Dave Bunting

In this first edition of JODS 2020, I am pleased to announce that abstract submission for the Annual Conference being held at the Cardiff City Hall on 25th and 26th June is open. Please submit your abstract as soon as possible via the link below:

Conference Abstract Submission

https://app.oxfordabstracts.com/login?redirect=/stages/1625/submissions/new

If you are considering submitting an abstract or attending the conference, I would like to remind you at this stage to book your study leave with your trust for the Conference as soon as possible.

Registration for the Conference is also open. Please take advantage of the early bird rates available until 1st May:

Annual Conference Registration

https://app.oxfordabstracts.com/login?redirect=/events/1421/delegate-registration

Free Conference Registration!

Please note that this year BADS will be offering a free conference registration place for one nurse or allied health professional to any Hospitals/Trusts booking 10 two-day conference places for their staff.

Invitation to Council

BADS will soon be advertising for positions on Council. This is a fantastic opportunity for BADS members to become more involved with the association and I would strongly encourage any interested members to apply. Details will be posted on the BADS website in early March.

This year BADS again plans to co-host several national and regional meetings in association with external organisations such as Health Care Conferences UK (HCUK):

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Breast Surgery as Day Surgery will be held on Thursday 27th February at the W1 De Vere Conference Centre, London.

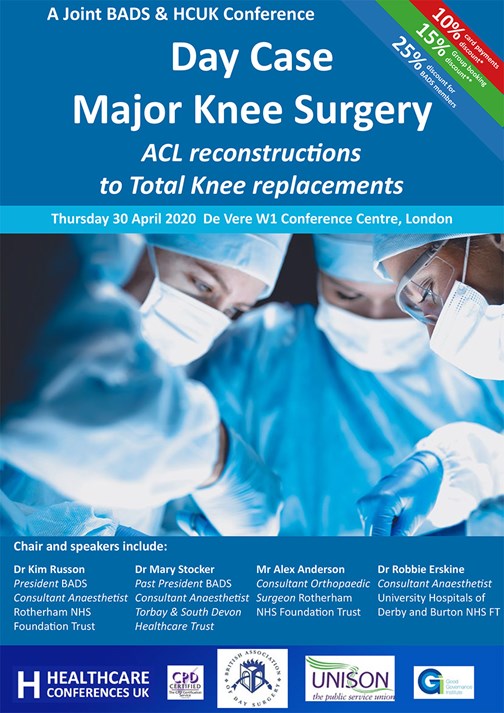

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Day Case Major Knee Surgery will be held on Thursday 30th April at the De Vere W1 Conference Centre, London.

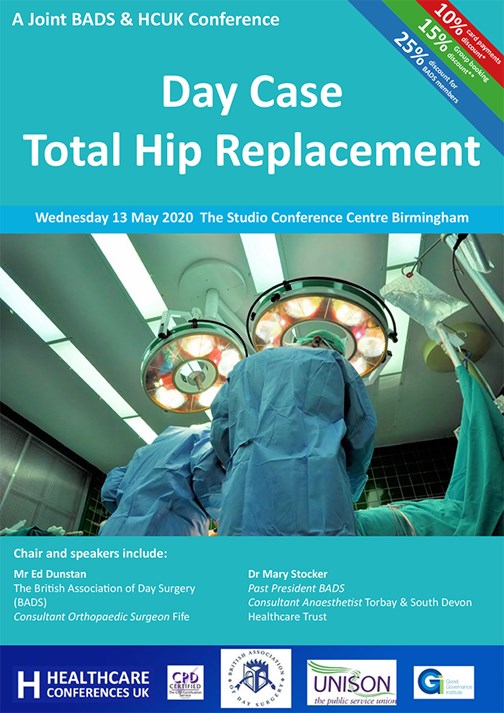

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Day Case Total Hip Replacement will be held on Wednesday 13th May at The Studio Conference Centre, Birmingham.

Further details of all the above conferences can be found in this edition of JODS.

Original papers in this edition of JODS include a comparison of Intra-capsular Coblation Tonsillectomy vs. traditional Dissection Tonsillectomy; an audit of One The Day Theatre Cancellations and a quality improvement project assessing the benefits of introducing a patient information video as part of the informed consent process for laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

The importance of day surgery in the national political agenda has been emphasised again through work done by Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT). Significant variation in day surgery performance has been highlight across the country and several STPs are undertaking initiatives to reduce variation and increase the proportion of patients being treated on a day case basis.

Finally, I would like to welcome Andrei Tanase to the BADS Council as our new Surgical Trainee Representative. Andrew is the Severn Deanery Representative for the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) and his full biography can be found in this edition of JODS.

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse0

Kim Russon

Happy New Year to you all! I hope you are all coping with the workload and your Trusts are all managing to maintain your day surgery pathway during these times of winter pressures. It seems to have been worse this year with my Trust being on top alert more frequently than last year. However, our day surgery unit (DSU) continues to be busy because my Trust’s winter plan includes that only urgent inpatient elective surgery is listed for the first few weeks of the year and in fact we have increased the number of urgent/ emergency general surgical abscesses and ambulatory orthopaedic trauma that is going through our DSU. I hope your hospital acknowledges the importance of protecting your day surgery pathway.

I was delighted to be invited to the launch of the Ear Nose & Throat (ENT) Get it Right First Time (GiRFT) report last month where the Number one recommendation was to: Increase the use of day case across ENT. Mr Andrew Marshall, GiRFT national lead clinical lead for ENT surgery is a surgeon at Nottingham University Hospitals. He reported that they found a wide variation of day case rates across England which could not be explained by case mix. The identified benefits of a GiRFT review can be viewed as an opportunity for individuals or Trusts to review what peers are doing and challenge your own current practice, therefore it may prompt changes to clinical practice and open up procurement opportunities.

We had a very successful combined BADS/HCUK Day case General Surgery conference in Birmingham on 21st January 2020. We learned about the challenges and opportunities involved in setting up surgical Same Day Emergency Care (SDEC) units from the SDEC national lead Mr Arin Saha. An update from GiRFT Peri-operative medicine lead Dr Chris Snowden explained how looking at the variation in pathways of care that exist across the UK can help effect change in day case pathways for the future. There were also excellent talks about improving day case Laparoscopic cholecystectomy rates and pushing the boundaries with day case reflux surgery and 23hour stay colorectal surgery.

Our BADS Conference team have created a fantastic programme for you in Cardiff this year. The provisional programme will be released next month and includes topics on how to do day case foot and ankle surgery; mastectomy; vaginal surgery; pyeloplasty; repair of fractured mandibles and zygomas. There will be workshops on enabling change in your day case unit, ensuring good wellbeing and optimising pre-operative assessment. There is always a wealth of shared information from centres around the country from the submitted abstracts so I urge you to please submit your abstracts soon (Abstract submission closes Friday 17th April), book your leave and register for the BADS conference 25th - 26th June in Cardiff. I look forward to seeing you there.

I would also like to invite anyone interested in progressing day surgery to please consider joining BADS council. Day surgery is so important and there is so much that can be done to help increase day case rates across the country in so many different specialities. Members of BADS council have been invited to speak at a number of specialist society meetings (Eg. Association of Breast Surgeons, British Orthopaedic Association) and are involved in a number of national workstreams (Eg. Best practice tariffs (BPT), Model Hospital). We already have a great multidisciplinary BADS council but we have some vacancies being advertised next month, so please consider applying and you have any queries don’t hesitate to contact me via president@bads.co.uk

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34957/301-president.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse1

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34959/asm-2020-flyer.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse2

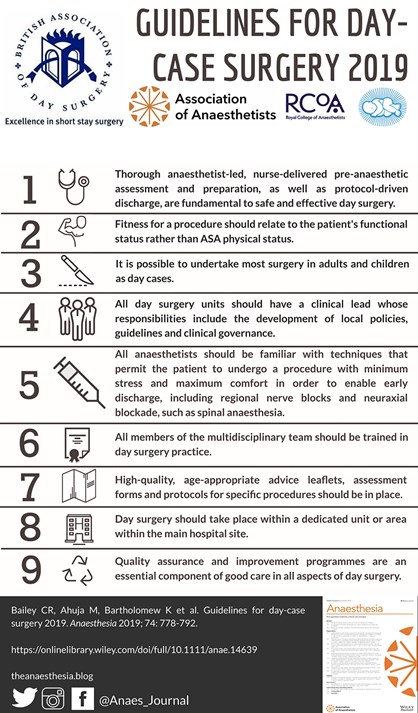

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34942/infographic.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse4

N Keates* & J Rainsbury**

*ST3, ENT, Derriford Hospital, Derriford Road, Plymouth, UK

**Consultant, ENT, Derriford Hospital, Derriford Road, Plymouth, UK

Corresponding Author

Natasha Keates Email: n.keates@nhs.net

Abstract

Aims: The aim was to complete a first cycle audit looking at the complication rate for the two procedures and determine whether the new procedure (Intra-capsular Coblation Tonsillectomy) was as safe or safer when compared to current standard management, and as such should be preferable.

Methods: Cases of Coblation procedures for one surgeon were found via coding and the complications determined via E-discharge or patient notes if required. The most recent equal number of dissection tonsillectomies for the same surgeon were also reviewed. We reviewed cases from October 2016 to November 2018. Cases of both procedures were for paediatric patients with an indication of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) for tonsillectomy. 52 cases of coblation tonsillectomy were found so 104 were reviewed in total.

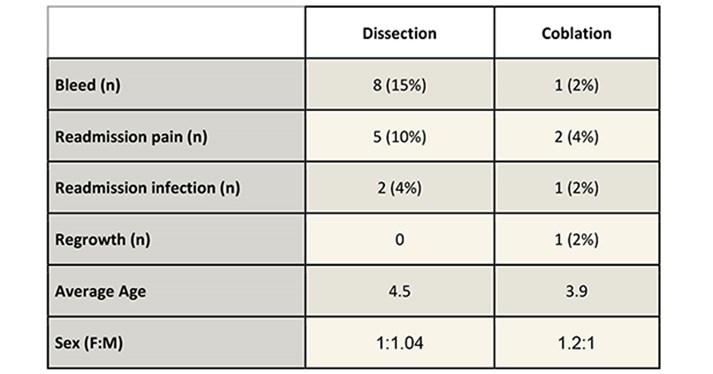

Results: There were 8 bleeds vs 1 for coblation, 5 readmissions for pain vs 2 for coblation, 2 readmissions for infection vs 1 for coblation. The coblation category did show 1 case of tonsil regrowth which was treated with subsequent dissection tonsillectomy.

Dissection: coblation had an average age of 4.5 vs 3.9 respectively. Female to Male ratio was 1:104 vs 1.2:1 for coblation.

Conclusions: Intra-capsular coblation tonsillectomy in this patient group is safer than dissection tonsillectomy with the added possible complication of tonsil regrowth. The complication profile for coblation is reduced which is in the interest of patients and their safety. It also reduced the readmission rate which has ongoing positive cost implications for the department.

Introduction

Tonsillectomy is a common procedure performed for several indications including recurrent tonsillitis, obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) and occasionally for histological biopsies. It is generally considered to be a safe procedure but with a documented risk of post op bleeds, and an associated return to theatre rate. It is also considered to be a painful procedure post op and patients are generally recommended to take 2 weeks off school or work’ (1).

Evelina have published a case series of intracapsular coblation tonsillectomies, reporting a reduced complication profile in comparison to the more traditional dissection tonsillectomy. They have also reported reduced post op pain and earlier return to school rates1.

Intracapsular tonsillectomies have been offered within Derriford by one consultant for paediatric patients with OSA for the last couple of years.

The aim of this first cycle audit was to compare the current complication profile of the unit’s standard treatment (Dissection tonsillectomy) and compare it to a case series of a new treatment (intracapsular coblation tonsillectomy). So, the treatment with the safer complication profile can be offered to paediatric patients with OSA.

The audit standards were set as the departments current practice. The current audited bleed post tonsillectomy bleed rate, readmission rate and tonsillar regrowth as reported within this audit.

The bleed rate has been noted by the department to be higher than the reported national average. This is however in keeping with the regionally reported bleed rate. Comparison have been made between technique and operator (including grade) with no culpable variation noted. This has contributed to the interest in coblation tonsillectomy with its possible lower complication profile to reduce the rate of post op bleeds/complications and provide safer care for our patients.

Methods

The coding office provided a list of all tonsillectomies regardless of procedure between October 2016 and November 2018 on a single consultant’s theatre list. These dates were chosen to ensure a reasonably sized case series. Cases of coblation were hand searched from the coding list, 52 were found in total. Unclearly coded cases were reviewed with notes (12 in total) but no further coblation cases were found. As this consultant doesn’t perform extra-capsular coblation tonsillectomies we were able to clearly confirm the cases via coding and the online discharge summaries.

This list of patients was then matched by the most recent equal number of dissection tonsillectomies performed on this consultant list.

Inclusion criteria for both procedures were for paediatric patients with an indication of obstructive sleep apnoea (OSA) alone for tonsillectomy. Although trainees will have also performed some of these cases, we did not limit the audit to one operator in order to reflect a real-life complication profile from a multi-operator theatre list. All patients included were from one consultant’s practice.

51 cases of coblation tonsillectomy were found so 102 cases of tonsillectomy were reviewed in total. Statistical analysis was developed using SPSS version 25.

Results

.

Limitations

The reduction in admissions due to pain and infection were not statistically significant (Chi Squared test). The increase in regrowth with coblation was also not statistically significant. The reduction in post op bleeds however was shown to be statistically significant (Chi Squared test) with a P value of 0.015. The groups were compared with an un-paired T-Test which showed that there was no significant difference in the mean for Gender or age.

The groups were not matched but statistical analysis shows no significant difference between the age or gender of the groups. Both groups of patients were from a single consultant’s practice and so reflect the standard variation seen in a consultant’s patient population with regards to proportion performed under supervision by trainees.

Discussion

As is demonstrated from the results table we found that Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy has a safer complication profile with a statistically significant reduction in post op bleeds. The reduction in re-admission rates was not statistically significant but this may be limited by sample size. The coblation group also showed an acceptably low regrowth rate which is in line with the Evelina case series published (2).

It is important to note that the post tonsillectomy bleeds were universally secondary bleeds with only one requiring intervention. The patient requiring intervention was from the dissection group.

The audit concludes that the complication profile for intracapsular tonsillectomy is reduced compared to dissection tonsillectomy in paediatric patients with obstructive sleep apnoea, when performed by a competent surgeon. With a 13% reduction in post op bleeds and a 7% reduction in readmission due to pain or infection. There is a 2% risk of regrowth in the intracapsular group but this is in line with other studies findings and is acceptable in comparison to the overall risk reduction associated with this procedure.

Following local departmental presentation of this audit the reduced complication profile was considered persuasive and so the other consultants who operate on this patient group have agreed to engage in education and training in order to provide this treatment to their patients.

The outcome will then be re-audited as a unit to see if it has had a wider effect on the unit’s complication rate as a whole.

References

- Lowe D, van der Meulen J, Cromwell D, et al. Key messages from the National Prospective Tonsillectomy Audit. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(4):717‐

- Hoey, AW, Foden, NM, Hadjisymeou Andreou, S, Noonan, F, Chowdhury, AK, Greig, SR et al. Coblation intracapsular tonsillectomy (tonsillotomy) in children: a prospective study of 500 consecutive cases with long-term follow-up. Clin Otolaryngol 2017;42:1211–17

(Click on image to go to the company website.)

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34941/301-keates.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse5

Mehdi S. N. Raza Consultant Surgeon¹

Sagar Gurung resident surgical officer, Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup

Himalaya Gurung resident surgical officer, Queen Mary’s Hospital, Sidcup

Department of Surgery, Dartford and Gravesham NHS trust, Kent

Corresponding Author: Mr. Mehdi S. N. Raza Surgical Directorate, Darenth Wood Rd, Dartford DA2 8DA Email: mehdiraza@nhs.net

Source of funding: author for video/audit department

Keywords: Informed consent, Laparoscopic cholecystectomy, Audio-visual aids

Abstract

Background: The current time requires clinicians to improve the health education we provide in clinics. Individuals undergoing major surgery should be well informed and provided with enough time to make a decision.

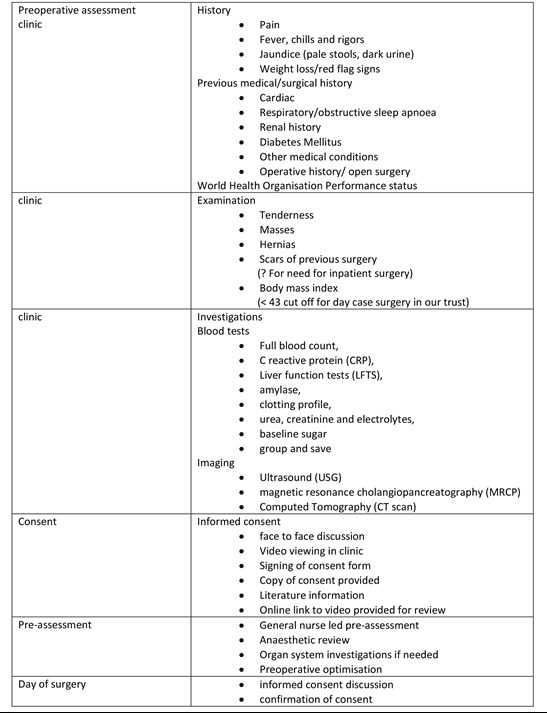

Methods: This is a closed loop audit aimed at improving the informed consent process for day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy by audio-visual aids in clinics. We asked fifty patients attending clinics for consideration for a day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy what they thought of the standard informed consent by filling a simple questionnaire after a clinic visit. After reviewing the results, we realised the process of consenting needs to improve. We then improved the informed consent procedure by adding an informative video for clinics and developed a new information leaflet. Thirty-five patients gave their feedback on the new consenting process by filling in a simple questionnaire at the end of their clinic consultation.

Results: A survey assessed our current consenting process. Out of the 50 returned questionnaires returned, thirteen patients did not remember any of the conversation in clinic. Five patients were consented on the day of the surgery. In conclusion, individuals agreed audio-visual information would be beneficial for the consenting procedure in clinic.

We organised a four-minute animated video and a new information leaflet to improve our informed consent procedure. Information included was about the perioperative journey and specific anatomy and risks of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We received excellent feedback from 35 patients. We have applied this change to the current day case practice.

Conclusion: Audio-visual aids help in providing patients with good quality information for a well-informed mutual agreement about major surgical procedures. The author finds audio visual aids are useful for discussing major surgical procedures in the clinic and does not affect the amount of time spent with each patient.

Introduction

Gallbladder surgery has evolved through a series of interesting events over more than a century. After the first ever-recorded cholecystectomy performed in 1882, little did we know that it would become one of the most performed operations worldwide? The only procedures performed prior to this were drainage of abscesses, removal of stones or management of cholecystic fistulas.(Sparkman 1982)

It was 103 years later that the first laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed by Professor Dr Med Erich Mühe of Böblingen, Germany on September 12, 1985. He eventually received recognition of his work in 1995 with The German Surgical Society Anniversary Award. He can be given credit for inventing numerous instruments used in a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.(Reynolds 2001)

Despite technological advancements throughout the last 3 decades, the procedure has not changed much from the one performed by Professor Muhe in 1985. Some trusts are performing more of these procedures as ‘one stop’ care in day-case centres, by setting up pathways and streamlining the referral and gallbladder imaging process. Despite it being one of the commonest day case procedures, patients often are referred from clinicians with limited surgical experience of the procedure. This is where audio-visual education in clinics can be beneficial. (Clarke et al. 2011)

Our initial audit was a survey of the current process of informed consent for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. We made improvements in consenting with audio-visual aids in the form of a video, literature and signing a written consent in clinic. It is common knowledge that more audio-visual aids improve health education and understanding shown in randomised controlled trials discussed below. We found numerous weaknesses in the quality of information they provided and decided to produce our own information video. We will provide the link of the consent video to access through the hospital website for the benefit of patients and clinicians.

Methods and Patients

Surgeons performing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy may only see the patients on the day of the procedure due to numerous reasons. This is despite our trust guidelines requiring us to consent patients in clinic. Informed consent is the mutual agreement between the clinician and the individual for a surgical procedure after thorough discussion of the options, the risks and the perioperative pathway of surgery. We know that despite thousands of such day case procedures progress uneventfully, complications still happen. A thorough and high-quality consenting process discussing general and specific gallbladder surgery risks is essential.

We discussed the audit proposal within our audit department on the 29th of June 2017 and produced a scope document and a simple questionnaire.

The individuals included in the survey were booked from across both hospital sites. No emergency cases were included for this audit. The initial survey over three months took place in Queen Mary’s Hospital (one of our two sites) for ease of completion of surveys. We asked individuals specific questions on components of the informed consent of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy like need for illustrative basic anatomy and more visual information of risks of surgery. The National Institute of Clinic Excellence (NICE) guidelines outline the best medical practice for informed consent. We reviewed the patient information leaflets in our trust and compared them with local hospital trusts. We received 50 questionnaires filled in after standard consultation for a laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Results

The results revealed that all the patients were informed of the options, risks and benefits of the procedure at clinic appointment. Patients were provided information leaflets in the clinic. 32 patients in the clinic out of the 50 received a copy of the signed consent form.

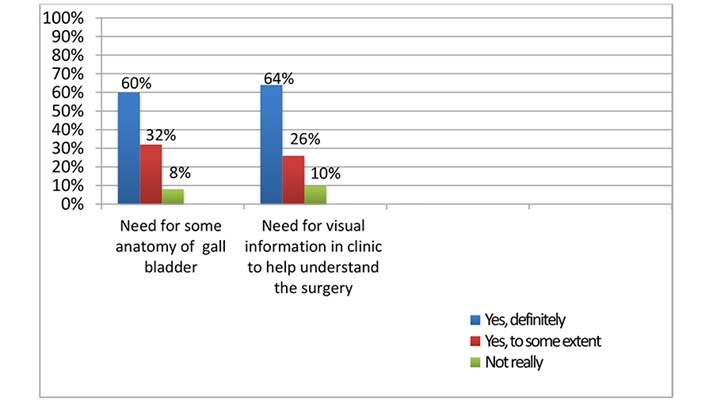

Thirteen patients did not remember the conversation in the clinic. Five patients were consented on the day of surgery. Most individuals agreed strongly that audiovisual aids would help in understanding the anatomy and the complex hepatobiliary risks from a laparoscopic cholecystectomy, see Graph 1.

Graph 1: survey of patients attending clinic for consideration of surgery.

We presented the survey results in our monthly audit meeting and started working on a short-informed consent video for clinics. The aim was to provide improved literature and a copy of the signed consent form to the patient.

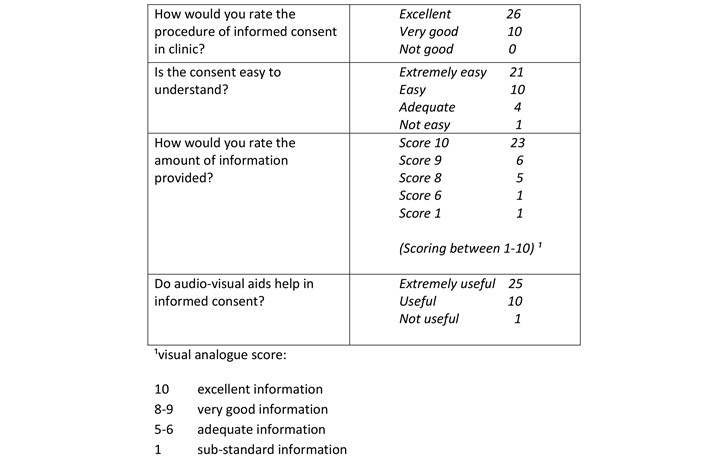

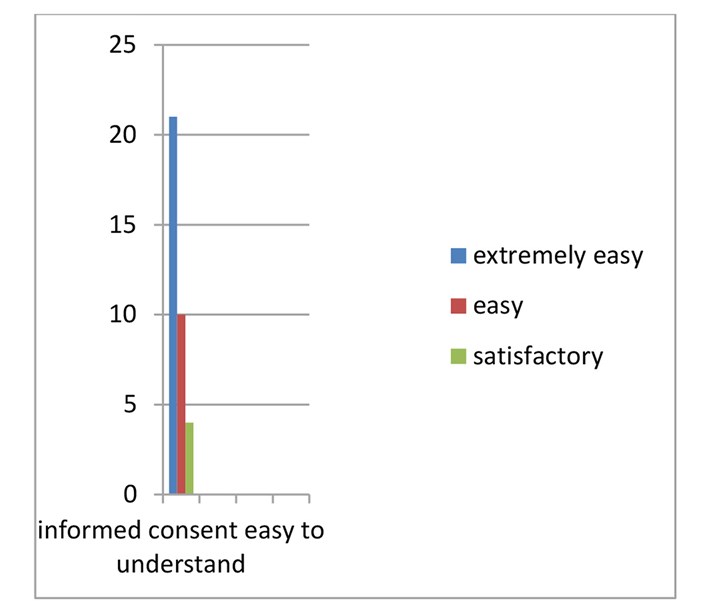

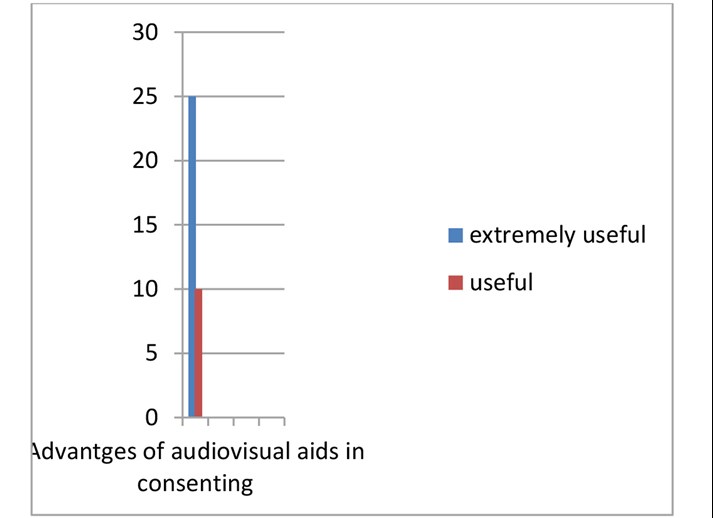

Work on the video involved making sure that not only all the relevant information is provided but is easily understandable. Animations rather than real time images by a trained audio-visual engineer provided comfortable viewing and avoided distressing patients. Our clinic consultation involved the standard informed consent procedure and display of the consent video. We provided the patients with a copy of the consent and literature to take home. We asked Individuals to fill the second survey after this process in clinic. We received excellent feedback from the 35 patients surveyed, see Table 1 and Graphs 2-4.

Table 1: Results of second questionnaire.

Graph 2: assessment of informed consent process.

Graph 3: Is the informed consent easy to understand?

Graph 4: Are audio-visual aids advantageous in consenting.

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy pathway.

Discussion

The current health system is undergoing gradual and constant reform. Though patient autonomy is paramount in the process of informed consent, this was not the case just 50 years ago. Until only 50 years ago, a paternalistic physician approach was preferred over the concerns of the patients. Even the Hippocratic writings of the fourth and fifth century BC provide an extremely disappointing history in the context of informed consent. The GMC guidance emphasises that you should, ‘share information in a way the patient can understand and, wherever possible, in a place and at a time when they are best able to understand and retain it’ (GMC 2008).

Due to the nature of service provisions in the National Health Service (NHS), the operating surgeon does not always encounter the same patient in clinic. Time constraints can sometimes even mean that individuals are consented on the day of the surgery. This is despite our hospital trust guidelines to consent individuals undergoing major procedures in clinics weeks prior to the surgery date. Unfortunately, it is practically impossible for specialists to see all the patients personally in certain high-volume cases like gallbladder and hernia surgery. The aim of our closed loop audit was to find the problems in our perioperative patient’s journey related to informed consent and to try to improve the information provided.

Elements of an informed consent form:

An effective and ethically valid informed consent needs to consider preconditions like competence on part of the patient to understand and make a decision and the voluntariness in deciding, free from controlling influence, including coercion, persuasion or manipulation.

The elements essential for information provided should include not only thorough disclosure of material information to the patient, including the alternatives, risks & benefits of treatment but also the physician’s recommendation of a plan.

The consent elements should include the decision in favour of a plan by the patient and authorization given by the patient of the chosen plan. (Beauchamp 2011)

Health education and its retention can improve with numerous techniques like literature about the procedure, ’repeat back’ to assess retention of knowledge, second clinic discussion and audio-visual aids.

Repeating the information provided in any form can be useful to make an informed decision. In a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT), individuals in the control group were consented the standard way and the experimental group assessed with ‘repeat back’ including standard informed consent. It was concluded after 575 patients assessed by a questionnaire that individuals benefitting from repeat back took longer to consent but had much improved comprehension of the procedure.(Fink et al. 2010)

Another smaller sized randomised control trial showed a simplified standard informed consent by highlighting text in bullet points and graphical illustrations improved health education in individuals undergoing surgery.

Thirty-seven individuals were consented in the standard way whereas 33 individuals had a graphically formatted, easy to understand consent form. Assessment questionnaires were filled in by the individuals showing improved comprehension of the surgical procedure and the risks.(Borello et al. 2016)

The use of multimedia including video and graphic illustrations aid in improving health education and the tools can repeated in the comfort of the individual’s own living room to reinforce the already acquired knowledge. We have prepared an animated video that provided information relating to the overall perioperative process in the setting of a typical district NHS hospital.

The video can be seen by clicking here.

The video can be seen by clicking here.

There are randomised control trials that used multimedia to improve the standard of the informed consent process. In a German RCT, 76 individuals were shown real-time as well as animated video of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. This video was prepared over a 3-year period with the collaboration of surgeons, psychologists and linguists that defined the major relevant topics. At the end of the consent with audio-visual aids and standard informed consent, thirty-five individuals were asked to fill in a questionnaire. Forty-one individuals were consented in the standard way. It concluded that audio-visual aids improved the perceived understanding of risks of surgery especially in those with less formal education. The drawback of the study was a small sample size. (Bollschweiler et al. 2009)

In a larger RCT from Germany, preoperative patient education using a multimedia digital versatile disc (DVD) improved the informed consent in patients undergoing a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. The University of Munich, Germany produced the DVD. One hundred and fourteen patients in the experiment group saw the DVD and underwent standard informed consent compared to 98 patients having a standard informed consent. It was 25 minutes long and involved a real time surgeon-patient interaction as well as animations. They came to the conclusion that individuals fluent in German language and were of a younger age benefitted the most due to better education and retention of health education. (Wilhelm et al. 2009)

There have been similar studies using multimedia facilities to improve the quality and amount of retention of health education for certain surgical procedures with very encouraging outcomes on standard questionnaires and scoring systems. However, in one study on individuals having cataract surgery, the retention of information decreased as age of the individuals increased. Age and mental ability needs to be taken into account while providing procedure information. (Tipotsch-Maca et al. 2016)

Contents of the informed consent need to include the most common and the most serious of complications, however consensus between even groups of surgeons can be difficult to attain because of a variety individual opinion and experience. There have been attempts to bridge this difficulty by applying techniques like the Modified Delphi Technique to achieve consensus and to optimise the information provided. A study used the above technique to deliver an informed consent video in individuals requiring debridement for limb trauma. A panel of experts including experienced patients decided on the final information to be included in the video. They used a ’final knowledge measure ‘questionnaire. The advantage was acquiring the consensus from all the experienced stakeholders including patients to build on the essential information provided to the patient. (Lin et al. 2017)

Despite our efforts to improve the process, we do acknowledge some weaknesses. Firstly, not all risks can be discussed in a short video and there are bound to be some risks (though uncommon) not included in the video. Secondly, some terms used in the video might be too technical for someone not from a healthcare background but had to be included to keep the video short.

The author believes that it takes about 3- 4 minutes to fill in the consent form and print out the literature while patients see the video. Once the video concludes and the consent form is ready, a thorough discussion takes place prior to formally signing the consent. The repetition assists in educating the individual thoroughly.

Conclusion

Informed consent is an opportunity to discuss the clinical management between the clinician and the individual undergoing an intervention rather than an exercise to fulfil legal requirements. To maintain this sacred bond between the patient and clinician, an informed consent that provides adequate knowledge and meaningful understanding should be of utmost priority. Multimedia can be utilised to improve this process.

References

- Sparkman RS. 1982. 100th Anniversary of the First Cholecystectomy: A Reprinting of the 50th Anniversary Article From the Archives of Surgery, July 1932. Arch Surg. doi:10.1001/archsurg.1982.01380360001001.

- Reynolds W. 2001. The First Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. J Soc Laparoendosc Surg.

- Clarke MG, Wheatley T, Hill M, Werrett G, Sanders G. 2011. An Effective Approach to Improving Day-Case Rates following Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. Minim Invasive Surg. doi:10.1155/2011/564587.

- Beauchamp TL. 2011. Informed consent: Its history, meaning, and present challenges. Cambridge Q Healthc Ethics. doi:10.1017/S0963180111000259.

- Fink AS, Prochazka A V., Henderson WG, Bartenfeld D, Nyirenda C, Webb A, Berger DH, Itani K, Whitehill T, Edwards J, et al. 2010. Enhancement of surgical informed consent by addition of repeat back: A multicenter, randomized controlled clinical trial. Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e3ec61.

- Borello A, Ferrarese A, Passera R, Surace A, Marola S, Buccelli C, Niola M, Di Lorenzo P, Amato M, Di Domenico L, et al. 2016. Use of a simplified consent form to facilitate patient understanding of informed consent for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Open Med. doi:10.1515/med-2016-0092.

- Bollschweiler E, Hölscher AH, Obliers R. 2009. Improving Informed Consent of Surgical Patients Using a Multimedia-Based Program? Ann Surg. doi:10.1097/sla.0b013e31819ac459.

- Wilhelm D, Gillen S, Wirnhier H, Kranzfelder M, Schneider A, Schmidt A, Friess H, Feussner H. 2009. Extended preoperative patient education using a multimedia DVD-impact on patients receiving a laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomised controlled trial. Langenbeck’s Arch Surg. doi:10.1007/s00423-008-0460-x.

- Tipotsch-Maca SM, Varsits RM, Ginzel C, Vecsei-Marlovits P V. 2016. Effect of a multimedia-assisted informed consent procedure on the information gain, satisfaction, and anxiety of cataract surgery patients. J Cataract Refract Surg. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2015.08.019.

- Lin YK, Chen CW, Lee WC, Lin TY, Kuo LC, Lin CJ, Shi L, Tien YC, Cheng YC. 2017. Development and pilot testing of an informed consent video for patients with limb trauma prior to debridement surgery using a modified Delphi technique. BMC Med Ethics. doi:10.1186/s12910-017-0228-3.

(Click on image to go to the company website.)

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34940/301-raza.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse6

Sanjeev Kotecha1 and Achal Khanna2

1 FY2, Oxford University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (formerly of Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust)

2 Consultant Upper GI Surgeon, Milton Keynes University Hospital NHS Foundation Trust

Contact: Sanjeev_Kotecha@hotmail.co.uk

Keywords: surgery, theatre, cancellations

Abstract

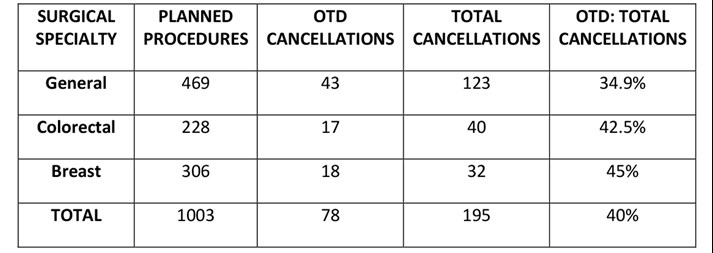

Introduction: The aim of this study is to evaluate on-the-day (OTD) theatre cancellations at Milton Keynes University Hospital (MKUH) and to identify the reasons behind these cancellations.

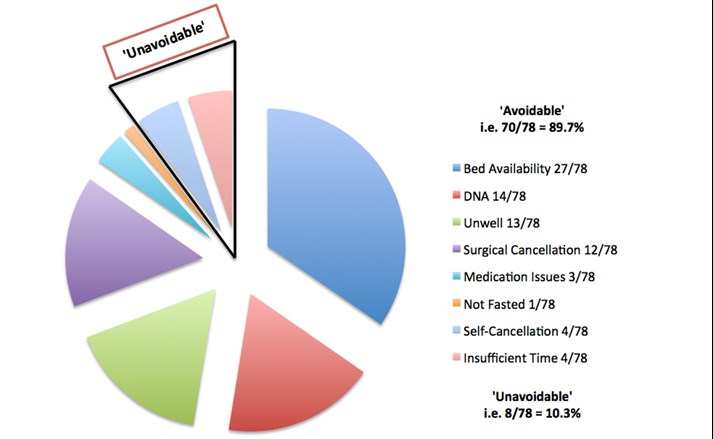

Methods: All patients undergoing elective surgery in the general, colorectal and breast surgery specialties over a six-month period were included. The reasons behind these cancellations were then ascertained using the electronic patient record system. Cancellations were defined as either ‘avoidable’: bed availability, did not attend (DNA), unwell, surgical cancellation, medication issues, not fasted; or ‘unavoidable’: insufficient time, self-cancellation.

Results: Out of 1003 planned procedures, 19.4% (195 patients) were cancelled overall. 40% of cancellations were identified as being OTD (78/195). Of these, 89.7% (70/78) were ‘avoidable’ with the most common reasons being bed availability (27/70) and DNAs (14/70). 10.3% (8/78) of OTD cancellations were deemed ‘unavoidable.’

Conclusions: OTD theatre cancellations account for significant financial burden across healthcare systems worldwide. Their unpredictable nature exacerbates wasted time of theatre staff and resources. The implementation of measures to reduce all kinds of OTD cancellations, especially ‘avoidable’ ones, would lead to increased efficiency and cost-effectiveness.

Introduction

Growing financial pressures on the National Health Service (NHS) and budget constraints mean that running a system that is efficient and economical as possible is essential. Operating theatres comprise a significant proportion of any hospital’s expenditure, which consists of utility bills, equipment, drugs and human resources [1], [2]. One area that has come under scrutiny is the cancellation of surgical procedures. It is well known that these cancellations can occur for a wide range of reasons, both clinical and non-clinical in nature. When procedures are cancelled in advance, it gives departments the opportunity to ensure that available slots are filled. However, cancellations that arise on-the-day (OTD) of any given procedure tend to lead to a waste of hospital resources. Given that these OTD cancellations are inherently difficult to predict, they are responsible for a substantial source of inefficiency in a system that is already fiscally burdened. This project aims to retrospectively assess OTD theatre cancellations at Milton Keynes University Hospital (MKUH) and to determine the reasons behind these cancellations.

Methods

For the purpose of this audit, patients that were booked to undergo elective surgical procedures by the general, colorectal and breast surgical specialties were included. This covers both day case surgery as well as patients requiring inpatient admission pre- and/or post-operatively. Emergency cases were not considered. A six-month period of January – June 2018 was used for patient selection in this study in order to account for any seasonal disparities that may exist in OTD cancellations [3]. Once eligible patients had been identified, the local electronic patient record system was used for data acquisition so that the circumstances leading to the cancellations could be determined.

Cancellations were categorised as being ‘avoidable’ or ‘unavoidable.’ ‘Avoidable’ cancellations include bed availability (i.e. insufficient capacity), did not attend (DNA; implies that the hospital is not notified of non-attendance), unwell (e.g. respiratory tract infection), surgical cancellation (deemed no longer necessary on the day by the lead surgeon or the procedure is cancelled for anaesthetic reasons e.g. further pre-operative assessment is required), medication issues (e.g. oral anticoagulants not being stopped in a timely manner), not fasted (e.g. patient has eaten just prior to their procedure). ‘Unavoidable’ cancellations include: insufficient time (e.g. other cases over-running), self-cancellation (whereby the patient cancels their own procedure but does not inform the hospital until the day of the procedure).

Results

There was a total of 1003 planned elective procedures to be carried out by the above specialties in the six-month period. 19.4% (195/1003) of overall procedures were cancelled, with 40% of these (78/195) being OTD cancellations (Table 1). The nature of the OTD cancellations was assessed to determine whether they were ‘avoidable’ or ‘unavoidable’ (Figure 1). 89.7% (70/78) of OTD cancellations were deemed to be ‘avoidable.’ A lack of available beds was the most prevalent reason, accounting for over a third of all OTD cancellations (27/78). DNAs, the patient being too unwell for surgery as well as a decision by the surgical/anaesthetic team to cancel the procedure were all approximately equal in their incidence, each accounting for 15-20% of OTD cancellations (n. = 14, 13 and 12 out of 78 respectively). 10.3% (8/78) of OTD cancellations were ‘unavoidable,’ with insufficient theatre time and self-cancellations each being responsible for 4 out of the total 8 ‘unavoidable’ OTD cancellations.

Table 1 – Total number of planned procedures per specialty with a breakdown of cancellations (both OTD and total).

Figure 1 – Pie chart depicting breakdown of ‘avoidable’ and ‘unavoidable’ OTD cancellations.

Discussion

Over the time period surveyed, OTD cancellations represented 40% of the total cancellations of planned procedures at MKUH. In comparison, a 2018 prospective, cohort study examined theatre cancellations over a one-week period across almost 250 NHS hospitals. Approximately 15,000 patients were included and OTD cancellation rate was found to be 13.9%, much lower than in this study at MKUH [4]. When compared with the official NHS England statistics, the overall cancellation rate nationally was 1% for the same six-month period of 2018, compared to 19.4% overall cancellation rate found in this study at MKUH [5]. Data on cancellations that are specifically OTD, is no longer collected on a national scale; instead data on ‘last minute’ cancellations is routinely collated, and this involves a larger subset of patients compared to OTD cancellations. When put into perspective, it is evident that the cancellation rate at MKUH is far less favourable compared to other studies and nationally.

When assessing the reasons behind OTD cancellations, it was found that 89.7% were ‘avoidable,’ with 10.3% ‘unavoidable.’ However, these definitions are certainly equivocal and debatable. Some of the ‘avoidable’ reasons in this study can be regarded as being difficult to prevent. For example, a lack of bed availability could be secondary to a variety of unforeseen factors but addressing this by revising bed space forecasting could make a substantial difference in reducing OTD cancellation rates. DNAs could be improved by better communication between the hospital and the patient (e.g. sending electronic or telephone reminders), and surgical cancellations (by either the surgical or anaesthetic teams) could be improved by establishing local pathways [6]. These three ‘avoidable’ reasons accounted for the majority of all OTD cancellations. Being unwell OTD of surgery cannot be predicted but unless the patient has become unwell within 24 hours of admission, this is another potentially preventable cause for cancellations, again through improved communication between the hospital and the patient. Medication and fasting issues can be targeted through relatively simple measures such as electronic protocols. In terms of the ‘unavoidable’ cancellations, insufficient theatre time often arises due to preceding cases overrunning. Nonetheless, there are times when teams feel as though theatre lists have been over-booked, which is something that can certainly be prevented. Finally, patients calling OTD of surgery to cancel their procedure (self-cancellation) is obviously difficult for hospitals to predict in advance but this could be mitigated in many cases by improved peri-operative communication with patients. Despite being classified as ‘avoidable’ and ‘unavoidable,’ it can be argued that these are all areas worth targeting due to the wide-ranging consequences of OTD cancellations, including: economic, clinical and service-related implications [7].

Given the current economic situation of the NHS, ensuring that all areas of healthcare provision are as cost-effective as possible is essential. A recent study in Finland evaluating the cost of OTD cancellations showed that the average wasted expense for one procedure is around €2,500 [1]. Similar studies in the USA show mean costs that are approximately double this figure [8]. The financial losses incurred are due to a variety of reasons, ranging from wasted time of theatre staff to wasted medications, as well as other wasted resources such as materials and utilities. Additionally, these squandered resources lead to unnecessary harm to the environment. Clinical and patient-related implications are also important to consider. Although these procedures are carried out on an elective basis and may not necessarily be life or limb-saving procedures, patients are forced to endure their symptoms for longer if procedures are cancelled. From a psychological wellbeing point of view, patients have to suffer the stress and disappointment of hearing that their procedure has been cancelled at such short notice [9]. Moreover, there is evidence to suggest surgical outcomes are poorer as a result of OTD cancellations [10]. Service-related implications are another key factor to examine. Not only are these cancellations leading to waiting lists becoming increasingly protracted, but they are also hindering the clinical flow of patients, especially inpatients who have been admitted specifically for their procedure [11].

As far as limitations of this study are concerned, it is important to point out that not all surgical specialties have been considered. Furthermore, despite the sample period being a six-month window (to try and mitigate any disparities that might exist between summer and winter months [3]), the sampling period coupled with a sample size of 1003 patients are relatively small. Ideally the acquisition of data that is similar to that of this study needs to be carried out on a larger scale to truly establish any generalisable trends.

To conclude, the reasons behind OTD cancellations can be complex and multi-factorial. Nevertheless, given the significant consequences that they can have from an economic, clinical and service standpoint, it is crucial to try and improve the rates of theatre cancellations. The often-unpredictable nature of OTD cancellations makes the task more difficult but targeting both ‘avoidable’ and ‘unavoidable’ reasons should be a priority at the forefront of all surgical departments nationally. Plans are in place to try and improve peri-operative communication with patients, through either electronic or telephone reminders, in an attempt to address several causes for OTD cancellations. It would then be prudent to re-evaluate for any discernible and viable improvement, in order to try and create a safer, more efficient and cost-effective service.

Acknowledgements

Dominic Larner (Theatre Information Administrator, MKUH).

References

- Turunen E., Miettinen M., Setälä L. et al.; Financial cost of elective day of surgery cancellations; Hosp. Adm.; 2018; 7(6); pp.30-6.

- Macario A.; What does one minute of operating room time cost? Clin. Anes.; 2010; 22(4); pp.233-36.

- Royal College of Surgeons England; Over 62,000 fewer operations performed this winter, following necessary cancellations; RCS Eng.; 2018.

- Wong DJN, Harris SK and Moonesinghe SR; Cancelled operations: a 7-day cohort study of planned adult inpatient surgery in 245 UK National Health Service hospitals; BJA; 2018.

- Performance Analysis Team; Cancelled Elective Operations; NHS England and NHS Improvement; 2019.

- Olson R.P. and Dhakal I.B.; Day of surgery cancellation rate after preoperative telephone nurse screening or comprehensive optimization visit; Med. (Lond.); 2015; 4(12).

- Caesar U. Karlsson J., Olsson L.E. et al.; Incidences and root causes of cancellations for elective orthopaedics procedures: a single center experience of 17,625 consecutive cases; Patient Saf. Surg.; 2014; 8(24).

- Pohlman G.D., Staulcup S.J., Masterson R.M. et al.; Contributing factors for cancellations of outpatient pediatric urology procedures: single center experience; Urol.; 2012; 188(4); pp.1634-8.

- Leslie R.J., Beiko D., van Vlymen J. et al.; Day of surgery cancellation rates in urology: identification of modifiable factors; Urol. Assoc. J.; 2013; 7(5-6); pp.167-73.

- Magnusson H., Felländer-Tsai L., Hansson M.G. et al.; Cancellations of elective surgery may cause an inferior postoperative course: the ‘invisible hand’ of health-care prioritization? Ethics; 6; pp.27-31.

- Lau H.K., Chen T.H., Liou C.M. et al.; Retrospective analysis of surgery postponed or cancelled in the operating room; Clin. Anesth.; 2010; 22(4); pp. 237-40.

(Click on image to go to the company website.)

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34939/301-kotecha.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse7

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34947/breast-day-surgery-feb-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse8

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34952/bads-day-case-major-knee-surgery-april-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse9

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34953/bads-day-case-hip-may-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse10

Andrei Tanase

Andrei is a ST7 General Surgery trainee with a special interest in Hepatopancreatobiliary (HPB) Surgery. Andrei has been the Association of Surgeons in Training (ASiT) Severn Representative for the last 2 years and recently he has been involved with the British Association of Day Surgery (BADS). Andrei hopes his interest for improving day case surgery and his IT and technology skills will prove a great asset to BADS and contribute to improving and developing day surgery.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34950/301-new-council-members.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse11

Professor P E M Jarrett (1943-2019) MA MB BChir FRCS

We have lost a champion of Day Surgery. Personally, I have lost a dear friend and colleague. Paul graduated from Cambridge University (1966) and after medical and surgical appointments at St Thomas’s Hospital, London he became Consultant in General and Vascular Surgery at Kingston Hospital (1977-2003). He was appointed Professor of Day Surgery and Acute Day Care at Kingston University and St. George’s Hospital Medical School (1996-2017).

Paul Jarrett had a global following especially in the field of day surgery. His earlier work on day surgery for inguinal repair proved a classic. In 1989 he became a Founding Member of the British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) and was elected its first Chairman and a member of the editorial board of the Journal of One-Day Surgery. In 1995 he was a Founding Member of the International Association of Ambulatory Surgery, an organisation to which 30 countries were affiliated. Paul became the President of the IAAS (1997-99). In 1997 he became an Honorary Life Member of BADS and in 2013 he was elected an Honorary Member of IAAS.

Paul and I teamed up following a series of meetings on day surgery when we addressed such subjects as how to establish day units, how they should be administered and pointed to the need for education and research in the field. The surgical waiting list in England & Wales stood at over one million patients so could a planned programme of day surgery alter this situation. Together we agreed that a national Association of Day Surgery might be the answer, but we were aware of strong opposition to our plans. To make them work we decided to establish a Multidisciplinary Association and the first BADS Congress was held at the Royal Society of Medicine in London. The main lecture theatre was booked for 200 delegates but on the day a further 50 people attended. Immediately Paul and I decided that there was great interest in day surgery and that we should increase our efforts to impress the NHS, the Secretary of State for Health, the Department of Health and Sponsors for finances to spread the good word. As we all know BADS is now safely established at the Royal College of Surgeons England and BADS celebrated its 30-year Anniversary this year.

In the earlier years the BADS committee met regularly in London pubs, hotels and at Barnet Hospital, Postgraduate Centre. Meetings were never cancelled and despite the heavy workload involved our committee would probably all do the same again. It was fun, especially when hundreds of day units were established throughout the United Kingdom.

Throughout this hectic period Paul was a busy general surgeon on regular emergency duties. However, he became Editor of the Journal of Ambulatory Surgery and wrote over 80 publications. In addition, he delivered 25 UK Guest Lectures and 45 Overseas Guest Lectures. Over the years he assisted in the organisation of 18 UK Congresses and 13 International Conferences. What energy! His new Kingston Hospital Day Unit welcomed visitors from 23 different countries and of course they always invited Paul to spread the gospel at their own national meetings.

Paul also had a life outside of medicine, he served on the Boards of several public and private companies both national and international. He was a founder trustee of a local hospice. Few people will be aware that he was elected as a Freeman of the Company of Arts Scholars, Dealers and Collectors. In addition, he held the office of Master of the Worshipful Company of Clockmakers (London).

Paul Jarrett was my friend. He was an enthusiast with abundant energy, a natural leader, an outstanding lecturer, a talented organiser. He was a very sociable person and lived life to the full. Our condolences go to Annie his dear wife and to his son Michael, a Consultant Surgeon at Kingston upon Thames.

Dr Tom W Ogg

Formerly Consultant Anaesthetist

Director Day Surgery

Addenbrookes Hospital

Cambridge

Past President, British Association of Day Surgery (BADS)

Past President, International Association of Ambulatory Surgery (IAAS)

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34951/301-jarrett.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse12

General Guidelines

The Journal of One-day Surgery considers all articles of relevance to day and short stay surgery. Articles may be in the form of original research, review papers, audits, service improvement reports, case reports, case series, practice development and letters to the editor. Research projects must clearly state that ethics committee approval was sought where appropriate and that patients gave their consent to be included. Patients must not be identifiable unless their written consent has been obtained. If your work was conducted in the UK and you are unsure as to whether it is considered as research requiring approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), please consult the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool at http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Articles should be prepared as Microsoft Word documents with standard line spacing and normal margins. Submissions must be sent by email to the address below.

Copyright transfer agreement and submission

As of 7th November 2019, the JODS copyright transfer agreement must be downloaded from the resources section (tab) via the BADS website:

https://daysurgeryuk.net/en/resources/documentation/

Each named author should complete and sign a copy. Scanned copies/legible photos should be sent via email together with the main manuscript to the JODS editor: davidbunting@nhs.net

Any source of funding should be declared and authors should also disclose any possible conflict of interest that might be relevant to their article.

Submissions are subject to peer review. Proofs will not normally be sent to authors and reprints are not available.

Manuscript preparation

Title Page

The first page should list all authors (including their first names), their job titles, the hospital(s) or unit(s) from where the work originates and should give a current contact address for the corresponding author.

The author should provide three or four keywords describing their article, which should be as informative as possible.

Abstract

An abstract of 250 words maximum summarising the manuscript should be provided and structured as follows: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions.

Main article structure

Manuscripts should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and References. Tables and figures should follow, with each on a separate page. Each table and figure should be accompanied by a legend that should be sufficiently informative as to allow it to be interpreted without reference to the main text.

All figures and graphs are reformatted to the standard style of the journal. If a manuscript includes such submission, particularly if exported from a spreadsheet (for example Microsoft Excel), a copy of the original data (or numbers) would assist the editorial process.

Copies of original photographs, as a JPEG or TIFF file, should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedding pictures within the text of the manuscript.

Tables, Figures and Graphs

Please submit any figures, graphs and images as separately attached files rather than embedding non-word files into the word manuscript document. Tables constructed in MS Word can be left in their original MS Word file including the manuscript if this is where they were drawn.

Figures and graphs can be presented in colour but try to avoid 3-d effects, shading etc. Figures and graphs may be redrawn if the quality is not in keeping with the Journal. Please make it clear within the manuscript text where you would like tables, graphs or images to be placed in the finished article with the use of a brief explanatory legend in the manuscript file where you wish the item to be placed, e.g.

Table 1. Patient demographic details.

Figure 1. Proportion of procedures performed as a day-case each year between 2005 and 2018.

Photographs

Photographs can be provided as jpg or tiff files but should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedded within the text of the manuscript. This ensures higher quality images. However, we will accept images within Word documents but image quality might suffer!

References

Please follow the Vancouver referencing style:

- References in the reference list should be cited numerically in the order in which they appear in the text using Arabic numerals, e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4 etc.

- The reference list should appear at the end of the paper. Begin your reference list on a new page and title it 'References.'

- Cite articles in the manuscript text using numbers in parentheses and the end of phrases or sentences, e.g. (1,2)

- Abbreviate journal titles in the style used in the NLM Catalogue: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog?Db=journals&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=currentlyindexed%5BAll%5D

- The reference list should include all and only those references you have cited in the text. (However, do not include unpublished items such as correspondence).

- Check the reference details against the actual source - you are indicating that you have read a source when you cite it.

- Be consistent with your referencing style across the document.

Example of reference list:

- Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281.

- Dybvig DD, Dybvig M. Det tenkende mennesket. Filosofi- og vitenskapshistorie med vitenskapsteori. 2nd ed. Trondheim: Tapir akademisk forlag; 2003.

- Beizer JL, Timiras ML. Pharmacology and drug management in the elderly. In: Timiras PS, editor. Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. p. 279-84.

- Kwan I, Mapstone J. Visibility aids for pedestrians and cyclists: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(3):305-12.

- Barton CA, McKenzie DP, Walters EH, et al. Interactions between psychosocial problems and management of asthma: who is at risk of dying? J Asthma [serial on the Internet]. 2005 [cited 2005 Jun 30];42(4):249-56. Available from: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/.

Mr David Bunting

Editor, Journal of One Day Surgery

Consultant Upper GI Surgeon

North Devon District Hospital

[These guidelines were last revised on 02.11.2019]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34946/author-guidelines.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1902#collapse13