Dave Bunting

Taking the opportunity to reflect on the success of the recent BADS Virtual conference, for those of you that did not manage to attend the event, this edition of JODS includes a report for the conference by Fiona Belfield. This edition also features a number of reports recently published in the Clinical Services journal (CSJ). I would like to take this opportunity to thank the CSJ for allowing us to reproduce their work. They offer a report on delivering day surgery as default, reflecting on work presented at recent virtual conferences including the BADS/HCUK Day Case Major Knee Surgery event. Their next article highlights some of the issues raised at the BADS Virtual conference held in March and focussed on how day surgery can be used to recover elective surgery. The also published a report on how waiting lists can be managed in the Covid-19 era, identifying day surgery as a very important part of this agenda. Finally, included is an interesting article raising an important issue relevant to surgical practise as much as any NHS domain. This addresses workforce burnout in the NHS and how this can be tackled.

This edition of JODS includes a report identifying reasons for increased length of stay in patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy patients; a service evaluation into paediatric fasting times and the results of a topical survey on patients’ attitudes towards Covid-19 safety precautions.

Please keep your submissions to the journal coming in and remember – JODS still offers citable peer-reviewed publication with no author processing fees. Updated author guidelines and submission instructions can be found in this edition of the journal.

Whilst JODS has been enjoying the relatively new format of electronic publishing with the obvious benefits this brings to its readers, it’s time for a shake-up to modernise the look and provide a broader range of content. The next edition of JODS is due for publication in November and promises to deliver enhanced figures/graphics in addition to new features that may include interviews with experts in the field of day surgery, puzzle/quiz corner and more…watch this space!

Finally, it is a pleasure to welcome Jo Marsden, our new BADS President to JODS. Her first President’s letter in this edition of the Journal demonstrates her passion for driving the day surgery agenda and for continuing to raise the profile of BADS, building on recent successes of the excellent virtual conference and an increase in the BADS membership numbers across all member categories.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52459/312-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse0

Jo Marsden

Last but not least, is the fact that BADS public profile is growing as reflected in the expansion of collaborations with other organisations, who realise the importance of day surgery in the recovery of surgical services. Membership has increased in parallel, which is fantastic and will only strengthen our purpose further.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52473/312-pres.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse1

British Association of Day Surgery Virtual Conference

Thursday 18th March 2021

“Using day surgery to recover elective surgery in the era of Covid-19”

Reflections of the day

It was with a heavy heart, but we knew it was the responsible course of action to cancel our face-to-face meeting, which was first planned for June 2020, then re-arranged for March 2021 due to the Covid -19 pandemic and organise a virtual conference. This was new territory for BADS, and we approached it with trepidation.

The day of the conference came quickly, and we were absolutely delighted to have had a record number of delegates, nearly 400 from around the world registering for our 1st virtual conference.

The conference commenced with Dr Kim Russon President of BADS welcoming delegates and promising a full day of high calibre lectures and speakers, with a wide range of specialities all speaking on their experiences in managing the re-commencement of day surgery following the Covid-19 pandemic.

The first session was delivered by Professor Tim Cook, Consultant in Anaesthesia, and Intensive Care Medicine, at Royal United Hospital, Bath who spoke about “Covid -19 and the challenges facing elective surgery.”

This session was well received and generated lots of discussion on the challenges facing the NHS. The main message from Professor Cook was that recovery from Covid-19 is going to be a marathon and not a sprint. He also emphasised that elective surgery could only resume when there is physical space available, staff have returned to substantive posts and most importantly staff wellbeing needs to be supported. This will require workforce planning at all levels and consider training needs for trainee doctors. Fundamentally, patients will require re-assessment due to potential change in a patient’s condition.

The second session was titled: “Why and how should you default to day surgery to maintain elective pathways” and delivered by Professor Tim Briggs, Chairman of the Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) programme and National Director of Clinical Improvement at NHSE and Dr Mary Stocker, Immediate Past President of BADS.

Professor Tim Briggs gave an overview of the work he is doing with GIRFT and the London recovery of elective surgery programme. This project has been very successful in increasing day case rates by setting a target of achieving 85%-day case rates across all specialities and standardising pathways. He summarised that if we are to achieve higher day case rates, we need something different and urgently. This will require utilising the GIRFT methodology, standardising pathways, refining theatre principles and improving day case patient flow.

Dr Mary Stocker followed by giving us an overview on day case pathways, how these should be developed and what should be included. She stressed the importance of the need to stretch the boundaries of day surgery; expand the range of procedures performed in the day surgery setting and widen patient selection criteria, if day surgery is to play a pivotal role in recovering elective surgery after Covid -19. Mary gave reference to the Model Hospital and the Day Surgery Delivery Pack; a collaboration with BADS and GIRFT. They are both excellent guides as to what can be achieved as day case. These resources give good practical advice and a platform to be able to network with day case units that perform well in certain procedures. She also emphasised that to achieve the best outcomes, day case units should be dedicated units with expert staff, have up to date equipment and a lead individual who will drive day surgery within their trust and standardise pathways. By implementing these trusts will be able to start to recover elective surgery with minimal impact on inpatient beds.

The third session was delivered by Dr Chris Snowden and Dr Mike Swart, both GIRFT National Clinical leads for Anaesthesia and perioperative medicine. They presented on “Variation in day case surgery: GIRFT Anaesthetics and perioperative medicine national report and reducing variation.” Dr Chris Snowden gave a detailed overview on the report. His principal message was that recovery of elective surgery is going to be slow and that we all need to be working collaboratively to achieve the best possible outcomes. He also concluded that day surgery should be accepted as the default for elective surgery and the importance of measuring day case data.

Dr Mike Swart presented and summarised the GIRFT pathways and the implementation of day case pathways. He emphasised the importance of such pathways, and that it is essential to start with primary care, working through to discharge. He focused on GIRFT gateways and the National Day Surgery Delivery Pack as integral tools to improve day case rates further in England. Once this has been achieved, GIRFT will start to look a pre-assessment, inpatient then emergency pathways, although he feels that this can only be achieved by continuing to work closely with BADS, Preoperative Centre for Perioperative Care, relevant associations, and colleges.

After the coffee break and a chance for delegates to view the posters and exhibition, it was back to business. Session 4 comprised the prize presentations, which I always enjoy listening to. This part of the conference highlights all the hard work and commitment of teams in driving day surgery forward. This year was no exception, the standard of all presentations was high with a record number of abstract submissions, 75 in total. We heard from 6 presenters selected for the prize session with specialities including: orthopaedic surgery, maxillofacial surgery and urology. We asked delegates to vote for the best presentation using the Slido facility and I am pleased to announce that First Prize was awarded to Lindsay Hudman, Glasgow Royal Infirmary, for her presentation “The Coronavirus Pandemic: A catalyst for the accelerated development of a successful new orthopaedic service in Glasgow.” Second prize was awarded to Nimlan Shanmugathas, Imperial College NHS Foundation Trust for his presentation on “Early Experience of Primary Transurethral water vapour treatment (Rezum ®) for symptomatic Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia: an analysis of 332 consecutive patients”. Congratulations and a big thank you to all the presenters in the prize session who spoke and provided the delegates with their thought-provoking and innovative work occurring across the UK.

This concluded the morning session with the afternoon session tailored to specific specialities and how these specialities managed to continue with operations during the constraints of the Covid-19 pandemic. The afternoon speakers demonstrated resilience and determination of teams that work within the NHS and commitment in providing the highest quality of patient care without compromising patient safety.

Five specialities were included in this session. The first speaker was Mr David Bunting, a Consultant Upper GI Surgeon working in North Devon District Hospital. He spoke about laparoscopic cholecystectomy and how they managed to reduce length of stay and increase day case activity by introducing a “Hot-gallbladder pathway” for patients presenting to the Emergency Department or via urgent GP referral. He concluded that although Covid-19 has been detrimental to elective services, the unique challenges have presented healthcare trusts with opportunities to develop new pathways that promise to delivery positive benefits for all patients in the long-term.

The second speciality was Gynaecology and Mr Peter Scott a Consultant Gynaecologist from Plymouth gave his talk on how his team succeeded in moving gynaecological procedures from a day theatre to out-patients. He gave an overview of the procedures that were moved to an outpatient setting and associated new pathways that have been developed. These include, Novasure Endometrial ablation, Myosure Morcellation, manual vacuum aspiration for miscarriages and surgical termination of pregnancy. He explained that moving these procedures into this environment is a more cost-effective way to manage these patients. Covid-19 has had a positive impact on services by taking opportunities to develop the service with shorter waiting times, freeing up theatre sessions, and reduced patients length of stays. Patient feedback from the introduction of this service has been very positive, outcomes have improved, and activity has increased significantly by adopting new ways of working.

The third presentation was on day case total hip replacement as a day case presented by Dr Claire Blandford, Consultant Anaesthetist from Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust. Key recommendations for introducing a successful total hip replacement pathway included looking at inpatient management and how this can be adapted to a day case pathway. She emphasised that the patient’s mindset should be positive and geared to go home the same day, encouraging this concept as soon as possible, ideally from pre-assessment. Creating targets to work towards and analysing data along with optimal peri-operative and post-operative management of pain, a robust standardised protocol, and a ridged discharge plan, should all be in place if day case hip replacements are to succeed. She also emphasised that networking with other units performing day case total hip replacements and learning from them can help them create a successful pathway. Torbay are achieving 94%-day case total hip replacements as present, which is very impressive.

The Maxillofacial session was delivered by Miss Francine Ryba, Consultant Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeon, from King’s College Hospital, London, and Mr James Douglas, registrar in Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, from Leeds Teaching Hospital. These presentations compared two different teams and how they set about creating a pathway for repair of fractured zygoma as a day case. It was interesting to hear two different reports of how, why and when their pathways were developed. King’s College commenced this pathway because of the Covid -19 pandemic, whilst Leeds Teaching Hospital has been successfully achieving these for 10 years. Both spoke that due to the length of time eye observations must be completed, as the risk of bleeding and compartment syndrome, make it more difficult to achieve as a day case, so both stated that these procedures should be completed on a morning list. There is ample time for these observations to be completed within the day. Although Mr James Douglas highlighted that when they were looking at past research, the incidence of this complication was relatively rare. The main conclusion from both units was that in order to achieve a successful pathway, there must be good teamwork and a dedicated pathway. Mr Jiten Palmer, a Consultant OMFS, from Leeds Teaching Hospital, joined in with the discussion following the presentations.

This led us to the final presentation in this session, which saw Mr Feras Al Jaafari talk about how he successfully changed the pathway of ureteroscopy from an inpatient to a day case. They commenced this change in 2018 due to inpatient bed pressures and theatre lists regularly being cancelled. The findings were positive, and they increased their day case rate to 85% when the procedure was moved into the day case setting compared to 17.6% in an inpatient setting. There was no change in re-admission rates or complications by performing this in a day case unit, which confirms that it is a safe procedure to perform in this setting. There was a significant financial saving with 28.2% to 50.3% reduction in costs by moving into a day case setting. This was also associated with a reduction in length of stay. He concluded by informing the delegates that they now perform 85.3% of ureteroscopies as day cases offering this pathway by default to all suitable patients. Importantly, the patient perception is key to ensuring patients are discharged on the same day.

There was a period of live discussions following each of the five presentations which provoked lots of questions and debate and keeping our moderators busy. These presentations were brief (15 minutes) but focussed, providing a detailed and informative insight into the innovative work being undertaken in our forward-thinking day surgery units throughout the UK.

This bought us onto our last session of a very full programme for our first virtual conference. It was the turn of pre-assessment to be presented and again we had two speakers who spoke about their experiences and challenges and how Covid-19 has changed their practice. Mrs Karen Harries, Lead Nurse for Day Surgery and Pre-Assessment at King’s College Hospital, London spoke first. Her presentation concentrated on her experiences of Covid -19 and how they had to change their practice and adapt to new ways of working, that ensured Covid -19 guidelines were followed but at the same time the patients were optimised for their operation. She shared the changes that were implemented quickly to maintain pre-assessment flow. For example, patients were pre-assessed via telephone prior to surgery and any pre-operative tests to be performed on the day of surgery. This limited the number of times the patient had to visit the pre assessment unit. They created a generic email, so anaesthetists that were shielding could review patients. The undertook a very small survey to see patients’ thoughts on the telephone assessment and unsurprisingly, the fit and well patients preferred this method but the patients who were not so fit did not feel comfortable with simply a telephone assessment. Karen concluded by sharing some of the good effects that came out of the Covid -19 pandemic, and they have now moved away from face-to-face for ASA 1 and 2 patients but will still manage the ASA 3 and 4 patients through video-link or face-to-face. They are looking to introduce community hubs within the community, so vulnerable patients can have tests performed without having to visit the main hospital.

It was then Dr Christina Beecroft’s turn to present. She is the Clinical Service Director in Elective Perioperative Care, working in Ninewells Hospital, Dundee. This presentation concentrated on the developing strategies on how best to manage safe elective surgery through the pandemic by developing a pre-surgery isolation pathway. They ask patients to isolate for 14 days prior to their surgery and the patients take a Covid-19 test on their first day of isolation, then a second one 48hrs prior to their surgery. Even though the timescale is short to optimise these patients, they have succeeded in the management of these patients. This is down to the determination and commitment of the team and collaboration and communication between different departments. One aspect they will continue are the regular meetings with the waiting list team to optimise scheduling in advance. This ensures good communication with all involved in scheduling patients and an opportunity to discuss any potential problems and offer solutions working in a collaborative manner.

Dr Kim Russon, President of BADS, drew our conference to a close, and thanked all the presenters for their input into a full day of excellent presentations. She recognised all the good work that is being achieved throughout the UK and was encouraged by the active participation of delegates on the day. They were enthusiastic in the chat and she hoped this would interaction would continue beyond the conference.

It just leaves me to mention the winners of the posters, and as ever there was a high standard of abstracts this year. With a record number of posters, 63 in total. We divided them into 4 categories and below are the winners from each category. Congratulations to all that submitted an abstract and we always encourage authors to submit their abstracts for consideration of publication in JODS. Details on how to submit an abstract can be found here:

jods-author-guidelines-april-2021.pdf (bads.co.uk)

Prize posters

Surgery category:

Mohammed Shaath, Northern Care Alliance, Manchester

7 years of Day Case Uni-compartmental Knee Arthroplasty for all-comers within the NHS: The journey and evidence of sustained change

Nurse/Management category:

Lewis Powell, Prince Charles Hospital, Merthyr Tydfil

Emergency Day case surgery to east pressures caused by Covid-19

Educational Grant category:

Ruth Burgess, Leeds Teaching Hospitals Trust

Pre-operative Communication in Day-Case Surgery: Patient views of text messaging and access to online information for elective day-case surgery

Anaesthesia category (5 joint winners):

Rebecca Janes, Nottingham University Hospitals

Perioperative care of inguinal hernia repair and length of stay

Rachel Heard, Royal Preston Hospital, Manchester

Paediatric Fasting Times Audit

Rory Colhoun, The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust

Successful Day Case Uni-compartmental Knee Replacement (UKR) at The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust

Victoria Peacock, Airedale General Hospital, West Yorkshire

Ensuring safe and timely discharge following spinal anaesthesia for Day case; creation of Nurse-led discharge criteria at Airedale General Hospital

Rachel Tibble, Royal Derby Hospital

The Effect of Centralisation of Preoperative Assessment on Day Surgery List Efficiency

Exhibition Competition

One final congratulation goes to Rachel Tibble, as the winner of the exhibition competition. Well done Rachel on working out the answer.

The correct answer was:

“Using day surgery to recover elective surgery in the era of Covid-19. British association of Day Surgery is at the forefront of achieving this.

This just leaves a couple of announcements to make. Firstly, Janet Mills who has been our exhibition Manger for 14 years retired earlier this year. She has worked tirelessly for BADS in managing and organising our exhibitors for our conferences. I am sure you will all join with BADS to wish Janet a long and happy retirement.

Thank you to all our exhibitors for the on-going support.

I would also like to thank the Talking Slides team on behave of BADS. They were the “Brains and brawn” behind what was such a successful conference. Their commitment and professionalism throughout the organising of the conference was incredible and we just could not have achieved such success without them.

A huge thank you to all our BADS members new and old for all your support. We look forward to seeing you at Nottingham in 2022, 16th and 17th June.

Fiona Belfield

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse3

Rachel Heard1 & Surrah Leifer2

1 Clinical Fellow in Anaesthetics, Royal Preston Hospital, Lancashire NHS FT

2 Consultant Anaesthetist at Royal Preston Hospital (Lancashire NHS Foundation Trust)

Corresponding author

Rachel Heard

Anaesthetic Department, Stepping Hill Hospital, Poplar Grove Street, Stockport SK2 7JE

Email: rheard@doctors.org.uk

Keywords: Paediatric; fasting times; post-operative nausea and vomiting; hypoglycaemia

Abstract

Background: Current hospital fasting guidelines for elective paediatric surgical patients are 6 hours for solids, 4 hours for breast milk and 2 hours for clear fluids as per Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) guidance. However newer evidence led to the Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (APAGBI) releasing a consensus statement in 2018 that 1 hour fasting for clear fluids is sufficient to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration. Many studies have found that paediatric patients are fasted for too long, leading to agitation and a higher risk of complications such as post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and hypoglycaemia.

Aim: To determine the average fasting time of elective paediatric patients.

Methods: Retrospective case note review of 100 patients.

Results: The mean fasting time was 12 hours 25 minutes for solids and 7hours 19minutes for clear fluids. 12 patients developed post-operative complications; 50% had PONV, one developed hypoglycaemia, and 5 were unrelated to fasting time (e.g., post-operative bleed).

Conclusion: Paediatric patients are being fasted for too long for both solids and clear fluids. All patients with PONV had prolonged fasting times. As only one patient had a blood sugar measurement, the true issue of hypoglycaemia is unknown. There is ongoing discussion regarding the benefit of intra-op blood sugar measurement. The recommended clear fluid fasting time for paediatric patients has been reduced to one hour. There needs to be improved communication between theatres and surgical admission teams to allow patients to have clear fluids following decision of the theatre list order. Information given to parents is being reviewed. Re-audit to determine if changes have been effective.

Introduction

Fasting guidelines for elective paediatric patients have classically been 6 hours for solid food, 4 hours for breast milk and 2 hours for clear liquid. Evidence suggested these times adequately reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration on induction of general anaesthesia. Newer research has since shown that fasting for 1 hour for clear fluids is sufficient to reduce the risk of pulmonary aspiration but also increases patient comfort [1].

However, in practice, many studies have found that the paediatric population is being fasted for excessively longer. Further evidence has demonstrated that excessive fasting can lead to complications including an increased incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting (PONV), detrimental effects to metabolism and increased patient agitation [1,2].

Therefore, an audit at Royal Preston Hospital was conducted to evaluate the fasting times for paediatric patients undergoing elective surgery and elicit any complications associated with prolonged fasting.

Method

The audit was a retrospective case note review of 100 elective paediatric patients presenting for surgery over a 3-month period (October –December) at Royal Preston Hospital. Information was collected from scanned pre-operative assessment notes and the theatre care pathway on Evolve (the hospital scanning storage system) and inserted into an Excel spreadsheet. The data was analysed manually. Data was collected on demographics, the planned surgical procedure, fasting times and any complications. The fasting times were calculated from the last time the patient had solid food/milk or clear liquid until they entered the anaesthetic room. This information is documented routinely as part of the nursing checklist on the patients’ theatre care pathway and anaesthetic review on day of admission. The theatre care pathway is then used for documentation of the patients’ surgical journey and could therefore be used to identify the time into the anaesthetic room and any complications that arose either prior to or at induction, intra or post-operatively.

Results

Included in the audit were 46 female patients and 54 male patients with a mean age of 7.5years, (range 0-17 years). The most common surgical specialties were Ears, Nose, Throat (ENT) 50%, Plastics 16% and Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 11%.

The mean fasting time for solid food was 12 hours and 25 minutes with a range of 4 hours 50 minutes to 19 hours 20 minutes. The mean fasting time for clear liquid was 7 hours 19 minutes with a range of 2 hours to 15 hours 45 minutes.

Six patients were cancelled but not due to inappropriate fasting times and there were no changes to the theatre list order due to fasting times. Two patients were identified as having complications on induction- one was due to loss of IV access and the other due to laryngospasm. 12 Patients had

documented post-operative complications: five PONV, one hypoglycaemia, four post-operative bleed, one rash and one laryngospasm. Information regarding fasting times given to parents at pre-operative assessment was verbal and documentation of this was often poor.

Discussion

The audit demonstrated that most paediatric elective patients were being excessively fasted with 58% of patients not having a drink of clear fluids for over 5 hours prior to surgery. Furthermore, over 30% of these patients were in hospital for over 3 hours prior to the start of their surgery. This suggests that if offered a drink of clear fluid on arrival to hospital, this would reduce the incidence of excessive fasting considerably.

One patient was fasted for only 4 hours and 50 minutes for solid food, they were 4 years old and there was no documentation regarding the reasoning behind not waiting for the full 6 hours. Although there were no documented complications, for an elective patient there should be clear documentation with regards to not waiting for the full recommended fasting time.

Documentation of fasting times was poor in 29% of cases with ‘last night’ being written as opposed to an actual time. For these results, the fasting time was calculated from midnight. It is likely to have been earlier in these patients and therefore the fasting times even longer than stated in the results.

The two patients who had complications on induction were felt to be unrelated to the excessive fasting times. Of the 12 patients who had documented post-operative complications, 50% were deemed to be unrelated to excessive fasting times (bleeding, rash, and laryngospasm).

5% of patients had documented PONV, the percentage of patients is likely to be higher as most studies have found an incidence of 13-42% [3]. However, of importance is that all five of the patients with documented PONV had been excessively fasted for both solid food and clear liquids. Although this does not show a causal relationship, none of the paediatric patients without excessive fasting times had documented PONV.

The one patient who developed hypoglycaemia was 10 months old and had breast milk 6 hours and 15 minutes prior to surgery and water 3 hours prior to surgery. The blood sugar was 3.9 and recovered quickly with dextrose. He was the only patient out of the 100 studied who had a blood sugar measured. Therefore, the true extent of hypoglycaemia in this population was unknown. He was not excessively fasted which could raise concerns for other young paediatric patients who could have undetected hypoglycaemia, particularly if they have been excessively fasted. This raises the question of the benefit of monitoring blood sugars intra-operatively for paediatric patients.

A criticism of this audit would be that it did not evaluate patient comfort. This would be difficult to assess as it was a retrospective analysis of patient records. On repeating the audit, a prospective method including patient satisfaction questionnaires could be considered.

A further criticism would be that the reason for excessive fasting times was not established, but it is likely to be multifactorial. The verbal information given to parents was often unclear in the notes, particularly for the patients who attended pre-operative assessment clinic. For those patients who

did have documented information, it was frequently from the surgical team who advised nil by mouth from midnight which would therefore lead to excessive fasting.

Six patients were cancelled but there were no cancellations or list changes due to inappropriate fasting times. Of the six patients who were cancelled, only one had clear documentation about being offered food and drink following cancellation.

Recommendations

- Due to the current evidence, the fasting guidelines at Royal Preston Hospital have been reduced to one hour for clear fluids for paediatrics.

- All paediatric patients should be given a drink of clear fluid on arrival to the pre-operative admissions lounge

- Improve communication between pre-operative admission lounge and theatres so that once list orders have been established, paediatric patients should continue to have clear fluids up until one hour before surgery

- Information given to parents needs to be reviewed- consideration of leaflets and posters in pre-operative clinics with the risks of excessive fasting included

- Audit results distributed to surgical specialties to ensure consistent information given to parents regarding fasting times

- Consideration of blood sugar monitoring intra-operatively

- Re-audit once paediatric elective work has been established post covid-19

References

- Mesbah A, Thomas M. Preoperative fasting in children. BJA Education 2017;17(10): 346–350.

- Thomas M, Morrison C, Newton R, Schindler E. Consensus statement on clear fluids fasting for elective pediatric general anesthesia. Pediatr Anesth. 2018;00:1–4

- Martin S, Baines D, Holtby H, Carr AS. Guidelines on the Prevention of Post-operative Vomiting in Children. The Association of Paediatric Anaesthetists of Great Britain & Ireland. 2016.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52846/313-pft.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse4

Dr Nyssa Comber

Dr Rebecca Binks

Dr Vishal Thanawala, Consultant Anaesthetist

Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust

Corresponding author: Dr Nyssa Comber. Email: nyssa.comber@nhs.net

Keywords: Peri-operative care; hemi-thyroidectomy; length of stay

Abstract

Introduction: Shorter post-operative stay leads to improved patient satisfaction and experience, as well as saving revenue and inpatient beds for the trust.

According to Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) data for Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH) from April 2017 to March 2018, the mean length of stay (LOS) after hemi-thyroidectomy was 1.75 days vs 1.21 days national average. If the national average were achieved at NUH, 41 bed days per year would be saved (£12,300).

The aim of the study was to identify reasons for prolonged length of stay in patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH, and target these as areas for improvement to reduce time spent in hospital.

Methods: Electronic records were used to collect retrospective data for patients operated across NUH from Jan 2018 to Dec 2019 (n=134). We calculated the overall mean LOS and analysed the reasons for delayed discharge in patients who stayed for 2-3 days post-operatively (n =46).

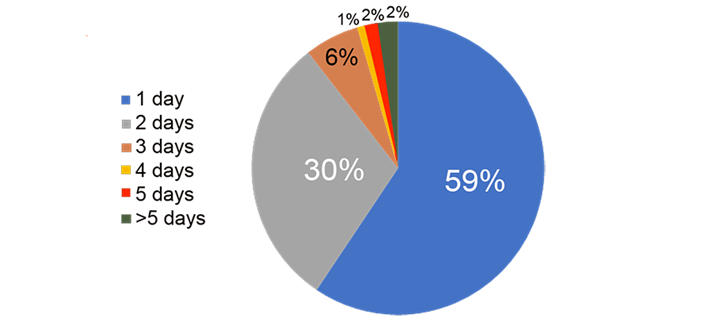

Results: The overall mean LOS was 1.72 days with median being 2 days. The breakdown for all hemi-thyroidectomies was as follows: LOS 1 day 59%, LOS 2 days 30%, LOS 3 days 6%, LOS > 3 days 5%.

No anaesthetic factors were identified as being contributory to extended length of inpatient stay and main reasons for delayed discharge were calcium monitoring and drain output.

Conclusions: Length of stay post hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH is longer than the national average with no anaesthetic reasons identified as being contributory. Calcium monitoring was appropriate as per British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons guidelines. There is no strong evidence in the literature for drain insertion post-hemi-thyroidectomy. There is potential to reduce the LOS of patients who were in the hospital for 2-3 days.

Liaise with surgeons to review the use of drains and formulate an ERAS pathway for management of patients undergoing thyroid surgery.

Introduction

Shorter inpatient stay is financially beneficial to trusts and preferred by patients, leading to increased patient satisfaction and better experience. According to Getting It Right First Time (GIRFT) data for Nottingham University Hospitals (NUH) from April 2017 to March 2018, the mean length of stay after hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH was 1.75 days vs 1.21 days national average(1). If the national average were achieved at NUH, 41 bed days per year would be saved, saving £12,300(1).

Day case targets are poorly adhered to nationally(2,3), and as such this is clearly an area that warrants improvement. The BADS Directory of procedures (6th Ed. 2019) provides benchmarking targets for the percentage of patients in whom zero night stays and one night stays are achievable. The directory states a zero-night stay target of 30% and a one-night stay target of 70%. The associated BADS National Dataset (2015) states a day case rate of 35% was being achieved in 5% of trusts and a day case rate of 3% was being achieved in 3% of trusts.

There are currently no trust guidelines for peri-operative management of hemi-thyroidectomy patients at NUH, resulting in variability of management which is often surgeon dependent. In theory, unless there are intra- or post-operative complications, hemi-thyroidectomy should not require inpatient stay >1 day. The aim of the project was to identify reasons for a more prolonged length of stay for patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH, and target these as areas for improvement. We were primarily looking to identify anaesthetic factors that had contributed to delayed discharge.

Methods

Electronic records were used to collect retrospective data for patients who underwent hemi-thyroidectomy (including completion thyroidectomy) between January 2018 and December 2019 (n=134). Anything documented by the parent team which in their opinion prevented discharge was noted. Reasons included: calcium monitoring, ongoing drain output, patient request, post-operative HDU admission, desaturation and new oxygen requirement, post-operative wound infection, abdominal pain, gynaecology review, urinary tract infection, pyrexia, lower respiratory tract infection.

The Early Warning Score (EWS) was also noted, both initially in recovery and at 12 hours post-operatively, to assess whether ‘scoring’ on the EWS was a factor in preventing discharge. The notes were reviewed to identify whether pain or post-operative nausea and vomiting were contributory to ongoing admission.

Inclusion criteria were: elective surgery, hemi-thyroidectomy or completion thyroidectomy, patient operated at NUH (both sites were included), and total hospital stay of 2 or 3 days. We only looked at those patients with a 2 or 3 day length of stay, as we predicted that those were the patients in whom we would be able to improve length of stay the most.

Exclusion criteria were: emergency surgery, any thyroid surgery that wasn’t hemi-thyroidectomy or completion thyroidectomy, patient operated at any other trust, and total inpatient stay of 0, 1, or >3 days.

Since this project was a sample survey aimed at making improvements locally, the only statistical analysis performed was to identify the mean/median length of stay, and mean/median EWS.

Results

There were 134 patients in the cohort overall before the 0, 1, and >3 day stays were excluded. 47 patients were identified as fulfilling all the inclusion criteria. 1 patient was excluded as no clear reason had been documented for delayed discharge. Therefore n=46.

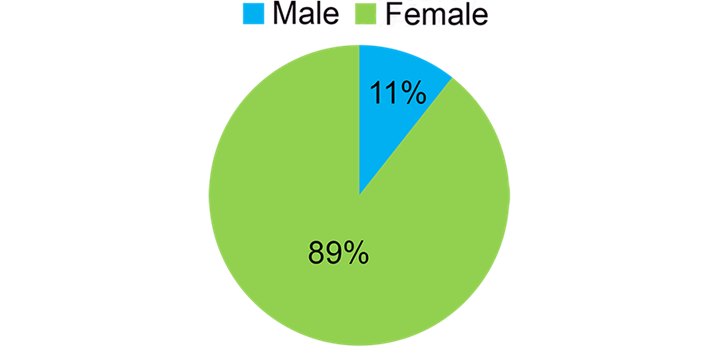

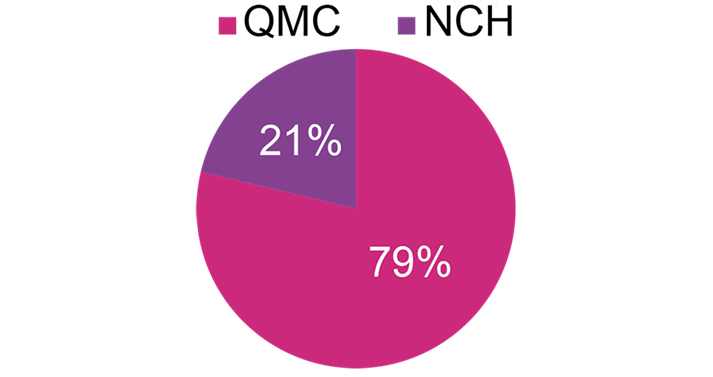

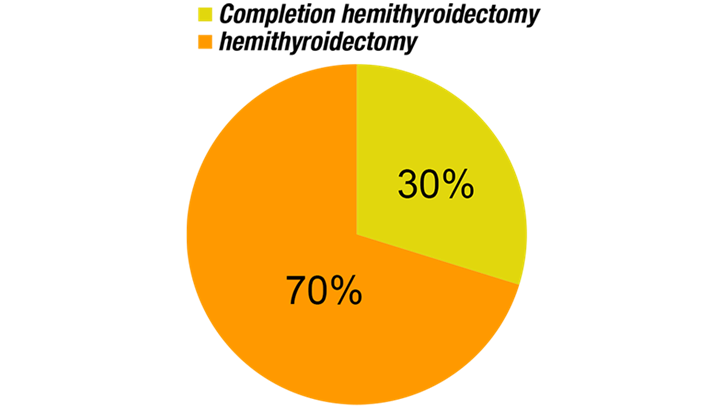

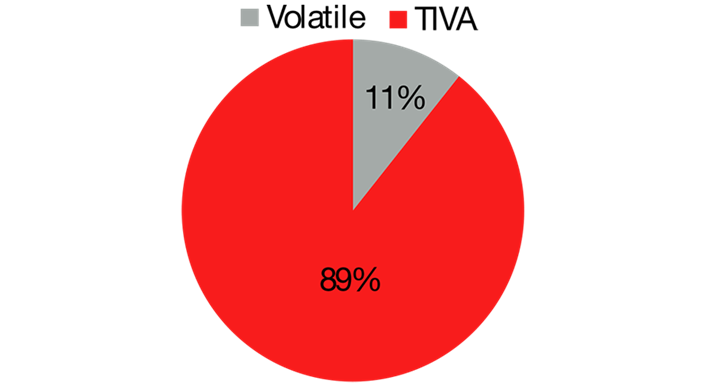

For the patients included, 11% were male, 89% were female [Figure 1: patient gender]. The mean age was 50.8 years. 21% of operations were performed at Nottingham City Hospital by endocrine general surgeons (apart from 1 case which was performed by thoracic surgeons). 79% of operations were performed at Queen’s Medical Centre by ENT surgeons [Figure 2: Hospital trust at which surgery was performed]. 70% of the operations were hemi-thyroidectomies, 30% were completion hemi-thyroidectomies [Figure 3: Surgery performed]. For 89% of cases the anaesthetic technique was TIVA; only 11% of cases were performed using volatile agents [Figure 4: anaesthetic technique].

Figure 1: Patient gender.

Figure 2: Hospital trust at which surgery was performed,

Queen’s Medical Centre (QMC) or Nottingham City Hospital (NCH).

Figure 3: Surgery performed.

Figure 4: Anaesthetic technique.

The length of stay for all hemi-thyroidectomies performed across NUH (n=134 i.e. whole cohort before exclusions) was as follows: LOS 1 day 59%, LOS 2 days 30%, LOS 3 days 6%, LOS 4 days 1%, LOS 5 days 2%, LOS >5 days 2% [Figure 5: Length of stay for all hemi-thyroidectomies at NUH for the period 1/1/18 – 31/12/19]. The mean LOS was 1.72 days, with median LOS 2 days.

Figure 5: Length of stay for all hemi-thyroidectomies at NUH for the period 1/1/18 – 31/12/19.

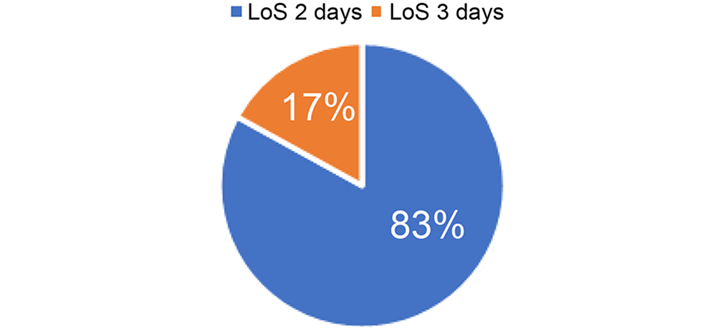

For those patients with LOS 2 or 3 days (n=46), 83% were inpatients for 2 days, 17% were inpatients for 3 days (all of whom were operated on at Queen’s Medical Centre) [Figure 6: length of stay 2 vs 3 days]. The mean LOS for these patients was 2.17 days, with median 2 days.

Figure 6: Length of stay 2 vs 3 days.

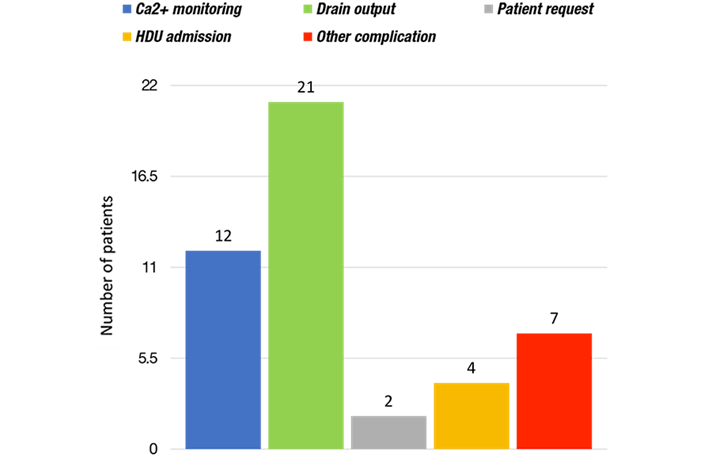

Reasons for delayed discharge were as follows: ongoing calcium monitoring required (26%), drain output too high for removal of drain (46%), patient request to stay in (4%), HDU admission required post-operatively (9%), other complication preventing discharge (15%) [Figure 7: Reasons for delayed discharge]. Other complications included desaturation and new oxygen requirement, post-operative wound infection, abdominal pain/gynaecology review, urinary tract infection, pyrexia, and lower respiratory tract infection.

Figure 7: Reasons for delayed discharge.

The mean Early Warning Score (EWS) in recovery was 0.76, with median 0. The mean EWS 12 hours post-operatively was 0.59, with median 0.

Intra- and post-operative analgesia was found to be appropriate and satisfactory, and there was no documentation of post-operative nausea and vomiting being a particular problem. No specific anaesthetic factors were found to have contributed to prolonged inpatient stay. The main reasons for delayed discharge were calcium monitoring and drain output.

Discussion

When reviewing all patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH from 1/1/18 – 31/12/19 (n=134), the length of stay is longer than the national average (1). The two most significant reasons identified during this project were calcium monitoring and drain output.

According to guidelines published by the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons (BAETS), calcium monitoring is not routinely indicated post-operatively for hemi-thyroidectomy, however it is indicated for completion hemi-thyroidectomy and total thyroidectomy(4). Within the scope of this project (n=46), all patients who were kept in for calcium monitoring had undergone completion hemi-thyroidectomy, and therefore this was appropriate as per BAETS recommendations.

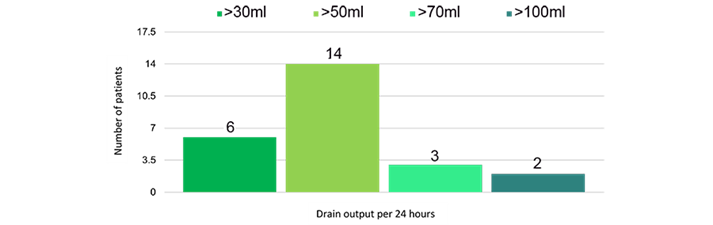

The theory behind drain insertion after thyroid surgery is to prevent haematoma formation, or accumulation of seroma (5). However, there is no strong evidence for this. Despite this, of the 46 patients included in this project, 25 had drains inserted (54%). There are no definitive guidelines at NUH about whether a drain should be used, or what volume of output is sufficiently low for the drain to be removed; as such, these decisions are often surgeon dependent. Generally, if the drain output was >30ml per 24 hours, the drain remained in situ and the patient stayed in hospital [Figure 8: Drain output per 24 hours].

Figure 8: Drain output per 24 hours for patients with inpatient stay of 2 or 3 days.

In one meta-analysis comparing drain vs no drain post thyroidectomy, there was no statistically significant difference between the two groups for haematoma, haemorrhage, hypoparathyroidism, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, or seroma(6). Drains have been linked to increased pain post-operatively; increased analgesic requirement, post-operative infection, and increased length of stay (5-8). Many studies have found no significant advantage of post-operative drain for thyroid surgery, including a Cochrane review, which found that there was no clear evidence that using drains in patients undergoing thyroid surgery significantly improves patient outcomes, but may be associated with increased length of hospital stay(8).

This project revealed that there were no zero-day stays in patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy for the time period studied i.e. no true day cases were performed. Whilst calcium monitoring was a relevant factor for delayed discharge in patients staying 2-3 days, this did not apply to patients staying 1 night who could have gone home on the day of surgery. Drain insertion prevented patients from going home on the day of surgery, however since this project was primarily investigating reasons for delayed discharge in patients staying for 2-3 days, the overall proportion of drains used for the entire cohort (n=134) was not specifically looked at and as such it was not noted how many of the 1 night stay patients had drains. Undoubtedly a significant factor in preventing zero-day stays is the fact that there is no day surgery pathway in place for patients undergoing hemi-thyroidectomy at NUH.

In view of the findings of this project, it would seem sensible to liaise with our surgical colleagues about the use of drains after thyroid surgery, and formulate an ERAS pathway for peri-operative management of patients undergoing thyroid surgery at NUH.

References

- Getting it right first time. Adult anaesthesia and perioperative medicine review. Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust. Provider level report. 6th February 2019.

- BADS Directory of Procedures (6th Edition, 2019).

- Skues, M. BADS Directory of Procedures: National Dataset Calendar Year 2015.

- British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons. Guidelines. Available at https://www.baets.org.uk/guidelines/ accessed 10/10/20.

- Kalemera Ssenyondo E, Fualal J, Jombwe J, Galukande M. To drain or not to drain after thyroid surgery: a randomized controlled trial at a tertiary Hospital in East Africa. Afr Health Sci. 2013;13(3):748-755. doi:10.4314/ahs.v13i3.33.

- Tian J, Li L, Liu P, Wang X. Comparison of drain versus no-drain thyroidectomy: a meta-analysis. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2017 Jan;274(1):567-577. doi: 10.1007/s00405-016-4213-0. Epub 2016 Jul 28. PMID: 27470116.

- Colak T, Akca T, Turkmenoglu O, et al. Drainage after total thyroidectomy or lobectomy for benign thyroidal disorders. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2008;9(4):319-323. doi:10.1631/jzus.B0720257.

- Samraj K, Gurusamy KS. Wound drains following thyroid surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007 Oct 17;(4):CD006099. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006099.pub2. PMID: 17943885.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52847/313-epcht.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse5

Apurva Jain1, Rosalind Broe1, Frances C Nolan1, Kim Russon2

1 University of Sheffield

2 The Rotherham NHS Foundation Trust.

Corresponding author Apurva Jain Email: ajain4@sheffield.ac.uk

Key Words: Covid-19; Day Surgery; Patient Experience

Abstract

Introduction: The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented levels of strain to the NHS, alongside anxieties amongst both staff and patients. As day surgery has been reintroduced, new NICE guidelines¹ have been instituted to ensure patient and staff safety, aspiring to alleviate some of these concerns. We wished to discover the impact on patient experience in day surgery.

Method: Between 10th-17th December 2020, all patients who had attended the DSU at Rotherham Hospital were telephoned post-operatively to complete a brief questionnaire regarding COVID-19 safety measures for their surgery. Patients were asked if they had self-isolated prior to surgery and if social distancing was maintained during their time at the DSU. All patients gave consent for their responses to be included in this audit.

Results: We collected data from 73 patients. 97% of patients were asked to isolate for a minimum of 3 days prior to their surgery. 3% reported not being asked to isolate at all. 88% of patients were given some form of information regarding what isolation entailed, from various hospital sources. 99% of patients felt appropriately social distanced during their day surgery stay.

Conclusions: Overall, most patients felt adequately socially distanced in our DSU and appropriately informed about isolation. Investigation into why all patients do not receive the Trust guidance on isolation is required.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought unprecedented levels of strain to the National Health Service (NHS) 1, 2, alongside anxieties amongst both staff and patients3. With the reintroduction of day surgery, both National Institute for Health Care and Excellence (NICE)4 and the Public Health England 5 created guidelines to advise on the safety measures that hospitals should put in place. This aimed to ensure patient and staff safety, and to alleviate the concerns felt by these groups.

The NICE Guideline4 published in July 2020 regarding planned care recommends that for all planned procedures needing anaesthesia (general, regional and local) or sedation

Patients should be advised to: follow comprehensive social-distancing and hand-hygiene measures for 14 days before admission, to have a test for SARS-CoV-2 no more than 3 days before admission ensuring the results are available beforehand, and to self-isolate from the day of the test until admission.

This then fulfils low-risk criteria according to Public Health England (PHE) guidelines updated in June 20215, thus allowing the patient to follow a low risk covid pathway during their hospital admission. This involves 2m social distancing (or appropriate physical barriers e.g., curtains or screens) and wearing airborne personal protection equipment (PPE) including a face mask. All staff and other care workers must maintain social/physical distancing of 2 metres where possible (unless providing clinical or personal care and wearing PPE as per care pathway). Staff should wear a surgical fluid resistant mask (FRSM), gloves, apron and eye protection. In addition, both sets of guidance4, 5 recommend that visitors are kept to a minimum.

The Rotherham Foundation Trust (TRFT) has introduced guidance based on national guidance 4, 5. Initially, patients were a minimum of 2m distance apart. However, screens and plastic curtains have since been installed (Figure 1), allowing for greater utilisation of space within the Day Surgery Unit (DSU).

Figure 1: Photographs of the safety measures implemented at Rotherham General Hospital.

Patient numbers have been kept low to ensure appropriate social distancing and hygiene measures can be maintained. Initially patients were kept distanced by either waiting within an individual consulting room or at a DSU bedspace until it was time to go to theatre. Now they are able to sit in the waiting area separated by clear Perspex screens which have been agreed by infection control. Staff remained 2m distanced from patients but follow all hygiene and PPE measures when care within 1m is required, wearing an apron, FRSM, eye protection and gloves. There are currently no visitors permitted to the DSU routinely and patients are instead helped to and from their transport outside of the unit.

Prior to attending the DSU, all patients are given an appointment for a drive through COVID-19 test 72 hours before surgery and are told to self-isolate from the time of their covid 19 swab. Prior to the covid-19 pandemic, patients were all contacted the day before surgery to check no changes to their health sine their pre-assessment and to confirm attendance and remind them of their starvation guidance. They are now also asked about symptoms of COVID-19.

The aim of the service evaluation carried out is to explore if the measures described above had been implemented for all patients and ask if it patients felt safe.

Methods

Following approval from TRFT clinical effectiveness department, all patients who had day surgery through DSU at TRFT between 10th-17th December 2020 were telephoned post-operatively to complete a brief questionnaire regarding COVID-19 safety measures.

Patients were asked if they had self-isolated prior to surgery and what guidance, if any, they had received from TRFT in regards to self-isolation. Patients were also asked if social distancing was maintained during their time at the DSU and if they felt these social distancing were appropriate.

Approval was obtained from the Trust to perform the patient questionnaire. In addition, patients gave verbal consent to utilise their responses anonymously, as part of the service evaluation.

Results

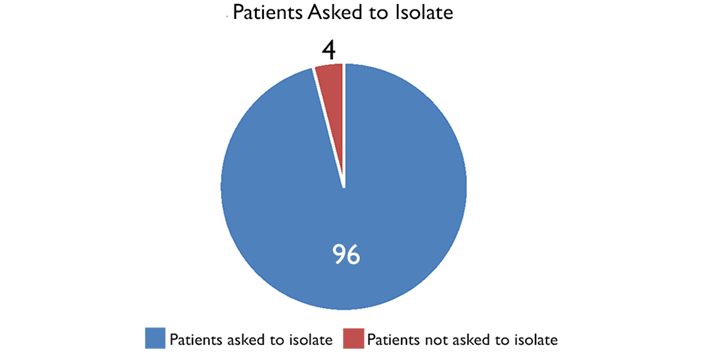

73 patients answered the telephone when we called. With regards to isolation, 70 patients (96%) were asked to isolate for a minimum of 3 days prior to their surgery (Figure 2). The other 3 patients (4%) reported not being asked to at all (Figure 2).

Figure 2: A pie chart showing the % patients asked to self-isolate for at least

3 days prior to their surgery.

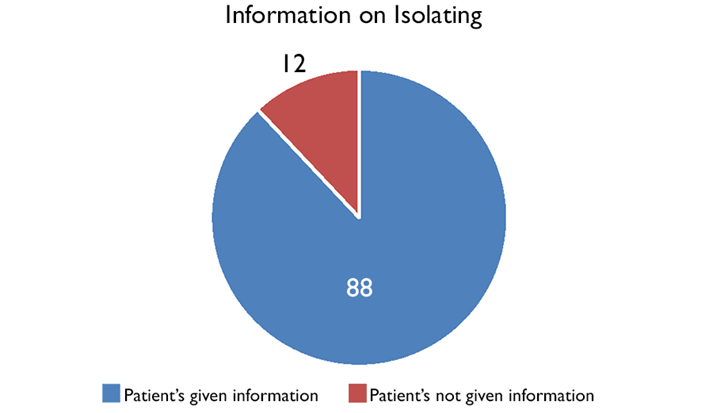

64 patients (88%) reported receiving information of what isolation entailed (Figure 3). However, this information came from a variety of sources including the Day Surgery Unit receptionists, assessment nurses and booking administration staff. The surgical division circulated information around isolation to these different departments, but we cannot be sure how standardised the information given by different people was.

Figure 3: A pie chart showing the % patients given some information about

what self-isolation entailed, either in writing or verbally.

Furthermore, it did not sound like this information was standardised and came from a variety of sources, including the Day Surgery Unit receptionists, assessment nurses and booking administration staff.

All but one of the patients contacted (99%) reported that 2m social distance was maintained throughout their stay at the DSU and felt this was appropriate.

Discussion

The results of this service evaluation are encouraging with regards to the implementation of COVID-19 safety measures at The Rotherham Foundation Trust (TRFT) Day Surgery Unit (DSU). During the period in which this service evaluation took place, the Trust managed a 97% success rate with regards to informing patients of the NICE4 recommendation of 3 days patient isolation pre-operatively. However, this service evaluation assessed only whether patients had been asked to isolate and not whether they had actually isolated. Whether patients followed the advice given or not would be more difficult to assess and would rely on patients reporting honestly if they had failed to do so. To be admitted for surgery the patients needed to say that they had isolated.

Another area of success identified by this service evaluation was the use of 2m social distancing within the DSU. Only one of the 73 patients contacted did not feel this had been achieved during their time at the unit, describing how a member of the domestic services team had been cleaning in the unit without wearing a mask of maintaining a distance from others. As this was only reported by one patient, it may have been an isolated issue and the incidence was reported to senior day surgery staff. This has been reported to the DSU manager to investigate. A repeat service evaluation with a larger sample size is needed to ascertain if similar incidents have been occurring and if further staff training on the use of PPE and social distancing is required.

This service evaluation has identified that improvements to how and when patients are given information about what self-isolating entails are required. Despite the majority of patients being asked to isolate pre-operatively, only 88% reported being given information on what this involved. In order to ensure patients self-isolate effectively, information should be given on what they can and cannot do during self-isolation, and what support is available to them during this time. There is a Trust agreed document based on the national guidance. This has been re-circulated to schedulers and made available on the Trust’s intranet. This information is now also available on the Trust intranet and website.

Currently, patients report information on self-isolation being provided by a variety of staff members at varying times. A lack of clarity and repetition when providing this information may explain why some patients did not feel they received accurate explanations of what is required during self-isolation. This information is usually given by schedulers prior to pre-operative assessment to ensure that patients are taking the correct number of isolation days, using the correct method as stated in the Rotherham NHS foundation trust guidance. If there are new staff to these teams it is important that to ensure that these staff are aware of their responsibilities to provide this information.

In conclusion, this service evaluation has already resulted in some changes but there still may be room for some improvement while we need to continue with measures to reduce the risk of transmission of covid 19. The Rotherham Foundation Trust has been successful in providing a safe elective surgery service through the Day Surgery Unit since June 2020 despite a further wave of covid19. The implementation of current national guidance for maintaining patient safety during the COVID-19 pandemic has patients feeling safe during their admission. The impact of covid-19 is still changing all the time and with it the guidance. It is therefore important to review and up-date the guidance as necessary and consider repeating this service evaluation.

References

- Wielogórska N, Ekwobi C. COVID-19: What are the challenges for NHS surgery?. Current Problems in Surgery. 2020; 57(9): 100856.

- Iqbal M, Chaudhuri A. COVID-19: Results of a national survey of United Kingdom healthcare professionals’ perceptions of current management strategy – A cross-sectional questionnaire study. International Journal of Surgery. 2020; 79(1):156-161.

- Jeyabaladevan P. COVID-19: an FY1 on the frontline. Medical Education Online. 2020; 25(1):1759869.

- National Institute of Clinical Excellence. COVID-19 rapid guideline: arranging planned care in hospitals and diagnostic services. Published 27th July 2020. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/NG179 [Accessed 23rd January 2021].

- Public Health England. COVID-19: Guidance for maintaining services within health and care settings Infection prevention and control recommendations. Version 1.2 published 1st June 2021. Available from:

https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/990923/20210602_Infection_Prevention_and_Control_Guidance_for_maintaining_services_with_H_and_C_settings__1_.pdf [Accessed 5th June 2021].

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52854/313-do-patients-having-day-surgery.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse6

Click on the image to be taken to the HCUK page about the conference.

Download the pdf from the link at the bottom of the page.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52755/breast-day-surgery-sept-2021.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse7

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse9

Louise Caney

Louise Caney discusses the impact of COVID-19 on surgical waiting lists and highlights some key strategies to support recovery for operating theatres. She offers an insight into how digital operating theatre systems can assist with managing the backlog and finding additional capacity.

There are many facets to managing a surgical waiting list. A multi-disciplinary, co-ordinated approach – involving clinical, administrative, organisational, and technological resources – is needed to ensure patients on the waiting list are scheduled for surgery as efficiently and safely as possible. Under normal circumstances, operating theatres are busy, complex places, experiencing challenges every day, while managing elective and emergency cases. The goal has always been to ensure patients receive the surgical interventions they require within an acceptable time frame while maximising the productivity of operating theatres. Everything changed at the beginning of 2020. Operating theatre activity was severely disrupted as the Coronavirus pandemic became the biggest challenge the NHS has faced since in a century. The BMJ stated last year, “The number of people who had been on waiting lists for more than 18 weeks in July [2020] was the highest since records began in 2007... Just 46.8% of patients were treated within 18 weeks in July [2020], against the 92% target – the lowest since records began.” (September 2020).

The importance of increasing pace and working more efficiently and smarter is now an immediate priority as planned surgery resumes and, with the Government spending £160 million to tackle the waiting list backlog, a period of recovery has begun. However, extra funding is only part of the solution.

Professor Tim Briggs, chair of the Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) national programme, highlighted some hard-hitting statistics and raised some important points during the Effective Operating Theatres Summit on 9 June 2021. Currently 5 million people are waiting for elective surgery in England compared to 3.7 million in 2003/4. The GIRFT national programme improves treatment and care of patients by using data to drive evidence-based treatments, benchmarking, and a review of services to drive change.

In November 2018, 2,432 people had been on the waiting list for more than 12 months. With an increasing population and increasingly an ageing population, the impact on NHS surgical teams and operating theatre has never before been more intense. During the Effective Operating Theatres Summit (which took place online), several strategies were identified that need to be considered and implemented to manage this situation. Theatre productivity and efficiency, along with the patient experience, were front and centre of the virtual summit. Discussions included the considerations and strategies needed to manage the impact caused by the pandemic on surgical services. Some of

these are already in place – in particular, the creation of surgical hubs, pooled surgical lists, utilisation of the private sector and the move towards more day surgery.

The GIRFT programme’s key messages regarding the management of the challenge we face focused on shared decision making, increasing capacity and productivity, and reducing patient length of stay and unnecessary surgery. Ring fencing operating theatre services by creating specialist theatre hubs, so waiting list surgery can continue during the pandemic, has already been deployed across the country. The Royal College of Surgeons has called for the creation of specialist hubs focused on just routine surgery – hip and knee replacements and cancer surgery, for example. In May 2020, a specialist cancer hub was created by the Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust and, in just the month of May, operated on 761 patients from the 10 Trusts across London, with this number increasing.

Meeting the challenge to balance the need for cancer surgery against the risk to individuals of coronavirus was highlighted by Vin Diwakar NHS medical director for London, back in 2020. MacMillan, the cancer charity, has supported the need for ring fencing cancer services, including surgery, to prevent a delay in treating patients with cancer (November 2020).

Pooled waiting lists are another way of managing the waiting list situation by increasing capacity and efficiency by placing some patients onto the shortest waiting list of a surgeon who may not necessarily be the patient’s original surgeon. A patient needs to be a suitable candidate for a pooled list but there are benefits if the right balance is struck between some patients being added to their surgeon’s waiting list and others to another surgeon’s list.

Day surgery is a well-established approach to managing surgery, but now more than ever it needs to be considered for a wider range of surgical interventions.

Managing surgical cases as a day case leaves inpatient beds for those who cannot be managed as a day case and prevents prolonged length of stay, a risk for elderly patients in particular.

The daily ‘hot’ surgical clinics described by the GIRFT programme is an approach that enables patients on an ambulatory emergency pathway to be reviewed by senior clinical decision makers, access diagnostic services and be booked onto a hot list while in the surgical assessment unit, returning for surgery at a specific time. Utilising the private hospital sector has also reduced the burden on acute NHS hospitals waiting lists, a strategy used by several Trisoft customers.

Capturing activity in these private hospitals was managed easily by configuring the digital theatre system to add these new locations, so theatre activity could be captured.

To understand why elective and, in some circumstances, urgent cases have been so severely impacted during the pandemic, we need to look at some of the leading factors: reduced capacity, reduced efficiency and productivity, and unavailability of healthcare professionals. As the number of hospital admissions of patients with coronavirus overwhelmed wards and critical care beds, it was necessary, in some cases, to use operating theatres to care for critically ill patients. Certainly, theatre capacity for emergency cases and obstetric surgery was preserved but patients waiting for non-urgent, elective surgery were placed on the waiting list with, in some cases, no date for their surgery in sight.

It is worth mentioning how the impact on the pandemic affected healthcare teams and the impact this had on surgical activity. Healthcare workers themselves became infected with the virus or had to self-isolate if exposed to the virus, having a devastating effect on hospital services. Patients needed to be tested prior to admission and, if positive, surgery was cancelled and theatre lists re-ordered. The delays caused by testing, although clearly essential, added another layer of complexity to a patient’s route to surgery. A year on since the start of the pandemic, the processes needed to ensure patients and staff are tested, have arguably become streamlined and routine, which was not necessarily the case 12 months ago.

Protecting staff and patients by minimising the volume of outpatients moving through and congregating in a hospital setting has been essential since the beginning of the pandemic.

The strict social distancing rules has meant the way patients interact with their care providers needed to change quickly. Telehealth and online consultations have become the norm and may well continue once we return to non-pandemic conditions.

There has also been an increasing trend towards patient self-assessments being completed using digital platforms or portals. This started years before the pandemic as a way of improving efficiency and reducing the need for patients coming to hospital. However, a face-to-face consultation, particularly with an anaesthetist, will in many cases be necessary.

Digital operating theatre systems It is important to give a shout out to the contribution technology and, in particular, the digital operating theatre system has made and continues to make under normal conditions, but certainly during and after the pandemic, as surgical services return to normal – assisting with the ‘heavy lifting’ needed to manage capacity, scheduling, theatre pathways and pre-operative assessments.

With the pressure to manage the waiting list backlogs now on, key to moving patients safely and efficiently from the waiting list to an appropriate session is a streamlined interface with an organisation’s patient administration system (PAS) waiting list. Details of each patient including priority should be included in the waiting list so a scheduler can understand who needs to be added to a list and when.

Clinically, having a more detailed understanding of the patient’s situation is vital. Their condition needs to be shared and available, if not via the waiting list interface, then via other clinical noting, accessible to the surgical team.

With an increase in pace and a rapid roll out of new ways of working, the benefits of a digital theatre system cannot be ignored. The complexities around theatre session management include being able to create session plans easily and then changing, deleting or adding ad hoc single sessions. Placing a session no longer required on offer to other teams, splitting sessions, making changes to an existing session, adding resources, or requesting that a session be locked by a consultant, are all easily achievable using a digital theatre system. It may also be necessary to cancel or postpone a patient at short notice and re-order a list.

A top priority already mentioned is ensuring operating theatres and operating theatre personnel are deployed effectively, utilising the available theatre space as much as possible, so as many patients as possible receive their surgery. Being able to see what is available and where within an organisation’s operating theatre department is ideally achieved digitally and in a format that gives a bird’s eye view of theatre capacity in a centralised way, up to six weeks in advance. This means partially optimised theatres are not left that way.

How operating theatre services recover will depend on many factors. We cannot yet return to normal but, as of 2 June, we are in a very different place with a significant reduction in hospital admissions thanks largely to the successful vaccination programme. Despite the calamitous situation of the last 15 months, surgical services have, wherever possible, found a way to manage the waiting list backlog, putting the patient at the forefront of surgical operations and that is important.

Preserving staff morale and wellbeing continues to be an essential part of the recovery process, while ensuring the patient experience is the best it can be. Many lessons have been learnt and the different way of managing surgical services may well continue for many years.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/52855/managing-waiting-lists-in-the-covid-19-era.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods?id=2231#collapse10

Dr. Mary Stocker

There is a need for day surgery to become the default pathway, wherever possible, but the message must be communicated early on and there needs to be a better understanding of which types of procedures can be performed. The British Association of Day Surgery argues that hospitals need to adopt an ‘inclusion’ rather than an ‘exclusion’ philosophy.

The British Association of Day Surgery recently hosted a series of virtual conferences highlighting the need to move to day case surgery as the ‘default’ position, wherever possible. As NHS Trusts battle with a backlog of elective surgery, in the wake of the pandemic, day case pathways will be key to NHS recovery. However, avoiding hospital stays and sending patients home on the same day offers other important benefits – both in terms of patient satisfaction, reducing the risk of healthcare-associated infections, and improving outcomes. Dr. Mary Stocker, past president of BADS, and consultant anaesthetist and recent director of Torbay’s Day Surgery Unit, addressed some of the misconceptions with regards to ‘what constitutes day case surgery’, providing an insight into which patients are eligible, the types of procedures that can be performed, and the key considerations to ensure successful outcomes.

Speaking at Day Case Major Knee Surgery: ACL reconstructions to Total Knee replacements, she commented: “Initially day case surgery was ‘a planned procedure’, but it isn’t just about elective surgery anymore,” she commented. “We are trying to push more and more urgent surgery into the day case arena.”1

She pointed out that day case surgery must be the ‘intention’ in order to meet the definition: “If a procedure is not planned as a day case, it does not count as a day case,” she explained, adding that the term “23-hour stay” does not refer to day surgery. To be a day case the patient must be admitted, operated upon and discharged on same calendar day.

Dr. Stocker emphasised that it is important that booking, pre-op assessment, admission, surgery and discharge are managed by a dedicated day surgery team, in order to achieve high quality outcomes. She outlined the pathway as follows:

- GP referral for procedure

- Surgical outpatient appointment

- Patient Selection l Booking

- Pre op assessment

- Admission

- Surgery l Discharge

- Recovery at home

Dr. Stocker went on to highlight the BADS directory of procedures which lists over 200 procedures that can now be performed as day case surgeries.2 However, she raised the question: ‘how much awareness is there at the start of the pathway of the types of procedures that can be performed?’ She pointed out that raising awareness among GPs is vital to ensure that primary care colleagues know which procedures can be considered for day case surgery and that they communicate the ‘day surgery message’ early on to patients.

“GPs need to know that hip replacement, knee surgery and hysterectomies can be performed as day cases, otherwise the GP might tell the patient they are referring them for surgery and they are likely to be in hospital for three days. The patient will then have this expectation and, once they have this in their mind, this is what is likely to happen,” said Dr. Stocker. Effective communication with primary care colleagues is therefore required to ensure GPs know which patients are appropriate and that they ensure the patient is ‘fit to be referred’ – including diabetes management, for example.

She pointed out that the situation is very similar with surgical outpatient clinics. “We need to ensure all of our surgical colleagues are singing from the same hymn sheet. They need to know which procedures are suitable; which patients are appropriate; and they need to recognise when a patient may require optimisation before listing. They also need to reinforce the day surgery message,” she explained.

“We want the surgeon to confirm day case management intention and default suitable procedures to day case surgery. It is also important to remember, that if a patient is not fit for day surgery, they are probably not fit for elective surgery. Patients need to be optimised to get them as fit as they can possibly be, to ensure they are considered appropriate,” Dr. Stocker continued.

In 2001, the Audit Commission’s ‘Basket of Procedures’ listed 25 procedures that could be performed as day case surgery, but Dr. Stocker pointed out that a great deal has changed since then; today, the following surgical criteria need to be considered:

- Can the patient be reasonably expected to manage oral nutrition post-operatively?

- Can the pain of the procedure be managed by simple oral analgesia supplemented by regional anaesthetic techniques?

- Is there a low risk of significant immediate post-operative complications (eg catastrophic bleeding)?

- Is the patient expected to mobilise with aid post-operatively?

She advised that surgical teams should evaluate existing inpatient procedures with a short length of stay, then consider: what would we need to change in the pathway to enable them to become a day case? “Traditionally, we were told that procedures lasting longer than 60 minutes shouldn’t be undertaken as a day case, but this has changed,” she commented, highlighting findings by Skues (2011)3, which showed no statistical difference in unplanned admissions following day-case procedures lasting less than 60 minutes, compared to procedures lasting greater than 60 minutes.

Dr. Stocker added that the US has been ahead of the UK for some time – procedures lasting 3-4 hours are now routinely performed on an ambulatory basis.4

She pointed out that nearly ALL surgery should be day or very short stay, and this now includes fairly complex surgery, such as:

- laparoscopic nephrectomy

- prostatectomy

- laparoscopic hysterectomy

- vaginal hysterectomy

- thyroidectomy

- mastectomy

- shoulder surgery

- anterior cruciate ligament

- lumbar discectomy

- abdominoplasty

With the publication of the Sixth Edition of the BADS Directory of Procedures2, the list has been extended even further to include more complex surgery such as: l Craniotomy l Caesarean Section l Joint Replacements l Carotid Endarterectomy l Endovascular Aneurysm Repairs l Emergency Procedures She pointed out that day surgery has come a long way since the early 90s – within gynaecology, day case units have moved from performing hysteroscopies to undertaking hysterectomies; within orthopaedics, they have moved from arthroscopy to uni-chondylar knee replacements/total hip replacements; and, in head and neck surgery, they have moved from tonsillectomy to thyroidectomy. When deciding which patients are eligible, surgical teams need to consider: are the patient’s risks increased in any way by treatment on a day stay basis and would management be different if he/she were admitted as an inpatient? If the answer is ‘no’, the patient is probably suitable for day surgery.

Other considerations include social factors. What about patients who live alone? Are all procedures equal and does everyone require a carer? In the past, patients who lived alone had to be treated as inpatients, but this is now changing.

The Torbay Model provides carers into patients’ homes if they live alone, while the Norwich Model allows some patients home without carers after certain procedures, but they must have someone to safely escort them home. Both pathways have now been in place for a number of years, have resulted in excellent patient satisfaction and no adverse outcomes, and are endorsed by BADS and the Royal College of Anaesthetists.5

Dr. Stocker pointed out that distance from hospital is rarely a problem even in rural areas. It is important to remember that the patient only needs to be one hour from a hospital that can treat the condition, not necessarily the operating hospital. She added that the vast majority of patients are socially appropriate for day surgery or can be enabled to be so with proactive management. She went on to discuss the medical factors that require consideration. However, in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Royal College of Surgeons of England’s selection criteria included an age limit of 65- 70 years, ASA I & II, BMI<30 and stipulated that the maximum operating time should be 60 minutes. In 2002, the Department of Health announced that “patients should only be excluded from day surgery if a full pre-operative assessment shows a contraindication.”