David Bunting

David Bunting

Having taken up the position of JODS Editor in January, it is with great pleasure that I introduce the first edition of JODS in 2018.

The NHS has been put under intense strain recently as a result of winter pressures with day-surgery units being used for inpatients and many operations cancelled. Financial austerity has led to Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) taking matters into their own hands and introducing minimum waiting times and NHS England has removed penalties for patients waiting over 52 weeks for treatment. The inevitable increase in waiting times means that it has never been more critical to recognise the importance of well-managed, dedicated day-surgery units in mitigating these problems by efficiently treating the 75% surgical patients treated as day-cases in the UK.

BADS is committed to delivering a high quality Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM) and undertook a membership survey to find what our members value most in the yearly conference. See the full results published in this edition of JODS. I am pleased to be able to report that as a result of feedback, we are continuing to host a two-day meeting, with no increase in the conference fee and a networking dinner included in the price for this year’s meeting in Sheffield. Preparations for the meeting are well under way and please be reminded that abstract submission and registration are open via the BADS website. Please book your study leave now if you haven’t done so already and I look forward to receiving your abstract submissions prior to the deadline on Friday 6th April. After many years holding meetings outside the capital, I am very excited to be able to announce that the 2019 ASM will be held in London. This will be well-timed to commemorate the association’s 30th annual meeting and promises to deliver a full programme of expert speakers as well as a chance to network during the evening social event.

This edition’s scientific papers include an audit of patients with a history of chronic pain being managed successfully through a day surgery pathway; a review on overcoming the problem of patients who do not have an overnight carer, a report on outcomes and satisfaction with semi-elective day case hand trauma surgery and a randomised controlled trial studying the efficacy and recovery profile of low doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine for spinal anaesthesia.

The journal has gone through significant change in recent months, having moved over from a printed journal to web-based and app-based formats. Many readers are now accessing their journal subscriptions through these platforms and it was felt that the time had come for JODS to embrace the available technology. The Editorial team is always trying to improve the service it provides to BADS members and JODS readers and we are currently working on making published articles available to download directly in PDF format.

Finally, I would like to thank Tim Rowlands as past-Editor for his hard work over the past three years. He has endeavoured to maintain the high standard of articles published in the journal, whilst keeping the subject content topical and relevant to day-case surgery. He has also efficiently steered the journal through recent changes and importantly this has all been achieved without charging authors an article processing fee, putting JODS in a decreasing minority of journals that are able to publish without charge to individual authors. I hope you enjoy this edition of JODS. As always, feedback on the content and letters to the Editor are gratefully received.

David Bunting

Editor

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6181/281-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse0

Mary Stocker

Mary Stocker

I write this in the hope that as the snow thaws across Dartmoor and the South West is once again connected to the rest of the country the severe pressures experienced across the NHS this winter might also begin to subside. I am sure that like us your trust has been on the highest levels of alert on many occasions already this year. It is at times like that that the value of having efficient and effective day surgery services are truly appreciated, whilst the rest of the NHS is struggling to cope with the enormous pressures, our day surgery units continue to do what we do best day in and day out, that is, deliver high quality care to an increasing number of patients on the day scheduled without delays and cancellations. In order to do this it is imperative that our day surgery units are not used for “escalation purposes” and we have recently heard at our national meetings a number of examples where this has been allowed to happen resulting in decimation of the day surgery process and staff demoralisation. I was pleased to hear earlier in the year that National Emergency Pressures Panel were recommending that in times of increased demand day case procedures should be ramped up to take pressures off in-patient beds. However, of some concern was their statement that day-case facilities could be used flexibly to provide inpatient care to help with the expected surge. I am this week delighted to report that after conversation with this team it appears that that was a misunderstanding and there is complete appreciation of the need to protect our precious day surgery facilities at times of escalation. I am delighted to report that BADS will hopefully be contributing to future discussions so hopefully our message will continue to be supported.

Council have been working hard on a variety of projects over the last few months. Of note our work with the NHS Improvement Model Hospital Project is paying huge dividends. We hope that they will shortly be launching their day surgery compartment which will enable trusts to benchmark their performance against all the procedures within the BADS Directory. There will also be the ability to identify the top performers in terms of day surgery rates for each of the individual procedures which will give us the opportunity to learn from our best performing colleagues.

Each year we learn of teams who are introducing more complex procedures into the day surgery arena, last year it was the neurosurgical teams from Southampton who told us about their pioneering work introducing day surgery craniotomies. This year’s focus is day surgery arthroplasty with teams from Northumberland and Hull leading the way. The team from Hull will be presenting their work in June at our ASM and in September we are running a “joint” conference in association with Health Care Conferences where teams from Northumberland, Hull and Torbay will be showing us how to transform our arthroplasty service into one which embraces day surgery.

At this time of year, we start looking towards the future and in particular considering recruitment to our council. We anticipate having three places on council this year and would be delighted to welcome applications from any current BADS members who would like to become more involved in the organisation of our Association. We will be sending out a message shortly inviting you to apply for a position on council so now is the time to start thinking about it. More information can be found under the news section of the website.

Finally we are endeavouring to update our directory of day surgery units with the correct contact details of medical and nursing leads for all the units across the UK. I am sure you appreciate this is a difficult task. If each member (ie you!) were able to contact Nicola at bads@bads.co.uk with the name of the medical and nursing lead for day surgery in your own trust and one or two adjacent trusts we could have 60% of the information we need in a very short time. Do it now – this week, if you put it off it will never happen!

Thank you again for the support you give to BADS and we look forward to seeing many of you in Sheffield in June.

Mary Stocker

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6191/281-pres.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse1

The British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) Council is committed to delivering high quality Annual Scientific Meetings (ASMs) and conferences for our members and anyone interested in day-case and short-stay surgery. We have noticed a fall in attendance at our ASM over the past few years and wished to explore this by conducting a survey of BADS members. Thank you to all those members who completed the survey.

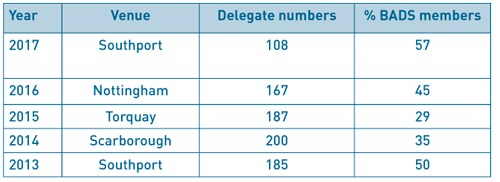

Table 1 ASM attendance numbers

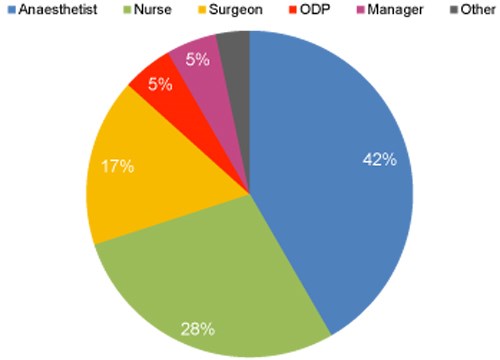

Only 30% of respondents had attended the BADS ASM 2017 in Southport. Of those that attended, 79% attended the networking dinner held on the Thursday night. The dinner is included in the 2-day delegate rate.At the time of this survey (November 2017), BADS had 297 members. We have not always collected data on the profession of our membership but have started to in March 2016. 110 BADS members completed this survey (37%). 42% were anaesthetists, 28% nurses, 17% surgeons, 5% ODPs, 5% managers and 3% “other”, which included 2 ward managers, an administrator and a physician’s assistant in anaesthesia.

We are well aware of the pressures across the UK on hospitals to release staff to attend courses and conferences, the reduction of study budgets for doctors and the absence of study budgets for allied health professionals despite the recent introduction of revalidation for nursing staff and the requirement for continuing professional development. We wanted to find out if these were the reasons for not attending or was it a problem with the venue location or programme.

Figure 1. BADS members responding to survey by professional group.

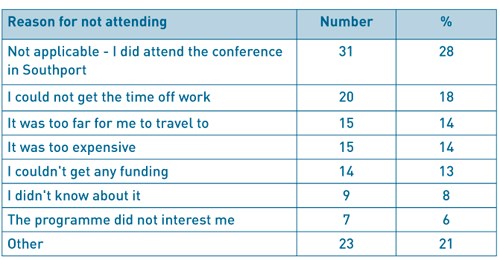

Table 2 Reasons for not attending

BADS ASM has always been a two-day conference to allow for the networking dinner to be included. We were pleased to hear that 45% of respondents would like it to stay as 2-day conference and 24% did not mind with 24% saying they would prefer a 1-day conference.Other reasons given for not being able to attend the BADS ASM in 2017 were other commitments (10%) and not practical to attend every year (3%).

With cost in mind, we asked for opinion on the conference fee. 63% of respondents thought the cost was about right and 36% thought it was too much. 1 respondent thought it was cheap. One way to reduce the cost of running a conference is to reduce the amount of printed material provided on the day. This would also be more environmentally friendly. 30% of respondents didn’t mind, 27% of respondents would prefer an all-electronic programme and only 8% preferred an all paper programme.

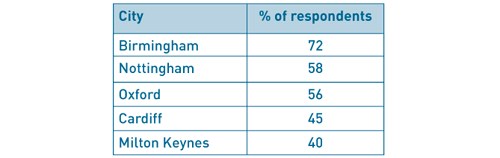

We like to plan our conference venue 2-3 years in advance and wished to explore where our BADS membership would consider attending. Understandably more central locations were favoured, we assume due to easier travel arrangements.

Table 3 Cities that BADS members would consider travelling to for a BADS Conference

(it was possible to choose more than one option)

We have taken note of the survey responses and will be keeping our BADS ASM as a 2-day conference. In 2018 at the Sheffield conference we will be moving to an electronic programme with a paper daily schedule and have not increased the conference fees. If you have any further comments or would like to be a local organiser then please contact bads@bads.co.ukThere were also a number of suggestions for London (11), places along the South Coast and Scotland. For those of you that mentioned Yorkshire and Sheffield we hope to see you on 21st & 22nd June this year. For those that mentioned Leeds, York, Harrogate, Nottingham or Manchester we hope that Sheffield is not too far for you to attend the conference in June 2018.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6183/281-survey.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse2

The Journal of One-day Surgery considers all articles of relevance to day and short stay surgery. Articles may be in the form of original research, review papers, audits, service improvement reports, case reports, case series, practice development and letters to the editor. Research projects must clearly state that ethics committee approval was sought where appropriate and that patients gave their consent to be included. Patients must not be identifiable unless their written consent has been obtained. If your work was conducted in the UK and you are unsure as to whether it is considered as research requiring approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), please consult the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool at http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Articles should be prepared as Microsoft Word documents with double line spacing and wide margins. Submissions must be sent by email to the address below. A scanned letter requesting publication signed on behalf of all authors must also accompany articles.

Any source of funding should be declared and authors should also disclose any possible conflict of interest that might be relevant to their article.

Title Page

The first page should list all authors (including their first names), their job titles, the hospital(s) or unit(s) from where the work originates and should give a current contact address for the corresponding author.

The author should provide three or four keywords describing their article, which should be as informative as possible.

Abstract

An abstract of 250 words maximum summarising the manuscript should be provided and structured as follows: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions.

Main article structure

Manuscripts should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and References. Tables and figures should follow, with each on a separate page. Each table and figure should be accompanied by a legend that should be sufficiently informative as to allow it to be interpreted without reference to the main text.

All figures and graphs are reformatted to the standard style of the journal. If a manuscript includes such submission, particularly if exported from a spreadsheet (for example Microsoft Excel), a copy of the original data (or numbers) would assist the editorial process.

Copies of original photographs, as a JPEG or TIFF file, should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedding pictures within the text of the manuscript.

References

References should be cited numerically in the order in which they appear in the text. References should list all authors' names. Please provide both the first and last page numbers.

Authors. Article title. Journal title Year of publication;Volume (in bold):page range.

Example reference

Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281

Submissions are subject to peer review. Proofs will not normally be sent to authors and reprints are not available.

All items should be emailed to The Editor: davidbunting@nhs.net

Mr David Bunting

Editor, Journal of One Day Surgery

Consultant Upper GI Surgeon

North Devon District Hospital

[These guidelines were last revised on 20.02.2018]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6188/281-authors.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse3

Authors

Navreen Chima Clinical Fellow in Anaesthesia, Department of Anaesthesia, Royal United Hospitals Bath NHS Foundation Trust, Royal United Hospital, Combe Park Bath BA1 3NG.

Tel: 07951709820 . Email:navreenchima@nhs.net

Jane Montgomery Consultant Anaesthetist, Department of Anaesthesia, Torbay Hospital, Torquay.

Key Words: Perioperative pain, day surgery, audit.

Abstract

Introduction Increasing numbers of patients are living with chronic pain conditions and are regularly utilising opioid based analgesics.1, 2, 3 These patients have been identified as at risk of severe postoperative pain.4, 5, 6, 7 We have reviewed the effect of preoperative pain on progression through the day surgery pathway, and on compliance with national targets in day surgery as proposed by the Royal College of Anaesthetists.

Methods We conducted a one-year retrospective analysis of all patients treated through our day surgery unit. 12 620 patient records were reviewed. 84 were deemed to be high risk of peri-operative pain based on a four-question screening tool previously validated for patients undergoing inpatient surgical procedures.8

Results There were no unplanned admissions related to pain in this high-risk group. Only two patients had severe pain at 24 hours and required further medical input, which is well within agreed national standards. Six had a numerical pain score greater than zero upon discharge from primary recovery and had all undergone orthopaedic procedures. All patients had positive satisfaction ratings following their experience.

Conclusion . This audit suggests that chronic pain should not be a barrier to day case surgery and that standards of care remain mostly compliant with national targets in this challenging patient population.

Introduction

It is well described that both the prevalence of chronic pain and the use of long term opiates is increasing amongst our population.1, 2, 3 This presents a potential problem for how we plan perioperative care for this patient subgroup. There is a suggestion that these patients are at risk of worst postoperative pain experiences and that they require additional input from specialised services such as the acute pain team.4,5,6,7 This difference would suggest that they are more likely to require inpatient care to successfully manage their pain.

At Torbay Hospital patients are screened at preoperative assessment for risk factors indicative of an increased risk of difficultly controlling pain during the postoperative period. This is assessed utilising a four question screening tool previously validated for inpatient surgery at this hospital.7 These risk factors are; a history of chronic pain syndrome, anxiety related to postoperative pain, previous poor postoperative pain control, and double weighting is given to the use of long term opiates. The presence of two or more of these factors was shown to be directly related to both higher postoperative pain scores and increasing input from the acute pain services. A positively weighted result from the screening tool triggers referral to the acute pain services but does not prevent the patient being referred to and undergoing ambulatory surgery.

Aims

We set out to identify whether patient outcomes in this high-risk group are falling outside agreed standards of care for day surgery and, therefore, whether these patients should be referred for inpatient surgery to optimise their perioperative experience.

Standards

The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA) has proposed standards of care related to ambulatory surgery.8 It is stated that:

- The admission rate following day surgery should be locally agreed but targeted to less than 2%.

- Fewer than 5% of patients should report severe pain within the first 48 hours of discharge.

- At least 85% of patients undergoing day surgery should have ‘none’ or ‘mild’ pain following discharge.

- At least 85% of patients should be ‘satisfied’ with their management of pain in day surgery.

Methods

To assess whether this patient population were meeting the described standards of care for day surgery, we carried out a retrospective review of 12 620 patients who passed through the day surgery unit at Torbay Hospital. Patients were captured through visits to the preoperative assessment unit from January to December 2016.

Patient risk factors for postoperative pain were documented on PICIS © preoperative manager. We selected all those patients with positively weighted preoperative screening results. This totalled 84 patients who had a presence of two or more risk factors for difficulty in managing postoperative pain.

Data was collected on postoperative outcomes from our theatre system Galaxy (DXC.technology). This included primary recovery pain scores, discharge analgesia and patient outcomes elicited from a telephone call on day one after surgery.

Results

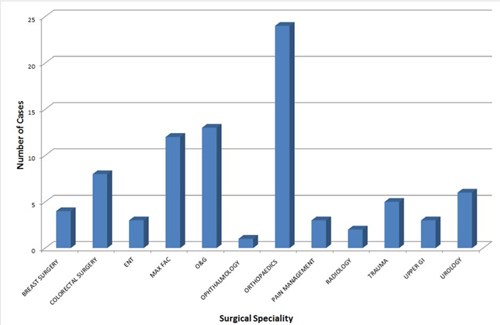

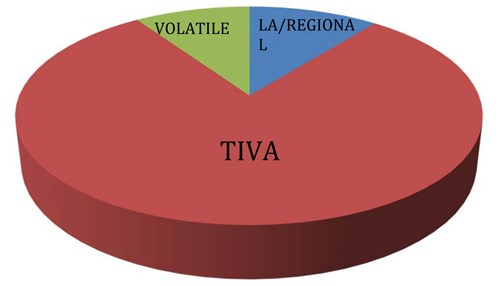

The procedures carried out spanned a range of surgical subspecialties and were representative of a district general hospital (Figure 1). The anaesthetic techniques used intraoperatively were representative of those commonly used in the day surgery unit at Torbay Hospital (Figure 2).

Figure 1: Subspecialty surgeries carried out in Torbay Hospital for patients at risk of difficult postoperative

pain control during 2016.

Figure 2: Anaesthetic techniques uses in Torbay Hospital day surgery unit for patients at risk

of difficult postoperative pain control during 2016.

Only one patient needed hospital admission overnight. This was required due to mobility difficulties and was independent of pain. This is well within the 2% admission rate thought to be acceptable by the RCOA and falls at 1.2%.

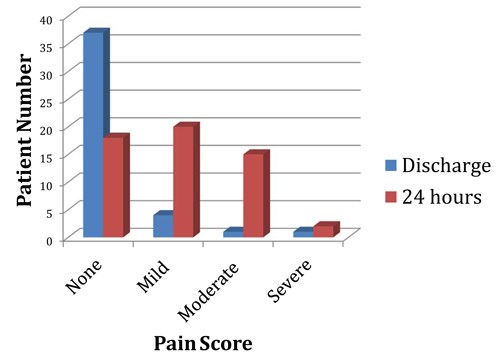

Pain scores at discharge from the primary recovery were only available for 51% of patients. 95% of these patients reported none or mild pain at this point in their journey (Figure 3). All but six patients were discharged home with a pain score of zero. These six patients had all undergone orthopaedic surgery but continued to successfully complete the pathway without adverse outcomes.

The discharge analgesia patients receive is automatically formulated based on procedure. The data showed that only four patients in the high risk pain group had this analgesia modified.

Follow-up contact is routinely made as part of our day surgery service at Torbay Hospital and 65% of this high risk patient group responded to contact within the 24 hour postoperative period. They answered questions regarding their well being which provided more information on the perioperative pain experience (Figure 3).

Figure 3: Verbal pain rating score reported at time of discharge from primary recovery and at

24-hour follow-up by patients at risk of difficult postoperative pain control during 2016 in Torbay Hospital

day surgery unit.

During follow-up only two patients reported severe pain that required further medical input. This falls at a rate of 2.4% and meets the set criteria of less than 5% of patients verbally reporting adverse pain scores. Despite this positive result, severe pain was reported greater than six times more frequently than the entire years patient group, which fell at a rate of 0.4%. Both patients reporting severe pain at follow-up underwent laparoscopic gynaecological surgery. Severe pain did not appear to be related to this specific procedure as eleven other patients also had Obstetric/Gynaecological procedures and up to 40% of the group underwent laparoscopic surgery and did not report severe postoperative pain.

The follow up phone call also revealed that 38 of the 55 responders reported ‘none’ or ‘mild’ pain on the verbal rating scale. This is just 69% of those contacted and falls outside the targeted 85% of patients having low pain ratings following discharge.

Satisfaction with the service was greater than expectations set by the RCOA. 100% of responders described being satisfied or very satisfied with their overall experience of day surgery and their care.

In addition to the parameters suggested by the RCOA, we also looked into the utilisation of the pain services. This had previously been shown to be high in this patient population.7 However, in the context of ambulatory surgery, none of the patients required input from specialised services prior to discharge home and the acute pain team were not recruited to assist with immediate postoperative care in any of the cases.

Discussion

This audit suggests that chronic pain does not adversely affect the progression through the day surgery pathway and produces positive patient experiences. There is also a suggestion that postoperative pain predictors do not hold the same validity in the ambulatory setting where patients are encouraged to be in control of their own analgesia, or may be undergoing less invasive surgery.

The admission rate of 1.2% within the group occurred independently of pain. This fell lower than the year’s overall admission rate of 1.8% based on data collected from 12 120 patients. Of this year’s sample, 28 of the admissions were related to pain despite having no significant patient risk factors for adverse pain outcomes. This demonstrates that patients in whom we predict difficulty in controlling postoperative pain may actually go on to have better pain control postoperatively compared with our general patient population.

From our results more patients in our high-risk population described ‘moderate’ pain after discharge. This may mean they need increased support to reach the targeted day surgery standards. However, the follow-up in Torbay is completed the day after surgery rather than the 48 hour time frame suggested by the RCOA. This would have impacted on the pain levels reported and may negatively skew outcomes. We also know that these patients suffer with pain preoperatively and it may be that this ‘moderate pain’ is their everyday experience. Unfortunately we do not have their preoperative pain scores. It may be worthwhile in future work to compare the preoperative and postoperative pain scores to establish whether these patients are in need of further support.

We accept that the telephone response rate provides incomplete data on follow-up pain scores. The limited response may skew data in that those in pain may not have been able to access the phone, but equally those who did not answer the phone may have been comfortable enough to leave their house. Given this, it is likely that the responders represent a cross-section of the high-risk group. A prospective study could be considered in future work to overcome this limitation and gain a more comprehensive picture of pain levels at 24 to 48 hours. Though not an RCOA proposed standard, a prospective study would also overcome the incomplete data capture within the recovery setting. This is likely to be incomplete due to high clinical workload. This workload may have included addressing pain issues that were not captured in our data set, potentially skewing the pain score at this point in the patient journey.

The follow-up pain scores occurred in the context of 95% of the patients being discharged with a standardised analgesia prescription, unmodified for their risk factors for difficult to control pain. It is worth noting that that this data was derived from the electronic record upon immediately leaving theatre and so discharge analgesia may have been altered at a later point based on recovery experiences. Considering all of this, there may be a benefit in prescribing rescue discharge analgesia to aide comfort in the patient group, and to provide more explicit advice for help with pain management.

This audit also encourages re-consideration of discharge analgesia for this patient subgroup when having specific types of surgery, namely gynaecological and orthopaedic surgery. This audit data does not give an understanding of intraoperative modifications of anaesthetic technique that may alter outcomes such as a greater tendency for regional blocks or local anaesthetic use. Despite this, it is evident that those with multiple risk factors for postoperative pain and having orthopaedic or gynaecological surgery are most likely to need additional analgesic measures upon discharge.

Our audit also has implications for acute pain services in Torbay Hospital and implies that we should not be routinely referring chronic pain sufferers to the acute pain team. This would reduce their work load burden considerably and is a planned change within our department.

These results have helped to encourage both surgical and anaesthetic teams in Torbay Hospital to undertake day surgery in this patient group. A patient information leaflet for chronic pain suffers will support this. This will advise these patients more specifically on their medication management, pain expectations and guidance for help.

Currently the preoperative visit summary alerts the Anaesthetist to the patient with multiple risk factors for poor postoperative pain experience but there is still scope to set up an alert on the electronic discharge prescription to encourage rescue analgesia for improved home pain management.

Conclusion

This audit of a district general hospital day surgery unit suggests that the presence of chronic pain should not be a barrier to day case surgery. These patients generally meet nationally recommended targets and show high satisfaction levels when undergoing ambulatory surgery, perhaps due to their greater autonomy over pain management.

References

- Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford R M, Donaldson L J, Jones G T, Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies, BMJopen, 2016, 6(6). Available from: http://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/6/6/e010364 [accessed 14th February 2018]

- Cartagena Farias J, Porter L, McManus S, Strang J, Hickman M, Reed K, Smith N. Prescribing patterns of dependence forming medicines - analysis using the Clinical Practice Research Database, 2017. Available from: http://phrc.lshtm.ac.uk/papers/PHRC_014_Final_Report.pdf [accessed 14th February 2018]

- NHS England, 2018, Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/article/4214/Prescribing [accessed 14th February 2018]

- Lewis L, Williams J, Acute pain management in patients receiving opioids for chronic and cancer pain, Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care and Pain, 2005, 5(4):127-129

- Gramke H F, De Rijke J M,Van Kleef M, Kessels A G, Peters M L, Sommer M, Marcus M A, Predictive factors of postoperative pain after day-case surgery, The Clinical Journal of Pain, 2009, 25(6), 455-60

- Sommer M,De Rijke J M, Van Kleef M, Kessels A G, Peters M L, Geurts J W, Patijn J, Gramke H F, Marcus M A, Predictors of acute postoperative pain after elective surgery, The Clinical Journal of Pain, 2010, 26(2), 87-94

- Magides A, Carter S, Day R, Natusch D, Do pre-operative screening questions on pain predict a worse post-operative pain experience? An exploratory audit, British Journal of Pain; 2013, 7(2 Suppl):5–76

- Royal College of Anaesthetists, 2012, Raising the Standard, a compendium of audit recipes, Available from: https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/CSQ-ARB-2012_0.pdf [accessed 19th February 2018]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6184/281-chima.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse4

Authors

Miss Felicity Pagea, Ms Mary McCarthya, Mr Darren Chestera

Miss Felicity Page Plastic Surgery Registrar

Ms Mary McCarthy Hand Unit Coordinator

Mr Darren Chester Hand and Plastic Surgery Consultant. Plastic Surgery Department and Birmingham Hand Centre, Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Mindelsohn Way, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2GW

Corresponding Author Miss Felicity Page Plastic Surgery Department, John Radcliffe Hospital, Headley Way, Oxford OX3 9DU

Email: felicitypage@doctors.org.uk Phone: 01865 741166

Abstract

Introduction In 2003, the University Hospital Birmingham introduced a day case emergency hand trauma operating system1. Appropriate patients are identified at assessment in accordance with strict selection criteria and return for their operation on dedicated hand trauma theatre lists. The service has been shown to improve efficiency and reduce patient complaints1.

Aims The aim of the study was to assess clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction with the service.

Methods Feedback questionnaires were distributed prospectively to patients on emergency hand trauma operating lists. Patients were contacted by telephone and case notes were reviewed at 30 days post operatively. Analysis included patient demographics, injury sustained, operative management, complications and satisfaction results.

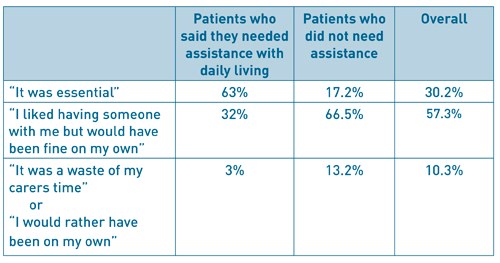

Results Results were collected for 100 patients. Overall 93% would recommend the service. There were high levels of satisfaction with all aspects, including information provided (93%), pain management (83%) and comfort going home (86%). The vast majority did not need any further medical input prior to surgery.

99% were supplied with antibiotics in accordance with management protocols. 1.5% of patients with open injuries were treated for a post-operative infection. The mean time between assessment and operation was 2 days.

Conclusion This study has shown that semi-elective day case hand trauma surgery is safe and effective as demonstrated by the low infection rates and high levels of patient satisfaction.

Keywords: Hand, satisfaction, infection

Conflict of interest statement None

Funding declaration None

Introduction

In 2003, the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham (formerly Selly Oak Hospital) introduced a day case emergency hand trauma operating system.1 The service was designed to improve patient care in response to published data on inpatient hospital delays for those awaiting hand trauma surgery and prolonged overall hospital stay for these patients.2 Patients could often be kept nil by mouth for extended periods of time whilst awaiting their surgery on the joint emergency list, elective cases were also being cancelled due to high bed occupancy by hand trauma patients awaiting surgery. As a result service provision was transformed with patients being sent home and re-admitted semi-electively onto dedicated operating lists. This service was therefore a novel way of managing patients with open injuries and has revolutionised the care of these injuries. It has also reduced the number of cancelations of elective operations due to bed occupancy by hand trauma patients. Validation of the service is important as this approach is now being used in a number of units.

All hand trauma patients are assessed in the Emergency Department. Those considered appropriate for semi-elective day-case procedures are identified in accordance with strict selection criteria. Severe or complex injuries, open fractures, significantly contaminated wounds and bite wounds are not considered appropriate. Patients with significant comorbidities, deliberate harm injuries or those considered unreliable for example drunk patients are also not appropriate. Closed fractures, simple lacerations with suspected tendon or nerve divisions and fingertip injuries are suitable.

Following assessment, antibiotics are prescribed in accordance with the trust protocol and analgesic requirements are reviewed. Wounds are thoroughly washed out in the Emergency Department, frequently under local anaesthetic. Suitable patients are able to go home and return for their operation on a dedicated hand trauma theatre list. Hand unit coordinators (senior nurses) are crucial to the running of the service and are a point of contact for patients.

The hand trauma day surgery unit has been shown to improve efficiency, reduce patient complaints1, reduced in-patient delay and total stay.2

The aim of the study was to assess clinical outcomes and patient satisfaction with the service. Given that this service is novel and involves delayed surgery, the authors sought to specifically evaluate infection rates.

Methods

A feedback questionnaire was designed in collaboration with the Trust Audit and Research Department (Figure 1). The questionnaire was distributed prospectively to patients on emergency hand trauma operating lists.

Respondents to the questionnaire were contacted by telephone and a review of case notes was performed at 30 days post operatively. Infection postoperatively was diagnosed according to the Centre of Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) criteria.3 Analysis included patient demographics, injury sustained, operative management, complications and satisfaction results. Local ethics and audit procedures were complied with.

Results

Results were collected for 100 patients in total over 23 operating days. 126 patients were approached, 18 declined, 1 patient was excluded due to a language barrier and 7 patients did not undergo an operation. The mean age was 38 years and 10 months (range 16 years 10 months – 75 years 3 months), 80 patients were male and 20 female.

Overall 93% of patients would recommend the service. There were high levels of satisfaction with all aspects, including information provided (93%), pain management (83%) and comfort going home (86%)(Table 1). The vast majority did not need any further medical input prior to surgery (91%). Those that did, sought further medical attention for replacement of bandages (4%), pain and swelling (4%), and ‘feeling unable to cope’ (1%). No patients required admission prior to their planned operation date. Approximately half of patients could recall being given a telephone number to contact if they had any concerns at home (56%). The vast majority felt that they were given clear instructions for the arrangements on the day of their surgery (93%). 95% of patients would not have preferred to stay in hospital until their operation.

99% of patients were supplied with a course of antibiotics as per the antibiotic management protocol. 68 patients were followed to assess post-operative infection rate, these included all patients with open hand injuries who were contactable by telephone at 30 days post operatively. One patient (1.5%) was treated for a post-operative infection. This patient underwent K-wiring of a distal phalanx fracture and nail bed repair, there were no concerns at initial follow up in the hand surgery department and the patient had completed their prescribed antibiotic course. The post-operative infection was diagnosed by the General Practitioner and managed with further oral antibiotics.

For the 68 patients with open injuries, the mean time between injury and presentation was 0.6 days (range 0–6 days). The mean time between presentation and surgery was 2.1 days (range 1–5 days) and the overall mean time between injury and surgery was 2.7 days (range 1–9 days).

Discussion

This study has shown high patient satisfaction rates with all aspects of the day case hand trauma surgery service. With a unanimous agreement that patients would be happy to use the service again if required. This has been the first published review of patient satisfaction following the introduction of a dedicated hand trauma day-case unit for managing both open and closed injuries, which has now been adopted in a number of units across the country.

With 95% of patients preferring not to be admitted to hospital whilst awaiting their surgery, the service is clearly more convenient for the majority, who would have previously required hospital admission.

Pain management at home was generally good with 92% agreeing that their pain was well controlled. Those who did not feel their pain was controlled well (8%) all had analgesia prescribed when discharged following their initial assessment. These injuries included fingertip lacerations, a laceration with a suspected digital nerve injury and a distal phalanx closed fracture.

Generally patients felt well informed about the arrangements for their operation (97%). All patients are provided with an information leaflet with further details about what to expect, how to contact the department and how the service is run. A minority of patients did not find it convenient to travel back for their operation (11%), however if there are concerns that patients will not re-attend for their operation they are admitted following assessment, alternatively hospital transport can be arranged.

Although overall satisfaction was still very high, the questionnaire has enabled identification of areas for further improvement. These include the need to reiterate information to patients on what they should expect when they go home, the need to ensure patients are aware of the department contact telephone number and make sure they are supplied with written information to reinforce verbal information. The importance of ensuring a supply of analgesia was also highlighted. This feedback has been distributed throughout the department.

Antibiotic prescription was carried out in accordance with the clinical guidelines for 99% of patients. The infection rate was low (1.5%) when compared to other published infection rates for elective and hand surgery 4. Whilst it is possible that infections can be missed, we believe that our methodology kept this to a minimum by not only checking hospital medical records but also contacting patients at 90 days. This study therefore supports the concept that thorough wound washout and antibiotics will allow semi-elective hand surgery without increasing infection rates.

The mean time between assessment and undergoing surgery was 2.1 days. When taking into account the delay in patient presentation, time between injury and operation remained on average between 2-3 days, which is keeping with previously achieved timeframes2. This timeframe does not appear to have any detrimental effects on infection rates and was not highlighted as a concern by any patients within the satisfaction survey.

Success of the hand day-surgery unit is likely to be attributable to a number of factors including appropriate patient selection, adherence with antibiotic guidelines and the employment of dedicated senior nurse hand coordinators who help run the service and provide a point of contact for patients.

This study has shown that semi-elective day case hand trauma surgery is safe and effective as demonstrated by the low infection rates and high levels of patient satisfaction.

Figure 1 –feedback questionnaire completed by patients

References

- BSSH. Hand Surgery in the UK: manpower, resources, standards and training. 2007. Available at http://www.bssh.ac.uk/members/documents/ukhandsurgreport.pdf [accessed 22/11/2015]

- Dillon CK, Chester DL, Nightingale P, Titley OG. The evolution of a hand day-surgery unit. Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 2009;91(7):559.

- Mangram AJ, Horan TC, Pearson ML, Silver LC, Jarvis WR, Hospital Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection, 1999. American journal of infection control. 1999;27(2):97-134.

- Aydin N, Uraloglu M, Burhanoglu AD, Sensöz Ö. A prospective trial on the use of antibiotics in hand surgery. Plastic and reconstructive surgery. 2010 Nov 1;126(5):1617–23.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6185/281-page.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse5

Authors

Dr Johannes Retief Anaesthesia Registrar, Department of Anaesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Lowes Bridge, Torquay, TQ2 7AA.

Email: jretief@nhs.net Tel: 07919 363 563

Dr Rachel Morris Consultant Anaesthetist, Department of Anaesthesia, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Colney Lane, Norwich, NR4 7UY.

Email: rachel.morris@nnuh.nhs.uk Tel: 01603 286 286

Dr Mary Stocker Consultant Anaesthetist, Department of Anaesthesia and Perioperative Medicine, Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust, Lowes Bridge, Torquay, TQ2 7AA

Email: mary.stocker@nhs.net Tel: 01803 654 159

Keywords: Postoperative carer, 24-hour care, day case discharge

Abstract

Introduction: Having a responsible adult with you for 24 hours after day surgery remains an absolute eligibility criterion for day surgery in the large majority of centres. However, with advances in anaesthetic and surgical techniques, as well as a shortage of inpatient capacity, this is increasingly being challenged for some patients. We reviewed the literature available and present a summary of our findings. We also describe two alternative options to inpatient care for those patients who are not able to provide their own carer.

Methods: A MEDLINE database search was performed. Guidelines from different anaesthesia bodies were obtained from their respective websites. Archives from the Journal of One Day Surgery were also searched. Practical solutions are described which have been pioneered in the units where the authors work.

Results: Guidelines from five different anaesthesia bodies, seven studies utilising patient questionnaires or surveys, three surveys of practice and three review or other articles are discussed. Two examples of managing patients with no carer is available are also described.

Conclusion: There is a wide variation in practice in this area of day surgery, both in terms of what the patients choose to do (despite instructions) and what different departments recommend. Day surgery units should have dynamic policies in place and seek innovative solutions when faced with patients who do not have overnight care.

Introduction

Having a responsible adult with you for 24 hours after day surgery remains an absolute eligibility criterion for day surgery in the large majority of centres. However, with advances in anaesthetic and surgical techniques, this is increasingly being challenged for some patients. Also, in the current climate of bed shortages in United Kingdom (UK) hospitals alternative arrangements need to be found to for patients without 24-hour care at home. We reviewed the literature available and present a summary of our findings. There is no conclusive evidence about whether a carer is needed postoperatively and for how long. We also describe two different local practices that are in place for patients who are not able to provide their own carer. In one centre, overnight care can be arranged for patients who are not able to provide family or friends to stay with them. In the second example, overnight care is no longer mandated for certain eligible patients, should they be unable to provide a carer. Day surgery units should have dynamic approaches when faced with patients who do not have overnight care. Clarification of terminology between carer and escort is important. An ‘escort’ generally refers to a person who accompanies the patient from the hospital to their home. Unless specified, this differs from the ‘overnight carer’ or ‘postoperative carer’, who is the person that stays with the patient overnight or for 24 hours. We mainly consider the latter but, as there is often some overlap, literature regarding patient escorts will be considered when relevant.

Methods

Searches of the MEDLINE database and archive of the Journal of One Day Surgery were conducted using a wide variety of search terms which encompassed day surgery, carer, responsible adult and care at home. In addition, guidelines from a range of international and national anaesthesia bodies were obtained directly from their respective websites. Examples of practice described are from the authors’ units with previously unpublished data presented. These results have been previously presented at British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) Annual Scientific Meetings [1, 2].

Results

The literature review on this subject can broadly be divided into four categories:

- National and international guidelines

- Patient questionnaires and surveys

- Surveys of practice

- Review and other articles

Each of these will be considered in turn below. We also describe two different approaches employed by day surgery units for patients who are not able to provide their own overnight care.

National and international guidelines

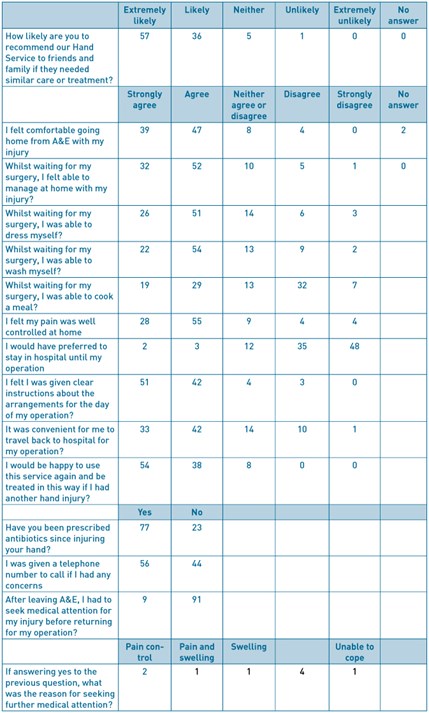

Table 1 gives an overview of guidelines from several countries. In general, a carer postoperatively is still recommended. However, the arbitrary time frame of 24 hours is not universally mandated. The Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA) produce Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services (GPAS) [3]. In the chapter regarding provision of anaesthesia services for day surgery, it is interesting to note the following statement: “A carer may not be essential if there has been a good recovery after brief or non-invasive procedures and where any post-operative haemorrhage is likely to be obvious and controllable with simple pressure”. This, together with the word ‘most’ in the joint Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland (AAGBI) and British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) guidelines [4] gives some indication that a blanket rule may not be appropriate for all patients.

Table 1: Guidelines pertaining to day surgery for different countries and extracts from sections

regarding the postoperative carer

Patient questionnaires and surveys

Fahy and colleagues investigated the practicality of conducting post-anaesthetic follow-up by questionnaire [9] after finding that interviewing patients was expensive and difficult. With a 96% response rate, this was shown to be a useful research tool and has been used extensively in the day surgery population since. Ogg, a founding member of BADS, utilised a patient questionnaire to gauge patient outcomes 48 hours after day surgery [10]. Unfortunately, it did not specifically ask about an overnight carer. However, of interest is that 31% of patients made the journey home alone with 9% of patients driving themselves. 30% and 43% drove within 12 and 24 hours respectively.

A Canadian telephone survey of 750 day surgery patients [11] found that although all patients were escorted out of the hospital, 29 patients (4%) had no one staying with them overnight. However, there is no information regarding whether these patients had any problems in that period. This was followed by a telephone survey in the UK regarding compliance with post-operative instructions [12]. 240 patients at three different hospitals were telephoned at 24 to 48 hours postoperatively. Although all the patients were discharged into the care of a responsible adult, 32 patients (13.3%) failed to have a carer for 24 hours and three patients (1.3%) spent the night alone. From one centre, the mean time a carer spent was 19 hours. They raised the issue that there were few guidelines on the role of the carer or how much supervision was required. They also recommended that further studies need to establish the necessity of 24-hour care post-operatively.

Another telephone survey looked at the issue of how long a carer stayed post-discharge and explored the patients’ views on the subject [13]. The data was analysed according to procedure complexity, stratified according to anticipated pain score. There was a stepwise increase in the time it took for patients to feel ‘safe’ as the complexity increased, with a statistically significant increase in the time taken to feel safe between the ‘no anticipated pain’ group and ‘severe anticipated pain’ group. They enquired after the patients’ opinion of the 24-hour recommendation (Table 2). Overall, 59% of patients felt the 24-hour recommendation for a carer was ‘about right’. However, when analysed according to expected pain levels (reflecting procedure complexity), it is clear that patients with expected pain of moderate or severe may in fact feel that 24 hours is not enough. This was not the case in those with expected pain of ‘none’ or ‘mild’ many of whom felt that the requirement for 24 hours postoperative care was too long.

Table 2: Patients opinion of the 24-hour recommendation, grouped according to expected pain levels

(based on procedure complexity and experience).

Adapted from: Barker J, Holmes K, Montgomery J, et al. How long is 24 hours? A survey of how long a carer stays with the patient post discharge. Journal of One-Day Surgery. 2014. 24(2): 57-60.

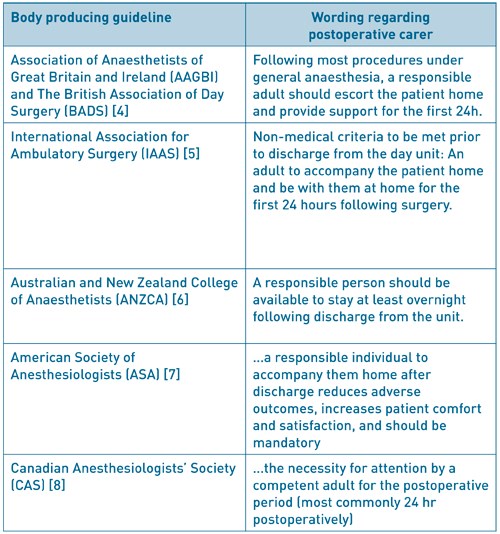

A further study utilised postal surveys to evaluate the compliance with 24-hour adult supervision and found an overall non-compliance rate of 18% (62 out of 351 patients) [14]. The length of time the carer stayed in this case varied, with 9 patients admitting the carer stayed for less than one hour. 15 patients (4%) experienced problems which required medical help but only two of these patients said they needed the carer to obtain the help (to contact ambulance or general practice (GP) services). They also asked about the patients’ attitudes towards having a carer stay with them (see Table 3). Overall only 30% felt it was ‘essential’. However, of those that required help with daily living (99/351; 28%), 63% felt it was essential. A large proportion of patients liked having someone with them but were of the opinion that they “would have been fine on my own”. 10% of patients felt that it was either “a waste of my carer’s time” or “I would rather have been on my own”.

Table 3: Patients answers to the question: “How did you feel about having an adult stay with you

for 24 hours after surgery?”.

Adapted from: Wessels F, Kerton M, Hopwood H. Evaluating the need for day surgery patients to have 24 hours of adult supervision postoperatively. Journal of One Day Surgery. 2015. 24(4): 17-23

In 2014 the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital surveyed 100 day case patients over a 2-week period by questionnaire, with a 64% response rate [2]. The two main aims were to gather information about how many patients, who might be safe at home alone, do not have a carer available and whether patients felt they would need assistance at home after their surgery (and if so, why). Laparoscopic and airway surgery patients were excluded as it was felt they would not be safe at home alone after surgery. Paediatric patients were also excluded. 8 responses were excluded (unplanned admissions, laparoscopic surgery and 1 blank form). The survey showed that the majority of the remaining surveyed patients (66.6%) had a carer for at least 24 hours and 33.3% did not. One of the questions asked was ‘whether the patients felt they needed assistance at home postoperatively?’ 59% of patients felt they would need a carer present after surgery. However, the main reason patients wanted assistance at home was for support, with no anaesthetic or surgical complications reported. 41% felt they did not need assistance at home post operatively. 5 of the patients surveyed lived alone and 4 of them said they would not need assistance. The one patient that said they needed assistance had lower limb metal work removal and found mobilisation difficult. Two patients who had eye surgery both felt they needed assistance due to impaired vision. This was taken into account when writing the self-care pathway. The survey confirmed that patients were making decisions about how much care they felt they needed postoperatively. This is in line with the evidence presented in the rest of the article. The vast majority of patients want and are able to arrange someone to be present for the following 24 hours after discharge. However, some patients do not and therefore a Self-Care Pathway was designed, discussed below.

Surveys of practice

A survey of Canadian anaesthetists with 774 replies (57.8% response rate) found that 11.2% would anaesthetise a patient despite knowing the patient had no escort [15]. It is unclear whether they would then expect the patient to be admitted but some of those in this group did add that they would only agree if a patient signed a release form. An international survey of 100 centres in 8 European countries had a response rate of 70% [16]. Routine demand for an escort varied widely between countries, from 36% to 100%. Routinely securing someone to be at home for the first post-operative night was done by 81% of centres but ranges from two thirds to 100%. Despite contacting the authors, we were unfortunately not able to get the UK specific data for this particular area of practice. The same group sent questionnaires to all 92 hospitals in Sweden, particularly looking at the clinical practice and routines for day surgery [17]. In this survey, 27/73 units (37%) did not insist on an escort at discharge but it did not report on the requirement for 24-hour, or overnight, care.

Review and other articles

In 2009, Ip and Chung examined the most recent findings as to whether an escort after ambulatory surgery is a necessity or luxury [18]. Although the term escort is used, they make the point that ‘the role of an escort should be more than merely providing the patient with the ride home’. They recommend that patients without an escort should either be rescheduled or admitted to a 23-hour care bed post-operatively.

In a summary article by Abdullah and Chung regarding discharge criteria for ambulatory surgery [19], citing three malpractice cases of car accidents after ambulatory surgery [20], they recommend that patients should be made aware of the importance of having a responsible adult escort them home and stay with them overnight.

A prospective study [21] over a 38-month period collected data on patients with no escort at a day surgery unit in Toronto. They defined ‘no escort’ as not having a responsible individual to accompany the patient home. Out of 28,391 patients, 60 patients (0.2%) had no escort. They identified two groups in this cohort: those who were known to have no escort (24 patients) and those whose escort did not show up (36 patients). Five of these patients had their surgery cancelled but the remainder underwent surgery. Those with no escort were offered admission but if this was not possible, risks were explained and a self-discharge form signed. Of note, 28.2% of those with no escort also had no overnight care. Outcomes of the no escort group were compared to a matched control group that did have an escort and no differences were found in rates of unanticipated admission, emergency visits or readmission within 30 days.

Alternative solutions to inpatient care for patients without home care

Patients who do not have overnight care available, for example from family or friends, are often admitted to hospital overnight. Not only does this incur cost to the trust and occupy an inpatient bed, a precious resource in the current climate, but patients are not able to reap all the benefits that day surgery provides. In addition, the vast majority of patients would prefer to recuperate in their own surroundings if at all possible.

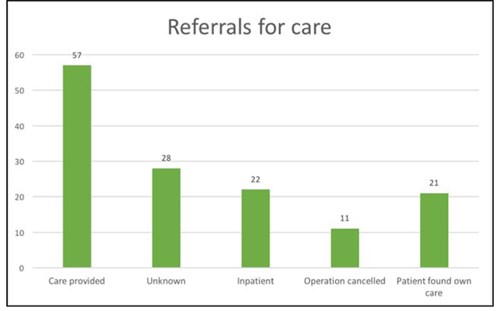

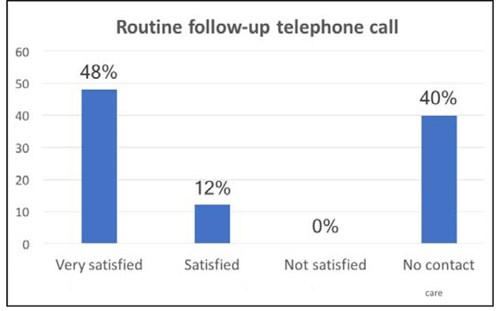

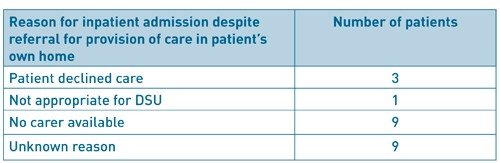

The Torbay Experience: Provision of a carer

In the Torbay Day Surgery Unit, patients who are unable to arrange overnight care are offered a carer to stay with them for the first postoperative night (at no cost to the patient). This means the patients and hospital continue to benefit from the established day surgery pathway. It is more cost effective for the trust (£100-£150 versus £300 estimated cost of an inpatient stay) and releases valuable inpatient beds for those more in need of this resource. Eligible patients are identified at the pre-operative assessment clinic and details given to a hospital discharge coordinator. This person then liaises with relevant care agencies and the patient to arrange overnight care. Between April 2014 and February 2017, 139 such referrals were made (Figure 1). 57 (41%) had a carer provided, of interest, 21 patients (15%) who initially had no care managed to find care from family and friends. 11 patients had their surgery cancelled for reasons other than post-operative care and 22 patients still needed admission for varying reasons (Table 4). Unfortunately, occasionally, the agencies do not have carer availability (9 patients in this period). Very few patients (3) declined the option of provided care, resulting in hospital admission. On routine post-operative telephone follow up, all the patients who were contacted were satisfied with their overall day surgery experience, including post-operative care (figure 2).

Having a system in place to provide patients with overnight care following day surgery can be a cost effective and beneficial alternative to admission to hospital. There is a reduction in inequality of care and more patients are able to benefit from day surgery. In addition, the use of an inpatient bed, a precious resource, may be avoided.

Figure 1: Numbers of patients referred for provision of a carer at Torbay Hospital Day Surgery Unit

(April 2014 – February 2017).

Figure 2: Overall satisfaction of day surgery experience for patients who have had carer provided overnight

at Torbay Day Surgery Unit.

Table 4: Reason for inpatient admission despite referral for provision of a carer at Torbay Day Surgery Unit.

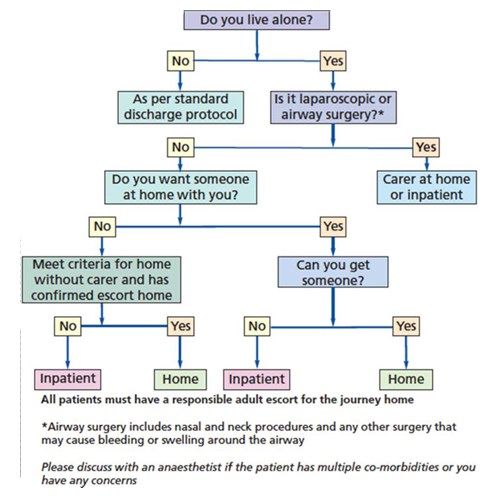

The Norfolk and Norwich Experience: The Self-Care Pathway

Like all hospitals the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital has problems with lack of inpatient beds and it is important to ensure patients are only admitted overnight when absolutely necessary. A regular reason for admission after surgery suitable for same day discharge is patients who live alone and are unable to find someone to stay with them for 24 hours. To ensure effective use of inpatient beds and to enable day surgery to be an option for all patients it was decided to explore ways that patients who live alone could have their operation without an inpatient stay. After the survey (see above) and review of the literature it was decided that for some patients having certain procedures that it would be safe for them to go home without a carer.

A pathway was therefore developed that balanced the risks of surgery and patient’s wishes, to allow suitable patients to return home with no carer in place (Figure 3). Criteria for patients to meet self-care pathway includes:

- Safe surgery for home alone

- Patient would like to go home alone

- No comorbidities excluding patients from day case

- Need an escort home in private car

- Decision made in preoperative assessment clinic

Figure 3: Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust ‘Self-Care Pathway’

following day surgery.

The criteria for patients to meet the self-care pathway are:

- Safe surgery for home alone

- Patient would like to go home alone

- No comorbidities excluding patients from day case

- Need an escort home in private car

- Decision made in preoperative assessment clinic

Added benefits, for the pathway, include no cost implications for the hospital and a reduction in admission rates. The planning for this is all done by the nurses in preoperative assessment clinic (POA). All patients are given information at this point about their procedure and the anaesthetic so patients can make informed decisions. Posters are also displayed in the POA waiting area so patients are aware of this process.

The pathway is in line with the guidance in the RCOA ‘Guidance of the provision of anaesthetic services [1]’: ‘Following procedures under general anaesthesia, a responsible adult should escort the patient home and provide support for the first 24 hours after surgery. A carer at home may not be essential if there has been good recovery after brief or non-invasive procedures and where any post-operative haemorrhage is likely to be obvious and controllable with simple pressure. Transport home should be by private car or taxi; public transport is not normally appropriate.’ In writing the pathway we took in to account patient’s wishes but also the safety of the procedures. Our surgical exclusions in the pathway are in line with GPAS guidelines. Our main concerns for postoperative complications were haemorrhage and airway compromise, these are not common causes for readmission but they could be catastrophic, therefore we excluded all airway surgery, surgery around the neck and laparoscopic surgery where direct pressure cannot be applied. Also, patients having eye surgery, if partially sighted in their other eye, are not considered to be able to go home on their own for obvious patient safety reasons. On the day of surgery, the responsible surgeon and anaesthetist are able to change the pathway to the inpatient pathway if required.

Patients who prefer to have a carer after surgery but are unable to arrange this will be offered an overnight bed but will be made aware that there may be a risk of cancellation on the day if the beds are not available. Also, as usual, patients are encouraged to find someone to stay with them if they do not fit the criteria for the self-care pathway. All surgeons, anaesthetists and nursing staff were informed of the pathway. We have a lead nurse to help with education and implementation in Day Procedure Unit. Recently we have adopted a ‘self-care pathway’ outcome on the computer system which links with the operating list. It is important to note that patients must still have an escort to take them home. An escort home provides important functions such as helping with information recall, providing observation on the way home and settling the patient in on arrival home. Since introduction the self-care pathway has been successfully implemented. A small survey after introduction showed all patients managed on the self-care pathway were satisfied and no problems have occurred with these patients.

Conclusion

It is clear that there is a wide variation in practice in this area of day surgery, both in terms of what the patients choose to do (despite instructions) and what different departments recommend. Concern regarding impairment of cognitive and psychomotor skills has often been cited as reasons for requiring care following day surgery. In addition, the legal implications of driving after anaesthesia cannot be underestimated as demonstrated in case reports of accidents and subsequent malpractice suits in patients who drove after day surgery [20]. However, it is imperative to make a distinction between the patient driving and the patient having overnight care - these two are clearly not the same and as such should not be grouped together. It remains imperative that patients are escorted home by a responsible adult and seen safely into their home so that someone knows they have had surgery and are home alone, if this is going to be the case.

Day surgery has continually evolved over many years and now encompasses a wide spectrum of procedures and patients. This means that a ‘one size fits all’ approach to certain aspects of the practice of day surgery may not be in the best interests of the patients or departments and hospital trusts. Articles and recommendations have often focussed on the day surgery population as a whole but it is clear that different patient groups are likely to have different requirements post-operatively. This is demonstrated in the survey by Barker et al. where the time it took for patients to feel safe varied depending on the extent of their surgical procedure and expected pain levels. It may therefore be more appropriate to identify different groups of patients depending on the procedures and their wishes. GPAS guidelines for day surgery state ‘A carer at home may not be essential if there has been good recovery after brief or non-invasive procedures and where any post-operative haemorrhage is likely to be obvious and controllable with simple pressure’. This encompasses a large number and variety of day case procedures. This is demonstrated well by the policy at Norfolk and Norwich, where carefully selected patients may be sent home, despite no carer being present overnight.

It should be noted that although we describe the literature on this subject, this is not a formal systematic review or analysis of the evidence and we accept this as a limitation of this article. Similarly, caution must be applied when applying results of international studies and surveys to the UK population and practice due to the clinical heterogeneity as well as differing healthcare structures (e.g. private vs. public funded). A UK based randomised controlled trial in this area may well be indicated.

While the literature is limited, there is no firm evidence of harm when no carer is present. Many patients presenting for day surgery will ‘by default’ have someone available for support at home in the form of a spouse, partner or family member. This support is often invaluable to the patient following their procedure. However, day surgery units should have dynamic policies in place and seek innovative solutions when faced with patients who do not have overnight care. This is reflected in the latest guidelines in the United Kingdom [1, 2].

Acknowledgements

This article is based on two presentations given at the 2017 BADS Annual Scientific Meeting in Southport.

References

- Noble T. A Model for Providing Day Surgery for Patients with No Overnight Care. Journal of One-Day Surgery. 2014. 24S. B1.

- Allan K, Morris R, Lipp A. Day Procedure Survey: Self Care Post Discharge at the Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital (NNUH). Journal of One-Day Surgery. 2015. 25S. A20.

- Royal College of Anaesthetists (RCOA). Guidelines for the Provision of Anaesthesia Services (GPAS). Guidelines on the provision of anaesthesia services for day surgery (2016). https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/GPAS-2016-06-DAYSURGERY.pdf

- Verma R, Alladi R, Jackson I, Johnston I, Kumar C, Page C, Smith I, Stocker M, Tickner C, Williams S and Young R. Day case and short stay surgery: 2, Anaesthesia 2011; 66: pages 417-434

- Discharge Process and Criteria. International Association for Ambulatory Surgery. http://www.iaas-med.com/index.php/iaas-recommendations/discharge-process-and-criteria Accessed 1 March 2017.

- Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists (ANZCA). Guidelines for the Perioperative Care of Patients Selected for Day Stay Procedures (PS15). 2016. http://www.anzca.edu.au/documents/ps15-2010-recommendations-for-the-perioperative-ca.pdf

- Apfelbaum JL, Silverstein JH, Chung FF, Connis RT, Fillmore RB, Hunt SE, Nickinovich DG, Schreiner MS, Silverstein JH, Apfelbaum JL, Barlow JC, Chung FF, Connis RT, Fillmore RB, Hunt SE, Joas TA, Nickinovich DG, Schreiner MS; American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Practice Guidelines for Postanesthetic care. An Updated Report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Postanesthetic Care. Anesthesiology. 2013; 118: 291-307.

- Dobson G,Chong M, Chow L, Flexman A, Kurrek M, Laflamme C, Lagacée A, Stacey S, Thiessen B. Dobson G, Chong M, Chow L, et al. Guidelines to the Practice of Anesthesia – Revised edition 2017. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2017. 64: 65-91.

- Fahy A, Watson BG and Marshall M. Postanaesthetic follow-up by questionnaire: A research tool. British Journal of Anaesthesia. 1969; 41: 439.

- Ogg TW. An assessment of postoperative outpatient cases. British Medical Journal. 1972; 4: 573-576.

- Correa R, Menezes RB, Wong J, Yogendran S, Jenkins K, Chung F. Compliance with postoperative instructions: a telephone survey of 750 day surgery patients. Anaesthesia. 2001; 56: 447-484.

- Cheng CJC, Smith I, Watson BJ. A multicentre telephone survey of compliance with postoperative instructions. Anaesthesia. 2002; 57(8): 805-11.

- Barker J, Holmes K, Montgomery J, Bennun I, Stocker M. How long is 24 hours? A survey of how long a carer stays with the patient post discharge. Journal of One-Day Surgery. 2014. 24(2): 57-60.

- Wessels F, Kerton M, Hopwood H. Evaluating the need for day surgery patients to have 24 hours of adult supervision postoperatively. Journal of One-Day Surgery. 2015. 24(4): 17-2.

- Friedman Z, Chung F, Wong DT. Ambulatory surgery adult patient selection criteria – survey of Canadian anesthesiologists. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2004; 51(5): 437-44.

- Stomberg MW, Brattwall M, Jakobsson JG. Day surgery, variations in routines and practices a questionnaire survey. International Journal of Surgery. 2013; 11(2): 178-82.

- Segerdahl M, Warren-Stomberg M, Rawal N, Brattwall M, Jakobsson J. Clinical practice and routines for day surgery in Sweden: results from a nation-wide survey. Acta Anaesthesiologica Scandinavica. 2008; 52: 117-124.

- Ip HYV, Chung F. Escort accompanying discharge after ambulatory surgery: a necessity or a luxury? Current Opinion in Anesthesiology. 2009. 22: 748-54.

- Abdullah HR, Chung F. Postoperative issues: discharge criteria. Anesthesiology Clinics. 2014; 32: 487-493

- Chung F, Assmann N. Car accidents after ambulatory surgery in patients without an escort. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2008; 106(3): 817-820.

- Chung F,Imasogie N, Ho J, Ning X, Prabhu A, Curti B. Frequency and implications of ambulatory surgery without a patient escort. Canadian Journal of Anesthesia. 2005; 52(10): 1022-1026.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6186/281-retief.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1228#collapse6

Authors

Nweze Uchenna Onochie Senior Registrar

Ebirim Longinus Ndubuisi Consultant

Alagbe-Briggs Olubusola Temitope Consultant

Department of Anaesthesiology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital, Port Harcourt, Nigeria

Correspondence: Dr L N Ebirim, Department of Anaesthesiology, University of Port Harcourt Teaching Hospital. Port Harcourt

Email: longinus.ebirim@uniport.edu.ng Phone: +2348033384198

Keywords: Recovery Anaesthesia, Day case Surgery

Abstract

Background Use of spinal anaesthesia is gaining popularity for day-case gynaecological procedures which are of short duration. However, complications associated with use of lidocaine for spinal anaesthesia made an alternative necessary. This study compared the recovery profile and home readiness of patients using 12.5mg, 10mg, and 7.5mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine for subarachnoid block in day-case gynaecological procedures lasting not more than one hour.

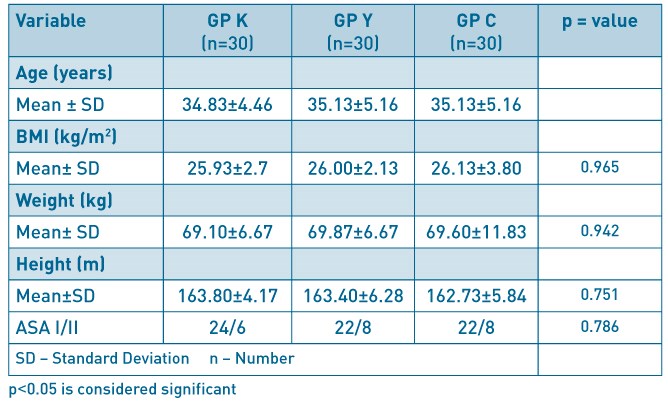

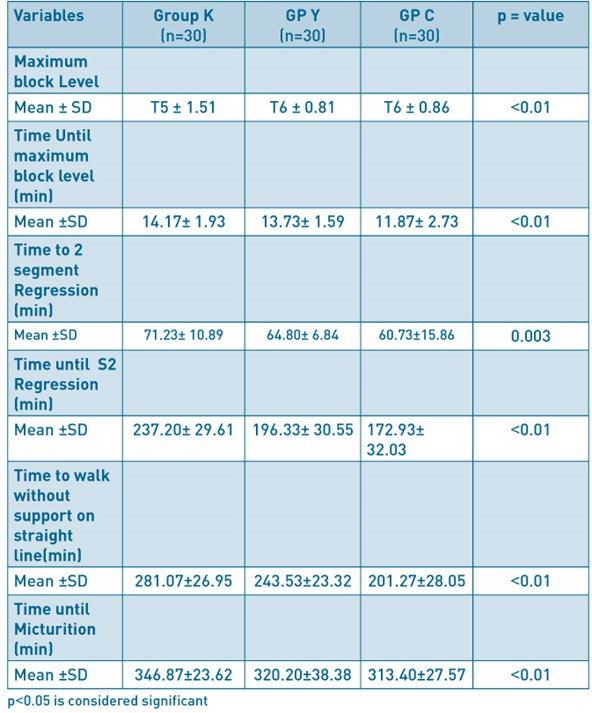

Methods Following ethical committee approval, ninety patients, aged 18–45 years with ASA class I or II scheduled for day case gynaecological procedures, who gave informed consent, were randomly allocated into 3 groups (K, Y or C). They received intrathecally, 2.5ml, 2.0ml and 1.5ml respectively of 0.5% hyperbaric bupivacaine made up to 3mls by adding 0.5ml, 1ml and 1.5ml each of normal saline. Intraoperative and postoperative monitoring till full recovery and discharge was observed. Data were analyzed using SPSS Version 20.

Results The mean of maximum height of block was T5 in group K, and T6 in groups Y and C (p<0.01). The time until two segment regression, time to S2 regression, time to walk without support on a straight line and time to micturition decreased proportionally as the dose of bupivacaine reduced (group K>group Y>group C) ( p <0.01).

Conclusion Recovery and home readiness were significantly faster when 7.5mg of hyperbaric bupivacaine was used for spinal anaesthesia in day-case gynaecological procedures lasting not more than one hour compared to 10mg and 12.5mg doses.

Introduction

Ambulatory surgery is becoming popular in Nigeria because of its advantages to the patient, surgeon and the hospital. It is convenient, cost effective, reduces the demand on limited inpatient facilities and shortens surgical waiting list1.

The ideal anaesthesia for ambulatory procedures should provide a rapid and smooth onset of action, good intraoperative analgesia, good operating condition and short recovery time free from side effect2. Spinal anaesthesia is gaining popularity and acceptance in ambulatory setting because it is easy to administer, avoids airway manipulation, and provides continued post-operative analgesia. However, general anaesthesia with relaxation technique is the most commonly used anaesthesia in Nigeria.3

Recovery profile in spinal anaesthesia is a measure of the continual process of return of normal sensation following subarachnoid block which could be assessed using the following parameters; time to two segment regression of level of block, time to four segment regression of level of block or recovery of sensation to particular landmark segment such as T10,L1 or S2. Home readiness is when patient meets discharge criteria following anaesthesia and is usually determined by the following; ability to walk without support, ability to void, stable vital signs, and lack of side effects.

Most outpatient gynaecologic procedures are usually of short duration and lidocaine which has a short duration of action was widely used for spinal anaesthesia in such procedures4,5. However, lidocaine was associated with postoperative Transient Neurologic Symptoms (TNS) characterized by back pain that radiates to the buttock or lower extremities and this necessitated the need for an alternative6,7.

Other local anaesthetics that have been used for ambulatory procedures include ropivacaine and bupivacaine8. Ropivacaine when compared with bupivacaine has a more rapid regression of sensory and motor block, earlier mobilization and shorter time to micturition9. Ropivacaine is preferred to other long acting local anaesthetics in ambulatory setting, but it is not readily available in our sub region. Bupivacaine is the readily available long acting local anaesthetic often used for spinal anaesthesia in Nigeria. It achieves very reliable block, is considered very safe in experienced hands and duration of action is known to be dose dependent. Low dose of hyperbaric bupivacaine has been used in ambulatory anaesthesia for different procedures with varying results10,11. To produce a reliable spinal anaesthesia with reasonable recovery time, it is essential to choose the optimal drug and adequate dose for specific procedures2.

It was deemed necessary to determine if there would be a significant difference in recovery profile and time of home readiness when different low doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine that could provide adequate duration of intraoperative spinal anaesthesia are used. The purpose of this study was therefore to compare the recovery profile of low doses of hyperbaric bupivacaine in patients undergoing spinal anaesthesia for day-case gynaecological procedures.

Methods