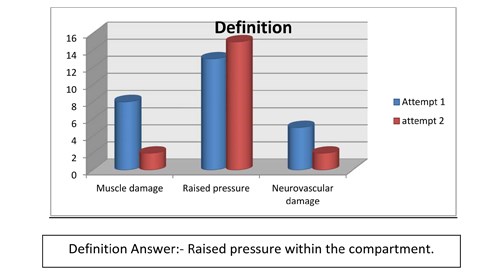

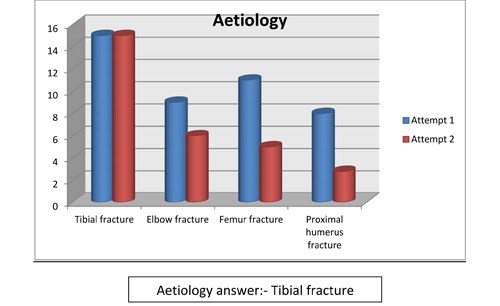

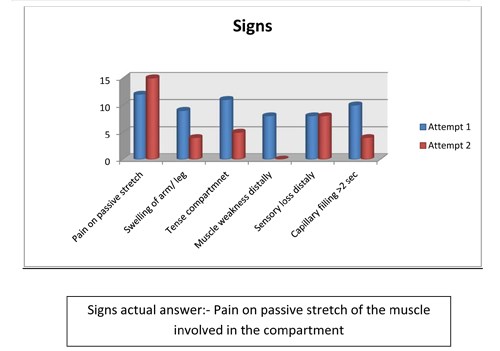

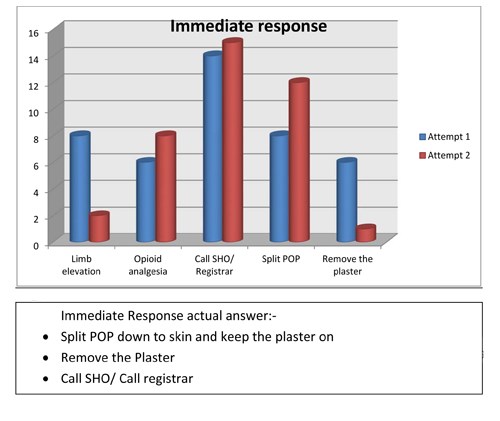

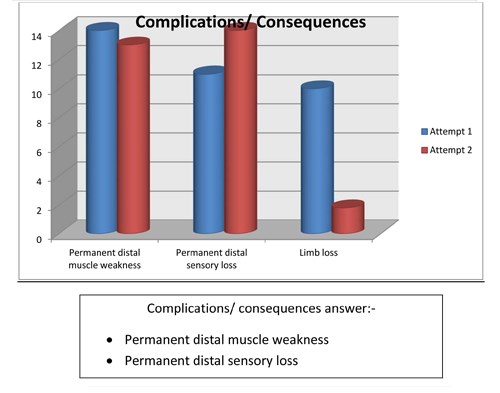

The majority of staff at the first audit was able to identify some obvious answers but it was apparent that they lacked understanding of compartment syndrome, awareness was limited and the knowledge was basic - there was a shortfall in understanding and assessing compartment syndrome. Using the results it was found that compartment syndrome is poorly understood and its awareness suboptimal. Specific answers were not recognised and there was a tendency to choose all the answers when completing the questions. This may indicate that the questionnaire was not set out clearly, with a suggestion that there could be one or more answer for each question and that the staff did not want to risk missing out a vital answer. However as you can see from the graphs shown (Figures 3-8) it does indicate at re audit, that there has been an increase of knowledge and an increase in confidence in answering the questions, as the answers are more specific and correct, although we have to consider that there were 3 less staff who completed the questionnaire in the re audit.

Figure 3

Figure 4

Figure 5

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

Discussion

As stated compartment syndrome is a surgical emergency and early recognition is emphasised. Severe limb injury and long duration of surgery are two of the most common causes of compartment syndrome. Decreased awareness can lead to delaying the diagnosis and therefore critical decision making. Day surgery nurses need to understand the fact that it is a potentially life threatening condition and predicting and managing acute compartment syndrome is important to improve health outcomes. As they are very often the first port of call in emergency situations, suspicion of raised compartmental pressure, early recognition, and promptness in notifying the on call doctor is of vital importance if limb function is to be preserved and complications are to be avoided.

This audit identified gaps in the knowledge and awareness of the Day Surgery nurses, which was highlighted in the first audit, also and the need for support through policies and evidence based practice guidelines to improve the inadequate and suboptimal knowledge about the condition.

The audit was imperative to assess the knowledge of the nurses, due to the introduction of the Day Case Trauma Pathway, it was essential that we gave them as much guidance when dealing with Compartment syndrome, as early recognition is vital if the patient is to make a full recovery from this condition.

Nursing is a dynamic, evolving profession and all staff is accountable to safe and effective patient care. With annual PADRs and revalidation, the standard of practice has to be maintained with a more proactive approach. One strategy was to provide existing guidelines from RCN [3] and BOA[4] (Figure 2).

At re-audit there was notable improvement that was identified, which is encouraging, it shows that the Nurses within the day Surgery Unit are motivated in wanting to learn new skills and are able to adapt to new services when introduced within the department. The audit encouraged healthy debates amongst the staff, which has lead to their increased knowledge in this area and certainly has raised their awareness when patients are admitted via the Trauma pathway, which was the intention of this study.

Conclusion

Day surgery nurses knowledge of compartment syndrome was suboptimal as they rarely had to care for Trauma patients. Given the introduction of the Trauma Pathway it is now essential that they are aware of this potential life threatening condition and more importantly are confident in treating and knowing how to act if it is suspected.

With the introduction of the poster, flowchart, guidelines and the lecture has improved the knowledge of the Nurses in Day Surgery and they feel confident and competent in looking for the signs and symptoms. Compartment Syndrome is always at the fore of their minds when caring for all Trauma patients and the nurses are thinking about this potential complication. We have now introduced regular education and training to all the staff nurses, which are given by senior members of the Day Surgery team and we have also developed a close working relationship with the Trauma Pathway Coordinator.

References

- Galyfos G, Gkovas C, Kerasidis S, Stamatatos I,Stefanidis I, Giannakakis S,Geropapas G, Kastrisios G,Papacharalampous G and Maltezos C (2016) Acute Compartment Syndrome of the Lower Extremity: Update on Proper Evaluation and Management. Journal of Vascular and Endovascular Surgery 2016;2:10 1–3.

- Von Keudell AG, Weaver MJ, Appleton PT, Bae DS, Dyer GS, et al. (2015) Diagnosis and treatment of acute extremity compartment syndrome. Lancet 2015;386:1299–1310.

- RCN [webpage on the internet}. Actut limb Compartment Syndrome observation chart; 2016. Available from: https://www.rcg.org.uk/professional-development/publications/pub-005457. Accessed 1st June 201.7

- BOA.BOAST 10: Diagnosis and Management of Compartment Syndrome of the limbs; 2016. Available from: https://www.boa.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/BOAST-10.pdf. Accessed 1st June 2017.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6175/274-deshmukh.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1189#collapse2

Authors: Louise Dunphy1, Elamin El-Shaikh2 & Mazhar H. Raja3

1Core Surgical Trainee, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

2Senior House Officer in General Surgery, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

3Consultant General Surgeon, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

Department of General Surgery, Milton Keynes University Hospital, Eaglestone, Standing Way, Milton Keynes MK6 5DL.

Telephone number: 01908 660033 Email: dunphylmb@gmail.com

Abstract

Gallstone ileus is an uncommon but intriguing entity, representing 1-4% of all hospital presentations with small bowel obstruction. Approximately 25% of cases involve patients over 65 years of age, thus contributing to the high mortality and morbidity reported. Symptoms are often vague, requiring a high index of suspicion for successful diagnosis. We present the case of a 79 year old Caucasian female presenting to the Emergency Department with a 24 hour history of abdominal pain, distension and faeculant vomiting. She reported multiple co-morbidities but no previous abdominal surgeries were noted. Following failed conservative management, she underwent an emergency laparotomy and a

2cm gallstone was identified in the mid ileum. The gallstone was digitally crushed and milked into the caecum. This case highlights the importance of considering gallstone ileus in the differential diagnosis in an elderly patient presenting with signs of small bowel obstruction and no previous abdominal surgeries.

Keywords: small bowel obstruction, gallstone ileus, enterotomy.

A 79 year old Caucasian female presented to the Emergency Department with eight episodes of faeculant vomiting, abdominal distension and generalised colicky abdominal pain over a 24 hour period. Multiple co-morbidities were recorded including: type 2 diabetes, ischaemic heart disease, hypertension, atrial fibrillation and chronic kidney disease. A strong family history of bowel cancer was noted. In addition, she sustained a subdural haematoma when taking warfarin and consequently her pharmacological management included aspirin and beta blockers. She was a non-smoker and did not consume alcohol. The following observations were recorded: temperature 36.90C, BP 116/75mmHg, HR 88, SpO2 98% on air and RR15. Respiratory and cardiovascular examination were unremarkable.

Her abdomen was soft and slightly tender on palpation, with no obvious mass or hernia. No guarding or rebound tenderness was elicited and bowel sounds were present on auscultation. PR examination confirmed a small amount of soft faeces in the rectum. Her bowels opened 48 hours previously.

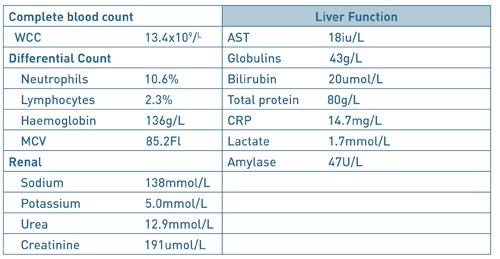

Baseline serological investigations revealed a normal serum amylase [47 iu/l], WBC 13.4, Hb 136, CRP 14.7 with normal renal and liver function. [Table 1] A venous blood gas confirmed a lactate of 1.7. Urinalysis was negative. An erect chest radiograph identified no free air beneath the diaphragm [Fig.1] Her abdominal radiograph revealed dilated small bowel loops. [Fig.2] She was reviewed by the oncall surgical team and the clinical impression was of small bowel obstruction. Further investigation with a CT abdomen and pelvis suggested features of small bowel obstruction at the mid- ileal level. At the transition point, appearances were those of a faecolith. [Fig.3] The differential diagnosis included gallstone ileus, due to her un-operated abdomen or a fungating tumour [thought unlikely].

Table 1. A mildly elevated WCC and CRP were observed. Her amylase was normal.

Fig. 1. AP erect chest radiograph. There was no free air beneath the diaphragm.

Fig. 2. An erect abdominal radiograph. The bowel gas pattern was unremarkable.

Fig.3. CT Abdomen and Pelvis. Features are suggestive of small bowel obstruction at mid ileal level. At the transition point, appearances were those of a faecolith.

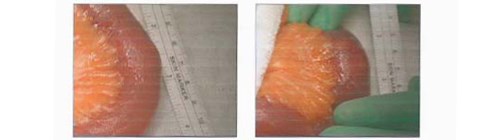

Fig.4. Gallstone. Following examination of her small bowel, a 2cm gallstone was identified in the mid ileum.

A nasogastric tube and catheter were inserted and IV fluid resuscitation was initiated, with strict fluid balance monitoring. Following 24 hours of conservative management with an unresolved small bowel obstruction, surgical exploration was indicated. Under general anaesthesia, a midline laparotomy incision was performed. Her small bowel was examined and a 2cm gallstone was identified in the mid ileum. [Fig. 4] No perforation or free fluid were present and the gallbladder was normal in appearance. No fistula was identified. The gallstone was crushed with gentle digital pressure and milked into the caecum. An enterotomy was not performed. Postoperatively, she made slow progress due to tachycardia and persistent nausea. She was reviewed by the cardiology team and treatment commenced with bisoprolol 1.25mg od and digoxin 125mcg. An outpatient ECHO was requested. She was discharged uneventfully 16 days post admission, with her prolonged stay due to her underlying medical co-morbidities.

Discussion

Dr. Erasmus Bartholin, a Danish physician first described gallstone ileus following an autopsy examination in 16541. He postulated that the gallstone enters the gastrointestinal tract through a biliary enteric fistula, with the terminal ileum being the most frequently involved site. Interestingly, the term “gallstone ileus” is a misnomer, as the condition is a mechanical obstruction of the gut and not a true ileus2. The gallstone may also enter the gastrointestinal tract following ERCP and sphincterotomy. The most common site of impaction is the distal ileum [50-75%] owing to its narrow intra-luminal diameter, followed by the jejunum [20-40%] and the stomach3. The gallstone must be at least 2-2.5cm in diameter to cause an obstruction. In 1896, Bouveret’s Syndrome was described and it occurs when a fistula forms between the gallbladder and the stomach or duodenum allowing a gallstone to migrate into the duodenum causing gastric outlet obstruction4. It occurs in approximately 10% of cases.

The classical presentation of gallstone ileus has been defined as having a “protracted history” with the majority of patients suffering with abdominal pain and vomiting for at least three days prior to presentation5. Constipation also predominates, usually intermittently as the stone travels through the bowel. Diagnosis is often delayed as a history of biliary symptoms is variable, with a history of cholelithiasis present in only 50%. Perforation of the small intestine proximal to the obstructing gallstone is rare, with less than 10 cases reported in the literature. Gallstone ileus has a predilection for females with 25% of all cases involving patients over 65 years old and the mean age has been reported as 72 years. Consequently, multiple co-morbidities exist and contribute to the high mortality and morbidity rates.

Radiological investigations, including an abdominal x-ray may demonstrate signs of small bowel obstruction or a calcified gallstone in the intestinal lumen. It is important to remember that only 15% of gallstones are radiopaque6 and the sensitivity of plain radiographs alone is poor, ranging from 40– 70%7. Air in the biliary tree (pneumobilia) may also be observed. CT has a sensitivity and specificity of 93% and 100% respectively8 and is useful for identifying the transition point between dilated and collapsed bowel. Rigler’s triad is the criteria used to determine gallstone ileus on a CT scan9, with the components including pneumobilia, an ectopic gallstone and small bowel obstruction. However, gallstone ileus is more typically diagnosed at laparotomy in a patient undergoing surgery for unexplained small bowel obstruction9.

But what about treatment modalities? Resolving the obstruction can usually be achieved by enterotomy and removal of the gallstone, but the dilemma of how to manage the fistula from the gallbladder to the intestine remains. Its management remains controversial with open surgery including enterolithotomy or single stage enterolithotomy with cholecystectomy and fistulectomy with cholangiography if deemed necessary2 being the mainstay of treatment. Indeed, other approaches have been utilised including: laparoscopic surgery and lithotripsy10. In an elderly patient and in the presence of severe inflammation and adhesions, Windsor10 advocates simply removing the stone and leaving the fistula and gallbladder untouched.

So, what does the literature suggest? The first large case series of gallstone ileus, involving 131 cases, with a mortality of 44% from 125 operations was reported by Courvoisier in 189011. To date, the largest review consists of 1001 reported cases and was published by Reisner and Cohen in 199412. In this combined series, mortality rates of 16.9% for one stage and 11.7% for enterolithotomy were reported12. The recurrence of gallstone ileus is rare but Webb13 and Hussain14 have reported a 5% recurrence rate in patients suffering from one episode of gallstone ileus.

In conclusion, gallstone ileus is an uncommon complication of cholelithiasis but an established cause of mechanical bowel obstruction in the elderly. Despite advances in imaging techniques and the reported sensitivity and specificity of CT8, gallstone ileus remains a diagnostic challenge for the clinician and pre-operative diagnosis is often delayed. However, due to the current demographic shift towards an elderly population, it continues to have a high mortality and morbidity rate. Hence, elderly patients, especially those > 65 years, presenting with symptoms of small bowel obstruction and no previous abdominal surgeries, gallstone ileus should be included in the differential diagnosis.This Case Report highlights the fundamental importance of including gallstone ileus in the differential diagnosis in an elderly patient presenting with abdominal pain and signs of obstruction.

References

- Deckoff SL. Gallstone ileus: a report of 12 cases. Ann Surg 1955;142:52–65.

- Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281.

- Kasahara Y, Umemura H, Shiraha S, Kuyama T, Sakata K, Kubota H. Gallstone ileus. Review of 112 patients in the Japanese literature. Am J Surg 1980;140:437–440.

- Cappell MS, Davis M. Characterization of Bouveret’s syndrome: a comprehensive review of 128 cases. Am J Gastroenterol 2006;101:2139–46.

- Browing LE, Taylor JD, Clark SK, Karanjia N. Case Report: Jejunal perforation in gallstone ileus – a case series. Journal of Medical Case Reports 2007;1:157.

- Lassandro F, Romano S, Ragozzino A, Rossi G, Valente T, Ferrara I, Romano L, Grassi R. Role of helical CT in diagnosis of gallstone ileus and related conditions. Am J Roentgenol 2005;185: 1159–1165.

- Rippoles T, Miguel-Dasit A, Errando J, Morote V, Gomex-Abril SA, Richart J. Gallstone ileus: increased diagnostic sensitivity by combining plain film and ultrasound. Abdom Imaging 2001;26:401–5.

- Yu CY, Lin CC, Shyu RY et al. Value of CT in the diagnosis and management of gallstone ileus. World J Gastroenterol 2005;11:2142–7.

- Michele D, Luciano G, Massimiliano F et al. Usefulness of CT scan in the diagnosis and therapeutic approach of gallstone ileus: report of two surgically treated cases. BMC Surg 2013;13:6.

- Windsor A, Heriot A. The small intestine. In: Bumand KG, Young AE, Lucas J (eds). The New Aird’s Companion in Surgical Studies, 3rd edn. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2005:623-44.

- Courvoisier LT. Case series and statistics of pathology and surgery of the bile ducts. F.C.W. Vogel 1890. Surg Clin North Am 1982, 62:247.

- Reisner RM, Cohen J. Gallstone ileus: a review of 1001 reported cases. Am Surg 1994, 60:441-446.

- Webb LH, Ott MM, Gunter OL. Once bitten, twice incised: recurrent gallstone ileus. Am J Surg 2010, 200:72-74.

- Hussain Z, Ahmed MS, Alezander DJ et al. Recurrent recurrent gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010, 92:4-6.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6176/274-dunphy.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1189#collapse3

Authors: Ajit Dhillon & Tim Rowlands

Derbyshire Vascular Services, Royal Derby Hospital, Derby.

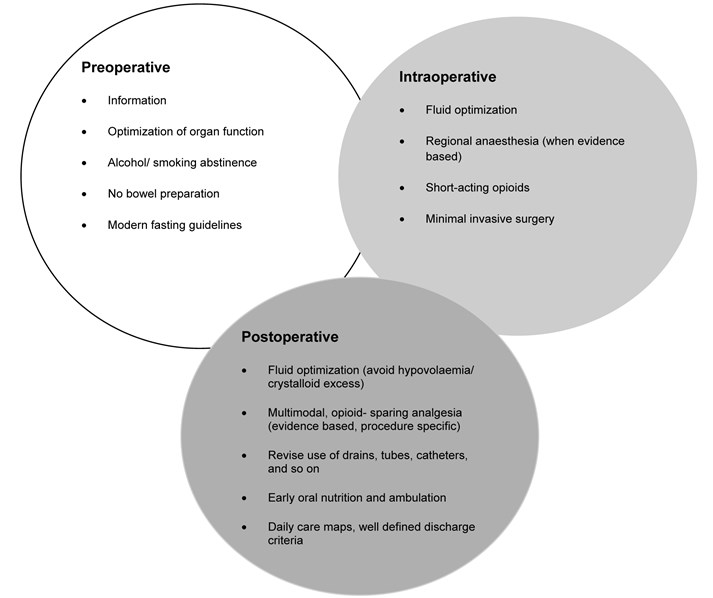

Enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) also known as fast track surgery is a multimodal post-operative recovery programme. It is based on the concept that postoperative recovery is determined by numerous factors associated with the preoperative, intraoperative and postoperative phases. The preoperative phase where existing organ dysfunction is recognised and improved; the intraoperative phase, which is determined by the anaesthetic and surgical techniques, and, postoperative phase which concentrates on analgesia, fluid management, nutrition, mobilization, nursing care and a planned recovery programme. It is a multi-disciplinary approach with an emphasis on regional anaesthesia and postoperative non-opioid analgesia being used sparingly. As more specialities take on board the ERAS model, it is being recognised that a procedure-specific approach is important (Kehlet, 2009)1. The goal of ERAS is not necessarily about reducing length of stay but to achieve a pain and risk free operation whilst recognising the postoperative stress response with inevitable organ dysfunction (Kehlet, 2015)2.

The usefulness of ERAS is well established in colorectal surgery but there is very limited literature about its application in major, non-cardiac vascular surgery. The principles of ERAS in their current form, as shown in Figure 1 (Kehlet, 2009)1, may not all be relevant to non-cardiac vascular surgery but, with appropriate modification may prove useful.

We aim to review the factors that are known to extend length of postoperative stay and associated with mortality as a method of assessing modifiable factor that may contribute towards a procedure specific ERAS approach in open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA), carotid endarterectomy (CEA), infra-inguinal lower extremity bypass (LEB) and major lower limb amputation (LLA). We have excluded asymptomatic patients undergoing CEA as there is still little clarity in practice.

Figure 1. Principles of the fast- track methodology to enhance postoperative recovery (must be procedure specific).

Open repair of abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA)

A non-randomised prospective study of ERAS in open repair of AAA involved the implementation of a modified ERAS programme in 52patients undergoing surgery after 2008, and, conventional care in 75 patients operated upon prior to 2008. The modifications included counselling in the out-patient setting and upon hospital admission; the day before surgery patients were permitted a low residue diet until the evening, followed by an enema and permitted to drink fluids and juices until the morning of the day of the surgery. In the post-operative phase, patients were allowed to drinks fluids 3hours after extubation, with administration of pro-kinetic anti-emetics. Patients were encouraged to consume high calories in the form of fat emulsions alongside administration of amino acids and glucose. The surgical wound was protected with a specified highly waterproof dressing. Post-operative transfusion was kept to a minimum, only to maintain haemodynamic stability. The only statistically significant difference between the groups was coronary artery disease, 36% and 57.7% respectively, p=0.04. Postoperative complications in the ERAS group consisted of one case each of deterioration in renal function, surgical site infection and anastomotic stenosis. Yet in the conventional care group 8patients had complications, 2 cases of deteriorating renal function, 3 cases of surgical site infection, 2 cases of pneumonia and 1 case of cerebral infarction. Ileus is the most widely recognised primary morbidity associated with an open repair of AAA. Patients in the ERAS group were allowed to resume a diet when they started to pass flatus, this shortened the time to meal consumption to 59+/- 15hours after surgery compared with 93+/- 25hours in the conventional management group. The shorter length of stay was statistically significant in the ERAS group at 9+/- 3day compared with 16+/- 5days (p=0.001) in the conventional management group (Tatsuishi, 2012)3. Impaired lung function has been shown to have an inverse association on length of stay following elective open repair of AAA. Preoperative lung function tests to assess forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1), with FEV1 <1.9L was associated with a mean stay of 15.0 +/- 1.43 days, reducing incrementally with increasing FEV1 until patients with FEV1 >2.5L, had a mean stay of 11.2 +/- 0.3days. Impaired respiratory function will have an existing negative impact on a patients functional ability but will also increase the risk of postoperative prolonged intubation, development of pneumonia and respiratory failure. Preoperative smoking also increased length of stay although it failed to reach statistical significance. Preoperative blood results such as haemoglobin levels, patient age and gender, previous myocardial infarction failed to show an impact on length of stay. Preoperative myocardial infarction was not directly associated with postoperative myocardial infarction (UK Small Aneurysm, 1998)4.

Chang et al report (Chang, 2003)5 outcomes of a modified early form of ERAS type pathway. The patients were counselled pre-operatively, that their expected length of stay (LOS) would be less than 5day without complications. The main difference compared with the currently accepted ERAS pathway was routine intra- and post-operative monitoring with arterial as well pulmonary artery catheterisation, and, liberal administration of intra-venous fluids in the first 24-48hours to allow for third-spacing and based on pulmonary catheter monitoring. The mean LOS for ‘complicated recovery’ was 13.8+/- 6.7days but 6.9+/- 2.9 days in ‘uncomplicated recovery’. Kaplan- Meier analysis of factors significantly increasing LOS in the pre-operative phase were age above 75years of age and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD); intra-operative factors including blood loss more than 500ml, duration of surgery more than 5hours; post-operative factors including any complications but specifically wound infection. Factors that would be expected to affect LOS but did not in this study was history of cardiac disease including coronary artery bypass graft (CABG), myocardial infarction (MI), congestive heart failure (CHF), aortic stenosis and ventricular arrhythmia. The data was re-analysed using Cox regression and the significant pre-operative factors prolonging LOS were age over 75years and COPD and, any post-operative complications. Duration of surgery above 5hours (p=0.684) and the arbitrary threshold of 500ml blood loss did not reach statistical significance. A further review (Huber, 2001)6 of outcomes after open repair of AAA in 16, 450 patients with mean age 72+/- 7 years not following an ERAS type pathway reported a median LOS of 8 days (mean 10.0 +/- 8.1). The factors associated with in-hospital mortality were increasing age, 70-79years, odds ratio (OR) 1.8 and, over 79years, OR 3.8; female gender, OR 1.6. The presence of more than 3 co-morbidities, OR 11.2, whereas presence of 2-3 co-morbidities had OR 3.2 but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.06). The individual pre-operative co-morbidities associated with increased mortality were cerebrovascular disease OR 1.8, renal insufficiency OR 9.5, whereas COPD did not reach statistical significance with OR 1.0 and p= 0.67.

UK registry data for a 3-year period, January 2012 to December 2014 for open and endovascular repair of AAA found that (Watson, 2015)7 reported the median LOS post open repair was 8days (range, 7-12days), including up to 2days spent on a level 2 or 3 critical care unit in 95% of cases, before returning to the main ward. Post-operative ‘defined complications’ refer to body systems but no specific complications. The nationally reported complications were cardiac 5.7% (95% CI 4.6- 7.0), respiratory 12.3% (95% CI 10.7- 14.1), haemorrhage 2.1% (95% CI 1.4- 2.9), limb ischaemia 3.3% (95% CI 2.4- 4.3), renal failure 4.2% (95% CI 3.3- 5.4) and, other 0.8% (95% CI 0.4- 1.4). 6.7% (95% CI 5.5- 8.1) returned to theatre and 30-day re-admission rate of 5.7% (95% 4.4- 7.3%). The in-hospital risk- adjusted mortality for elective open repair of AAA was 3.0%.

A prospective randomised trial (Muehling, 2009)8 in patients undergoing open repair of infra-renal AAA using the basic elements of ERAS; no bowel preparation, reduced pre-operative fasting, patient controlled epidural analgesia, enhanced post-operative feeding and post-operative mobilisation. Fewer of the ERAS group (6.1% versus 32%, p=0.002) required post-operative ventilation, earlier enteral feeding in the ERAS group (5 versus 7days, p<0.0001) and fewer post-operative complications (16% versus 36%, p=0.039). The LOS was shorter in the ERAS group (10 days versus 11 days, p=0.016) with 0% mortality rate in both groups.

A pooled analysis of case series (Gurgel)9 analysing the cumulative results for 1, 250 patients following an ERAS pathway and 1, 429 patients following a conventional care pathway found a mortality rate of 1.51% (95% CI 0.009, 0.0226) and 3% (95% CI 0.0183, 0.0445) respectively. The post-operative complication rate was 3.82% (95% CI 0.0259, 0.0528) and 4% (95% CI 0.03, 0.05) respectively. Sub-group analysis of post-operative complications found acute MI, 1.77% (95% CI 0.0103, 0.0270) and 2.9% (95% CI 0.019, 0.042); renal failure requiring renal replacement therapy, 2.79% (95% CI 0.0159, 0.432) and 0.69% (95% CI 0.0030, 0.0123); stroke, 0.26% (95% CI 0.0005, 0.0063) and 1.8% (95% CI 0.0091, 0.0299) respectively. The authors cite clinical and methodological heterogeneity between the case-series included in the pooled analysis. This included difference in the elements and indeed the number of ERAS elements implemented in each series. This may be a large contributing factor to their conclusion that outcomes were similar in both ERAS and conventional care groups.

Carotid endarterectomy (CEA)

The UK guideline issued by National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 10 recommend a 2week target from initial symptoms to surgery and accept that some patients may become symptomatic with a carotid artery stenosis of 50- 99%. The UK registry for Jan- Dec 20147 analysed data submitted for 4862 interventions carried out on 4464 patients undergoing. A majority of 44.9% patients had an occlusion of 70-89%, 24% had 50-69% stenosis and 28.8% had 90-99% stenosis. 92.4% of patients were already commenced on anti-platelet therapy, 87.4% on statin therapy, 25.6% on beta-blocker therapy and 37.4% on ACE inhibitor therapy. There was variation in surgical and anaesthetic techniques employed such as 52% of patients had general anaesthetic only compared with 27.3% receiving local anaesthetic. Carotid shunt was used in 49.6% of cases with 73.3% having endarterectomy and patch. Post-operatively, 45.8% of patients were admitted to either level 2 or level 3 critical care with a median LOS of 1 day in each. The overall LOS was 4 days (2-6). The recognised complications following CEA are MI, bleeding, cranial nerve injury and stroke. In the review period the complication rates for major complications were MI, 0.9% (95% CI 0.8- 1.1), bleeding, 2.8% (95% CI 2.6- 3.1), death and/ or stroke within 30days, 2.0% (95% CI 1.8- 2.2) and, cranial nerve injury, 1.6% (95% CI 1.4- 1.8)7. The registry data did not allow for analysis of when complications occurred and what factors delayed discharge.

A retrospective review of unit data (Sheehan et al; 2001) 11 for 835 consecutive patients found 62patients (8.0%) experienced either a neural deficit (26 patients, 3.4%) or neck haematoma (36patients, 4.7%) within 24hours of surgery. Further breakdown of those experiencing complications showed 24patients (66%) experienced neck haematoma and 19patients (73%) experienced neural deficit whilst still in the operating theatre or in the recovery area, 11patients (31%) had neck haematoma and 5patients (19%) had neural deficit within 8hours with the remaining patients exhibiting signs beyond 8hours. They excluded 64patients from the analysis because having had another operation, concomitant coronary bypass grafting or required heparinization. Unfortunately they excluded patient who experienced complications beyond the first 24hours10. A detailed review of 421 patients who underwent CEA carried out by 2neurosurgeons12 (Angevine et al, 1999), Cohort I, 171 patients had CEA following a conventional care pathway, Cohort II, 295patients had CEA when the unit was instituting a stay reduction policy on selected patients, and, Cohort III, 155 patients who had CEA after institution of a universal single-day stay policy. The mean age of patients in the cohorts was 70.1 +/- 0.6, 70.0 +/- 0.8 and 70.5 +/- 0.7 years respectively, 70.2+/- 0.4yearsfor the whole cohort. Pre-operatively, in the whole cohort, the symptomatic patients had >70% stenosis 75patients had suffered an ipsilateral stroke, 123 patients had suffered an ipsilateral transient ischaemic attack (TIA) or amaurosis fugax. 203patients were asymptomatic but had critical stenosis of >60%. Risk factor data was only available for 364patients (86%), 231 patients had hypertension, 115 patients had hypercholesterolaemia, 73patients had diabetes mellitus. All patients were assessed by Duplex scan and MRI. Only symptomatic patients continued intravenous heparin infusion up until surgery. All patients received 5000IU bolus of heparin prior to carotid artery cross-clamping and all patients were monitored by EEG and a shunt was used only when there was ≥50% decrease in amplitude of the alpha or beta frequencies, or loss of all cerebral activity. The carotid arteriotomy was closed primarily except in 1patient who underwent re-operation, or 2patients who had previously received radiation to the neck. These latter 3patients had vein patch closure. All patients stayed in intensive care for 1night post-surgery. There was no link between LOS and major complications. The complications deemed were death, MI or stroke. Mean post-operative LOS for the whole cohort was 2.1 +/- 0.2days; Cohort 1, 2.6 +/- 0.3 days; Cohort 2, 2.3 +/- 0.4 days; Cohort 3, 1.6 +/- 0.1 days with a statistically significant difference between Cohorts 1 and 2 (p< 0.0001) and Cohort 1 and 3 (p< 0.0001). 2patients (0.48%) died peri-operatively following ipsilateral ischaemic strokes (one each in Cohort 1 and 3). 2patients (0.48%) suffered MI but discharged haemodynamically stable. 13patients (3.1%) suffered a stroke, including the 2patients who died (Cohort 1, 7 (4.1%); 2, 3 (3.2%); 3, 3 (2.0%)). 7patients (1.7%) underwent re-operation, 3 for exploration of operated vessel for contralateral hemiparesis or hemiplegia with angiographic evidence suggesting thrombus or significant intimal flap, 2 for acute evacuation of neck haematoma, 2 for delayed drainage of wound infection. 13patients had nerve injury, 9 patients had injury to the marginal mandibular nerve, 2 patients had injury to the hypoglossal nerve and 2patients had mild hoarseness caused either by endotracheal intubation or retraction injury. All nerve injuries resolved by 6weeks post-CEA. They achieved a statistically significant, 20% reduction in the use of routine laboratory investigations including full blood counts. The study noted an increase in next day discharge from 32% to 70%, once all stakeholders had become ‘emboldened’ that patients did not require further observation beyond 18-24hours post- CEA. Any complications would manifest within this time.

Other factors that delay discharge beyond day 1 post- CEA include female gender; history of angina, valve disease, heart failure and cerebrovascular disease (Hernandez)13. Roddy et al14 reviewed reasons for prolonged stay beyond their critical pathway aim of discharge on day 1 after CEA, in their cohort of 188patients, found that the mean post-operative LOS was 1.65+/- 0.08 and total LOS was 2.17 +/- 0.14 days. 57% of patients were discharged home as intended on the pathway, on day 1 post-CEA. Significant factors for prolonged stay were post-operative complications such as TIAs (1%), MIs (1%), neck haematomas requiring surgical drainage (2.7%), small haematomas requiring observation for an extra day (2.1%), age >79years, diabetes mellitus, female gender and intravenous vasodilator therapy requirement. Previous atherosclerotic risk factors, previous neurologic symptoms, use of vasopressor agents and re-operation had a lesser association. The post-operative mortality from stroke was 1.6%14.

Whilst very few patients have isolated risk factors, the effect of having multiple risk factors such as age above 80-years, congestive heart failure, COPD, renal failure, contralateral carotid artery occlusion, recurrent ipsilateral carotid artery stenosis, ipsilateral hemispheric symptoms within 6weeks and, coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) within 6months in a retrospective review of 1370patients undergoing CEA between 1990 and 1999. 11 patients (0.8%) died; 6patients (0.4%) had disabling stroke and 10patients (0.7%) had non-disabling stroke. There was no statistical difference between outcome of death or stroke between patients with 1 or more risk factors (p=0.689) and no risk factors (p=0.681). The 20-day mortality was significantly greater in patients with 2or more risk factors compared to those without risk factors (2.8%, 0.3%p= 0.4). Only contralateral carotid artery occlusion was a significant predictor of adverse events (RR 4.3%, 95% CI 1.2-12.3; p=0.01) (Reed et al, 2003)15. Similarly, Halm et al16 found an adverse association between age above 80-years (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.50-2.54), contralateral carotid artery stenosis ≥50% (OR 1.44, 95% CI 1.45- 1.79) and coronary artery disease (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.20- 1.91).

An effort to comprehend the intra-operative factors that can lead to post-operative neurological deficit including stroke was noted in 63 of 2365patients operated on during the period 1965 to 1991, revealed there were more than 20different mechanisms that could be responsible. In 10 out of 66patients who had peri-operative stroke secondary to carotid artery injury related to clamping and de-clamping of whom 5patients had difficulty in placement of a shunt and 1patient becoming hypotensive whilst the shunt was in place, 1patient developed a bradycardia post-surgery thus reducing cerebral flow, the remaining patients suffered a stroke in the contralateral hemisphere likely secondary to a delay in shunt placement. Post-operative thrombus and embolism in 25patients in the immediate post-operative period, causing 9 out of15patients suffering a stroke whilst in the recovery area and 4 out of 15 patients having a stroke within 10hours of surgery, only 2 out of 15 patients had a stroke more than 24hours after surgery (6days and 14days later). All these patients had tolerated carotid artery clamping whilst under cervical block anaesthesia. Surgical exploration found technical defects leading to platelet aggregation such as clamp injuries, kinks in the redundant vessels, ledges at the end of the endarterectomy, stenosis at the closure of the arteriotomy and platelet aggregation on the synthetic patch material. The authors infer embolism as the cause of stroke in this group. In 10 out of 25patients labelled with delayed stroke secondary to embolic phenomena without thrombus present, they were managed conservatively. 8 out of 66patients had intracerebral haemorrhage having had a pre-operative stroke and, 4out 66aptients had transient ischaemic attacks (TIAs). 8out of 66 patients had a stroke not attributable to surgery or the reconstructed artery (Riles)17

Infra-inguinal Lower limb bypass

The in-hospital mortality in the UK, following lower limb bypass in 5387patient in 2014, were 2.7% (95% CI 2.3- 3.2). The registry noted 1 in 10 patients were re-admitted within 30-days of surgery but the reasons for this are unknown7. A series review of 4874patients over a 2year period, found the average LOS 7.5days. The independent risk factors for an arbitrarily defined protracted LOS of more than 8days were, distal bypass (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1-1.8); obesity (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1-1.5); partial functional dependence (OR 2.8, 95% CI 1.8- 2.4); history of cardiac disease (OR 1.5, 95% CI 1.1- 2.0); history of peripheral vascular interventions (OR 1.3, 95% CI 1.1- 1.5); bleeding disorders (OR 1.2, 95% CI 1.03- 1.4); emergency operation (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.4- 2.7); age above 80-years (OR 1.45, 95% CI 1.3- 1.7); tissue loss (OR 1.9, 95% CI 1.6- 2.3); extended pre-operative hospital stay (OR 2.2, 95% CI 1.8- 2.6); renal dialysis (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.3- 2.0)18. Prolonged LOS in the index admission is an independent risk factor for re-admission (p<0.0001). The increased LOS was a reflection of disease severity such as advanced peripheral arterial disease (PAD) and emergency department admission and occurrence of post-operative complications. Complications such as urinary tract infection, pneumonia, respiratory failure, congestive cardiac failure and more specifically, graft and wound infections, graft complications such as thrombus. 30-day re-admission was a reflection of underlying pathology such as advanced PAD, diabetes, chronic lung disease, renal failure, post-operative congestive cardiac failure and discharge to a rehabilitation type nursing facility19. A retrospective review of 6558 patients who underwent lower extremity bypass over a 3-year period found that the average LOS was statistically significantly shorter for those not re-admitted within 30-days, 5.5days compared to 8.3days for those were re-admitted within 30-days. 35% of the cohort were re-admitted within 30-days. The significant factors increasing LOS were increased disease severity and post-operative complications, emergency admission, advanced peripheral vascular disease (PVD), post-operative complications such as pneumonia, urinary tract infection, wound/graft infection, graft complications and if the patient was discharged to a nursing home i.e. not discharged to their own home. Factors that predicted 30-day re-admission were a reflection of the patients co-morbidities such as advanced PVD, diabetes, renal failure, chronic lung disease, post-operative heart failure and again, discharge to place other than their own home. Age was a protective factor for LOS but not for 30-day readmission20. A multi-centre review of LOS suggested a very weak link between increased LOS and 30-day re-admission after adjusting for age, gender, race, non-elective admission, co-morbidities, major post-operative complications and, discharge destination (Gonzalez)20.

Meyrs et al (2008)21 assessed the relationship between qualitative and quantitative measures of PVD. The disease was assessed by ankle-brachial pressure index (ABI) and in more detail on CT, MRI or invasive angiography. The claudication distance was assessed on a treadmill speed set at 0.67ms-1 (1.5mph) and at 10% gradient. The initial claudication distance was at the onset of claudication symptoms and the absolute claudication distance was the total distance walked before stopping due to pain. The walking speed was also assessed once patients had been familiarised with the use of the treadmill. The qualitative measures were carried out by using the validated, disease specific Walking Impairment Questionnaire (WIQ) that assesses pain, distance, walking and stair climbing, and, the Medical outcomes Study Short Form 36 (SF-36) Health Survey which assesses physical function, limitation due to physical health, limitation due to physical health, limitation due to emotional problems, energy, mental health, bodily pain, general health and social function. Control subjects were recruited on the basis their ABI was >0.9 such that there was a statistically significant difference between both groups for ABI. There were also statistically significant differences between the groups for their WIQ scores and on the SF-36, for physical function, physical limitations, bodily pain, social functioning and general health. The level of disease did not affect the outcomes on WIQ or SF-36. ABI had a significant correlation with the distance and speed components of WIQ but none of the components of SF-36 or the claudication distances. Yet claudication distance had significant correlation with many components of both WIQ and SF-36. Interestingly self-selected pace did not correlate with the qualitative measures. Ultimately, claudication distance, both initial and absolute, correlated with qualitative measures. Also, the WIQ was the reflection of actual ambulatory ability of patients with PAD.

An ERAS-type of critical pathway was proposed and assessed by Stanley et al (1998)22 for patients undergoing LEB. They acknowledged the heterogeneity of their patient cohort including emergency admissions and those patients transferred from other centres for vascular surgery input, similar to the model running in England and Wales currently. The model was based on a 5-day pathway and included many of the components of the current ERAS model such as removal of urethral catheter and encouragement of mobilisation on day 1 post-surgery. Crucially, the patient and family were educated about the pathway prior to elective surgery, as well as assessment of discharge needs with discharge planning commenced. The median LOS post-operatively in the post-pathway group was significantly reduced at median 6days (2-35) compared with 7days (2-29) pre-pathway (p=0.02). The anaesthetic route did not influence LOS in either pre- or post-pathway patients but the duration of epidural prolonged LOS. 55% of patients following the pathway were discharged to an intermediate care facility compared to 72% of pre- pathway patients were discharged directly home. The pathway did not affect the mortality and re-admission outcomes. Whilst age and body mass index (BMI) did not affect LOS, post-operative complication rates were increased in those with existing diabetes (30%) compared to those without diabetes (13%) and, those with cardiac disease (24%) compared to those without (15%). Patients with COPD, low pre-operative haematocrit or high pre-operative creatinine, also had prolonged LOS. Patients undergoing bypass for limb salvage had longer period of stay compared to those with claudication symptoms but also, the more distal anastomoses especially tibial vessels had longer hospital stay than more proximal anastomoses such as the popliteal artery. Again, those discharged to a facility other than their own home had a prolonged LOS. After adjustment, the independent factors associated with prolonged LOS were pre-operative anaemia, anastomosis to tibial vessels, pre-existing coronary artery disease and post-operative complications. Ultimately the pathway was not associated with a shorter LOS after adjusting for these factors. 8 of 69 pathway patients and 4 of 67 pre-pathway patients stayed beyond 14 days post-surgery. the reasons for their prolonged stay was existence of open ulcers necessitating debridement or amputation, suffering peri-operative MI, cardiac arrhythmia, ethanol withdrawal, respiratory failure caused by chronic pulmonary disease or large post-operative haematoma. Re-analysis of LOS after excluding the 12 patients with LOS greater than 14days, the only factor that was a predictor of longer LOS was diabetes. Another factor associated with increased length of stay and increased risk of post-operative wound complications is prolonged duration of bypass surgery. The duration of surgery was divided into quartiles of ≤149 minutes (6.3%), 150-192 minutes (9.0%), 193-248 minutes (10.1%) and, ≥249 minutes (13.9%) with p<0.01, a population of 2644 patients undergoing infra-inguinal bypass. The authors recognise there may be many confounders including system factors and surgeon factors involved but carrying out the operation in a reasonable time is an appropriate target to facilitate quality improvement (Tze-Woei)23.

Major lower limb amputation

Major lower limb amputation is indicated when revascularisation is no longer an option or amputation is expected to prolong life and even improve the patients quality of life7, 24- 25. A UK review of amputation data showed an average LOS of 32days (range, 7-67days). Early discharge planning is recommended but only 36.3% of vascular units had a dedicated vascular/ amputee discharge co-ordinator present. 25 Other aspects of planning for and managing patients pre- and post- amputation are assessment by a consultant vascular surgeon. 84% of trusts reported that all patients undergoing major amputations were preoperatively assessed by a consultant vascular surgeon. To facilitate discharge planning, 80% of vascular units reported patients were assessed by a rehabilitation physiotherapist, 61% reported patients were assessed by an occupational therapist and 25% reported preoperative assessments were available from a prosthetics service. 7

A review of Canadian data, 5342patients, 68% were male with a mean age of 67 +/- 13. The co-morbidities ranged from diabetes in 96%, hypertension in 33%, ischaemic heart disease in 18%, congestive cardiac failure in 10% and hyperlipidaemia in 5%. In 81% of admission, diabetic complications were commonest (81). Below knee amputation (BKA) was carried out in 65% of patients, followed by above knee amputation in 29%, the remainder having foot (4%), toe (1%) and ankle (1%) amputation. Factors statistically significantly associated with prolonged LOS, arbitrarily set at 7days were, amputation carried out by a general surgeon (OR 1.51, 95% CI 1.21- 1.87), an AKA (OR 0.71, 95% CI 0.61- 0.83), hypertension (OR 1.34, 95% CI 1.13- 1.58), ischaemic heart disease (OR 1.54, 95% CI 1.24- 1.91), congestive cardiac failure (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.86- 2.63) and re-amputation (OR 10.50, 95% CI 5.16- 21.35) within index admission. In-patient mortality was 9%. 65% of patients were discharged to a rehabilitation nursing facility and only 27% discharged home. Part of the explanation why those operated upon by a general surgeon is that the teams and possibly the hospitals where the surgery was carried out did not have the infrastructure set up for steering a complex discharge26.

Results

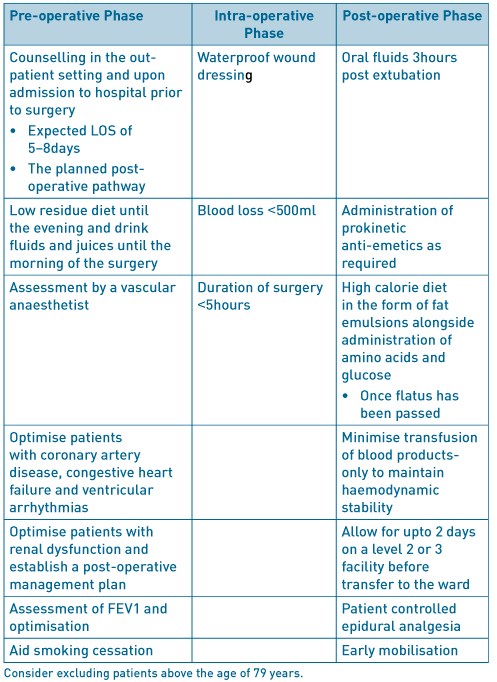

Open repair of AAA

Table 1. ERAS factors to consider in open AAA.

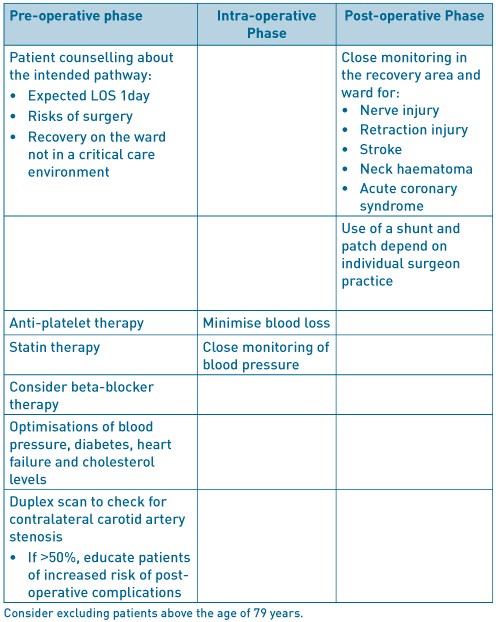

Carotid endarterectomy

Table 2. ERAS factors to consider in carotid endarterectomy.

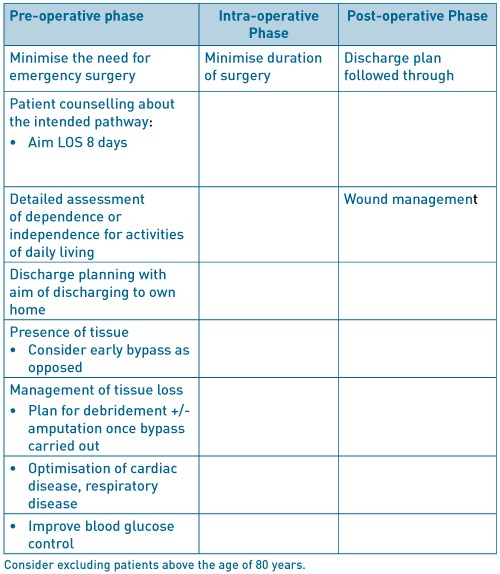

Infra-inguinal lower limb bypass

Table 3. ERAS factors to consider in infra-inguinal lower limb bypass

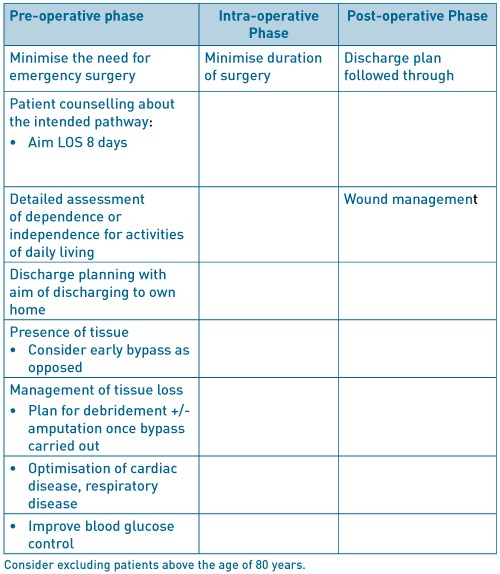

Major lower limb amputation

Table 4. ERAS factors to consider in major lower limb amputation.

As can be seen Tables 1-4 above, there are common themes present in all the major vascular surgery interventions. Primarily, optimisation of the major co-morbidities and pre-operative assessment by an anaesthetist specialising in vascular surgery. Cardio-pulmonary exercise testing is now widely being used in the assessment of patients prior to elective vascular surgery7. Also, factors such as smoking cessation therapy introduced 4-6weeks prior to surgery has been shown to reduce post-operative cardiac complications and LOS. Initial reduction of lung secretions and improving lung function can be augmented by an exercise program. The use of statins commenced 30-days prior to surgery and continued indefinitely, improve cardiac morbidity and mortality. The use of beta-blocker agents particularly bisoprolol, commenced 30-days prior to surgery, in patients with the highest and intermediate cardiovascular risk27.

Conclusions

Although ERAS in its current form may not be applicable to non-cardiac vascular surgery, with modifications for the different types of surgery, it can be seen to be useful to not only reduce length of stay but improve patient progress and well- being. In-depth assessment is required for each major intervention.

References

- Kehlet H. Multimodal approach to postoperative recovery. Curr Opin Crit Care 2009;15:355-358.

- Kehlet H. Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS): good for now, but what about the future? Can J Anesth 2015;62:99-104.

- Tatsuishi W, Kohri T, Kodera K, Asano R, Kataoka G, Kubota S, Nakano K. Usefulness of an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol for perioperative management following open repair of an abdominal aortic aneurysm. Surg Today 2012;42:1195-1200.

- UK Small Aneurysm Trial Participants. Length of Hospital Stay following Elective Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Repair. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 1998;16:185-191.

- Chang JK, Calligro KD, Lombardi JP, Dougherty MJ. Factors that predict prolonged length of stay after aortic surgery. J Vasc Surg 2003;38:335-339.

- Huber TS, Wang JG, Derrow AE, Dame DA, Ozaki CK, Zelenock GB, Flynn TC, Seeger JM. Experience in the United States with intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair. J Vasc Surg 2001;33:304-311.

- Waton S, Johal A, Heikkila K, Cromwell D, Loftus National Vascular Registry: 2015 Annual Report. London: The Royal College of Surgeons of England, November 2015.

- Muehling B, Schelzig H, Steffen P, Meierhenrich R, Sunder-Plassmann L, Orend KH. A prospective randomized trial comparing traditional and fast-track patient care in elective open infra-renal aneurysm repair. World J Surg 2009;33(3):577-585.

- Gurgel SJT, Dib R El, Nascimento P Do. Enhanced Recovery after Elective open Surgical Repair of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm: A Complementary Overview through a Poole Analysis of Proportions from Case Series Studies. PLoS ONE 9(6): e98006. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.009800.

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Transient Ischaemic Attack Pathway https://pathways.nice.org.uk/pathways/stroke/transient-ischaemic-attack#content=view-node%3Anodes-assessing-and-managing-carotid-stenosis accessed 15/07/2016.

- Sheehan MK, Baker WH, Litgooy FN, Mansour A, Kang SS. Timing of postcarotid complications; A guide to safe discharge planning. J Vasc Surg 2001;34:13-16.

- Angevine PD, Choudri TF, Huang J, Quest DO, Solomon RA, Mohr JP, Heyer EJ, Connolly S. Significant Reductions in Length of Stay After Carotid Endarterectomy Can Be Safely Accomplished Without Modifying Either Anaesthetic Technique or Postoperative ICU Monitoring. Stroke 1999;30:2341-2346.

- Hernandez N, Salles- Cunha SX, Daoud YA, Dosick SM, Whalen RC, Pigott JP, Siewert AJ, Russell TE, Beebe HG. Factors related to short length of stay after carotid endarterectomy. Vasc Endovascular Surg 2002;36(6):425-437

- Roddy SP, Estes JM, Kwoun MO, O’Donnell TF, Mackey WC. Factors predicting prolonged length of stay after carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 2000;32:550-554.

- Reed AB, Gaccione P, Belkin M, Donaldson MC, Mannick JA, Whittemore AD, Conte MS. Preoperative risk factors for carotid endarterectomy: Defining the patient at high risk. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1191-1199.

- Halm EA, Tuhrim S, Wang JJ, Rockman C, Riles TS, Chassin MR. Risk Factors for Perioperative Death and Stroke After Carotid Endarterectomy. Stroke 2009;40:221-229.

- Riles TS, Imparato AM, Jacobwitz GR, Lamparello PJ, Gianglo G, Adelman MA, Landis R. The cause of perioperative stroke after carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg 1994;19:206-216.

- Siracuse JJ, Jones DW, Gill HL, Graham A, Schneider DB, bush HL, Karwowski Connolly PH, Meltzer AJ. Lower Extremity Bypass for Critical Limb Ischaemia- Predicting Extended Length of Stay. J Vasc Surg 2013;58(4):1151.

- Damrauer SM, Gaffey AC, Smith DeBord, Fairman RM, Nguyen LL. Comparison of risk factors for length of stay and readmission following lower limb bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg 2015;62(5):1192-1200.

- Gonzalez AA, Mell MW, Osborne NH. Reducing Length of Stay Is Not Associated With Increased Readmission Rates Following Lower Extremity Arterial Bypass. J Vasc Surg 2015;61(6):189S.

- Meyers SA, Johanning JM, Stergion N, Lynch TG, Longo GM, Pipnos II. Claudication distance and the Walking Impairment Questionnaire best describe the ambulatory limitations in patients with symptomatic peripheral arterial disease. J Vasc Surg 2008;47:550-550.

- Stanley AC, Barry M, Scott TE, LaMorte WW, Woodson J, O.Menzoian J. Impact of a critical pathway on postoperative length of stay and outcomes after infrainguinal bypass. J Vasc Surg 1998;27:1056-65.

- Tze-Woei T, Kalish JA, Hamburg NM. Shorter Duration of Femoral-Popliteal Bypass Is Associated With decreased Surgical Site Infection and Shorter Hospital Stay. J Am Coll Surg 2012;215:512-518.

- The Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Quality improvement framework for major amputation surgery. 2010. Vascular Society of Great Britain and Ireland. http://www.vascularsociety.org. uk/news-and-press/2010/47-quality-improvementframework-for-major-amputation-surgery-.html

- National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcomes and Deaths. Lower Limb Amputation: Working Together 2014. London: NCEPOD, 2014.

- Kayssi A, de Mestrel C, Forbes TL, Roche- Nagle G. A Canadian population-based description of the indications for lower-extremity amputations and outcomes. Can J Surg 2016;59(2):99-106.

- Moll FL, Powell JT, Fraedrich G, Verzini F, Haulon S, Waltham M, van Herwaarden JA, Holt PJE, van Keulen JW, Ranter B, Schlosser FJV, Setacci F, Ricco JB. Management of Abdominal Aortic Aneurysms Clinical Practice Guidelines of the European Society for Vascular Surgery. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2011; 41:S1-S58.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6177/274-dhillon.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1189#collapse5

Authors: Mazhar H. Raja1, Louise Dunphy2, Douglas McWhinnie3, Kian Chin1, Simon Ray-Chaudhuri1

- Consultant General Surgeon, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

- Core Surgical Trainee, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

- Consultant General and Vascular Surgery. Professor of Clinical Education, University of Buckingham, Milton Keynes University Hospital.

Correspondence: Department of General Surgery, Standing Way, Eaglestone, Milton Keynes. MK6 5LD. Tel: 01908 6600033. Email: dunphylmb@gmail.com.

Keywords: perioperative, voiding related delays, urinary retention.

Abstract

Introduction: Postoperative urinary retention [POUR] is the inability to pass urine following surgery despite a painful, palpable or percussible bladder. Postoperative urinary retention has a multifactorial aetiology and is common after anaesthesia and surgery, with a reported incidence of between 5-70%. The ability to void has always been considered as one of the discharge criteria for elective day case surgical patients. POUR can lead to delayed hospital discharges with an overnight stay, resulting in an increased burden on staff, inconvenience to patients as well as financial implications.

Aim: To analyse the perioperative risk factors that contribute to the development of POUR. To determine whether our discharge protocol implemented in 2015 has led to more efficient but safe patient discharges for elective day case surgical patients.

Methods: A 6-month retrospective review of general surgery day case operations [96 cases] performed by a single surgical team from October 1st2016 until March 31st 2017. Data was retrieved from the electronic patient records. The incidence of POUR in both high and low risk groups was assessed We audited compliance with our POUR protocol and the effectiveness of its implementation.

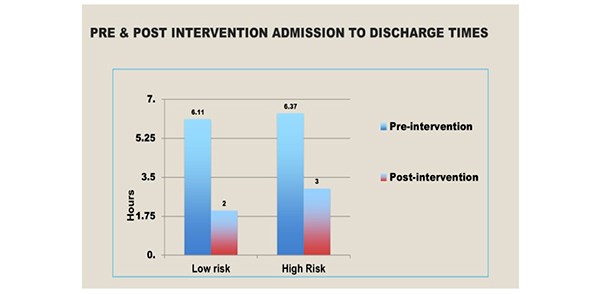

Results: All cases were performed under General Anaesthesia by a single surgical team. POUR occurred in 4.3% of the elective general surgical day cases. The incidence in low risk groups was 2.3% and 5.6% in the high-risk group. This audit has demonstrated that the post-protocol admission to discharge times have decreased significantly, from an average of 397 minutes to 115 minutes for low risk patients and 160 minutes for the high-risk groups.

Conclusion: The incidence of POUR in patients undergoing day surgery was much lower than expected, we advocate our local protocol to enable more efficient patient discharges whilst ensuring patient safety.

Keywords: postoperative urinary retention [POUR], void, catheter.

Introduction

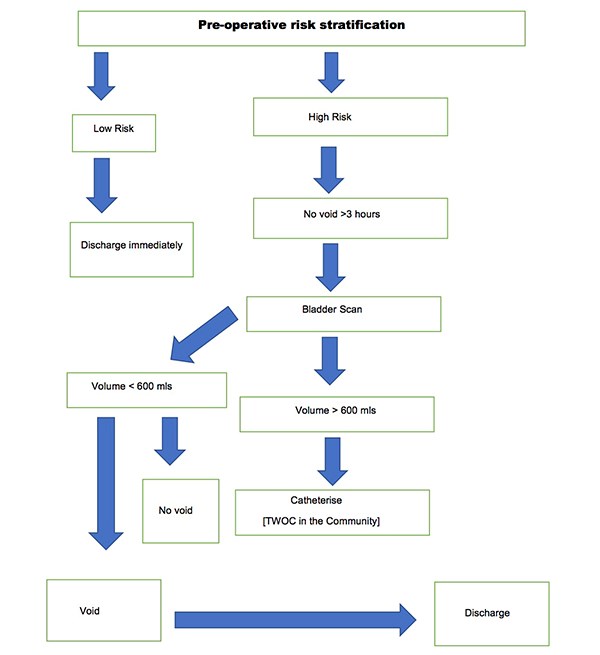

Urinary retention is a common complication of surgery and anaesthesia, increased in patients with advancing age following pelvic and anorectal surgeries. Other risk factors for the development of POUR include epidural and spinal anaesthetics and analgesics administered via the epidural or intra thecal route. It is imperative that POUR is identified and managed appropriately. Recommendations for urinary catheterisation in the postoperative period varies widely. It is also governed by local policies. Untreated prolonged POUR is associated with adverse events such as bladder distension, which can result in long-term bladder dysfunction especially in the elderly. In 2015, a voiding discharge protocol for general surgical patients undergoing day surgery based on a retrospective cohort study evaluating outcomes in 616 patients between October 2014 and February 2015 was established in our Department. Data was analysed to assess which patients required an overnight stay and the incidence of POUR in high and low risk groups. An algorithm was developed to guide discharge in low risk groups. [Figure 1] The implementation and use of this protocol was then audited. POUR occurred in 2.6% of the general surgical day cases. The incidence in the low risk groups was 1.28% whilst it was 4% in the high-risk group. Post-protocol admission to discharge times decreased significantly from an average of 397 minutes to 170 minutes for low risk patients and 160 minutes in the high-risk group. There were no re-admissions. Therefore, the authors performed a retrospective study to determine adherence to the protocol and to establish its impact on effective day-case discharges.

Figure 1. Discharge Algorithm for both high and low risk patients.

Aim

To analyse the perioperative risk factors that contribute to POUR and to determine whether the discharge protocol implemented in 2015 has led to more efficient but safe patient discharges.

Method

A six-month retrospective review of 96 elective general day case operations performed by a single surgical team at Milton Keynes University Hospital from October 1st 2016 until March 31st 2017. Data was retrieved from the electronic patient records. The incidence of POUR in both high and low risk groups was assessed. In our study, high risk groups included men aged over 50 years undergoing inguinal hernia repair or anorectal surgery eg. haemorrhoidectomy. Prostatic pathology such as benign prostatic hyperplasia, cancer and a previous history of urinary retention were documented. In addition, co-morbidities such as diabetes and neurological disease, for example, stroke, multiple sclerosis and parkinson’s disease were noted. Peri-operative medications were reviewed and the use of sympathomimetics, anti-cholinergics, alpha and beta-blockers were recorded. Intra-operative risk factors for the development of POUR were reviewed, including the volume of intravenous fluids administered during anorectal surgery as well as the duration of surgery. Anaesthetic charts were assessed to determine if spinal or epidural anaesthesia was administered. Postoperative risk factors including the use of sedative medications and postoperative analgesia such as a continuous epidural infusion of patient controlled analgesia were noted. Low risk patients for POUR were discharged immediately. Similarly, if high risk patients successfully voided, they were discharged home. High risk patients failing to void three hours postoperatively received a bladder scan. Failure to void, with a bladder volume >600mls required a urinary catheter, followed by a trial without a catheter in the community. Compliance with our POUR Protocol was assessed.

Results

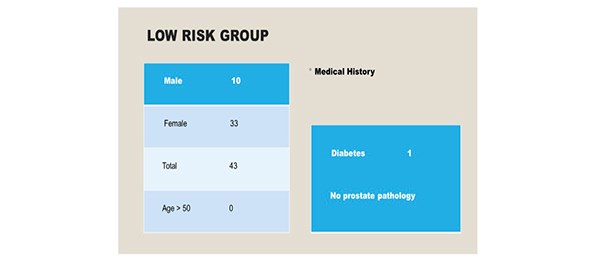

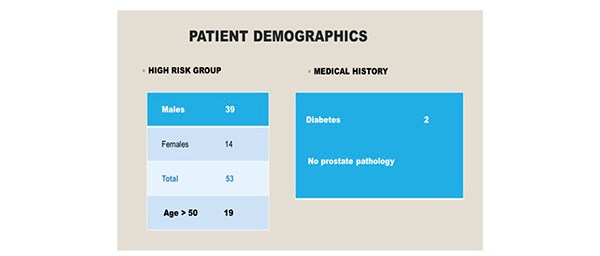

Ninety-six patients were included in the study over a six-month period. There were 43 patients [10 males, 33 females] in the low risk group. All individuals were aged less than 50 years. [Figure 2] Co-morbidities included one patient with type two diabetes and there were no individuals with a significant urological history. All patients underwent General Anaesthesia, induced with propofol and maintained with sevoflurane. Epidural or spinal anaesthesia was not required in this cohort. 53 patients [males 39, females 14] were identified as high risk for the development of POUR. In the high- risk group, 19 individuals were aged above 50 years. Two patients were diabetic and no patients had a urological history. [Figure 3]

Figure 2. 43 individuals were identified as low risk for the development of POUR.

Figure 3. 53 individuals were identified as high-risk for the development of POUR.

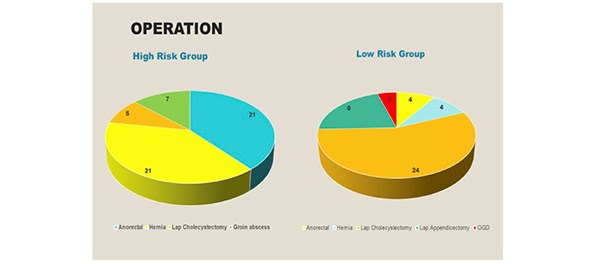

In the high-risk group, the following elective day case operations were performed: anorectal surgery [21], hernia repair [21], laparoscopic cholecystectomy [5] and drainage of a groin abscess [7]. In the low-risk group, 4 anorectal operations were performed, followed by hernia repair [4], laparoscopic cholecystectomy [21], laparoscopic appendicectomy [9] and an OGD [4]. [Figure 4]

Figure 4. The operations performed in both the high and low risk groups.

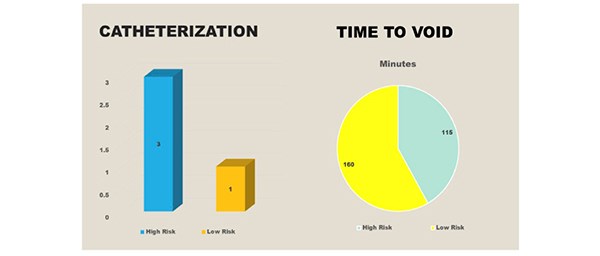

Urinary catheterisation was required for three individuals in the high-risk group due to an inability to void, despite an ultrasound scan confirming >600mls in the bladder. In the low-risk group, one catheter was inserted due to a painful, palpable bladder. [Figure 5] All cases required intermittent in and out catheterisation. The average time to void in the high-risk group was 160 minutes and 115 minutes in the low risk group.

Figure 5. Three catheters were inserted in the high-risk group and the average time to void was 160 minutes. One catheter was inserted in the low risk group and the average time to void was 115 minutes.

Following implementation of the POUR discharge protocol in 2015 there has been a significant reduction in the admission to discharge times in both the high and low risk groups. [Figure 6]

Figure 6. The pre and post intervention admission to discharge times.

Conclusion

Following our successful retrospective cohort study which proved that the incidence of POUR in patients undergoing day surgery was much lower than expected, we advocate our local protocol to enable more efficient patient discharges whilst ensuring patient safety. Our protocol has shown to significantly reduce time spent in the day surgery unit therefore saving bed-hours and avoiding patient inconvenience. The authors plan to continue collecting data and ensure compliance with the protocol.

Discussion

Postoperative urinary retention [POUR], defined by Baldini as the inability to void with a full bladder is a common complication of surgery and anaesthesia1. It has a reported incidence of between 5-70%, although the true incidence is unknown due to the lack of defining criteria. Firstly, it is important to understand the physiology of micturition. The detrusor muscle forms the body of the bladder and the neck has an internal layer of smooth muscle surrounding the internal meatus of the bladder, known as the internal urethral sphincter1. Multiple afferent and efferent neural pathways, reflexes, central and peripheral neurotransmitters are involved in the control of micturition. The adult bladder has a urinary capacity of 400-600mls. Two phases, the storage and emptying phase can be distinguished during micturition. At 150mls, the first urge to void is felt and the tension receptors are activated at 300mls leading to parasympathetic neuron activation and contraction of the detrusor muscle. When the intravesical pressure reaches the voiding threshold, the detrusor contractions increase in intensity, frequency and duration, allowing the bladder to empty.

The risk factors for developing POUR include advancing age, with men aged over 70 years appearing to have a higher incidence. Indeed, age related progressive neuronal degeneration leads to bladder dysfunction2. Mechanical obstruction of the urinary outflow tract causes urinary retention in the postoperative period. In addition, altered neural control of the bladder as well as the detrusor mechanism is another cause3. Other pre-operative risk factors include co-morbidities such as neurological disease, diabetes mellitus as well as the use of pharmacological agents such as anti- cholinergics, sympathomimetics, alpha and beta blockers. The type of surgery performed is also significant with an increased prevalence reported in abdominal, pelvic and orthopaedic surgery. In patients undergoing anorectal surgery, a high incidence of POUR is observed. This is caused by injury to the pelvic nerves and an increase in the tone of the internal sphincter caused by the pain evoked reflex4. A urological history including obstructive uropathic symptoms or prostatic enlargement are other independent risk factors. Furthermore, general anaesthetic agents and opioid analgesics cause bladder atony by interfering with the autonomic nervous system. Propofol impairs the micturition reflex and reduces detrusor contractility4. In addition, spinal anaesthesia has an effect on the pontine micturition centre and acts on the sacral spinal cord segments S2-S4. The use of long-acting local anaesthetics is related to a higher incidence of POUR5. The use of patient-controlled analgesia also increases the probability of urinary retention. Opioids increase the tone and range of contractions of the urinary sphincter, but diminish contractions of the urethra making spontaneous urination difficult6. As well as this, the use of fentanyl makes it difficult for individuals to void spontaneously because it inhibits the reflexes below the level of the epidural lumbosacral puncture. Other predictive factors of early postoperative urinary retention include intra-operative risk factors such as longer duration of surgery and administration of >750mls intra-venous fluids. Excessive infusion of intra-venous fluids can lead to overdistension of the bladder especially in patients under spinal anaesthesia4.