Dave Bunting

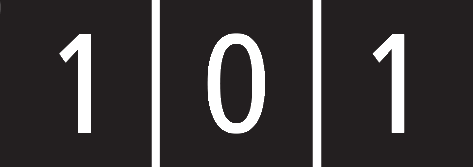

It is very disappointing that due to COVID-19 restrictions, the Annual Conference cannot be held as planned at the Cardiff City Hall on 25th and 26th June. However, you will probably be aware that instead, it will now be taking place on 18th-19th March 2021 at the same venue. The good news is that gives you more time to prepare your abstracts for submission with a new deadline of Friday 8th January 2021. Any abstracts already submitted for the original date are valid for the new date. This may seem a long time away but what better opportunity to catch up with audit /research work whilst elective NHS activity is reduced and submit your abstracts. With that in mind, I encourage you to put the new dates into your academic diaries and book study leave with your trust in advance if possible. This is the link to abstract submission:

https://app.oxfordabstracts.com/login?redirect=/stages/1625/submissions/new

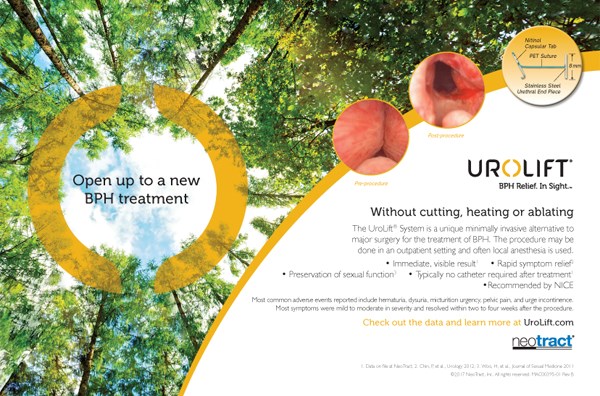

This year BADS again plans to co-host several national and regional meetings in association with external organisations such as Health Care Conferences UK (HCUK) pending the lifting of social distancing restrictions. These are the conferences currently planned for later in the year:

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Developing your Daycase General Surgery Service will be held on Thursday 17th September at the De Vere West One Conference Centre, London

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Day Case Total Hip Replacement will be held on Wednesday 4th November 2020 at the Studio Conference Centre, Birmingham

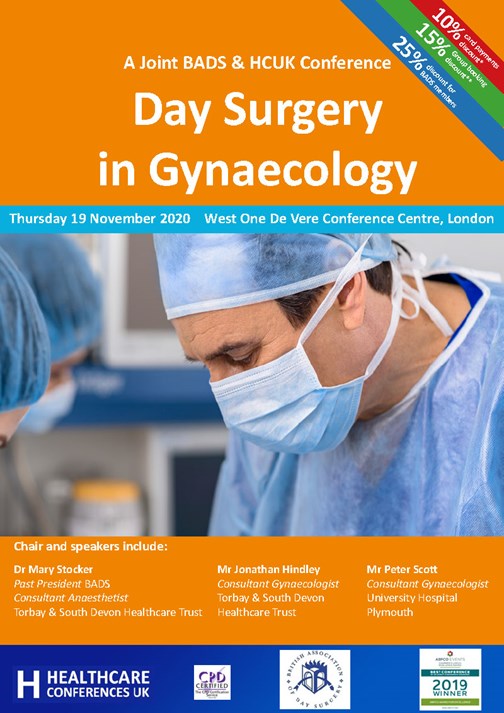

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Day Surgery in Gynaecology will be held on Thursday 19th November at the De Vere W1 Conference Centre, London

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Breast Surgery as Day Surgery will be held on Tuesday 1st December at the Studio Conference Centre, Manchester

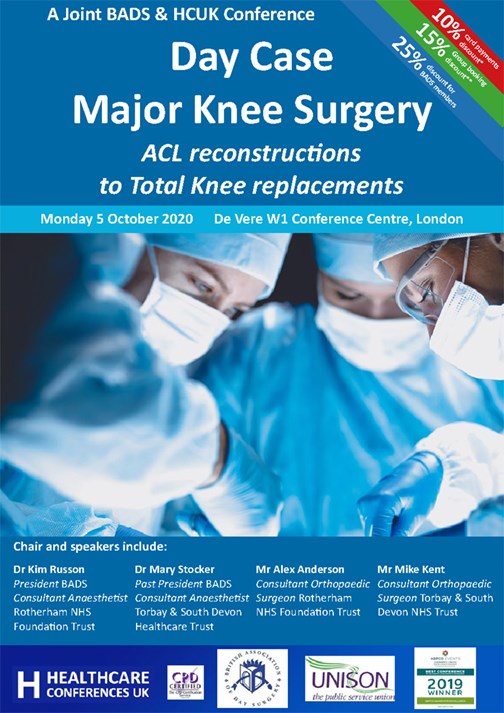

- BADS/HCUK Conference on Day Case Major Knee Surgery will be held on Monday 5th October at the De Vere W1 Conference Centre, London

Further details of all the above conferences can be found in this edition of JODS.

Original papers in this edition of JODS include a summary of the recently published Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) Society guidelines on Perioperative Care in Hip and Knee Arthroplasty; a report on the benefits of a dedicated Day Surgery Unit from Torbay, Devon and an evaluation of ambulatory emergency pathways looking at whether the 75% overall daycase target could be extended to emergency surgery.

Please keep your submissions to the Journal coming in and remember – JODS still offers citable peer-reviewed publication with no author processing fees.

With the Covid-19 prevalence falling, day surgery units offer great opportunity to facilitate restarting elective operating. They use established (and often telephone-based) pre-operative assessment pathways. They are often based in stand-alone units, physically distanced from other hospital departments, with their own entrances and exits and a natural separation from emergency departments and inpatient wards. Therefore, they are often ideally equipped to manage Covid-negative patients in so called ‘Green’ zones.

Most importantly, in these difficult times – stay safe, look after yourselves and your patients.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37943/302-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse0

Kim Russon

I hope you are well and coping with the challenges resulting from COVID-19. I am acutely aware that we are living in exceptional times and this pandemic has and will continue to place levels of demand on our NHS that none of us have previously experienced. I am also conscious that many of us are designated as key workers. Some of us are also carers. It is important to consider your own wellbeing and there a number of resources that have been made available to NHS staff and so BADS has provided links to some of these on our website.

Although nationally day surgery has had to take a back seat during the pandemic, there are a number of processes that as a society BADS has had to continue with and BADS council have responsibilities which we must address. A number of BADS conferences have understandably been postponed and you should have recently received an update of the proposed new dates via email. We are mindful that we are still living in uncertain times and these dates may need to be reviewed. With the postponement of our annual conference to March 2021 we have had to consider our AGM which we have decided to hold as a virtual meeting on Thursday 25th June time at 12midday.

We have managed to hold our council elections and I am delighted to welcome 4 new members of council, Dr Matthew Checketts, Miss Vanessa Cubas, Mrs Catherine Jack and Dr Rachel Morris. All have been involved in day surgery for a number of years and I am confident will be active in supporting and progressing the work of BADS. More information on our new council members will be published in the next edition of JODS. I am sad to announce that Dr Madhu Ahuja stepped down from BADS council in February. Madhu has been on council for almost 9 years and edited numerous BADS booklets and managed the BADS website for many years. She has been International Association of Ambulatory Surgery (IAAS) representative for the last 3 years. Her knowledge, experience and hard work will be missed and I thank Madhu for all of the time end effort she has given to BADS.

With the announcement by Health Secretary Matt Hancock on 27th April 2020 that elective surgery can restart according to local circumstances then hopefully we will see increase in day surgery activity again. The website formed by collaboration between intensive care and anaesthesia https://icmanaesthesiacovid-19.org has many useful resources relating to the COVID-19 pandemic including a document on Restarting planned surgery in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. This document published on 1st May 2020

“seeks to ensure that planned activity matches a realistic assessment of the ability of NHS staff and resources to deliver this activity. It is essential that when the resumption of planned surgery takes place, care is delivered safely, efficiently and in a sustainable manner, taking into account the staffing, environment and equipment needed to operate, but also the continuing impact of care of COVID-19 patients on postoperative critical care capacity.”

As planned surgery is reintroduced I believe it is important to plan as much surgery as possible a day surgery. It is reasonable to consider any procedure in the BADS Directory of Procedures 6th Edition as a suitable day case and then to ask the question “what would be done differently if they were to be kept in overnight? “ Guidance on how to develop day case general surgery, knee surgery, hip surgery, gynaecological surgery and breast surgery can be obtained by attending the BADS/HCUK conferences planned for later this year. The BADS booklets also provide a wealth of information and are available from the BADS website including two recently published booklets: Day case Breast Surgery and Surgical Same Day Emergency Care.

Please let's all look out for one another, stay safe and well.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37948/302-president.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse1

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37936/2021-prog-3.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse2

Download the 2021 Conference pdf by clicking

the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37946/2021-prog-1.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse3

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse4

Dr Ciska Uys (Core Trainee in Anaesthesia), Dr Theresa Hinde (Consultant Anaesthetist), Mr Kirk Bowling (Consultant Upper GI Surgeon), Dr William Hare (Specialist Registrar in Anaesthesia), Dr Mary Stocker (Consultant Anaesthetist)

Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Torbay, United Kingdom

Keywords: emergency surgery, ambulatory surgery, quality improvement, day surgery

Abstract

Introduction: Elective day surgery rates have increased dramatically over recent years with more patients with complex medical and social needs being considered appropriate for day surgery and many more challenging procedures entering the day surgery arena. Whilst some minor emergency procedures such as abscess drainage and surgical management of miscarriage have been managed via day case pathways in some trusts for a number of years. Many trusts still have no established day case pathway for these procedures and day case rates are by no means universally high across the country. In addition, management of more complex emergency procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy, appendicectomy and ureteric stone surgery routinely as day surgery is not routine in most UK trusts. We describe the introduction of new ambulatory pathways for more complex surgical procedures which have been developed following the success of our minor day case emergency pathways.

Methods: Four ambulatory pathways successfully function at our hospital. Well-established discharge processes give surgical teams confidence to broaden the scope of surgery undertaken as day case. A novel planned ambulatory emergency pathway allows any appropriate acute surgical patient to be discharged home and return to the Day Surgery Unit (DSU) when there is a dedicated day case emergency list. It encourages emergency patients to be transferred from inpatient wards to DSU for surgery and subsequent same day discharge. This has enabled more complex emergency surgical procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendicectomy to be introduced to the day surgery arena. 12 years outcome data in terms of day case rates, rates of unplanned admissions and post-operative symptoms and satisfaction were obtained from our electronic patient record system. These were analysed retrospectively.

Results: Established emergency ambulatory pathways: In 12 years, 1831 patients underwent drainage of abscess and 1017 (56%) had a length of stay of 0 days (LOS=0), while 1540 women required Surgical Management of Miscarriage (SMOM) and 1102 (72%) had LOS=0.

New Ambulatory Pathways: Over 22 months (April 2017 to January 2019), 442 patients (18 children, 424 adults) underwent emergency surgery via a novel ambulatory pathway. This freed 385 hours 52 minutes of emergency theatre time and saved 671 bed days with estimated cost of £268,400. In addition, inpatients were identified as appropriate for day case and streamlined to DSU following surgery, with 75% successfully discharged. Since the pathway’s introduction, emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy day case rates have increased from 0 to 30%.

Conclusion: Robust ambulatory emergency pathways for appropriately selected cases can improve patient flow and experience while saving emergency theatre time and reducing bed occupancy. Ambulatory emergency surgery should be considered at any stage of a patient’s journey. Pathways can serve different patient groups with a common goal. Ideally admission is avoided altogether, but appropriately selected inpatients are streamlined to save post-operative stays.

Introduction

Increasing demand continues to put enormous pressure on NHS trusts. In the UK, the number of hospital admissions increased by 0.5% in the last year and is 23.5% higher than 10 years ago (1). A significant proportion of acute surgical patients occupy hospital beds while awaiting minor or intermediate emergency procedures, which are often delayed by major procedures rightfully taking priority. The result is increased bed occupancy, unnecessary prolonged fasting and patient dissatisfaction. Combined with unforeseen cancellations or under-booked elective lists, this caused frustration among our workforce who felt they could be delivering better care.

Elective ambulatory surgery continues to evolve and be offered for increasingly complex procedures. Over the last decade it has become clear that the same processes can serve to deliver safe ambulatory emergency surgery. The IAAS defines ambulatory emergency surgery as the management of an emergency patient according to an ambulatory surgical pathway, avoiding overnight stay following their surgical procedure. The authors also aim to avoid pre-operative stays. Patients requiring surgical management of miscarriage or incision and drainage of an abscess are often well enough to be discharged home with a safety net, while awaiting definitive management. Many trusts will already have functioning pathways for these procedures which may be a foundation for developing an extended emergency ambulatory service. However benchmarked data from NHS England (Model Hospital), shows that a large number of trusts do not achieve high day case rates for even these routine emergency procedures let alone more complex surgery. At Torbay Hospital an abscess pathway has been used for 15 years and has transformed the care of these patients, with mean length of stay reduced by 28 h 20mins (2). Moreover, it optimised the use of NCEPOD theatre time, by increasing operating during the first hour in the morning. The authors describe the transformation of emergency surgical services by learning from these established pathways and using expertise to develop day case pathways for more complex emergency surgery

In 2013, the Royal United Hospital in Bath piloted an Emergency Surgery Ambulatory clinic and found that 71% of acute patients seen by a consultant surgeon could be diagnosed and discharged on the same day with a planned operating date. By 2016, 82% of these patients were discharged on the same day and 85-90 bed stays were saved every month. Freed up theatre capacity meant that pre-operative stays reduced, and laparotomies went to theatre sooner (3). BADS 2019 guidelines (4) issued a table of emergency procedures suitable for day surgery (Table 1) which includes laparoscopic cholecystectomy and appendicectomy. Initiatives such as Chole-QuIC have been successful in reducing the time to surgery for patients requiring emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomy (5). However very few hospitals are managing these cases on a day case basis. (NHS England Model Hospital Data). In 2017, key opinion leaders of day surgery at Torbay hospital were inspired to expand its ambulatory emergency service in a cost neutral fashion. This report aims to describe the pathways in use at Torbay hospital with supporting outcome data. The purpose of the work is to emphasise the possibility of making day surgery the routine standard of care for the majority of emergency surgery.

Methods

Ambulatory Emergency Pathways

Torbay Hospital is a district general hospital in Devon with a successful standalone Day Surgery Unit (DSU). The DSU performs above the national standard in terms of day case rates for many elective procedures and has pioneered a number of challenging procedures on a day case basis. Its success is driven by a highly trained and motivated multidisciplinary team who follow robust admission and discharge processes. This includes electronically generated take home prescriptions and standardised routine telephone follow up to all patients on the day after their discharge, which enables robust audit of patient outcomes.

Emergency ambulatory surgery occurs via a number of different pathways. Here, we describe four functioning pathways at Torbay Hospital, starting with the earliest. We retrospectively reviewed patient records and identified patients with a length of stay of 0 days (LOS = 0) as well as those discharged on the same day as their surgery (who may have had a LOS>0 due to preoperative admission). Data was obtained from the hospital electronic patient record (Galaxy Surgery © CSC) which provides detail of every patient undergoing surgery in the trust. For patients who are managed via a day case pathway, it includes whether they were admitted or discharged, reason for unplanned admission and outcome data obtained from a routine telephone call the day after surgery. All data is entered contemporaneously by the clinical staff and is used to drive continuous service improvement and evaluation of the services provided.

Abscess pathway

This pathway has been used since 2005. Patients presenting to the emergency department (ED) or ambulatory medical unit (AMU) via their GP are evaluated by the on call surgical team. If they require incision and drainage and the patient is medically and socially suitable for ambulatory surgery, they can be discharged home with advice to return to DSU the following morning. From there, they are readied for theatre by day surgery staff and either sent for by the main emergency theatre or operated on in a dedicated day surgery emergency list. These cases often serve as the ‘golden patient’ and maximise use of the first hour of operating in the morning. If operated on in the main theatre complex, they return to the DSU after primary recovery for discharge via the day case pathway.

A retrospective search of the hospital theatre IT system found all cases of ‘incision and drainage of skin abscess’ since March 2008. Length of stay, type of anaesthetic and telephone follow up data were reviewed.

Surgical management of miscarriage (SMOM) Pathway

Women who present to the Early Pregnancy Unit (EPU) with confirmed miscarriage are given a choice of medical or surgical management. When opting for surgical management, these patients can go home with analgesia and instructions to return to the DSU on a day where there is an elective day case gynaecology list. We have agreement that one of these procedures can be added to any of the 4 elective lists undertaken in DSU per week. When it is not possible to give them a date within 10 days (which is unusual), they are instructed to return to AMU on a day when a surgeon is available. They may then be operated upon on one of our dedicated day surgery emergency lists or await available time on the NCEPOD theatre list. Following uncomplicated surgery, patients are taken to DSU for secondary recovery and discharge. A dedicated DSU emergency list is preferable as there may be delays waiting for main theatre making same day discharge less likely. A proportion of patients are offered manual vacuum aspiration (MVA) in an outpatient clinic if a skilled operator is available.

Suffering the loss of a pregnancy is upsetting and beyond a woman’s control. Supporting these vulnerable patients to remain the privacy of their own home with their own families until the day of surgery may restore a sense of control in their care.

We retrospectively reviewed all cases undergoing evacuation of contents of uterus that were typed as ‘urgent’ or ‘emergency’ since March 2008.

Planned ambulatory emergency

This pathway involves any acute surgical presentation and challenges clinicians to consider ambulatory emergency surgery as the norm and not the exception. During a half term in 2017 it was first noted that there were occasionally vacant but fully staffed theatre lists within our day Surgery Unit. It may not be uncommon in other hospital trusts, that during holiday periods there is nursing complement, but no scheduled elective activity due to maximum numbers of medical staff taking annual leave. Once identified by senior nurses at scheduling meetings, these lists are timetabled as ‘day case emergency’ lists and highlighted to surgical teams in advance. Surgical teams identify patients from the acute take that are suitable for day case surgery and have the opportunity to discharge them with instructions to return to the DSU on a day where there is a dedicated day case emergency list. The teams are comfortable with the process having used the aforementioned abscess and SMOM pathways for many years with a well-established discharge pathway.

There is now growing confidence to ‘push’ the boundaries of the types of surgical cases successfully performed as ambulatory emergencies. Our approach to achieving this is based on our guidelines for routine surgery. All patients are considered appropriate for day surgery as long as appropriate social support is available and any medical co-morbidities are stable. Patients are excluded if they have on-going sepsis likely to require post-operative support or intravenous antibiotics. The day surgery emergency lists allow a mix of surgical specialities and maintains safety by briefing again if the team changes. There may be an allocated anaesthetist or it may be covered by the on-call team. Care is taken to order the ambulatory emergency list to optimise the chance of successful same day discharge and avoid overrunning into scheduled elective lists. This involves doing more complex operations in the morning or first in the afternoon. In addition to planned patients scheduled onto these lists, if space allows, any other appropriate emergency patients are considered for this pathway. This currently relies on a number of individuals and particularly the anaesthetic emergency team to co-ordinate. There is a tick box on the emergency theatre booking form to prompt surgeons to consider using the day case pathway and ensure that it is considered for all emergency patients booked for theatre. A nursing representative from DSU attends morning handover and asks anaesthetic and surgical teams to identify any patients who are day case suitable.

This cost-neutral pathway reduces bed days, frees emergency theatre time, and increases satisfaction for patients and staff. It also means nursing capability is fully utilised in theatre rather than being drafted to other areas of the hospital, which impacts job satisfaction. Due to its success, surgeons expect to see regular lists and we have now amended our theatre timetable to schedule two dedicated emergency DSU lists per week. Additional lists are provided on an ad-hoc basis when available. More recently, surgical specialties have sub-specialised limbs of this pathway. Since the end of 2019, an additional urology ‘hot list’ is also regularly timetabled to deliver definitive management of kidney stones within NICE recommended time frame.

Identifying data retrospectively for this pathway was challenging because all emergency cases were initially added to a single emergency ‘e-pool’. We separated those intended as day case emergencies by firstly searching the ‘Galaxy’ theatre system for all emergency cases who were admitted to DSU on the day of their surgery. A further ‘Galaxy’ search found emergency cases who were operated on in our main theatres from an inpatient ward but sent to DSU for secondary recovery as per the day case pathway. The pathway was further refined by the creation of a separate ‘ambulatory emergency’ pool to separate patients at the point of booking onto a day case or inpatient pathway. This is best practice for elective day surgery and is essential to achieve high quality day surgery Replicating this for emergency surgery has improved our pathway by clearly identifying those patients who are being considered for Ambulatory Emergency Care and ensuring that they are scheduled at an appropriate time and in an appropriate location.

Opportunistic streamlining of acute surgical inpatients

Surgical or anaesthetic teams may opportunistically identify existing inpatients who are suitable for discharge on the same day as their emergency surgery. They can undergo their surgery in any theatre before being discharged via DSU. We have seen a change in theatre culture, where day surgery teams with ad hoc gaps will contact the on-call team looking for ‘day case emergencies.’ Teams proactively identify any day surgery list which might finish ahead of schedule so that timely co-ordination with on the on-call team allows pulling a suitable case off the emergency list.

When looking at data for this cohort, patients will have a LOS of more than 0 days on account of their admission. Therefore, we have looked at whether they are discharged on the same day as their surgery.

Results

Evaluation

Abscess pathway

In 12 years, a total of 1831 patients underwent incision and drainage of an abscess. In 2019, 61% (113) of patients had a length of stay of 0 days. A further 12 patients were discharged on the same day as surgery, saving a total of 125 postoperative bed days in one year (Table 2). Our day case rate saw a steady increase from 2008, with a peak of 70% in 2015 before its plateau (Graph 1). On the day after their operation 90.5% (420/464) reported feeling ‘good’ or ‘very good’ with 87.2% (402/464) having no pain or mild discomfort only. Only 3% of patients felt nauseated, with 3 cases (0.6%) of reported vomiting.

Surgical management of miscarriage

There were 1540 cases in 12 years, with 1102 (72%) successful planned day case emergencies. Overall, 80% of women were able to go home on the same day as their surgery (Table 3). Over 12 years the day case rate has usually been high (peak 82%) but shows variability and a recent decline to 55% (Graph 2). The number of patients admitted has not changed dramatically but there has been an overall reduction in the number of cases managed surgically (83 patients, compared with a mean of 140 per year in the last 10 years). It appears more women are opting for medical management and there is also a proportion of patients who are able to have MVAs in outpatient clinic. This may support a trend of healthcare services moving into the outpatient setting and unburdening acute hospitals. The patients who have moved “down the intensity gradient” to the outpatient clinic would all be patients who were previously managed via a day case pathway. This reflects an improved service for these patients but may initially result in “apparent” reduction of the percentage of patients managed via a day case pathway. Notes review of the patients who required admission during 2019 revealed they were clinically unstable with many requiring blood transfusion. The day after surgery 86.2% (293/340) of women reported feeling ‘good’ or ‘very good.

Planned ambulatory emergency

Between April 2017 and January 2019 (22 months) 442 patients (18 children, 424 adults) underwent emergency surgery via this pathway. It freed 386 hours of emergency theatre time. There was a wide range of surgical specialities (Graph 3) with the majority of cases being general surgery, obstetrics and gynaecology or trauma. 370 patients (83.7%) were successfully discharged on the day of surgery and 301 patients (68.1%) avoided a pre-operative night stay. This saved 671 bed days with estimated cost of £268,400. The day after surgery, 90% of 257 patients (58.1%) followed up by telephone reported feeling ‘good’ or ‘very good’.

Using this pathway, surgeons have been able to successfully plan emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomies, appendicectomies and gynaecological laparoscopies as day cases. The pathway’s impact can further be evaluated by looking at all emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomies and appendicectomies that have taken place since its introduction in 2017 (Table 4 and 5). The proportion of patients with a LOS of 0 or discharged on the same day as surgery is on the rise. The BADS directory of procedures sets a target of 25% for emergency laparoscopic cholecystectomies. While our true day case rate in 2019 was 19%, when including those who are discharged on the same day of their surgery this increases to 30% (Table 4). Features of successful discharge were being admitted to DSU on the day of surgery, having surgery in the morning and being operated on by a consultant surgeon. Of those who were already inpatients 75% required admission following surgery. Consultant anaesthetist presence did not appear to influence discharge rates nor did the type of anaesthetic.

Opportunistic streamlining of acute surgical inpatients

We identified inpatients who underwent emergency surgery in any theatre and were sent to DSU after primary recovery. There were 141 patients over 22 months (April 2017 to January 2019) and 75% were discharged on the same day as their surgery. Opportunistic emergency surgery took place in every operating theatre, optimising efficiency and resulting in patient discharge.

Discussion

Ambulatory emergency surgery should be considered as an option at any stage of a patient’s journey. At Torbay hospital it is successfully facilitated through a number of pathways with a common goal. Ideally admission is avoided altogether but appropriately selected inpatients are streamlined to save post-operative stays.

Pathways can be tailored to serve individual patient groups or presenting conditions. Engaging the relevant stakeholders is key. A champion on the upper GI team has motivated others and the enthusiasm has spread to the urology team. The benefits are clear; reduced bed days, freed emergency theatre hours, increased patient satisfaction and better staff morale. DSU staff fed back that they feel they are offering a good service to patients using the day case emergency pathway. Data supporting this message can be presented to hospital management to push back against ‘bedding’ DSU spaces during times of bed crisis. It shows the DSU needs to remain running, not only to keep on top of elective waiting lists but also to relieve pressure from the acute hospital. Where there is no standalone unit, an acute medical or surgical unit could function as part of a day case emergency pathway. The pathway currently relies on individuals to co-ordinate and we are exploring the possibility of a day case emergency coordinator to work in a role that is similar to a trauma coordinator.

Day case emergency surgery has proved to be sustainable as seen in the last decade’s data and its scope continues to broaden. The authors believe up to 75% of the acute surgical take has the potential to be undertaken as day case surgery when there is a robust day surgery pathway.

References

- NHS digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care. nhs.uk

- Mayell AC, Barnes SJ, Stocker ME. Introducing emergency surgery to the day case setting. Journal of One Day Surgery 2009; 19:10–13.36.

- Bailey C, Ahuja M, Bartholomew K, Bew S, Forbes L, Lipp A, Montgomery J, Russon K, Potparic O, Stocker M. (2019). Guidelines for day‐case surgery 2019: Guidelines from the Association of Anaesthetists and the British Association of Day Surgery. Anaesthesia. 10.1111/anae.14639.

- Bamber JR Stephens TJ, Cromwell DA, Duncan E, Martin GP, Quiney NF, Abercrombie JF, Beckingham IJ. Effectiveness of a quality improvement collaborative in reducing time to surgery for patients requiring emergency cholecystectomy. BJS Open 2019. 3:802-811. https://doi.org/10.1002/bjs5.50221

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37933/302-can-we-extend.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse5

Dr Naomi Ward1, Professor Anil Hormis2

- ST3 trainee in Anaesthesia, The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, Moorgate Road, Rotherham S60 2UD

- Consultant in Anaesthesia and Critical Care, The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust, Moorgate Road, Rotherham S60 2UD

Corresponding author: naomi.ward@doctors.org.uk

In 2019 the Enhanced Recovery after Surgery (ERAS) group published a consensus statement on the perioperative care of patients undergoing lower limb (hip and knee) arthroplasty. (1) Recommendations were formulated by a multi- disciplinary panel of experts in ERAS pathways using a variety of sources and published guidelines from literature searches. We have summarised the guidelines below.

Preoperative care

Patient preparation

Patients should routinely receive preoperative education; this has been shown to reduce patient anxiety, despite not independently affecting postoperative outcomes. (1) There is strong evidence for this intervention. This should be an essential and compulsory component of ERAS pathways, if day case arthroplasty is being considered.

There is some evidence for optimising modifiable patient risk factors. In particular, smoking cessation for at least 4 weeks prior to elective lower limb arthroplasty is associated with fewer adverse outcomes; there is strong evidence for this intervention. (1) There is equally strong evidence for the use of alcohol cessation programmes in patients with high alcohol intake. (1)

Preoperative anaemia should be identified, investigated and corrected prior to surgery; there is strong evidence that this reduces postoperative blood transfusion, readmission and critical care admission, length of stay and overall costs. (1)

Preoperative physiotherapy has been suggested as an intervention to encourage early discharge; there is currently no strong evidence to support this as a recommendation. (1) It may, however, be beneficial in certain patient groups such as the elderly, and those with multiple comorbidities or frailty.

Preoperative fluid and fasting guidance

The intake of clear fluids up until 2 hours before surgery is strongly recommended in conjunction with a 6 hour fast for solid food. (1) This has been shown to have no effect on complication rates and as such is strongly recommended. (1)

The use of carbohydrate loading drinks has been shown to have mixed results; although used other types of major surgery, it is not currently recommended in lower limb arthroplasty patients as an essential routine intervention. (1)

Intra operative care

Anaesthetic considerations

A core component of ERAS pathways is a standardised anaesthetic protocol. In many hospitals, these differ and they are hard to compare.

Choice of anaesthetic technique

The avoidance of routine use of anxiolytic premedication is strongly recommended; this may however be necessary in certain patient groups to facilitate interventions. (1) This would be of particular importance if day case arthroplasty is being considered.

In terms of choice of modern general versus regional anaesthesia, there is no evidence to suggest the routine use of one over the other. (1) However, it is strongly recommended to avoid the routine use of spinal opioids due to concerns over the risks of urinary retention, pruritis and respiratory depression. (1) Similarly, despite the benefits in terms of excellent postoperative analgesia, it is strongly recommended to avoid the routine use of epidural analgesia due to the side effect profile. (1)

Prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV)

It is strongly recommended to risk stratify patients for PONV prior to surgery and to treat with escalating classes of antiemetic depending on their risk score. (1) A risk calculator such as the Apfel score can be used; current recommendations are for those with 1-2 risk factors to receive 2 antiemetics from differing drug classes, and in those at higher risk, 3 drugs from differing classes. (2)

Prevention of perioperative blood loss

The use of tranexamic acid (TXA) is strongly recommended to reduce perioperative bleeding and hence the need for perioperative blood transfusion. (1) Studies have found TXA to be safe despite perceived risks of increasing rates of venous thromboembolism (VTE). (3)

Analgesic strategies

In general, the use of multimodal analgesia is recommended as a vital part of ERAS pathways. In particular, the routine use of paracetamol is strongly recommended; as well as reducing postoperative pain scores with a favourable side effect profile, it has also been shown to reduce the incidence of PONV. (1)

The use of non-steroidal anti- inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) is strongly recommended routinely in patients with an absence of contraindications. (1) Patient groups in whom these drugs should be avoided include those with bleeding tendencies, peptic ulcer disease and renal or hepatic dysfunction.

Gabapentinoids are not currently recommended as part of multimodal analgesia in lower limb arthroplasty; there is a need for further study to evaluate their use. (1)

Despite ERAS programmes in general aiming to keep to a minimum the use of opioids, it is strongly recommended to use them when required as part of the multimodal analgesia programme. (1)

Local anaesthesia

Local anaesthetics can be used both in peripheral nerve blockade and for local infiltration analgesia (LIA). One advantage of LIA over nerve blockade is the avoidance of motor block and hence earlier postoperative mobilisation. This technique is strongly recommended in arthroplasty of the knee, but there is not currently little evidence to suggest its use in hip arthroplasty patients. (1)

Due to the above-mentioned risk of prolonged motor blockade, nerve block techniques are not currently recommended in ERAS lower limb arthroplasty patients. (1)

Other anaesthetic considerations

The maintenance of normothermia is an important component of ERAS pathways. There is a high level of evidence for this, with the UK’s National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) recommending pre- warming and then active warming for all patients undergoing surgery. (1) It is therefore strongly recommended that normothermia is maintained in this way. (1)

Postoperative joint infection in patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty is a potentially catastrophic outcome that is difficult to treat. As a result, it is strongly recommended that this patient group receives suitable antimicrobial prophylaxis in line with local guidelines. (1)

Hip and knee replacement surgery is associated with an increased risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). (1) It is therefore strongly recommended that patients are mobilised as soon as possible postoperatively and receive prophylactic treatment according to local guidelines in order to reduce this risk. (1)

Fluid management is an important component of anaesthetic practice. It is strongly recommended that intraoperative fluids are used judiciously, but that they should be discontinued early to allow resumption of oral fluid intake. (1) Electrolyte abnormalities (eg) hyponatremia should be avoided by using intravenous fluids to replace insensible losses only. (1)

Surgical considerations

Differences in surgical technique have been studied as to their potential effect on discharge and complication rates. There is currently no evidence to suggest any one surgical technique as part of an ERAS pathway. (1)

Tourniquets have historically been used in knee arthroplasty to reduce intraoperative bleeding; it has however been demonstrated that this does not reduce total blood loss and may hamper early postoperative recovery. (1, 4) As a result, the avoidance of routine use of tourniquets is strongly recommended. (1) Likewise, the avoidance of routine use of surgical drains is strongly recommended due to the increased risk of blood loss. (1)

The routine use of urinary catheters is not recommended in ERAS patients undergoing lower limb arthroplasty. (1) Where these are necessary, the aim should be to remove as soon as the patient is able to pass urine, and ideally within 24 hours of surgery. (1) Postoperatively, a bladder volume threshold of 800ml should be used to indicate the need for urinary catheterisation. (1)

Postoperative care and discharge

Return to normality is an essential part of ERAS protocols and this encompasses early return to oral nutrition. It is strongly recommended that patients are encouraged to resume normal eating and drinking as soon as possible. (1) There is good evidence for early postoperative mobilisation; it is strongly recommended that this is promoted. (1)

Discharge criteria are an important component of the ERAS pathway and it is strongly recommended that units have a set of objective discharge criteria. (1) They may include the ability to self- care, toilet and dress oneself and independently mobilise. (1)

Conclusion

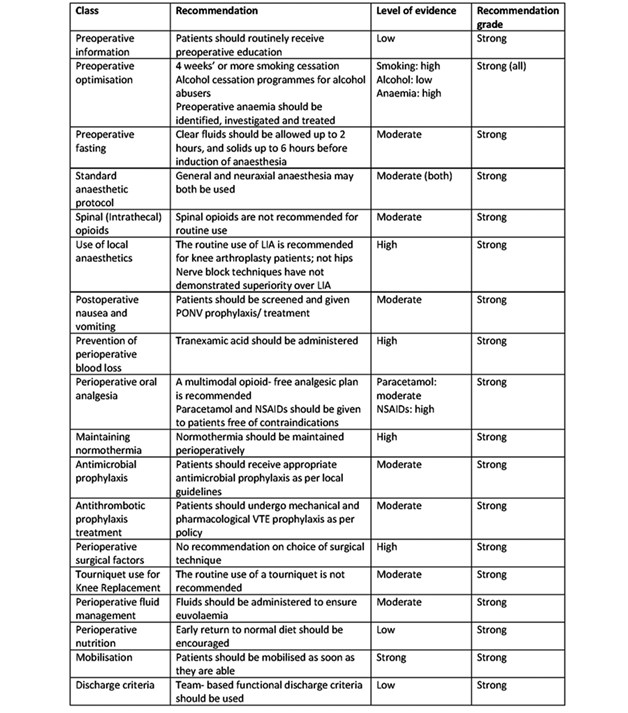

This is a summary of the recommendations from the ERAS Society on the perioperative management of patients undergoing hip and knee replacement surgery. A summary of all the recommendations and the grade of evidence can be found in Table 1. The guidelines are an attempt to summarise a wide range of heterogenous protocols in the literature. We would urge colleagues to read the entire guidance and consider implementation of these components in their ERAS pathways within their arthroplasty units. The aim should be to decrease length of stay (LOS) and in some cases, potentially aim, for day case hip and knee arthroplasty.

Table 1. Summary of ERAS society guidelines for lower limb arthroplasty. Adapted from (1).

References

- Wainwright T, Gill M, McDonald D et al. (2019): Consensus statement for perioperative care in total hip replacement and total knee replacement surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS®) Society recommendations, Acta Orthopaedica, 2019, DOI: 10.1080/17453674.2019.1683790.

- Gan T, Diemunsch P, Habib A et al. Consensus guidelines for the management of post operative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2014 Jan;118(1):85-113. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000000002

- Fillingham Y, Ramkumar D, Jevsevar D et al. The safety of tranexamic acid in total joint arthroplasty: a direct meta- analysis. J Arthroplasty. 2018 Oct;33(10):3070-3082.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2018.03.031.

- Zhang, W., Li, N., Chen, S. et al. The effects of a tourniquet used in total knee arthroplasty: a meta-analysis. J Orthop Surg Res 9, 13 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1749-799X-9-13.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37934/302-perioerative-care.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse6

Dr Gregory Warren, Core Trainee in Anaesthesia, Dr Jonathan Carter, Core Trainee in Anaesthesia; Dr Alexandra Humphreys, Specialist Registrar in Anaesthesia; Dr Mary Stocker, Consultant Anaesthetist

Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Torbay, United Kingdom

Corresponding author: Dr Gregory Warren, Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Newton Road, Torbay, TQ2 7AA, United Kingdom.

Keywords: Day surgery; pathway; admission; patient journey

Acknowledgements: The authors gratefully acknowledge advice on statistical analysis provided by Dr John B Carlisle.

Abstract

Introduction: Patients undergoing day case operations in our trust are managed via one of two pathways:

- Admission, surgical procedure, recovery and discharge all in dedicated Day Surgery Unit (DSU)

- Admission, surgical procedure and first stage recovery via main inpatient theatres (MT), then transfer to DSU for second stage recovery and discharge.

We aimed to establish the difference in time taken for patients to undergo the same operation via each of the two pathways.

Methods: Three routine elective operations were monitored: laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC), laparoscopic hysterectomy (LH), and open repair of inguinal hernia (IH).

The entire patient journey was observed. The time that each patient spent at each stage, and any delaying factors, were noted.

18 patient journeys were monitored in total, 3 of each procedure (LC, LH and IH) through both DSU and MT pathways.

Results: The median time taken for the majority of steps in the pathway was shorter in the patients on the DSU pathway.

Median time taken from send to arrival in secondary recovery (hr:min): DSU 02:46. MT 03:32. Difference 00:46

Conclusions: Managing patients in a dedicated DSU results in a shorter surgical pathway for the patient. This is beneficial for the patient and has associated financial savings for the trust. The increased turnover should enable more patients to be managed on an individual list.

Introduction

Torbay Hospital is one of the top performers nationally in terms of day surgery rates, variety of day case procedures and clinical outcomes. It currently ranks in the top quartile nationally for trust level day case rates based on British Association of Day Surgery benchmarking data1.

The dedicated Day Surgery Unit (DSU) manages the majority of day case work and follows national recommendations for day surgery 2. This pathway enables patients to undertake their entire day surgery pathway (pre-operative assessment, preparation, surgical admission and discharge) within the same unit, cared for by a team of day surgery professionals.

The trust performs approximately 17,000 day case procedures per annum. Approximately 60% of these cases are managed via the dedicated DSU. The remaining 40% of day cases are managed via main theatre (MT) pathway, due to lack of a capacity or lack of clean air facilities in the DSU.

Day of surgery pathways:

DSU pathway:

Patients present to the DSU upon arrival in the hospital, whereby they are ‘checked in’ for surgery. Upon being ‘sent’ for, patients walk to theatre (a distance of only a few meters), where the procedure is undertaken. Patients are then transferred to primary recovery. Upon meeting the discharge criteria to exit primary recovery, patients progress to secondary recovery. Patients are discharged home from secondary recovery.

The DSU is an integrated self-contained unit, located on one level. Each step in the process requires a distance of mere metres to be travelled.

Main theatre pathway:

Patients present to the main inpatient surgical pre-operative ward, where they are ‘checked in for surgery’. Upon ‘sending’, patients are checked out of the ward, and escorted down two stories via a lift, to main theatres. On completion of the procedure, patients are transferred to main theatre recovery. When patients meet the discharge criteria to exit main recovery, a porter is summoned, and the patients are transferred down three stories via a lift, through the Emergency Department, to the DSU secondary recovery. Patients are again discharged home from secondary recovery.

The aim of this piece work is to evaluate the efficiency of patient flow through our dedicated DSU, compared to undergoing day case procedures via main theatres.

Methods

Three different day case procedures that are performed in both main theatres and the DSU were selected; laparoscopic cholecystectomy, inguinal hernia repair, and laparoscopic hysterectomy. 3 patients undergoing each procedure on each pathway were randomly selected to be followed (n=18, 9vs9). Patients were allocated to the two pathways as normal, by the theatre booking team who were unaware of the project. An auditor followed each patient throughout the entirety of their patient journey, from presentation on the pre-operative ward, to arrival at second stage recovery. During each case, contemporaneous timings were recorded at specific intervals in the patient journey. Qualitative information on delays was documented.

The patient journey was defined as time from ‘send’ to time of arrival in second stage recovery.

Time from arrival on the preoperative ward to send would vary depending on position on list and was therefore omitted.

The recorded data was analysed using a data spreadsheet programme and statistical analysis was performed via analysis software R and SPSS.

Results

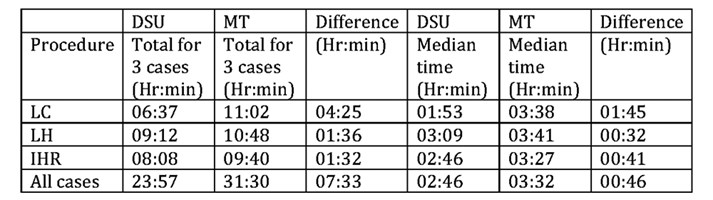

Table 1. Duration of patient journey.

- Defined as time from send to arrival in secondary recovery.

- A Mann-Whitney U test was performed, comparing total duration of patient journey across all three case types between DSU and MT (n=9 v 9):

- p = 0.002 with median (interquartile range [range]) times(mins) of:

- DSU 166 (146-177 [107-205])

- MT 212 (207-221 [162-242])

If we take the Bayesian view of probability, these results would generate the belief that MT total time is 50 minutes longer than DSU time with a 95% credible interval of 18-90 minutes.

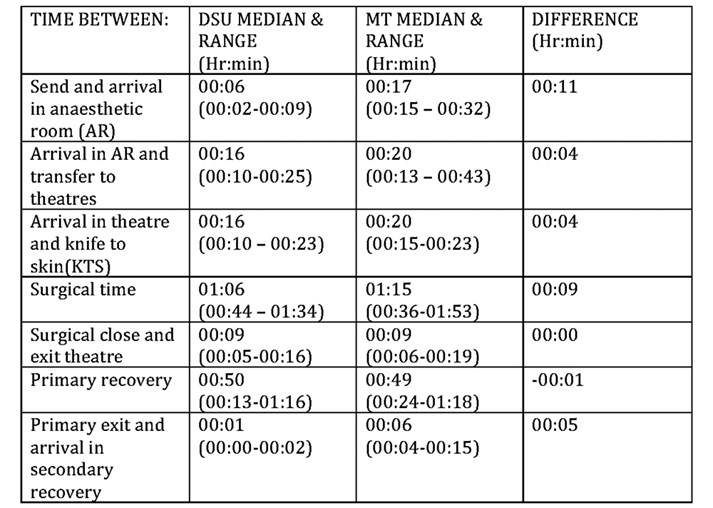

Table 2. Interval timings.

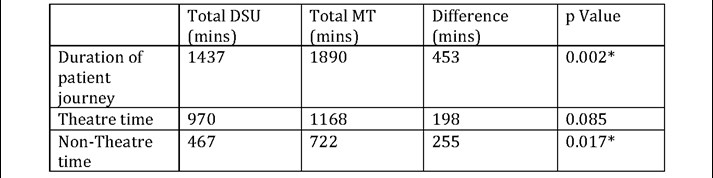

Table 3. Theatre time (arrival in anaesthetic room to exit operating theatre) vs non-theatre time

(Patient journey minus theatre time) for all cases (n=9:9).

A Mann-Whitney U test was used to compare theatre and non-theatre times across both pathways.

Efficiency Gains (Based on estimated running costs)

Despite not achieving a significant difference (p=0.085) between pathways, the following has been included to demonstrate the organisational benefits conferred by saving theatre time.

Theatre time running costs for 9 cases:

- DSU = £12 per minute

- 970 x 12 = £11640

- Main Theatres = £15 per minute

- 1168 x 15 = £17520

- Theatre time efficiency gain = £5880 across 9 patients

Non-theatre time saved per patient

- Difference in non-theatre time/number of patients on DSU pathway

- 255/9 = 28 mins of staff contact time per patient.

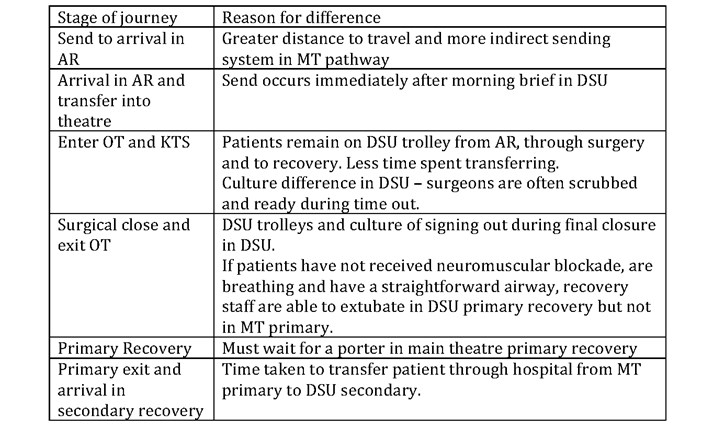

Table 4. Subjective reasons for time differences in various stages of the patient journey.

Discussion

The data obtained demonstrates a faster total transit time through a dedicated DSU when compared with a day surgery pathway through main theatres (p=0.002). It also suggests a faster time through most elements of the patient journey. This confers an efficiency gain which can be described in terms of duration, finances, cases per list or staff contact time.

There are many organisational, cultural and logistical factors underlying the difference in performance. Table 5 highlights some of the reasons identified during direct observation but overarching key differences include:

Ergonomics of clinical area

The design and layout of the day surgery department allows theatre staff to move patient’s short distances by foot or on trolleys without requiring a porter. All clinical staff are working close by so recovery and pre op staff can attend the morning safety brief. Any issues or hold ups can be clearly communicated face to face and resolved more efficiently. When sending for a patient, the ODP physically takes a send form and walks it down the corridor to locate the HCA who then collects the patient. This is in contrast to a semi-automated system where a send form is printed in the MT surgical admissions unit and the patient is brought down when the form is collected by an available staff member. Post-operatively, rather than a seven-minute transfer through the hospital from MT primary to DSU secondary recovery, it is a matter of pushing a patient through double doors from DSU primary to secondary. In reality this gives recovery staff more confidence to transfer to secondary recovery earlier in day surgery.

Day surgery trolleys

In the DSU, patients walk from the waiting area to anaesthetic room and sit on the day surgery trolley. They will then stay on this trolley for their anaesthetic, surgery and recovery. Add-ons in theatre such as arm boards, lithotomy stirrups and shoulder supports along with trolley functionality enable patient positioning to cover all current day case procedures. This saves on transfer time and helps reduce intra operative heat loss and post-operative nausea and vomiting associated with repeated rolling and patient transfer.

Culture

Torbay hospital’s day surgery unit is staffed with specific day surgery nurses, ODPs, HCAs and administrative staff. It has ownership of its preoperative assessment and post-operative follow up pathways and has a strong culture of continuous audit and quality improvement whilst pushing the boundaries of current day surgery practice with procedures such as hip, knee, shoulder replacements and nephrectomies. This has led to a group of workers who are experts in helping patients navigate each part of the pathway and who are motivated to keep admission rates low.

Admission Documentation

Patients on the MT pathway experience a different admission process to those on the DSU pathway. Our inpatient admissions unit have a culture of repeating patient observations on admission (blood pressure, heart rate and oxygen saturations). The policy in DSU is that these only need to be checked if a problem was identified at the preoperative assessment clinic. In addition, patients on the MT pathway require duplication of paperwork as more detailed “inpatient pathway” paperwork is expected for patients attending the MT complex. The combination of these results in significant increase in the time taken for the nurse based admission process and often delays the surgical and anaesthetic staff who have to wait for this to be completed prior to being able to visit the patient pre-operatively.

Whilst the number of patients and type of procedure reviewed is a limitation of this project, it reflects the resource intensive nature of contemporaneous data collection; over 55 hours on data collection alone. Expanding on the numbers and procedure type may highlight true differences in system performance (e.g. shorter theatre times) which are distorted by potential outliers in this data set.

As this is an observational study rather than interventional, it is open to a range of confounding factors, some of which are highlighted below.

The patients in each group were not matched for comorbidity or surgical complexity and there was no retrospective analysis or post hoc correction. The patients were allocated by theatre booking staff who do not take patient characteristics into account during the booking process. Underlying differences in complexity of cases may have contributed to lengthen the theatre time of either DSU or MT pathway patients which in turn would have impacted on the observed difference. Other confounding factors may include, type of anaesthetic, experience of staff, teaching and training. It has previously been demonstrated that the same operation, using the same surgeon and anaesthetist takes less theatre time in Torbay’s dedicated DSU when compared to MT3. It is therefore plausible that the above factors may have masked a significant difference in theatre time.

Improving the efficiency of the MT pathway may be achieved by applying the learning from observation of the equivalent pathway in a dedicated DSU. A proportion of unproductive time is due to the distance between admissions, theatres and secondary recovery. This may be difficult to overcome. A main theatre discharge lounge has previously been trialed but resulted in increased admission rates. It may be possible to increase the use of day surgery trolleys in the MT pathway and work on specific aspects of staff culture to reduce theatre time. Expanding the day surgery unit to take a larger proportion of day surgery procedures may well increase capacity and efficiency and would be a possible long term plan.

Conclusion

National guidelines recommend day surgery cases should occur in a dedicated day surgery unit and our experience supports this.

Patients undergoing the same procedure via a dedicated Day Surgery Unit experience a shorter pathway and require less 'staff time,’ potentially resulting in a reduced financial burden to the trust.

References

- The Model Hospital. NHS Improvement. https://improvement.nhs.uk/resources/model-hospital/ Accessed on 18th February 2020.

- Royal College of Anaesthetist. Guidelines for the provision of anaesthesia services for day surgery, 2019. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/gpas/chapter-6 (Accessed 14th January 2020)

- Dione T, McCarthy R, Stocker ME. The financial argument for day surgery; illustrated using inguinal hernia repairs. J One Day Surg. 2008:18S.

Funding: None declared

Conflict of interest: None declared.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37935/302-benefits.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse7

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf

from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37930/bads-general-surgery-sept-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse9

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf

from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34969/bads-day-case-major-knee-surgery-oct-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse10

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf

from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34971/bads-day-case-hip-nov-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse11

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference or download the pdf

from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/34973/bads-day-surgery-gynaecology-nov-2020.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse12

General Guidelines

The Journal of One-day Surgery considers all articles of relevance to day and short stay surgery. Articles may be in the form of original research, review papers, audits, service improvement reports, case reports, case series, practice development and letters to the editor. Research projects must clearly state that ethics committee approval was sought where appropriate and that patients gave their consent to be included. Patients must not be identifiable unless their written consent has been obtained. If your work was conducted in the UK and you are unsure as to whether it is considered as research requiring approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), please consult the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool at http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Articles should be prepared as Microsoft Word documents with standard line spacing and normal margins. Submissions must be sent by email to the address below.

Copyright transfer agreement and submission

As of 7th November 2019, the JODS copyright transfer agreement must be downloaded from the resources section (tab) via the BADS website:

https://daysurgeryuk.net/en/resources/documentation/

Each named author should complete and sign a copy. Scanned copies/legible photos should be sent via email together with the main manuscript to the JODS editor: davidbunting@nhs.net

Any source of funding should be declared and authors should also disclose any possible conflict of interest that might be relevant to their article.

Submissions are subject to peer review. Proofs will not normally be sent to authors and reprints are not available.

Manuscript preparation

Title Page

The first page should list all authors (including their first names), their job titles, the hospital(s) or unit(s) from where the work originates and should give a current contact address for the corresponding author.

The author should provide three or four keywords describing their article, which should be as informative as possible.

Abstract

An abstract of 250 words maximum summarising the manuscript should be provided and structured as follows: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions.

Main article structure

Manuscripts should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and References. Tables and figures should follow, with each on a separate page. Each table and figure should be accompanied by a legend that should be sufficiently informative as to allow it to be interpreted without reference to the main text.

All figures and graphs are reformatted to the standard style of the journal. If a manuscript includes such submission, particularly if exported from a spreadsheet (for example Microsoft Excel), a copy of the original data (or numbers) would assist the editorial process.

Copies of original photographs, as a JPEG or TIFF file, should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedding pictures within the text of the manuscript.

Tables, Figures and Graphs

Please submit any figures, graphs and images as separately attached files rather than embedding non-word files into the word manuscript document. Tables constructed in MS Word can be left in their original MS Word file including the manuscript if this is where they were drawn.

Figures and graphs can be presented in colour but try to avoid 3-d effects, shading etc. Figures and graphs may be redrawn if the quality is not in keeping with the Journal. Please make it clear within the manuscript text where you would like tables, graphs or images to be placed in the finished article with the use of a brief explanatory legend in the manuscript file where you wish the item to be placed, e.g.

Table 1. Patient demographic details.

Figure 1. Proportion of procedures performed as a day-case each year between 2005 and 2018.

Photographs

Photographs can be provided as jpg or tiff files but should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedded within the text of the manuscript. This ensures higher quality images. However, we will accept images within Word documents but image quality might suffer!

References

Please follow the Vancouver referencing style:

- References in the reference list should be cited numerically in the order in which they appear in the text using Arabic numerals, e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4 etc.

- The reference list should appear at the end of the paper. Begin your reference list on a new page and title it 'References.'

- Cite articles in the manuscript text using numbers in parentheses and the end of phrases or sentences, e.g. (1,2)

- Abbreviate journal titles in the style used in the NLM Catalogue: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog?Db=journals&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=currentlyindexed%5BAll%5D

- The reference list should include all and only those references you have cited in the text. (However, do not include unpublished items such as correspondence).

- Check the reference details against the actual source - you are indicating that you have read a source when you cite it.

- Be consistent with your referencing style across the document.

Example of reference list:

- Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281.

- Dybvig DD, Dybvig M. Det tenkende mennesket. Filosofi- og vitenskapshistorie med vitenskapsteori. 2nd ed. Trondheim: Tapir akademisk forlag; 2003.

- Beizer JL, Timiras ML. Pharmacology and drug management in the elderly. In: Timiras PS, editor. Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. p. 279-84.

- Kwan I, Mapstone J. Visibility aids for pedestrians and cyclists: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(3):305-12.

- Barton CA, McKenzie DP, Walters EH, et al. Interactions between psychosocial problems and management of asthma: who is at risk of dying? J Asthma [serial on the Internet]. 2005 [cited 2005 Jun 30];42(4):249-56. Available from: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/.

Mr David Bunting

Editor, Journal of One Day Surgery

Consultant Upper GI Surgeon

North Devon District Hospital

[These guidelines were last revised on 02.11.2019]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/37293/author-guidelines.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=1968#collapse14