Dave Bunting

Dave Bunting

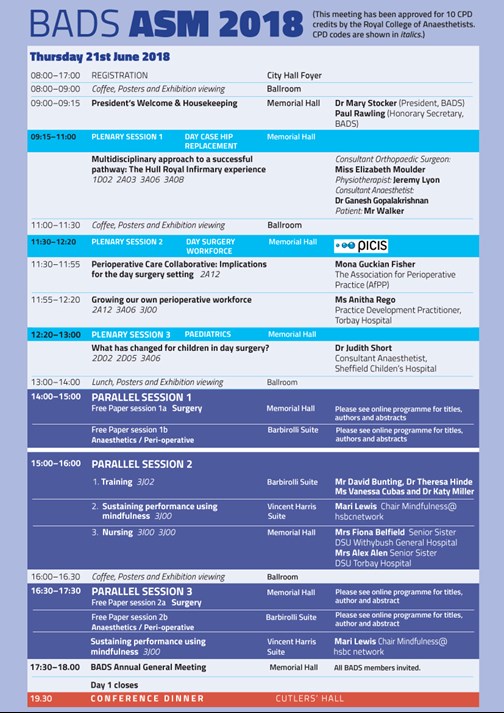

This edition of JODS follows the very successful Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM) held in June at the Sheffield City Hall. As promised all abstracts presented whether in poster or oral format are published in this edition of the Journal and are citable as peer-reviewed abstract publications. Feedback from the meeting was very positive, the overall programme content was rated as good or excellent by 93% attendees, overall timetabling was rated as good/excellent in 95% and the venue was rated as good/excellent in 94%. Preparations are well underway for next year’s ASM, which is to be held at the Royal Society of Medicine in London.

Since introduction of the application and web-based platforms last year, The Journal of One-Day Surgery is continually striving to improve the service it provides to its subscribers, to increase the accessibility of articles and to enhance the functionality of its electronic platforms. This month brings a new and important development whereby individual articles are available to view and download in PDF format, directly from the JODS app and JODS section of the BADS website.

This edition of JODS features full manuscript publications from work presented at the ASM this year. They include an audit of operation note documentation comparing practice with guidelines issued by the Royal College of Surgeons; a report of a single unit’s experience in ureteroscopy and lasertripsy for renal stone management; a service evaluation of major ear surgery performed as a day surgery and a study on the factors associated with successful day case tonsillectomy.

NHS England’s monthly performance statistics have this month shown that the number of patients waiting over a year for planned treatment has reached the highest level in over 6 years. Planning guidance issued by NHS England suggests that the number of patients waiting more than 52 months for treatment should be halved by next year and eliminated where possible, however, it seems unlikely that this will be achievable in many trusts. Maintaining highly productive day-surgery units is vitally important in helping to achieve these targets by reducing elective waiting times, especially as the majority of patients waiting over a year will be suitable for day surgery procedures.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6189/282-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse0

Mary Stocker

Mary Stocker

As I write this we are in the final stages of preparing for what looks to be an excellent conference in Sheffield next week. We are delighted to see that the delegate numbers for the meeting have returned to well over 200 which is very encouraging and a tribute to the conference organising team ably led by Kim Russon and Fiona Belfield.

One of the significant developments in day surgery this year has been the introduction of hip and knee replacement surgery on a day case basis. I am greatly looking forward to hearing from the team from Hull who are presenting their pioneering work developing day surgery total hip replacements. Later in the year (September 20th) BADS are running a joint meeting with Healthcare Conferences dedicated to day surgery arthroplasty. Here we will hear from both the Hull and the Northumberland team about day case total hip replacements and the team in Torbay about their day case uni-chondylar knee replacements. If you are unable to join us in Sheffield do think about coming along to this meeting in London in September.

Another exciting initiative is the work BADS have been doing with the Model Hospital team. We have supported them in developing a day surgery tool for their model hospital data information site. This enables each trust to benchmark their own day surgery rates for all procedures within the BADS Directory of Procedures, you will be able to analyse your own trusts day case rates and unplanned admission rates by individual procedure, by surgical specialty and overall. It also ranks all the trusts nationally for each procedure in terms of day case rates enabling us to identify top performers and hence hopefully learn from areas of best practice. We hope this will be launched within the next few weeks and we will ensure that a link is available for members form our website.

Finally I am delighted to announce that our 30th Annual Scientific Meeting will be held at the Royal Society of Medicine in London on 27th/28th June 2019. Do put it in your diary now! I hope to see many of you next week in Sheffield.

Mary Stocker

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6190/282-pres.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse1

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6198/282-asm.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse2

Authors

Dr Vishramb Mattadeen ITU Registrar, Croydon Health Services.

Tel: 07950423476 Email: vmattadeen@gmail.com

Abstract

Hospital acquired hyponatremia is relatively common, yet probably overlooked in terms of its potential associated complications and mortality. A drop in serum sodium can lead to cerebral oedema as a result of electrolyte-free water moving into the brain cells. The early signs of acute hyponatremia and rising intracranial pressure are often nonspecific and hence often missed.

A 32-year-old female patient underwent an uneventful hysteroscopy for primary infertility and subsequently became drowsy in the recovery area of the day case unit. Investigation revealed a sodium level of 117mmol/L (Serum sodium of 140mmol/L one week prior to procedure). She was monitored in recovery area and soon she developed generalised seizures and got transferred to HDU for observation. Slow sodium correction improved her condition within 18 hours and she went home the next day.

Once back to herself, it was to everyone’s surprise to hear to the following statement: “I was asked to drink a lot of water so that I can pass urine (which was a criterion for discharge from a day care surgery), so I drank around 3 litres of water”.

The National Patient Safety Agency in the UK has identified hospital-acquired hyponatremia in children and adult as a major patient safety issue. Appropriate monitoring and early intervention remains the key to avoid potentially deadly complications.

Introduction

Hospital acquired hyponatremia is relatively common, yet probably overlooked in terms of its potential associated complications and mortality (1). Acute hyponatremia is defined as a decline in serum sodium within a 48-hour period to less than 130 mmol/L. This abrupt change can lead to cerebral oedema as a result of electrolyte-free water moving into the brain cells. Acute hyponatremia can be fatal for both children and adults. The early signs of acute hyponatremia and rising intracranial pressure are often nonspecific and include nausea, vomiting, headache, and decreasing level of consciousness (2,3). I present a witnessed and treated case of acute hyponatraemia in a day case patient to highlight the potentially life-threatening complications associated with acute hyponatremia.

Incident Report

A 32-year-old female patient was admitted for a day case procedure – hysteroscopy for primary infertility. Post an uneventful procedure the patient was transferred to the day surgery recovery where she initially recovered well and started taking orally. The unit waited for her to pass urine and eventually transfer/discharge her. In the meantime, she was encouraged to drink water. She started having headache after 4 hours which persisted and she became drowsy after around 6 hours of the procedure where she was transferred to the main operation theatre recovery. A blood gas revealed a serum sodium of 117 mmol/L for which she was started on normal saline while considering the dose for hypertonic saline. Unfortunately, the patient started having seizures for which she was urgently transferred to ITU/HDU for closer monitoring, while she was on an infusion of normal saline at 100ml/hr. She was post ictal and a repeated sodium showed a level of 121 mmol/L. A decision was taken to continue normal saline infusion and slowly correct the serum sodium level. The patient improved gradually with the level rising to 128 mmol/L after 18 hours. Once back to herself, it was to everyone’s surprise to hear the following statement: “I was asked to drink a lot of water so that I can pass urine (which is a criterion for discharge from a day care surgery, so I drank around 3 jugs of water (3 litres of water)”.

Discussion with surgeons only revealed a short procedure with the use of normal saline solution which is highly unlikely to cause such a severe hyponatremia, which led the team to think that this is a case of polydipsia leading to severe, life threatening hyponatremia.

Article continues after ad.

Background information about Acute Hyponatremia

Hyponatremia can occur if there is a disproportionate loss of sodium such as occurs with primary kidney disease or conditions that affect the ability of the kidneys to conserve sodium. It can also occur because of a disproportionate gain of electrolyte-free water in the vascular compartment, also known as dilutional hyponatremia or water intoxication. The increased ratio of free water to sodium in the vascular space will cause the water to move from this extracellular compartment into the intracellular compartment until osmolality is equalized; free water will enter body cells (i.e., brain cells) and cellular oedema will result.

In acute hyponatremia, the brain cells are unable to compensate for the rapid decrease in serum osmolality; as such, minor increases in electrolyte-free water can lead to disproportionately large increases in intracranial pressure due to swelling of the brain cells. Children exhibit symptoms more quickly than adults in response to abnormal sodium levels because there is less room for the brain cells to swell (the brain reaches its adult size by the time the child is 6 years old, but the skull does not reach adult size until a person is 16 years of age).

Since the early signs and symptoms of acute hyponatremia are often nonspecific, healthcare professionals may attribute them to other causes, such as the postoperative effects of anaesthetics, medications administered for pain, or the presenting illness. A rapid decline in serum levels of sodium leading to symptoms of increased intracranial pressure is a medical emergency, as further increase in brain-cell swelling can cause seizures, respiratory depression, coma, irreversible brain damage, or brain herniation and death.

The kidney is the main regulator of water through the activity of antidiuretic hormone (ADH). ADH (also known as vasopressin) acts directly on the kidneys, causing them to reabsorb water, which helps to maintain the serum sodium, and thus the osmolality of the blood, within normal limits. A reduction in serum osmolality (as occurs with a reduction in serum sodium) typically inhibits the release of ADH, whereas an increase in serum osmolality causes the release of ADH. This “osmotic” feedback system in the body allows for variability in electrolyte-free water intake so that serum osmolality and serum sodium remain within normal range.

ADH is also known to be released in response to numerous “non-osmotic” stimuli, even when serum sodium falls to below-normal values. One of the most potent stimuli for ADH release is nausea and vomiting. Other non-osmotic stimuli for the release of ADH include pain, stress, gastroenteritis, hypoxia, positive pressure ventilation, trauma, and commonly used medications such as opioids. Numerous disease states such as pneumonia are also known to cause the release of ADH. The release of ADH after surgery in response to non-osmotic stimuli typically resolves by the third postoperative day but can last up to the fifth postoperative day. Children appear to be at particular risk after surgical procedures, and deaths have been reported after even minor surgery. Importantly, in the presence of ADH, the kidneys cannot eliminate excess electrolyte-free water. In addition to the administration of hypotonic parenteral solutions such as “2/3 and 1/3”, oral and enteral intake may be a source of electrolyte-free water that contributes to the development of acute hyponatremia (e.g., hypotonic feeds, water, ice chips). Experts have noted that hyponatremia is the most common electrolyte disturbance among children being treated in hospital because such patients are commonly exposed to non-osmotic stimuli for ADH and also because the administration of hypotonic solutions is routine practice in many hospitals. (2-5)

Discussion

Iatrogenic hyponatremia is fairly common. We are possibly more acquainted to hyponatremia in marathon athletes, cyclists which led to hospitalisation and even death as is the case of David Rogers in April 2007. Hyponatremia remains the most common electrolyte disorder which results in brainstem malfunction (1).

The National Patient Safety Agency in the United Kingdom has identified hospital-acquired hyponatremia in children and adults (to a lesser extent) as a major patient safety issue. Safety alerts and guidelines for the administration of fluids to children, in particular, have been published as a result. Canadian Medical Protective Association and the US institute for Safe Medical Practice have also raised their concerns followed by recommendations (4).

There appears to be a general consensus that isotonic fluids such as normal saline/sodium lactate should be used during surgery, and in the treatment of moderate to severe hypovolemia; however, there is debate as to which solution is the best choice for maintenance of hydration. Experts are questioning the widespread use of hypotonic solutions for parenteral maintenance, a practice based on a formula that was developed more than 50 years ago. The formula is derived from minimum free-water requirements based on caloric expenditure per kilogram of body weight. Experts argue that this formula overestimates maintenance requirements for a variety of reasons; most importantly, the formula presumes normal excretion of free water by the kidneys and thus does not take into account ADH released in response to non-osmotic stimuli, a process that was identified since the original development of the formula and that is commonly seen in hospitalized children. In one recent study, a key factor in the development of hospital-acquired hyponatremia was the use of hypotonic maintenance solutions. A variety of studies, including randomized trials, are answering questions about the use of maintenance fluids in patients. Experts do agree, however, that there is no single IV solution that is ideal for all patients (6).

Parenteral fluids administered for the purpose of hydration have not traditionally been viewed with the same rigour as medications. These fluids are usually distributed through a central supply and redistribution service or through hospital stores as part of the materials management division of hospital operations.

Recommendations and Considerations

There are currently no guidelines telling about the amount of water or fluids to be taken orally post a day case surgery as it all depends on the patient’s age, weight, intravascular volume status, comorbidities and fluid loss in a surgery. Therefore, it should be based on clinical judgement.

Ensure that guidelines for fluid and electrolyte therapy are aligned with the regional institutions/trusts within the area and that these guidelines include:

- the optimal choices for parenteral solutions and rates of administration;

- the circumstances under which hypotonic solutions may be used;

- the minimum requirements and frequency for:

- monitoring serum electrolytes,

- accurate measurement of all sources of intake and output (during every shift, and with an ongoing

cumulative balance);

- early involvement of the most responsible physician in cases where fluid intake greatly exceeds urine output;

- how to identify, treat, and monitor patients with electrolyte disorders such as hyponatremia (e.g., specify when additional monitoring such as measurement of urine osmolarity and urine electrolytes are required);

- criteria for expert consultation.

Engage family members whenever they express concerns about their relatives’ behaviour. Subtle changes may be more readily identified as abnormal by family members than by healthcare providers and thus can provide an invaluable source of assessment information.

References

- Progress hearing in the matter of: Hyponatraemia-Related Deaths; held at the Hilton Hotel on Friday 30th May 2008, Belfast (Ireland): Inquiry into Hyponatraemia Related Deaths [cited 2009 Aug 29]: 1-5.

- Ball S, Barth J, Levy M; Society for Endocrinology Clinical Committee. SOCIETY FOR ENDOCRINOLOGY ENDOCRINE EMERGENCY GUIDANCE: Emergency management of severe symptomatic hyponatraemia in adult patients. Endocr Connect 2016; 5(5) G4-G6.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, et al. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatraemia: Expert Panel Recommendations. Am J Med 2013 126(10 Suppl 1): S1-2.

- The Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP) Canada Safety Bulletin; Hospital-Acquired Acute Hyponatremia: Two Reports of Pediatric Deaths; October 27, 2009, Volume 9, Number 7: 1-4.

- Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B et al. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. European Journal of Endocrinology, 1 March 2014, 170 (3) G1-G47.

- Shafiee MA, Bohn D, Hoorn EJ, Halperin ML. How to select optimal maintenance intravenous fluid therapy. Am J Med. 2003;96(8):601-610.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6197/282-mattadeen.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse3

Authors

Dr. David MacDonald Foundation Year 2 Doctor, Great Western Hospital – Surgical Department

Email: david.macdonald2@nhs.net

Mr. Steven Lindley General Surgical Registrar, Great Western Hospital – Surgical Department

Email: stevenlindley@nhs.net

Keywords: Surgical Ward Round; Operation note; Efficiency.

Abstract

Introduction: Finding a specific item in a patients’ medical records often requires patience. Searching for an operation note can be frustrating and time consuming. Colour-coded paper has long been used for handwritten proformas, but typed documents are often printed on plain white paper.

The hypothesis that colour-coded operation notes help identification and reduce the time to locate was explored to justify the money spent on paper bearing a pre-printed coloured edge.

Methods: Thirty health care professionals participated. Two sets of notes; 15cm and 2cm deep, each had a typed operation note with a coloured edge and one without, inserted, at random, into the notes. Health care professionals were timed to find each operation note in both set of notes.

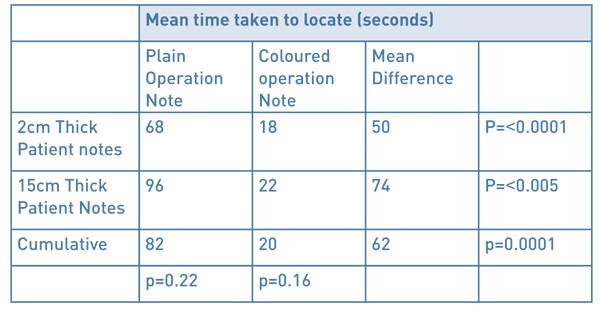

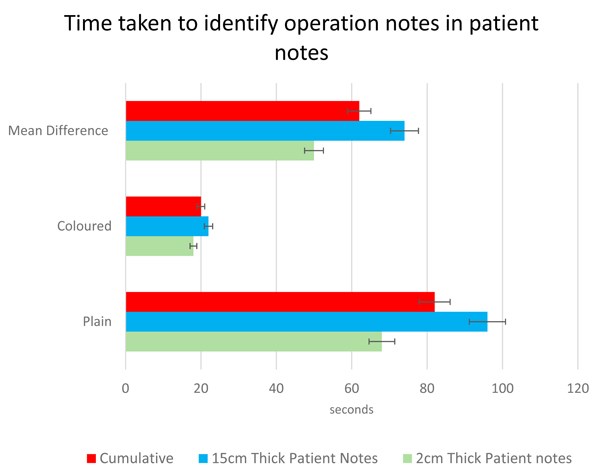

Results: When comparing the 60 plain notes with the 60 coloured edge notes, a paired T-test revealed statistical significance (p=0.0001). The mean time to find the plain note was 82 seconds, and the note with the coloured edge 20 seconds. The mean difference was 62 seconds.

A paired T-test revealed that there was no statistical difference between the size of the notes when comparing the times to find plane or note paper with the coloured edge.

Conclusion: Identifiable paper saves time when searching through a set of notes. This intervention saves over 1-minute searching for specific items in the notes. This has a real, yet small impact on the efficiency of all healthcare professionals looking after the patient. Although marginal, the potential cumulative gains to patient safety should not be overlooked.

Introduction

The Royal College of Surgeons (RCS) published the Good surgical Practice Guidelines in 2008. These detailed the minimum information required of a surgical operation note, to enable continuity of care by another doctor (1). Legible and accurate documentation has been correlated with improved clinical care (2), facilitates audit and research and provides an important role in medico-legal conflicts (3). Consequently, the RCS guidelines were updated in 2014 to include that operation notes should be preferably typed for every procedure. It has been subsequently evidenced that an electronic operation note proforma markedly improves the quality of documentation (4,5).

Although written operation notes were traditionally printed on colour-edged paper, since the introduction of the electronic operation note, notes are often printed on plain white paper. The increased pressures on healthcare professionals are well documented, and locating a single document within patients’ notes is known to be a laborious and frustrating task.

We hypothesised that using a colour coded operation note with a red stripe down the right-hand side, would decrease time spent locating the operation note, and therefore improve communication and efficiency within the surgical team.

Method

A total of 30 health care professionals from Great Western Hospital NHS Foundation Trust participated. A plain white operation note was randomly included within a set of patient notes, and the participant was timed whilst they found it. The authors felt that random placement reflected common practice, or at least, a predictable position in the notes was not recognised as being reliable in our experience. This process was then repeated using an operation note with a red stripe down the right hand side. This experiment was performed using two sets of patient notes: one 2cm deep and another 15cm deep, to simulate patients with different volume of hospital records, reflecting the average patient.

Statistical Analysis:

Timings were compared using the same participants to find coloured and plain operation notes in each set of notes. Parametric data was analysed using paired Students’ T Test. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

Article continues after ad.

Results

Times taken to find 60 plain operation notes were compared to the times taken to find 60 coloured edge notes. In the 2cm patient notes the mean time taken was 68 seconds for the plain notes versus 18 seconds with the coloured operation note (p=<0.0001) with a mean difference of 50 seconds. In the 15cm patient notes, it took a mean time of 96 seconds for plain notes compared with 22 seconds finding the coloured operation note (p=<0.005), with a mean difference of 74 seconds. Amalgamating the data across patient notes of different sizes, the mean time taken to locate the plain operation note was 82 seconds, and the coloured operation notes 20 seconds (p=0.0001, 95% CI 38.6 – 85.2). There was no statistical difference in the time taken to identify either operation note based purely on the size of the patient notes, plain (p=0.2154) and coloured (p=0.1595).

Table 1: Comparison between times taken to locate plain and colour-edged operation notes in

2 different sizes of patients’ records.

Figure 1: Comparison between times taken to locate plain and colour-edged operation notes

in 2 different sizes of patients’ records. Confidence intervals shown as whiskers.

Discussion

The operation note is an important document, frequently reviewed by many members of the multidisciplinary team. Improvements to Patient Administration Systems (PAS software) has allowed for a growing trend in the creation electronic operation notes. Until hospitals move over to being fully electronic, there is a need for contemporaneous operation notes to be printed and easily accessible in hard-copy form in the notes. With increasing demands on the NHS and the inpatient teams, the requirement for an efficient ward round has never been more important. A simple amendment to the electronic typed operation note, of a red stripe down the right-hand side, resulted in an average of over a minute less spent to identifying it in a set of patient notes. This efficiency is also appreciated by busy allied health professionals when accessing operation notes.

The authors acknowledge that ‘standardised note organisation’ has been a recognised standard agreed by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges since 2008 (6). The AOMRC do not elaborate as to what taxonomy this standardisation should apply; on the same ward, across an NHS trust, NHS wide? The experience of the authors and the wider surgical team is that note standardisation differs between wards and hospitals. Where standardisation is recognised, the reliability of this is often poor (loose papers put in the front of the notes/ notes filed in chronological order for that admission/notes placed in correct speciality). As a result, our experience is that ‘no system’ is followed when looking for the operation note in the patients record, and thus, our methodology reflects wider practice. We accept that in a well organised institution where there is reliable note organisation, those members of staff whom recognise the standardised organisation, the benefit of colour coded notes on speed of localisation will be less significant. For patients who have had multiple operations, there will be an additional task of reading the date/time/title, in order to sort to the note you require. For many institutions, the accessible notes are the ‘acute’ records, and therefore multiple operation notes in these records will be a relatively rare finding. In this scenario, while it is likely that all of these operation notes are useful to locate quickly and read, the benefit of colour coded notes on efficiently finding the most recent note will be reduced.

Although these efficiency savings are modest, the accumulated effect on efficiency, productivity and therefore patient safety, should not be overlooked.

References

- The Royal College of Surgeons of England. RCSENG - Professional Standards and Regulation; 2014. Good Surgical Practice. https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/gsp/domain-1/1-3-record-your-work-clearly-accurately-and-legibly/

- Lyons, T.F. and Payne, B.C. The relationship of physicians' medical recording performance to their medical care performance. Care. 1974; 12: 714–720

- Gomey, M. Accurate medical records your primary line of defence. Health Care Risk Rep. 1998; 10: 1

- Coughlan F, Ellanti P, Moriarty A, McAuley N, Hogan N. Improving the Standard of Orthopaedic Operation Documentation Using Typed Proforma Operation Notes: A Completed Audit Loop. 2017 Mar 7;9(3):e1084. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1084

- Int J Surg. 2014;12(5):30-2. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2013.10.017. Epub 2013 Nov 14. 'Smart' electronic operation notes in surgery: an innovative way to improve patient care. Ghani Y1, Thakrar R, Kosuge D, Bates P.

- Academy of Medical Royal Colleges A Clinician’s Guide to Record Standards – Part 2: Standards for the structure and content of medical records and communications when patients are admitted to hospital 2008. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/sites/default/files/FPM-clinicians-guide2.pdf

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6196/282-macdonald.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse4

Authors

Kelly-Anne Ide Specialty Doctor, North Devon District Hospital

David L Sanders Consultant Upper GI Surgeon, North Devon District Hospital

David M Bunting Consultant Upper GI Surgeon, North Devon District Hospital

Corresponding author

Kelly-Anne Ide 31 Aspen Grove, Fremington, Barnstaple EX31 3FB

Email: kide@nhs.net

Keywords: Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy; Emergency Cholecystectomy; Day Case Cholecystectomy.

Abstract

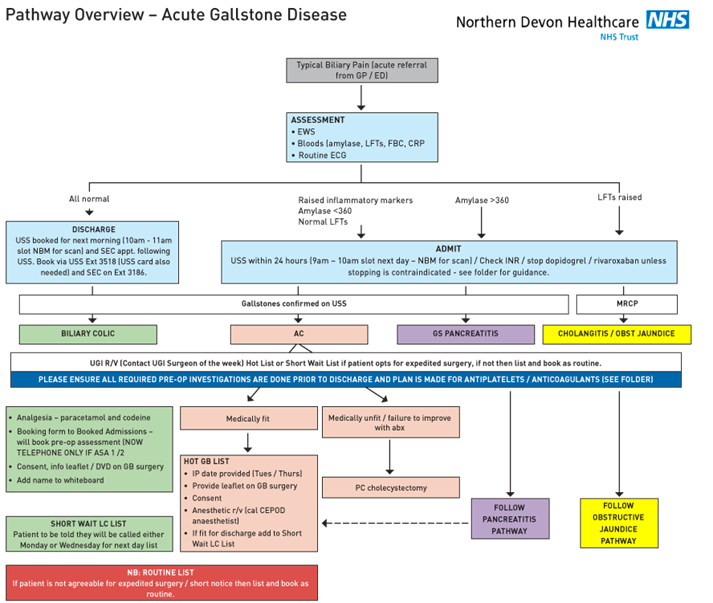

Introduction: The treatment of gallstones disease is evolving, with an emphasis on early cholecystectomy following index admission with biliary problems. This report outlines our experience in implementing a pathway for day case emergency cholecystectomies.

Methods: A pathway for people with symptomatic gallstone disease was designed, and two theatre lists per week were allocated to “hot cholecystectomies”. Patients are discharged if well enough and brought back for a day case procedure, with the aim of 80% undergoing surgery within 14 days of admission.

Results: 170 patients underwent emergency cholecystectomy between January 2017 and March 2018. Over this period 80% of patients had their surgery within 14 days, ranging from 54% to 100% on a monthly average. Mean time from emergency admission to surgery was 7 days. 71% were discharged and brought back for surgery. 46.5% overall were discharged on the same day as surgery. Readmission rate was 5.3%.

Conclusion: Early cholecystectomy is a recommended treatment for acute gallstone disease, and our experience demonstrates that it is possible to perform this on a day case basis in the majority of suitable patients.

Introduction

The treatment of acute gallstone disease has evolved in recent years with an emphasis on early surgery to improve outcomes. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellent (NICE) currently recommend performing cholecystectomy within one week of diagnosis of acute cholecystitis1 and the British Society of Gastroenterologists recommend surgery on index admission for gallstone pancreatitis, or within 2 weeks if this is not possible2. This has been shown to result in lower morbidity, shorter length of stay and duration of antibiotics, as well as reduced costs, with no associated increase in complications3-5.

The Royal College of Surgeons launched a pilot project (CholeQuIC)6 in January 2017 to investigate the feasibility of implementing this as a national standard. This article describes our experience of this process and outlines our results.

Methods

Upon enrolling in the CholeQuIC project we began by designing a pathway for the diagnosis and management of gallstone disease (see Figure 1). Patients were deemed eligible for hot cholecystectomy if they had acute cholecystitis, gallstone pancreatitis or biliary colic severe enough to require admission and were medically fit for surgery. Those with non-resolving obstructive jaundice were included once they had undergone endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP). There was much debate among the sites involved as to an achievable target timeframe for surgery. The CholeQuIC aim was for 80% of patients to undergo surgery within 8 days of admission. We felt this was not realistic for our site and set our own target of 80% within 14 days of admission.

Figure 1: Biliary Pathway.

Operating lists

Two theatre lists per week were allocated to “hot cholecystectomies” which gave us capacity for four cases per week. The four operating consultants rotate on a weekly basis. Lists took place in the mornings, in an emergency general surgery theatre. These theatre sessions were created in addition to pre-existing, emergency capacity and, therefore, time was, protected for “hot cholecystectomy” use except in the event of a life-threatening emergency. This negated the issue of placing cholecystectomies on the emergency operating list and being cancelled for more urgent procedures, as is a common problem in many institutions.

Patient Pathway

Initially cases were all performed on an inpatient basis during their index admission. It quickly became obvious, however, that some of these patients were well enough to be discharged whilst waiting for their surgery. We therefore altered our pathway to create a day case emergency cholecystectomy system. The patients have all their required pre-operative investigations performed whilst they are an inpatient (electrocardiogram (ECG), blood group and save, HbA1C) and have a pre-operative assessment booked before they leave. If they are American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade 1 or 2 they are able to have this assessment by telephone. In most cases they are given a date for surgery before they are discharged, however, some patients required a further assessment by an anaesthetist in which case their name was recorded on a white board and they are listed once deemed fit to go ahead. On the day of surgery, patients present to the day surgery unit, are booked in and undergo surgery that morning. Discharge on the same day as surgery is the default pathway in all eligible patients. Patients not eligible for day case surgery are identified at the time of booking onto the waiting list or at pre-operative assessment and are admitted to the ward post-operatively. Such patients include those without a suitable carer available in the post-operative period and those with significant medical co-morbidity (e.g. ASA 3) requiring overnight monitoring of observations.

Results

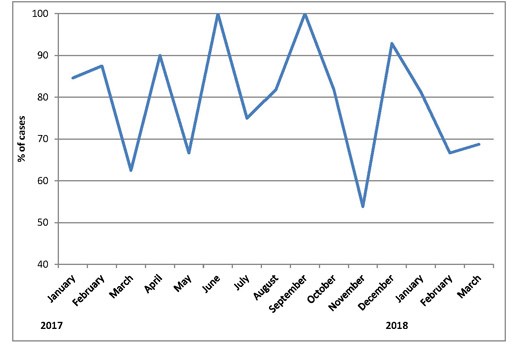

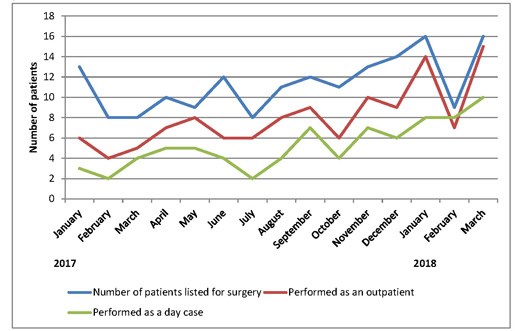

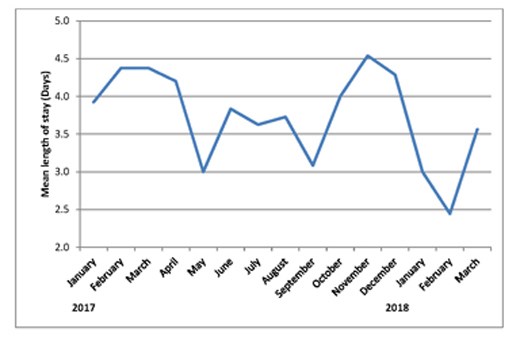

Between January 2017 and March 2018, we have performed 170 emergency cholecystectomies. The breakdown of diagnosis is shown in Table 1. Between 8 and 20 patients were enrolled onto the pathway each month. Three lists were cancelled during this period – two for emergency laparotomies and one for an organ harvest. Overall 136/170 (80%) of patients had their operation within 14 days of emergency admission, with the monthly rate varying from 54% to 100%, see Figure 2). Average (mean) time from emergency admission to surgery was 11.4 days (range 1-191 days). After initial admission, 71% patients were discharged and brought back for day case surgery. The remainder had surgery as inpatients. 46.5% patients overall were discharged on the day of surgery (see Figure 3). The day case rate was higher in the patients who had been discharged prior to surgery compared to the inpatient group (63% vs 8%, P<0.0001, Fisher’s exact test). Average (median) length of stay on the index admission was 3 days (range 0-19 days) see Figure 4.

At a mean follow up of 216 days (range 6-463 days), nine patients (5.3%) were re-admitted post-operatively with complications. Two had common bile duct stones and required ERCP; two developed wound problems requiring inpatient assessment/treatment; one developed a bile leak and required re-operation-, one patient developed gastroenteritis post-operatively and one had possible pancreatitis but with normal liver function tests so no imaging was undertaken. The final two were readmitted with post-operative pain but no cause was found. Seven (4.1%) cases were converted to an open procedure.

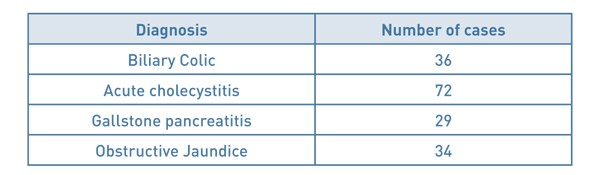

Table 1: Breakdown of cases by diagnosis.

Figure 2: % of cases performed within 14 days of admission.

Figure 3: Run chart showing number of cases performed as an outpatient

and number of day case procedures.

Figure 4: Average length of stay on index admission by month.

Discussion

Implementing this change has been challenging, however, we achieved our target rate of 80% of patients having cholecystectomy within 14 days of admission. Our conversion and readmission rates are consistent with those published in the literature7-10 and the proportion performed on an outpatient, day case basis are increasing month on month. Patients undergoing surgery as an inpatient are less likely to have a day case procedure, which is expected in a group who are more unwell with higher pre-operative pain levels. Our aims for the future are to maintain these standards and continue to increase our day case rates in a bid to help reduce the financial burden of an increasingly common condition.

References

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2014) Gallstone disease: diagnosis and management. NICE guideline (CG188).

- UK Working Party on Acute Pancreatitis. UK guidelines for the management of acute pancreatitis. Gut 2005; 54: iii1-iii9.

- Roulin D, Saadi A, Di Mare L, Demartines N, Halkic N. Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis, Are the 72 hours Still the Rule?: A Randomized Trial. Ann Surg 2016; 264(5): 717-722.

- Gutt CN, Encke J, Köninger J, Harnoss JC, Weigand K, Kipfmüller K, Schunter O, Götze T, Golling MT, Menges M, Klar E, Feilhauer K, Zoller WG, Ridwelski K, Ackmann S, Baron A, Schön MR, Seitz HK, Daniel D, Stremmel W, Büchler MW. Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicentre randomized trial (ACDC study). Ann Surg 2013; 258(3): 385-393.

- Song G, Bian W, Zeng X, Zhou J, Luo Y, Tian X. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: early or delayed? Medicine 2016; 95(23): e3835.

- Royal College of Surgeons. Cholecystectomy Quality Improvement Collaborative (CholeQuIC) [Online: Cited 23rd April 2018] Available at: https://www.rcseng.ac.uk/standards-and-research/standards-and-guidance/service-standards/emergency-surgery/cholecystectomy-quality-improvement-collaborative/

- Sakpal SV, Bindra SS, Chamberlain RS. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Conversion Rates Two Decades Later. JSLS 2010; 14(4): 476-483.

- Lau H, Brooks DC. Contemporary Outcomes of Ambulatory Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy in a Major Teaching Hospital. World J Surg 2002; 26(9): 1117-1121.

- Harboe KM, Bardram L. The quality of cholecystectomy in Denmark: outcome and risk factors for 20,307 patients from the national database. Surg Endosc 2011; 25(5): 1630-1641.

- Ballal M, David G, Wilmott S, Corless DJ, Deakin M, Slavin JP. Conversion after laparoscopic cholecystectomy in England. Surg Endosc 2009; 23(10): 2338-2344.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6195/282-ide.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse6

The Journal of One-day Surgery considers all articles of relevance to day and short stay surgery. Articles may be in the form of original research, review papers, audits, service improvement reports, case reports, case series, practice development and letters to the editor. Research projects must clearly state that ethics committee approval was sought where appropriate and that patients gave their consent to be included. Patients must not be identifiable unless their written consent has been obtained. If your work was conducted in the UK and you are unsure as to whether it is considered as research requiring approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), please consult the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool at http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Articles should be prepared as Microsoft Word documents with double line spacing and wide margins. Submissions must be sent by email to the address below. A scanned letter requesting publication signed on behalf of all authors must also accompany articles.

Any source of funding should be declared and authors should also disclose any possible conflict of interest that might be relevant to their article.

Title Page

The first page should list all authors (including their first names), their job titles, the hospital(s) or unit(s) from where the work originates and should give a current contact address for the corresponding author.

The author should provide three or four keywords describing their article, which should be as informative as possible.

Abstract

An abstract of 250 words maximum summarising the manuscript should be provided and structured as follows: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions.

Main article structure

Manuscripts should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and References. Tables and figures should follow, with each on a separate page. Each table and figure should be accompanied by a legend that should be sufficiently informative as to allow it to be interpreted without reference to the main text.

All figures and graphs are reformatted to the standard style of the journal. If a manuscript includes such submission, particularly if exported from a spreadsheet (for example Microsoft Excel), a copy of the original data (or numbers) would assist the editorial process.

Copies of original photographs, as a JPEG or TIFF file, should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedding pictures within the text of the manuscript.

Figures and Graphs

Where possible, we will use the figures and graphs you provide in the manuscript. This ensures that the data you provide is that which is used. Figures and graphs can be presented in colour BUT try to avoid 3-d effects, shading etc. Figures and graphs may be redrawn if the quality is not in keeping with the Journal. Please provide these at the end of your Word document BUT make it obvious where you would like these placed in the finished article (ie in the main text, type ‘Figure 1 near here’ or Table 1 near here’)

Photographs

Photographs can be provided as jpg or tiff files but should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedded within the text of the manuscript. This ensures higher quality images. However, we will accept images within Word documents but image quality might suffer!

References

References should be cited numerically in the order in which they appear in the text. References should list all authors' names. Please provide both the first and last page numbers.

Authors. Article title. Journal title (in italics) Year of publication;Volume:page range.

Example reference

Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281.

Submissions are subject to peer review. Proofs will not normally be sent to authors and reprints are not available.

All items should be emailed to The Editor:

Email Address for submissions: davidbunting@nhs.net

Mr David Bunting Editor, Journal of One Day Surgery, Consultant Upper GI Surgeon, North Devon District Hospital

[These guidelines were last revised on 11.03.2018]

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1263#collapse7