Dave Bunting

Dave Bunting

This edition of JODS brings you a detailed report of the Annual Scientific Meeting (ASM) held in June at the Sheffield City Hall. The meeting was a great success attracting many more delegates than in recent years and with generally very positive feedback. I would like to thank all those delegates who provided online feedback from the conference. As always BADS are always looking to improve the experience offered at our annual signature event and as we plan for and look forward to next year’s 30th Annual Conference, we have taken on board feedback regarding timing of sessions and sizing of rooms. In many ways the parallel sessions were victims of their own success with standing room only at the back for some of the most popular sessions. Our chosen venue for the ASM next year, the Royal Society of Medicine in London promises a fantastic conference experience and I am sure it will attract a large number of high-quality scientific abstracts in addition to an impressive line-up of invited speakers.

I hope that JODS readers have been able to enjoy being able to download articles in PDF format, directly from the JODS app and JODS section of the BADS website. Please explore this functionality in this edition of the Journal if you have not already.

This edition’s scientific articles include an audit of complications from intrathecal pumps used in the treatment of spasticity; a pre-operative testing quality improvement write-up; a report from the introduction of a day-case uterine fibroid embolization pathway; an audit into complications of laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery; a service improvement project in theatre utilisation/efficiency; an audit of readmissions and complications following cholecystectomy and a case series review of green light XPS prostatectomy.

The announcement earlier this month from the Chancellor of the Exchequer that the NHS is to receive an increase in its budget of £7.2 billion is welcome news indeed, however, we will need to wait before understanding the impact this will have on day case surgery.

The Royal College of Surgeons of England has urged NHS England to reconsider its inclusion of operations for common hand conditions in the list of clinically ineffective operations. If commissioning guidance were to go ahead as planned, patient access to treatments for carpel tunnel syndrome, Dupuytren’s contracture, trigger finger and wrist ganglion would be withdrawn or severely restricted.

Finally, it is with great sadness that we report the passing of Dr Peter Simpson, one of the founding members of our Society 1989 and his obituary is included in this edition of the Journal.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6043/284-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse0

Mary Stocker

Mary Stocker

As only two months have passed since my last letter you might think that there would be little to report, however I am pleased to say that BADS Council are still beavering away and there are various new initiatives on the horizon.

However firstly, I am sad to report the recent death of one of our founding members and past presidents Dr Peter Simpson and am very grateful to Ian Jackson for his obituary which appears in this issue and for the huge contribution Peter made over many years to BADS. May he rest in Peace.

Peter worked tirelessly for our Association over many years and I think it is fitting as he was one of the pioneers of day surgery benchmarking that I can report two current initiatives which council are involved with around day surgery benchmarking. The first is the long awaited Model Hospital reporting tool which I am assured is now imminently to launch the day surgery compartment, benchmarking all hospitals within England for all procedures within the BADS Directory. The second refers to the National Getting it Right First Time Programme (GIRFT). This is an initiative being led by NHS England and rolled out across a variety of specialties. We are engaging with the teams to try to ensure that Day Surgery activity is a core component of all surgical GIRFT Programmes and those anaesthetists among you who have already had their GIRFT visit will know that day surgery activity is a large component of the anaesthetic GIRFT programme. Hopefully this will continue to drive day surgery performance across the country as it becomes a key component of this important benchmarking activity.

Council are continuing to look at opportunities for developing a day surgery accreditation programme. Jo Marsdon is leading this for us and I am delighted that she has made significant inroads with the Royal College of Anaesthetists accreditation programme and other accreditation organisations such that we are beginning to progress this key aspect of our work.

Following the interest sparked at our last conference about day surgery joint replacements we organised a sell out one day meeting in collaboration with Healthcare Conferences in September. There were some inspirational presentations from the teams from Northumberland and Hull which left us all feeling “why not”? We are hoping to run a second event in the spring. Watch this space. For those of you North of the Border, myself and Jo Marsden will be visiting the Grampian and Tayside Health boards to support the launch of their day surgery programmes later this month and we hope to plan a one day day surgery conference in Edinburgh in the spring – there is certainly a real desire for change in Scotland and its quite exciting watching your programmes develop.

As I write this it is bonfire night and I can hear the fireworks across the bay of Torbay, this will therefore be my last letter of 2018 so I wish you a Holy Advent, Happy Christmas and very successful 2019!

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6044/284-pres.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse1

Authors

R. D. Wells, A. K.Allouni & S. Merron

Authors' Addresses

Wells R.D. Consultant Interventional Radiologist. Lead and corresponding author, UHNM NHS Trust, Royal Stoke University Hospital, Newcastle Road, Stoke-on-Trent ST4 6QG

Keywords

Day case, UFE, Fibroid embolisation, fibroids, radial access.

Abstract

Setting up a day case Uterine Fibroid Embolisation (UFE) service has been a challenge for Interventional Radiologists for many years. There is a body of opinion that the immediate post-procedural phase is just too painful to treat these patients on an ambulatory care basis. However, in a healthcare system under the strain of in-patient bed shortages our unit decided to review practice and find ways of delivering effective therapy to patients in more efficient ways. Clinicians believed that the service could be successfully delivered with patients going home on the same day as the embolisation. We worked with patients, anaesthetists, gynaecologists, day case and surgical assessment units to produce a practical, pragmatic approach to provide women with the option of a day case procedure. In this article we describe in detail the evolution of this successful service and the rationale for each component in the pathway.

Introduction

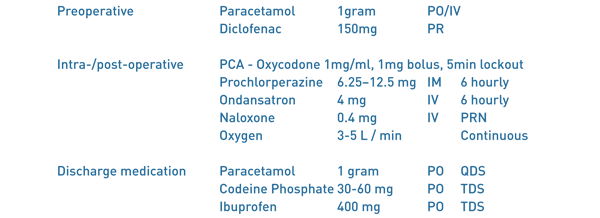

Prior to 2017 our strategy for managing patient’s ischaemic pain from embolising the uterine arteries relied on preoperative anti-inflammatory medications and Patient Controlled Anaesthesia (PCA) during the procedure and overnight stay. (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Pre-2017 analgesia protocol.

In our experience, although the PCA provided adequate pain relief in the majority of patients, a significant number had a poor experience due opioid related nausea and constipation. Indeed, these were their main complaints when seen in follow up. We also noticed that there could be significant delays in patients being discharged following an overnight stay. This tended to be due to a combination of logistical and human factors; including the PCA not being taken down in time, take home medications not being processed and nurse understaffing.

Methods

In 2017, we reviewed the then current day case analgesia practices for patients undergoing gynaecological day case surgery, including laparoscopic myomectomy. Much of this concentrated on the conduct of the anaesthetic and care given within the post-operative recovery area. We also researched other strategies employed in the management of acute peri-operative pain. For example the use of gabapentinoids within the acute pain setting. Given preoperatively this class of drugs can also provide anxiolysis for patients. There is also good evidence that gabapentinoids significantly reduce opioid consumption in the post-operative period (1,2,3)

Collaborating with an anaesthetic consultant who has a special interest in interventional radiology (4) we produced a comprehensive analgesic regime which relies heavily on preventing the ischaemic pain experienced by some women. Senior nursing staff in the interventional radiology unit, the radiology day case unit (RDCU) and Surgical Assessment Unit (SAU) were all involved in creating a patient pathway that was geared to discharging the patient on the same day, but with provision for an overnight bed for failed day case discharges. The surgical day case unit (DCU) has an overnight stay facility and, at least in the first few cases, this was booked as a fall back, but was never utilised. It was also necessary to offer a safety net for those patients who had been successfully discharged on the day of the procedure. If a patient either, required advice, or to needed to return to hospital, then it was agreed that this would be facilitated by direct access to the nursing staff on the SAU. The literature suggests an expected readmission rate of at most 10% (5, 6).

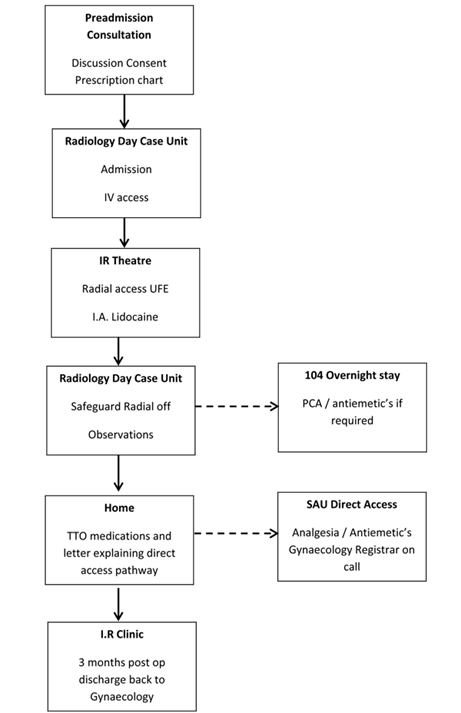

The prospect of a successful day case scenario truly emerged however, with adoption of the trans-radial (TR) arterial approach. Compared with a traditional trans-femoral (TF) approach, TR access dramatically reduces the risk of significant access site haemorrhages and allows patients to mobilise immediately (7). Closure of the radial arteriotomy is achieved using a variable compression wrist device. Once this radial band is removed, on average 40 minutes, and the discharge protocol parameters met, the patient can be safely discharged. The only issue to manage then was pain. The full day case pathway is summarised in (Fig. 2).

Figure 2 Patient pathway.

Pre-admission

Patients are referred by local gynaecologists having been diagnosed with symptomatic uterine fibroids, usually on ultrasound and clinical grounds. Most patients have not responded to or declined medical therapy. Every patient undergoes an MRI examination to characterise the size and location of the fibroids and any associated disease process such as adenomyosis. We then invite patients to a pre-assessment joint clinic run by an interventional radiologist and a specialist nurse. This affords the opportunity to council the patient on UFE, review the imaging, and allows time to go through a rigorous consent process. At this point it is often clear if patients are motivated by the prospect of a day case procedure and their pathway can be planned accordingly. All patients have routine blood tests within 30 days of the procedure; including coagulation profile, Full blood count, renal function and CRP. Pregnancy screening is completed on the day of admission.

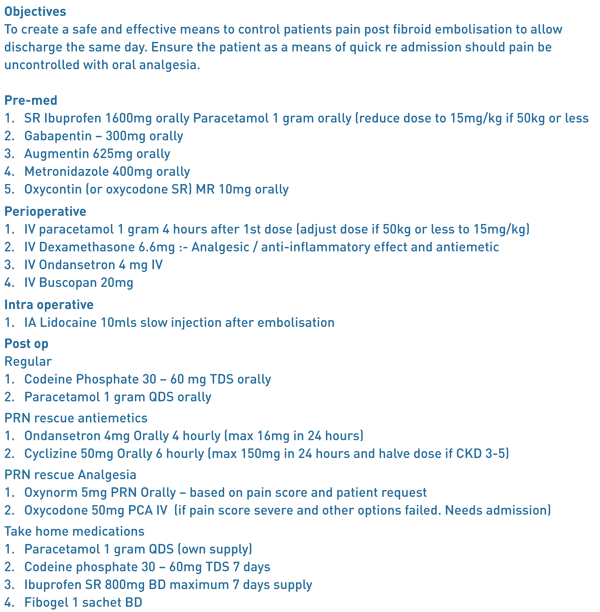

Day case medications: rationale and mechanism of action

Figure 3 Post-2017 day case protocol.

Preoperative Medication

Ibuprofen SR 1600mg orally: Ibuprofen is a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). NSAIDs inhibit the action of the cyclooxygenase enzymes. This leads to a reduction the production of inflammatory and pain causing prostaglandins.

Gabapentin 300mg orally: Gabapentin is a gabapentinoid drug with an onset of action within 30-90 minutes after oral dosing. It activates the inhibitory Gaba-ergic receptors associated with the central NMDA receptors. It can exert anxiolytic and sedative effectives and also alters the transmission of nociception at a spinal cord level. It has been well established that gabapentinoids work synergistically with opioids and reduce overall opioid requirements. Gabapentinoids not only improve the quality of analgesia, but reduce the incidence of post-operative nausea and vomiting, by reducing opioid consumption (1,2,3). In trials, patient satisfaction with postoperative pain management was significantly higher at 24 hours following pre- and postoperative oral gabapentin compared with placebo (p<0.001) (2). However we decided that, due its sedative action, gabapentin would not be routinely used postoperatively. Similarly, we do not give intraoperative midazolam.

Oxycodone SR 10mg orally: Oxycodone is a euphoric opioid analgesic with approximately 1.5 times the efficacy of comparable morphine doses. Onset is within 30 minutes with a duration of between 4 and 6 hours.

Perioperative Medication

Paracetamol 1 gram IV: (if >50 kg otherwise 15mg/kg): The mechanism of action of paracetamol is still poorly understood. It is generally accepted that it acts on multiple levels in the pain pathways, having effects on prostaglandin inhibition, the serotonin pathway and endocannabinoid enhancement. The introduction of IV paracetamol has made the bioavailability much more predictable with a speed of onset of 5 minutes and duration of 4-5 hrs. (8,9).

Dexamethasone 6.6mg IV: This is a potent synthetic corticosteroid . It has been shown to have both analgesic and anti-inflammatory effects . It has a strong anti-emetic effect , especially when used in conjunction with other more conventional antiemetic’s (10, 11).

Ondansatron 4mg IV : This medication has powerful antiemetic properties. It exerts these through competitive antagonism of the 5-HT3 receptors within the brain.

Intraoperative Medication

Lidocaine 5ml 1% IA : into both uterine arteries . This was shown to significantly reduce the pain scores at 4 hrs and reduce the opioid requirement by up to 50% (12).

Postoperative Medication

Paracetamol 1 gram PO: Regularly. Four times daily.

Codeine Phosphate 30-60mg PO: Regularly. Three times daily.

Ondansatron 4mg IV : As required.

Oxynorm 5mg PO: As required rescue analgesia. Based on pain score.

Oxycodone 50mg PCA IV: As required rescue analgesia. If pain score is severe and other options failed. This necessitates an admission.

Discharge Medication

Paracetamol 1 gram PO: Regularly. Four times daily. 7 day supply.

Codeine Phosphate 30-60mg PO: Regularly. Three times daily. 7 day supply.

Ibuprofen SR 800mg PO: Twice daily. 7 day supply.

Fibogel 1 sachet PO: Twice daily. 2 sachets.

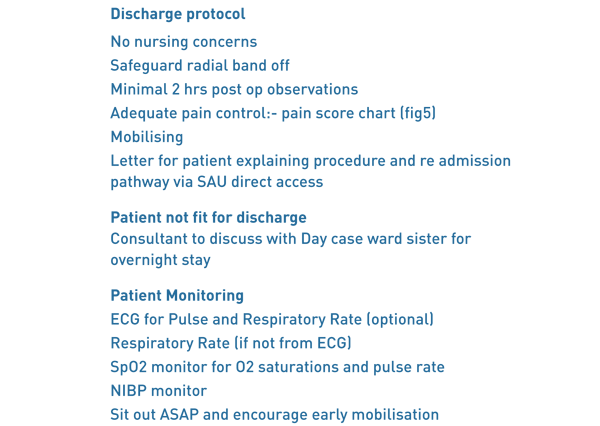

Discharge protocol

For patients to be safely discharged home they require transport and an adult present in their home overnight.

Figure 4.

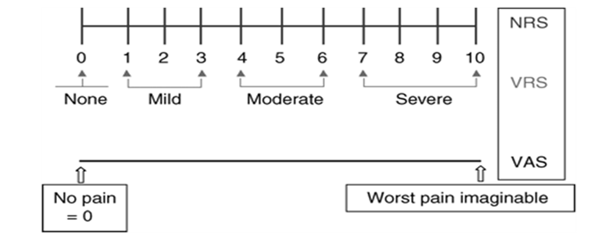

On the ward the radial arteriotomy site is checked. There is a minimum of two hours stable blood pressure, pulse and oxygen saturations. The patient’s pain score is assessed and documented (Fig. 5).

If the pain score is less than 6 and patient is able to cope then the patient is given their take home medications and a letter for direct access back to the surgical assessment unit.

Fig 5 Pain score chart.

Follow up

Following discharge, a specialist nurse conducts a telephone consultation with the patient within the following week to assess for any short term complications such as on-going pain, signs of infection or heavy discharge. Patients then return 3 months post procedure for a consultation with an interventional radiologist to assess the symptomatic outcome of the procedure. At this point, re-intervention may be discussed, often with a follow-up MRI.

Early Results

Of the first ten patients following this protocol, 9 patients were discharged before 8pm and had no complications or complaints at the 48-hour, nurse led telephone follow up. One patient progressed to an overnight stay, however, this was no due to pain or complications, but simply she had failed to disclose a lack of somebody at home to care for her in the overnight postoperative period; a fundamental criteria for day case admission. This patient did not require a PCA and was discharged home the following morning. There were no readmissions via the surgical assessment (SAU) rapid access protocol for pain or infection. Of the cases that have returned for 3 months clinic follow-up, all have been technically successful with significant improvement in symptoms. The mean screening time was 14min 65sec with a mean dose (DAP) of 549.05 mGy/cm2 .

Discussion

Day case procedures have become the mainstay of a modern NHS practice. With advances in techniques, especially radial artery access UFE, the support of a working group and increased demand from patients we have developed an evidenced based structure to deliver this patient orientated pathway in IR.

To set up a practice like this takes a coordinated approach from a preadmission IR nursing team that informs and involves the patient before the procedural day. To ensure enough recovery time, the procedure needs to first on the list in the morning and the clinicians have to promptly prescribe the preoperative medication. Ensuring the perioperative and intraoperative medication is given in a timely manner prevents the build-up pain. The pathway is followed through to the post op care, discharge and finally follow-up.

We have a strict discharge protocol (Fig. 4), if the pain score (Fig. 5) is above 6 with all the medication given, then the patient is assessed for overnight stay or even a traditional PCA. Once the patient has been discharged they are given a letter for rapid access back through the SAU to be seen by the gynaecology registrar on call.

Day case UFE lends itself well to radial access. In our institution the radial procedure has proven to be quicker with less radiation dose and the patient is free to mobilise to the bathroom, sit out or lie more comfortably in the bed than common femoral groin access. There is also no risk of a retroperitoneal haematoma and no use of a closure device.

Conclusion

Using a collaborative, evidence based approach, tailored to the specific needs of patients undergoing UFE we were able to formulate a safe, effective and validated strategy for a day case procedure. We do expect some patients to be re admitted for pain control. This should not be seen as a failure of day case, rather a safety net for some patients

References

- Effects of Gabapentin on postoperative morphine consumption and pain after abdominal hysterectomy : A randomised double blind trial. Dierking G, Duedahl TH, Rasmussen ML, Fomsgaard JS, Møiniche S, Rømsing J, Dahl JB Acta anaesthesiologica Scandinavica 2004;48(3):322-7.

- Gabapentin: An alternative to the cyclooxygenase-2inhibitors for perioperative pain management. Turan A, White PF, Karamanlioglu B, Memis D, Tasdogan M, Pamukçu Z, Yavuz E. Anaesthesia and analgesia 2006;102(1):175-81

- Efficacy of pregabalin in acute postoperative pain: a meta-analysis. Zhang J, Ho KY, Wang Y. Br J Anaesthesia. 2011 Apr;106(4):454-62.

- The Royal College of Radiologists. Sedation, analgesia and anaesthesia in the radiology department, second edition. Ref BFCR (18)2

- Tolerance, Hospital Stay, and Recovery after Uterine Artery Embolization for Fibroids: The Ontario Uterine Fibroid Embolization Trial. Pron, Gaylene et al. Journal of Vascular and Interventional Radiology, Volume 14, Issue 10, 1243–1250

- Outpatient uterine artery embolization for symptomatic uterine fibroids: experience in 49 patients. Siskin GP, Stainken BF, Dowling K, Meo P, Ahn J, Dolen EG. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2000;11:305–311.

- Transradial versus transfemoral approach for diagnostic coronary angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention in people with coronary artery disease. Kolkailah AA1, Alreshq RS, Muhammed AM, Zahran ME, Anas El-Wegoud M, Nabhan AF. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018 Apr 18;4:CD012318. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012318.pub2

- What anaesthesiologists should know about paracetamol (acetaminophen), Minerva Anestesiol , Mattia C, Coluzzi F. 2009, vol. 75 pg. 644-53

- Intravenous acetaminophen: a review of pharmacoeconomic science for perioperative use, Am J Ther , 2Jahr JS, Filocamo P, Singh S. 2013, vol. 20 pg. 189-99

- Impact of perioperative dexamethasone on postoperative analgesia and side-effects: systematic review and meta-analysis N. H. Waldron C. A. Jones T. J. Gan T. K. Allen A. S. Habib BJA: British Journal of Anaesthesia, Volume 110, Issue 2, 1 February 2013, Pages 191-200

- The cellular mechanisms of the antiemetic action of dexamethasone and related glucocorticoids against vomiting. Eur J Pharmacol. 2014 Jan 5;722:48-54. Chu CC1, Hsing CH2, Shieh JP3, Chien CC4, Ho CM5, Wang JJ6.

- Intra-arterial Lidocaine for Pain Control in Uterine Artery Embolization: A Prospective, Randomized Study. Noel-Lamy M1, Tan KT2, Simons ME2, Sniderman KW2, Mironov O2, Rajan DK2. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2017 Jan;28(1):16-22.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6045/284-wells.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse2

Authors

Mr Thomas Collins Specialist Registrar, Trauma & Orthopaedics, Royal Bolton Hospital.

tomcollins761@gmail.com

Miss Elizabeth Pinder Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Ipswich Hospital.

epinder@doctors.org.uk

Miss Laura Brennan (Medical Student, Norwich Medical School)|

l.j.brennan94@gmail.com . Mobile Number: 07870669549

Miss Claire Edwards Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

CLAIRE.EDWARDS@nnuh.nhs.uk

Keywords: Efficiency, operating times, day case, theatre optimisation.

Abstract

Introduction Increasing patient numbers causes greater need for theatre efficiency. This paper aims to assess the accuracy of predicted operation times and list finish times within a day surgery unit, implement changes to improve these accuracies and re-evaluate the accuracies.

Method Anaesthetic start, surgical start and finish and list finish times compiled from a computer-based surgical scheduling and resource management software called ORSOS during two 4-month periods. Electronic clinic letters provided predicted surgical times.

Results 82 patients included in initial data collection. 51.9% of lists ended within 30 minutes of the scheduled finish. 64.4% of operations had a predicted time within 20 minutes. 34.2% finished >20 minutes earlier. 1.4% finished >20 minutes later. Average discrepancy of predicted surgical time was a 17.1-minute over-estimation. Average anaesthetic time was 21 minutes. Therefore, average anaesthetic time was added to predicted procedure time and predicted surgical times were reduced 10 minutes. 86 patients included in repeat data collection. 52.4% of lists ended within 30 minutes of the scheduled finish. 43.2% of operations had a predicted time within 20 minutes. 44.6% finished >20 minutes earlier. 12.2% finished >20 minutes later. Chi-square analysis of list finish times between data collections yielded a p-value>0.05.

Discussion Repeat data collection showed accuracy of list finish times had no statistically significant improvement, individual procedures were over- and under-estimated more evenly, as were list finish times, possibly due to variation in case complexity between lists.

Conclusion Consider anaesthetic times individually. Appropriate case mixes scheduled from longest to shortest should be implemented.

Background

Over the past decade there has been a 40% increase in the number of procedures performed within the NHS (1). Optimising theatre lists is, therefore, of great importance with regards to reducing patient waiting times for elective procedures, improving the patient journey and maximising Trust resources.

Theatre efficiency is influenced by numerous factors, many of which have had improvements described in the literature through a variety of methods. For example, employing specific case scheduling policies (2) with the aim of minimising over- and underutilised theatre time, the use of electronic displays with evidence based recommendations (3) to aid decision making with list planning, employing an operating room (OR) manager or OR charter (4) to reduce first case start tardiness, planning anaesthetic assignments and OR choice prior to the list (5) and implementation of structured interventions(6) immediately prior to starting the list to reduce patient turnaround time.

The common denominator that these interventions rely on to be effective is accurate estimation of operating time. The purpose of this study is to determine if improving estimation of operating time can increase theatre efficiency through improved operation scheduling and optimisation of total list time. Our objectives are 1) assess the accuracy of predicted individual operation times and operating list finish times within the hand surgery day case unit at Norfolk and Norwich Hospital, 2) implement changes to improve accuracy of predicted individual operation times and list finish times, 3) evaluate if our changes have improved accuracy of predicted individual operation times and operating list finish times.

Methods

Anaesthetic start times, surgical start and finish times and operating list finish times were compiled from a computer-based surgical scheduling and resource management software called ORSOS for all elective hand lists at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital. Our initial data collection took place between 13th October 2013 – 31st January 2014 and repeat data collection between 6th November 2014 – 27th February 2015. Predicted individual operative times were acquired from dictated clinic letters by surgeons estimating the surgical time following review of each patient. These predicted times were used to plan lists for all surgeons. Clinic letters were stored electronically on a theatre management system called BluespierTMS. The accuracies of predicted individual operation times were calculated by subtracting predicted operation time from actual operation time. “Operation time” was defined as surgical start time to surgical finish time. The list start time was taken as when the first case was sent for (complied from ORSOS). The finish time of each list was taken as the surgical finish time of the final case. This data was audited against the following standards that we felt represented a good level of accuracy 1.) >80% of operating lists finishing within 30 minutes of the scheduled finish time and 2.) >80% of individual operations having an actual operation time within 20 minutes of the predicted operation time. Anaesthetic time was calculated by subtracting the anaesthetic start time from the surgical start time.

Results I

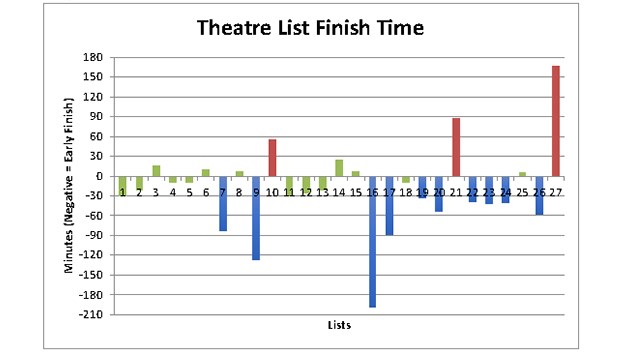

82 patients had operations on 27 operating lists. 51% were female. The age range was 11 – 85 years. The mean early list finish time was 50.1 minutes. This was calculated by averaging all the lists with a negative value shown in graph 1 and table 1. The mean late list finish time was 41.8 minutes. This was calculated by averaging all the lists with a positive value shown in Graph 1 and Table 1.

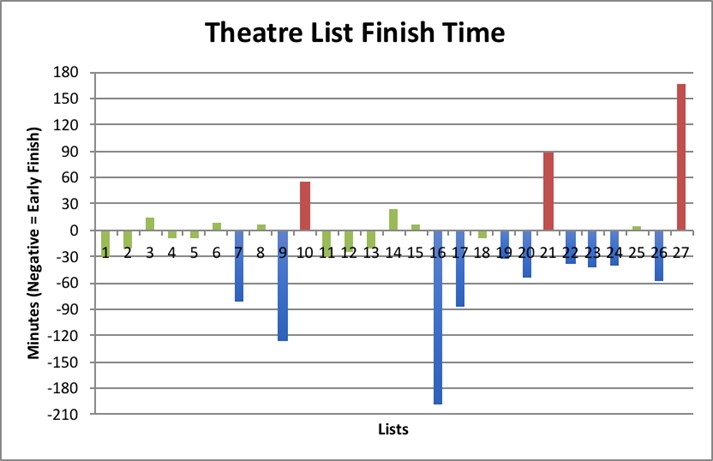

Graph 1: Individual list finish times

Graph 1 shows the number of minutes each list finished earlier or later than the scheduled finish time. The individual bars represent the number of minutes each list finished early or late. Bars that are negative on the y-axis denote lists that finished early, positive bars denote late finishes. Green bars indicate the lists that finished on time, blue bars represent early finishes and red bars denote late finishes (as described in table 2). The numbers along the x-axis correspond to a list number with the date specified in table 1 along with the numerical value of the bars.

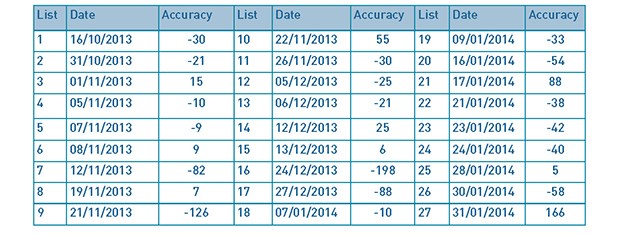

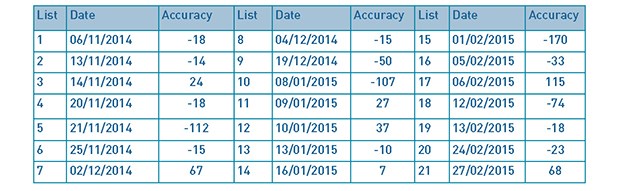

Table 1: List dates and finishing time accuracy.

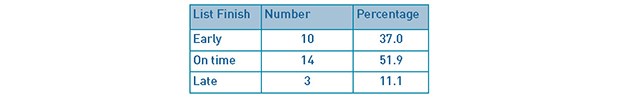

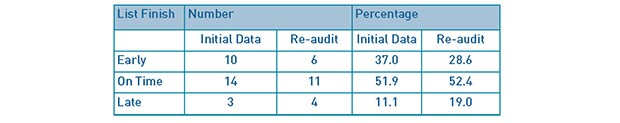

With regards to our first standard, the percentage of operating lists finishing within 30 minutes of the scheduled finish times was 51.9% (as shown in Table 2). This falls below our standard of 80%.

Table 2: List finishing time outcomes.

Table 2 summarises the number and percentage of the 27 theatre lists that finished early, on time or late (between October 13th 2013 – January 31st 2014). Early, on time and late finishes were any list with any accuracy of <-30, -30 - 30 and >30 minutes from the target finish time respectively.

Predicted individual operation times were documented in all but 9 of the 82 cases. Of the remaining 73 cases, 47 had a predicted individual operation time within 20 minutes of the actual procedure time (64.4%) as described in our second standard. 25 cases (34.2%) finished more than 20 minutes earlier than predicted and 1 case (1.4%) finished more than 20 minutes later than predicted. These results are shown in Tables 3 and 4.

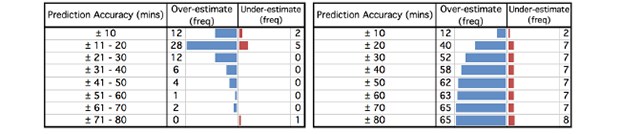

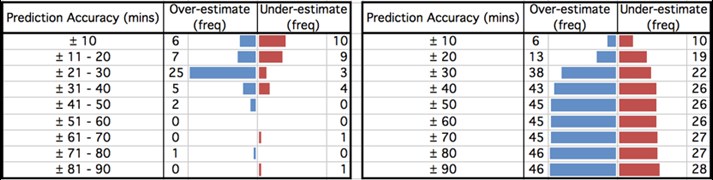

Tables 3 and 4: Accuracy of predicted procedure times for individual cases

Table 3 [left] shows the frequency of cases that either finished earlier (over-estimated) or later (under-estimated) than the predicted operation time. The cases have been split into +/- 10 minute intervals. Table 4 [right] shows the cumulative frequency of all 73 cases with a predicted operation time across increasing +/- 10 minute intervals. The results can be visualised in the funnel plots accompanying each table.

Anaesthetic times were calculated for all but 3 of the 82 cases. Analysis of this data revealed an average anaesthetic time of 21 minutes.

Our results show that for individual operations there is a tendency to over-estimate the predicted individual operation time. This can clearly be seen by the significant skew of the funnel plot in table 4. The average discrepancy in predicted individual surgical time for the 73 cases was an over-estimation (early finish) of 17.1 minutes.

Following analysis of our initial data collection, there were two changes to our operating list planning strategy that we decided to implement in order to improve accuracy of predicted individual operation time, which in theory would lead to improvement in operation list finish times and optimisation of total list time. Firstly, “operation time” was re-defined to include the average anaesthetic time of 21 minutes (calculated from our initial data collection) in addition to surgical time. Secondly, having regularly over-estimated surgical time for all but 8 of the 73 cases (averaging 17.1 minutes), we reduced our predicted individual surgical times by 10 minutes per case. Therefore, with the combination of these two changes we felt an addition of 10 minutes to the predicted individual operation time for each case was a more appropriate way of planning our operating lists to improve efficiency.

Results II

Within the repeat data collection 86 patients had operations on 21 lists. 54.7% were female. The age range was 12 – 87 years. Graph 2 and table 5 show the number of minutes early or late each list finished in relation to the target finish time (described in our first standard). The mean early list finish time was 48.4 minutes, while the mean late list finish time was 49.3 minutes.

Graph 2: Theatre list finish times in minutes.

Graph 2 shows the number of minutes each list finished earlier or later than the scheduled finish time in the repeat data collection. The individual bars represent the number of minutes each list finished early or late. Bars that are negative on the y-axis denote lists that finished early, positive bars denote late finishes. Green bars indicate the list finished on time, blue bars represent early finishes and red bars denote late finishes. The numbers along the x-axis correspond to a list number with the date specified in Table 5 along with the numerical value of the bars

Table 5: List dates and finishing time accuracy.

Table 6; Comparison of list finishing time outcomes.

Table 6 compares the initial audit and re-audit with regards to the number and percentage of the theatre lists that finished early, on time or late. There were 27 lists in the initial audit and 21 in the re-audit (from 6th November 2014 to 27th February 2015).

Predicted individual operation times were recorded for all but 12 of the 86 cases. Tables 7 and 8 show that from the remaining 74 cases, 32 had a predicted individual operation time within 20 minutes of the actual individual operation time (43.2%). 33 cases (44.6%) finished more than 20 minutes earlier than predicted and 9 cases (12.2%) finished more than 20 minutes later than predicted.

Tables 7 and 8: Accuracy of predicted individual operation times for repeat data collection.

Table 7 [left] shows the frequency of cases that either finished earlier (over-estimated) or later (under-estimated) than the predicted operation time. The cases have been split into +/- 10 minute intervals. Table 8 [right] shows the cumulative frequency of all 74 cases with a predicted operation time across increasing +/- 10 minute intervals. The results can be visualised in the funnel plots accompanying each table.

The results from our repeat data collection show that there is a much more even distribution between over- and under-estimated individual operation times, as can be visualised in Table 8. This is reflected in the decrease in average discrepancy of predicted individual operation time from 17.1 to 8.1 minutes over-estimation (early finish).

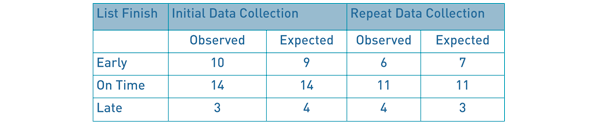

Table 6 shows the percentage of theatre lists finishing within 30 minutes of the target finish improved from 51.9% to 52.4%, remaining below our standard of 80%. A chi-square (Χ2) test assessing the difference in operation list finish times was performed with a null hypothesis (H0) of no difference in accuracy of operating list finish times between list planning strategies. This showed a Χ2(2) = 0.84 (see Table 9), with a corresponding p-value of 0.5<p<0.75. We set α<0.05, yielding a critical value (CRIT) of 5.99 (see Table 10). Χ2<CRIT, therefore, there is no statistically significant difference in the theatre list finishing times between the initial and repeat data collections. We must therefore accept our H0.

Table 9: Observed and expected values of operating list finish times.

Table 9: Observed and expected values of operating list finish times. The expected values shown were calculated by multiplying the row and column totals of the observed values and dividing by the number of lists assessed across both data collections (48). Χ2 was then calculated using the formula Χ2 = Σ(Observed – Expected)2/Expected, to give 0.84 (2 decimal place). The p-value was then calculated at 2 degrees of freedom from a Χ2 distribution table (table 10) to be 0.5<p-value<0.75, and therefore not statistically significant.

Table 10: Chi-square Distributions.

Discussion

Theatre list finish times within 30 minutes of the scheduled finish time did not improve statistically, as shown by our Χ2 test. The mean early list finish time improved from 50.1 minutes to 48.4 minutes, however, the mean late list finish increased from 41.8 minutes to 49.3 minutes. Predicted individual operation times accurate to within 20 minutes of the actual operation time dropped from 64.4% to 43.2%. Predicted individual operation times over-estimated by more than 20 minutes increased from 34.2% to 44.6%, while predicted individual operation times under-estimated by more than 20 minutes also increased from 1.4% to 12.2%. The average anaesthetic time reduced from 21.0 minutes to 18.5 minutes, as did the average predicted operation accuracy from 17.1 to 8.1 minutes over-estimated.

Anaesthetic time was not incorporated within predicted individual operation time for our initial data collection because patients had differing co-morbidities that may have led to a different type of anaesthetic dependant on the anaesthetist covering each operating list. However, following our initial data collection it was clear from the number of over-estimated individual operation times that anaesthetic time needed to be included. The inclusion of anaesthetic time to the predicted individual operation time has had a noticeable effect on the percentage of cases that finish within 20 minutes of their predicted operation time. This is understandable considering the anaesthetic time varied greatly between simple and more complex surgeries, ranging from 0 to 84 minutes in our repeat data collection. Interestingly, the number of individual operations that were over- and under-estimated was much more evenly distributed in our repeat data collection (46 cases over-estimated, 28 cases under-estimated [see table 8]) compared with the initial data collection (65 cases over-estimated, 8 cases under-estimated [see table 4]). The percentage of lists finishing early dropped from 37.0% to 28.6%, while the percentage of lists finishing late increased from 11.0% to 19.1% [see table 6]. Again, this demonstrates that operating list finish times have become more evenly distributed between “early”, “on time” and “late” finishes. Both data collections showed that individual operation times were more likely to be over- rather than under-estimated, although, as previously mentioned this was much less pronounced in the repeat data collection. This may reflect the potential complexity of some cases requiring a more generous estimate. Alternatively, there may have been a requirement for intra-operative decision-making regarding the actual operation performed. Different surgical options will vary in predicted operative time; therefore, when planning operative lists, the longest estimation is most practical.

The greatest scope for improvement in our study is from more accurate planning of the anaesthetic time and appropriate case scheduling. Our allocated anaesthetic time was calculated by taking an average of all the individual cases from our initial data collection. However, a study by Dexter et al(5) described how the most effective means to minimise over- and underutilised theatre time is to liaise with the anaesthetic team. Naturally cases need to be booked onto a list months in advance, but discussing the list with the anaesthetic team within 2 days of the list allowed for any practical issues to be addressed, thereby reducing over-utilised theatre time.

Case scheduling plays an important role in maximising theatre time, especially when cancellations and rescheduling is performed within days of the operative list(7). Cognitive biases, such as risk adverse behaviour, are common amongst those who plan operative lists and has been shown to increase over-utilised theatre time(8). Current evidence shows that the best scheduling policy for reducing over-utilised time is where cases are scheduled from longest to shortest(2), in comparison our lists often had longer cases in the middle or at the end of the list.

There are some limitations to this study. Firstly, the causes for completing an operation earlier or later than expected were not identified and it is possible that unavoidable events may have occurred which could skew the results. We did not assess case mix and variations in complexity between the initial and repeat data collections. Shorter operations are more likely to finish within 20 minutes of their predicted operative time, therefore, a favourable case mix increases the possibility of achieving our standards. First surgeon grade for each case was not assessed either and it is reasonable to assume, for example, that a Consultant may perform certain procedures in a shorter time than a Registrar. Difference in operative time between surgeon grades would also be affected by the complexity of the procedure. For example, a greater difference in surgical time would likely be observed in complex cases as opposed to simple cases. On reflection, measuring surgical times for individual surgeons and operations would be the best way of accurately predicting surgical time.

Conclusions

Using standard surgical times to estimate operation time provides a good foundation for list planning, however, our study has shown that to optimise theatre time the anaesthetic time needs to be considered. This is challenging and ideally should be done on an individual basis with anaesthetic colleagues, but when achieved improved theatre efficiency can be seen through reduction of underutilised theatre time in our repeat data collection. Further studies looking into the variables affecting anaesthetic time, such as type of anaesthetic and patient co-morbidities, may be beneficial in creating a more accurate predicted anaesthetic time to use when list planning. Analysis of surgical times for individual surgeons and operations would be the best way of accurately predicting surgical time.

We recognise that when creating a list some flexibility is required, particularly for complex cases in which time pressures of a potentially overbooked list can be detrimental. However, estimating surgical times based on individual surgeons and specific operations, scheduling cases in descending time order and an appropriate case mix may hold the key to further reducing over- and underutilised theatre time, thereby improving theatre efficiency. The conclusions from this paper may help to inform future studies looking at strategies to optimise theatre utilisation. Further research into these strategies is required.

References

- Secondary Care Analysis Team, NHS Digital. Hospital Admitted Patient Care Activity, 2015-16 [Internet]. 2016 Nov. Available from: https://digital.nhs.uk/catalogue/PUB22378

- Shi P, Dexter F, Epstein RHM. Comparing Policies for Case Scheduling Within 1 Day of Surgery by Markov Chain Models. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2016 Feb;122(2):526–38.

- Dexter F, Willemsen-Dunlap AC, Lee JD. Operating Room Managerial Decision-Making on the Day of Surgery With and Without Computer Recommendations and Status Displays. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2007 Aug;105(2):419–29.

- Ernst C, Szczesny A, Soderstrom N, Siegmund F, Schleppers A. Success of Commonly Used Operating Room Management Tools in Reducing Tardiness of First Case of the Day Starts: Evidence from German Hospitals. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2012 Sep;115(3):671–7.

- Dexter F, Shi PB, Epstein RHM. Descriptive Study of Case Scheduling and Cancellations Within 1 Week of the Day of Surgery. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2012 Nov;115(5):1188–95.

- Soliman BAB, Stanton R, Sowter S, Rozen WM, Shahbaz S. Improving operating theatre efficiency: an intervention to significantly reduce changeover time. Journal of Surgery. 2013 Aug;83(7–8):545–8.

- Dexter F, Maxbauer T, Stout CM, Archbold LB, Epstein RHM. Relative Influence on Total Cancelled Operating Room Time from Patients Who Are Inpatients or Outpatients Preoperatively. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2014 May;118(5):1072–80.

- Stepaniak PS, Mannaerts GHH, de Quelerij M, de Vries G. The Effect of the Operating Room Coordinator’s Risk Appreciation on Operating Room Efficiency. Anesthesia & Analgesia. 2009 Apr;108(4):1249–56.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6046/284-collins.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse3

The Council of BADS are sad to report the passing of Dr Peter Simpson on 19th August 2018. Peter was one of the founding Council Members of BADS in 1989 and was President between 1998-2000. He trained and then taught at St Thomas’ and Northwick Park Hospitals, London 1966-78 being Lecturer in Community Medicine 1974-5. He then joined the Department of Health as a Chief Medical Officer 1978-1988. He then moved to become Regional Medical Officer at Mersey Regional Health Authority. It was during his time there that he helped form BADS – his experience and contacts proving indispensable to the Council.

He was a great leader and had a jolly nature and infectious smile that won many people over to his way of thinking. During his Presidency he championed the development of benchmarking with John Smith of CHKS and Professor Roger Dyson from Keele University – recognised pioneers in this field. This led to the first national benchmarking survey that day units could sign up for and receive feedback on their performance.

Those of us who had the pleasure of working with Peter learned a lot as he was always willing to help with advice. We will miss his infectious smile and laughter.

Ian Jackson

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6047/284-obit.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse4

Authors

Mehdi Raza Surgical Registrar, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust

Aaron Kler Foundation Year Doctor, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust

Ahmed Hamouda Upper GI Consultant, Maidstone and Tunbridge Wells NHS Trust

Correspondence author

Mehdi Raza Surgical Consultant, Darent Valley Hospital, Darenth Wood Road, Dartford, Kent A2 8DA

Email: mehdiraza@nhs.net

Keywords: Laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery, transabdominal preperitoneal (TAPP) and totally extraperitoneal (TEP) repair, post-operative urinary retention (POUR).

Abstract

Introduction: Day care laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery is now more commonly performed than a few years ago. Failure to safely discharge individuals the same day leads to pressure on hospital bed occupancy and adversely affects patient’s experience. This audit looks at the areas where we can potentially improve the patient journey through day case surgery.

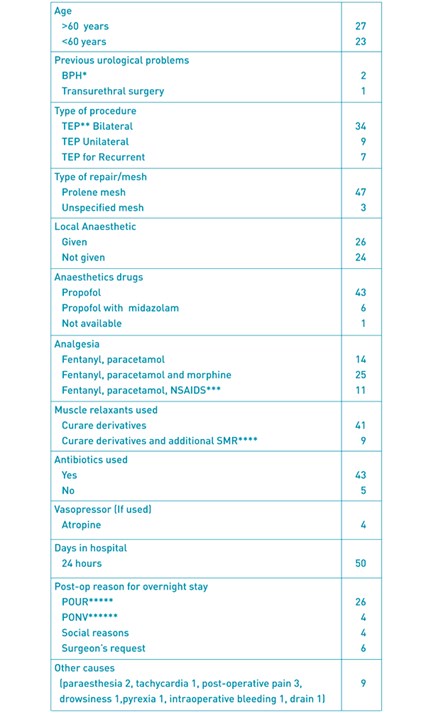

Methods: This is an analysis of case records for 50 individuals booked for day case surgery that had to be admitted overnight after laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery. A total of 287 procedures were done. Data for the individual, the type of surgery, anaesthesia and analgesia, post-operative management and causes of overnight stay were assessed.

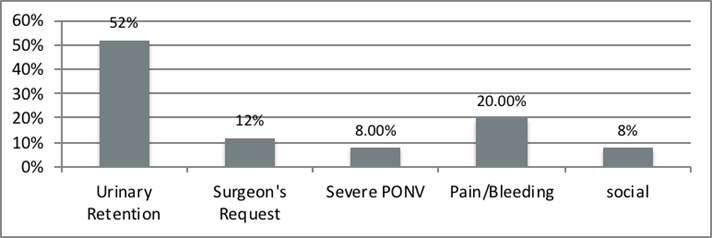

Results: The most common cause of overnight stay was found to be post-operative urinary retention. Not surprisingly, most were above the age of 60 but only three were known to have documented urinary problems in the past. Another factor was bilateral hernia surgery. Some patients were admitted for social reasons, post-operative nausea and vomiting, at the request of the surgeon and other uncommon causes. Nearly half of individuals were not administered local anaesthesia. 34 Individuals with bilateral hernia surgery stayed overnight on the ward.

Conclusion: The causes of failed discharges are multifactorial. Predictable delays in discharge for individuals above 60 years of age and those having bilateral surgery should probably have surgery early on the operating list. A protocol driven anaesthesia and pain control pathway should be followed. Social factors and fitness for laparoscopic surgery should be thoroughly assessed in the clinic to avoid unexpected admission.

Introduction

Inguinal hernia surgery is one of the most commonly performed procedures in the United Kingdom. Surgery is generally indicated in painful symptomatic hernias and to reduce the risk of future bowel obstruction or strangulation. It is perfectly reasonable to employ a ‘watchful wait’ policy in individuals that are asymptomatic though younger individuals are more frequently offered surgery than elderly asymptomatic ones. In a recent study it was suggested that 50% of watchful wait individuals crossed over to have surgery in a mean of 7 years. (1,2,3)

Open inguinal hernia repair with mesh, laparoscopic totally extra-peritoneal repair (TEP) or Trans-abdominal pre-peritoneal repair (TAPP) are the options of treatment. The type of approach depends on surgeons’ experience, patient choice, service provisions in the local hospital, technical and anaesthetic considerations. Laparoscopic surgery has become a standard of treatment for inguinal hernias. From the chronic pain perspective, earlier review of literature that compared laparoscopic with open surgery showed that laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery (LIHR) is more advantageous. Advantages are generally lesser pain, quicker recovery, earlier return to work and patient satisfaction compared to open surgery. (4)

Due to pressure on elective surgery and the need to ring fence beds in acute wards, there is a growing need to perform more operations as day case procedures. Day case units need to be fully functional independent units with dedicated day care ward staff, doctors, surgeons and anaesthetists. The Royal College of Surgeons and British Association of Day Surgery (BADS) have provided guidelines on managing patients having day case surgery. (5)

Most commonly referrals are received from the local general practitioner. A thorough assessment of the history and fitness for surgery is carried out in the clinic. As our general population is more obese and many are above the age of 60, it is important to be aware of their social history. Appropriate provisions must be made for them at home or be admitted overnight if they live alone or have special needs. In our practice, a referral to the pre-assessment clinic is made on the day of the surgical review. Our anaesthetists review the medical records for all individuals that are referred by the pre-assessment nurse. Individuals with ASA III (American Society of Anaesthesiologists) or ASA IV and high BMI (body mass index) of above 42 are not fit for day case surgery. They are booked on our main theatre lists in Maidstone Hospital.

Methods

We perform most of our elective inguinal hernias as day case procedures. The aim of the audit was to ascertain how many patients stayed overnight despite being deemed fit for a day case procedure.

This is a retrospective audit of all patients from Jan 2014 to August 2015 receiving elective laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair that stayed past midnight on the day of surgery. 287 laparoscopic inguinal hernias were performed. 50 patients stayed overnight post operatively. This was due to numerous factors. The most common cause being post-operative urinary retention (POUR). Normally the urinary bladder has a capacity of a volume of 400-600ml but POUR can occur with even a residual post voiding volume of 150ml in the bladder 6. POUR is defined as the inability to spontaneously pass urine requiring urethral catheterisation. The decision to catheterise is nurse led on the day case ward. This is based on the inability to pass urine for more than 6 - 8 hours postoperatively and the use of a portable bladder scanner to check the pre and post micturition bladder volume.

We have a dedicated day surgical unit in Tunbridge Wells Hospital. We have our planned elective lists in Maidstone Hospital. The day case unit has its own dedicated ward called Short Stay Unit with its own nursing, anaesthetic, and surgical staff. They also have an adjacent theatre recovery area. The patients have a nurse led discharge and are assessed for pain, ability to mobilise, oral intake, ability to pass urine and if required, have their venous thromboprophylaxis injection. The discharge letter is done by the operating surgeon or a junior doctor with the necessary postoperative advice and medications. Patients are provided with literature with a direct access phone number for the ward during opening hours and are asked to attend the Accident and Emergency Unit after the day unit is closed.

Coding of patient procedure (T20 and Y75.2) was used to identify all the cases that had laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery. The services of our medical records clerk helped us collect all the patients’ notes. Out of 287 individuals having laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery, 50 patients met the inclusion criteria with an age range between 25 - 85. All the data was compiled into an excel sheet.

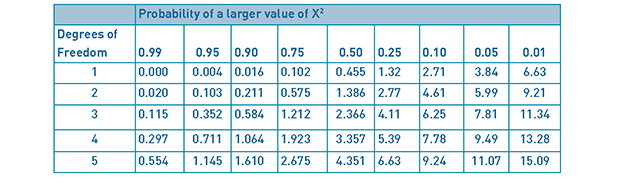

The patient data collected included age, previous medical history, type of surgical procedure, type of repair/mesh, local anaesthetic given, anaesthesia used, analgesics, antibiotics, days stayed in hospital and reason for overnight stay.

The Royal College of Surgeons guidelines were used to compare with our results. (5)

Results

There have been numerous papers that have evaluated POUR after inguinal hernia repair. (7,8,9,10) In this retrospective observational study we have looked into a wide range of causes of failed same day discharge.

We are seeing more patients above the age of 60 having day case surgery procedures. As far as age of our cohort of patients is concerned, 27 individuals out of the 50 overnight ward admissions were above 60 years of age. Despite not anticipating any risk factors of failed discharge when they were booked in for day care surgery, 15 of above 60 year old individuals had stayed overnight with POUR. Interestingly, only 3 were known to have benign prostatic hypertrophy or urethral surgical intervention in the past.

19 out of 50 patients having bilateral LIHR were above 60 years age. There were various reasons for failed discharge. The most common reason after POUR was social reasons, postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) and surgeon’s request. We were not able to look into the exact social causes that were specific to the individuals.

We performed bilateral LIHR on 34 individuals that failed to be treated as day case patients. It was observed that all patients had a combination of fentanyl, paracetamol, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents (NSAIDS) intraoperatively by the anaesthetists. 19 of the bilateral LIHR were, in addition to these painkillers, administered morphine intraoperatively or in the anaesthetic recovery area. A prolonged procedure in bilateral cases and difficulty in controlling pain might have resulted in an overnight stay. Unfortunately, we did not assess operating times for every procedure.

Muscle relaxation was either rocuronium or atracurium in these patients.

All of our patients had a standard LIHR with a Prolene mesh repair that was secured in the midline with tacks. These were absorbable and non-absorbable according to individual choice of the surgeon.

There was documentary evidence of local anaesthesia infiltration in 26 patients. The remaining 24 did not receive any local anaesthesia.

The Royal College of Surgeons guidelines for inguinal hernia surgery suggest avoiding the use of antibiotics as prophylaxis against mesh infection due to the lack of evidence to support it. Our study showed that most of our patients (45) out of 50 were prescribed antibiotics.5

Patient and surgery data

PH benign prostatic hypertrophy, **Totally extraperitoneal, ***Nonsteroidal anti-inflammtory drugs, ****skeletal muscle relaxation, *****post-operative urinary retention,******Post-operative nausea and vomiting

Figure 1: Bar chart for causes of overnight stay with relative frequencies

The audit was presented in our clinical governance meeting on the 14 January 2016.

The results were presented in the Association of Surgeons in Training meeting as a poster in 2016.

Discussion

Laparoscopic inguinal hernia surgery is being carried out as a day case procedure in the majority of regions in the United Kingdom and around the world. Assessment of fitness for day case surgery depends on numerous factors including surgical, medical, anaesthetic and social factors.

The British Association of Day Surgery recommends that 80% of inguinal hernia surgery is carried out as a day case operation11. Although all of our 287 patients were booked for a day case procedure, more than 80% were successfully treated and discharged the same day. There is a requirement for our day surgery unit to work closely with the primary care teams to avoid difficulty in postoperative rehabilitation. The individual is provided with a helpline number with 24 hours access after discharge.11 Our data does not take into account the failed discharges that were either admitted to accident and emergency or the acute ward after leaving the day unit. Many units that provide 24 hour access helplines advise callers to attend the accident and emergency department if the day case ward has closed for the day.

The POUR failed discharges of 9% are within the accepted figures of 1 to 22%81213. Many studies looked into the cause of acute urinary retention in laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. It has been proposed that excessive narcotic use over 6.8 mg of morphine or over could predispose to POUR. This was in a study of 28 individuals with POUR from a total of 346 having the surgery9. The study size we believe was not significant enough to provide conclusive evidence against the optimal dose of morphine.

Another study reviewed many variables to help predict the individuals with POUR. This was a retrospective review of cases that identified age above 60 years, history of previous BPH and total anaesthetic time to be risk factors for POUR on univariate and multivariate analyses. 12 individuals had benign prostatic hypertrophy, 6 with urine voiding problems in the past and 4 with prostatic cancer. Interestingly, 5 patients were discharged home without having passed urine and were admitted the next day for urinary catheterisation in this review of data.13

The use of intravenous fluid therapy intraoperatively and post operatively of one litre or above has shown an increase in risk of POUR. The confounding factor with intravenous fluid therapy was administration of opioid analgesia postoperatively.14 The bladder stretch from intravenous therapy was thought to reduce detrusor contraction. It is also hypothesized that surgery in close proximity to the bladder in laparoscopic surgery affects bladder activity. Koch et al mentioned in his study that the use of mesh fixation devices whether absorbable or non-absorbable increase the need of intraoperative narcotic analgesia and POUR. Eliminating the use of fixation devices were shown to reduce pain killer requirements and risk of POUR. Mesh fixation devices were used in all of our patients.15

A centre approached the issue of POUR with various interventions like prescribing an alpha 1 blocker preoperatively and post operatively. This has shown a reduction of POUR in high risk patients with lower urinary tract symptoms. The criticism is that this intervention was on open surgical procedures without a mesh (Bassini and Darn repair). We know laparoscopic surgery carries a higher risk of POUR compared to open surgery.16 In another centre it was shown that prevalence of lower urinary tract symptoms increases per decade increase in age and an alpha blocker can prevent POUR.17

Recently, a review of the pathophysiology, risks, complications and treatment of POUR were discussed with a thorough assessment of treatment options from urethral bladder catheterisation to prostatic surgery. It was stressed that POUR is a surgical emergency that can cause acute renal failure and postoperative diuresis.6

Optimisation of pain relief intraoperatively and post operatively can improve outcomes and early discharge. As day case surgery is evolving, medications are being used that have lesser adverse outcomes. As an example, it has been shown that remifentanil seems to have shown lesser adverse events for the day case patients than fentanil.18 Similarly Infiltration of local anaesthetic prior to starting the procedure has been shown to reduce the requirements of prolonged anaesthesia, intravenous analgesia, post-operative opioid use and hence early mobilisation.19

One interesting aspect that could improve day case experience is the continuity of care in healthcare. This is a concept of seeing the same named staff nurse and surgeon peri-operatively. This enhances the patient experience, confidence and understanding of the pathway by the patient and the healthcare staff. High patient turnover and staff shortages can hinder this but could be gradually implemented at certain designated levels like nursing and doctors.20

Better continuity of care and understanding of the postoperative pathway could lead to lesser overnight stay. This can better help avoid the unexpected admissions overnight for social reasons and a better understanding of the personal circumstances of the individual.

Unfortunately there are always going to be post-operative factors that will prevent early discharge. We admitted 9 individuals with various minor nonspecific postoperative complications like transient paraesthesia, presence of a drain, drowsiness, intra-operative bleeding, nonspecific tachycardia, post-operative pain and post-operative pyrexia.

We also had 6 unavoidable admissions on the operating surgeon’s request. These were due to technical difficulties in surgery and due to overrunning operating lists.

Numerous centres have gone one step forward and performed ‘one stop shop’ LIHR. The individual is seen, assessed anaesthetically, operated upon and discharged the same day. Although this would have huge implications on the organisation of the patient journey in a busy and high volume unit in the National Health Service, this could be a useful option to reduce waiting lists by choosing the more suitable patients for LIHR.21,22

Although many studies have looked at reasons for POUR but there is a lack of evidence looking into all general causes of failed discharge. This audit has its limitations as it was a retrospective review of our quality outcomes however, we have looked into all causes of failed discharge. It is the author’s experience that many individuals are booked as day case LIHR by doctors not experienced in LIHR. Additionally, some technical factors like previous surgery are not absolute contraindications but affect operating time and rarely may warrant overnight observation.

Slight variation in clinical practice exists amongst surgeons. On the day of the surgery an open repair might be converted to LIHR because of patient choice or incidental finding of bilateral hernias. Unfortunately, despite evolving practice, some individuals are still not given the options and are only booked for open surgery.

Article continues after ad.

Conclusions

This audit highlights the complexities of day care surgery and multifactorial issues surrounding optimising post-operative care. Factors like age above 60 years, bilateral LIHR and pain management need to be kept in mind in booking the surgery. Better awareness of the social circumstances and close work up with pre-assessment and clinical staff is required to avoid unnecessary post-operative failed discharges. A simple checklist for assessing the suitability for LIHR could guide junior doctors in booking cases appropriately in clinic.

References

- The Herniasurge Group, Simons MP, Smietanski M, et al. International guidelines for groin hernia management. Hernia. 2018.

- Gong W, Li J. Operation versus watchful waiting in asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic inguinal hernias: The meta-analysis results of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2018. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2018.02.030

- O’Dwyer PJ, Norrie J, Alani A, Walker A, Duffy F, Horgan P. Observation or operation for patients with an asymptomatic inguinal hernia: A randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg. 2006. doi:10.1097/01.sla.0000217637.69699.ef

- Kuhry E, Van Veen RN, Langeveld HR, Steyerberg EW, Jeekel J, Bonjer HJ. Open or endoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair? A systematic review. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2007. doi:10.1007/s00464-006-0167-4

- Sanders, David L KM. Commissioning guide: Groin hernia Commissioning guide 2013. Br Hernia Soc Groin Hernia Guidel. 2019;(October 2013):58.

- Kowalik U, Plante MK. Urinary Retention in Surgical Patients. Surg Clin North Am. 2016. doi:10.1016/j.suc.2016.02.004

- Sivasankaran M V, Pham T, Divino CM. Incidence and risk factors for urinary retention following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.06.005 [doi]

- Sivasankaran M V., Pham T, Divino CM, et al. Incidence and risk factors for urinary retention after endoscopic hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2013. doi:10.1007/s00464-013-3119-9

- Patel JA, Kaufman AS, Howard RS, Rodriguez CJ, Jessie EM. Risk factors for urinary retention after laparoscopic inguinal hernia repairs. Surg Endosc. 2015. doi:10.1007/s00464-014-4039-z

- Hudak KE, Frelich MJ, Rettenmaier CR, et al. Surgery duration predicts urinary retention after inguinal herniorrhaphy: a single institution review. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2015. doi:10.1007/s00464-015-4068-2

- Verma R, Alladi R, Jackson L, Al E. Day case and short stay surgery: 2. Anaesthesia. 2011. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2011.06651.x

- Lau H, Patil NG, Yuen WK, Lee F. Urinary retention following endoscopic totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernioplasty. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2002. doi:10.1007/s00464-001-8292-6

- Sivasankaran M V., Pham T, Divino CM. Incidence and risk factors for urinary retention following laparoscopic inguinal hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2014. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2013.06.005

- Koch CA, Grinberg GG, Farley DR. Incidence and risk factors for urinary retention after endoscopic hernia repair. Am J Surg. 2006. doi:S0002-9610(05)00921-9 [pii]

- Koch C a, Greenlee SM, Larson DR, Harrington JR, Farley DR. Randomized prospective study of totally extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair: fixation versus no fixation of mesh. JSLS. 2006.

- Mohammadi-Fallah M, Hamedanchi S, Tayyebi-Azar A. Preventive effect of tamsulosin on postoperative urinary retention. Korean J Urol. 2012. doi:10.4111/kju.2012.53.6.419

- Shaw MK, Pahari H. The role of peri-operative use of alpha-blocker in preventing lower urinary tract symptoms in high risk patients of urinary retention undergoing inguinal hernia repair in males above 50 years. J Indian Med Assoc. 2014.

- Palumbo P, Usai S, Amatucci C, et al. Inguinal hernia repair in day surgery: The role of MAC (Monitored Anesthesia Care) with remifentanil. G di Chir. 2017. doi:10.11138/gchir/2017.38.6.273

- Radwan RW, Gardner A, Jayamanne H, Stephenson BM. Benefits of pre-emptive analgesia by local infiltration at day-case general anaesthetic open inguinal hernioplasty. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2018. doi:https://dx.doi.org/10.1308/rcsann.2018.0059

- Suominen T, Turtiainen AM, Puukka P, Leino-Kilpi H. Continuity of care in day surgical care - perspective of patients. Scand J Caring Sci. 2014. doi:10.1111/scs.12099

- Jutte EH, Cense HA, Dur AHM, Hunfeld MAJM, Cramer B, Breederveld RS. A pilot study for one-stop endoscopic total extraperitoneal inguinal hernia repair. Surg Endosc Other Interv Tech. 2010. doi:10.1007/s00464-010-1035-9

- Voorbrood CEH, Burgmans JPJ, Clevers GJ, et al. One-stop endoscopic hernia surgery: efficient and satisfactory. Hernia. 2015. doi:10.1007/s10029-013-1151-2

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6048/284-raza.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse5

Author

Fiona Belfield Uwch Brif Nyrs DSU/Senior Sister DSU

Ysbyty Llwynhelyg/Withybush General Hospital, Wales

The Council members started to arrive on Wednesday to prepare for the Conference; first impressions of the venue were impressive with plenty of space. Once we familiarised ourselves with the venue we were all set for the next two days, which promised to be informative, educational and inspirational.

Thursday

Given the increased numbers from last year, registration was brisk and Council members were on hand to direct delegates who were presenting and displaying posters to the relevant areas. The Conference was opened by President Mary Stocker welcoming everybody to Sheffield once the housekeeping notes were given by Paul Rawling (Honorary Secretary) it was straight into the first plenary of the conference. Miss Elizabeth Moulder Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon and her team from Hull gave us a detailed inspirational presentation on their experiences in developing a Day Case Hip replacement pathway. This was well attended and provided food for thought to encourage others. It was great to hear firsthand the patient experience as the first patient who was suitable for this pathway was invited to speak about his experiences. The main message from the session was that it is the hard work and determination of the entire multidisciplinary team which is making this a successful pathway and hopefully the delegates who attended the session left empowered and encouraged to share Hull’s experience within their own teams.

The second plenary was related to workforce in Day Surgery. The session started with Mona Guckian Fisher who was speaking on behalf of the Association For Perioperative Practice(AFPP), who gave us an overview of some of the projects that the AFPP had been working on with regards to the surgical first assistant role and how they can fit into a Day Surgery environment, the second speaker of the session was Anitha Rego, who is a Practice Development Practitioner from Torbay Hospital and she gave the delegates her experiences on how the role of the Assistant Practitioner role could be adapted into the day surgery environment.

The third plenary was entitled ‘What has changed for children in Day Surgery’ this session was delivered by Dr Judith Short who is a Consultant Anaesthetist working in Sheffield Children’s hospital. Judith gave an engaging presentation in the changes over the last 10 years with regards to the developments in the patient and family journey, with practical ideas in helping improve the patient and family experience, from Preassessment to discharge.

After lunch it was the 1st of 2 parallel session of free papers, this year saw an increase in submissions for papers and posters which is always encouraging. The standard was high and it is always interesting to see the varieties of topics being presented; on a wide range of subjects. This year was no exception and some of the subjects discussed were ‘Current practice in Day Case plastic surgery’; ‘Antibiotic cover for TRUS biopsy’; ‘Introduction of Uni-compartment knees replacement as a day case’; ‘Day Case emergency surgery’; ‘Patients with Obstructive sleep Apnoea’ and ‘Day Case breast Surgery.’

This year there were 3 parallel sessions which were entitled ‘Training’ chaired by Mr. Dave Bunting, Dr Theresa Hinde plus our BADS Council trainee members, ‘Sustaining performance using mindfulness’, with Mari Lewis and ‘Nursing’ chaired by Mrs. Fiona Belfield and Mrs. Alex Alen. These sessions have proved very successful in past conferences and this year didn’t disappoint. The mindfulness session was the first time that BADS had run this and having spoken to delegates that attended the session they felt very calm and relaxed after, and gained tips on how to control their stress within the work environment. The other sessions were well attended and hopefully the delegates gained/shared knowledge amongst each other that they will take back to improve their own practice and share with colleagues.

Following on from this was the 2nd parallel free paper sessions, again these were well presented and a wide variety of topics were discussed including ‘Day Case Shoulder replacement’; ‘Day case surgery and surgical training’; ‘Body mass index impact on surgical outcomes and cost for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy’; ‘Formulation of an anesthetic Day Surgery reference guide’; ‘Same day discharge following knee Arthroplasty’ and ‘Local anaesthetic patients getting the service they deserve’.

The Annual General Meeting closed the end of the first day, with the President detailing what BADS Council had been working on throughout the year, which includes development of the electronic journal and journal app, on-line conference programme, updated website and Model Hospital, all of which are exciting advancements for BADS. The President informed delegates that BADS are now fully compliant with the new data protection law (GDPR) that came into operation in May this year. The President welcomed 4 new members onto council, namely David Bunting, Jan Howells Johnson, Alex Alen and Sandra Briggs and updated the members on who were going to be taking up new roles within council. The AGM also included reports from the Treasurer, Honorary Secretary and the Publications officer. Once the AGM drew to a close it was time for all to prepare for the networking dinner, which this year was held in Cutler’s Hall. The venue was suburb and the food was excellent and all who attended enjoyed the evening and felt it was an opportunity to network in a relaxing environment.

Friday

The 1st session of the day (Plenary 4) saw Mr Dave Bunting Consultant Upper GI Surgeon from North Devon District Hospital, Barnstable talk about Day case laparoscopic cholecystectomy 10 years on and Devon’s experience in the Chole-QuIC which is a project introduced by the Royal College of Surgeons to aim to reduce waiting times for cholecystectomy for eligible patients with acute biliary pain or cholecystitis or gallstone pancreatitis, by using quality improvement techniques to empower teams within Hospital trusts. Mr. Paul Super Consultant Upper GI Surgeon from Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham talked about Day case reflux surgery, and how this has evolved over the last 15 years. Both presentations were informative and educational, even though laparoscopic cholecystectomies have been included in BADS Directory of procedures for many years; it is still in the forefront of day surgery and continues to provoke topical debate.

The next session was the prize paper session, which saw five delegates present their papers, this year was a very high standard and the topics were ‘Patient Experience and Outcomes after Prilocaine spinal for Anorectal Surgery’; ‘Developing a day case pathway for laparoscopic pyeloplasty’; ‘Water Intoxication after a Day Case Surgery’; ‘The Redundant Role of Preoperative Group and Safe for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy’ and ‘Analysis of Care Efficiency for patients with Acute Appendicitis suggests Ambulatory Management’. The vote for the best presentation went to Nick Li, presenting on the ‘Redundant role of the Group and save preoperatively.

Well done to all those who presented papers or posters in this year’s conference, again the standard of the posters displayed in the exhibition area was exceptional and BADS encourages any presenters (oral or poster) in this year’s conference to submit their work for publication in the Journal of One Day Surgery (JODS).

Plenary 6 was presented by Dr Rhona Siegmeth, Consultant Anaesthetist from Golden Jubilee Hospital, Glasgow. She gave a very thought provoking presentation on ‘When things go wrong in day surgery’. Rhona went into detail the process to go through and gave examples of real situations that she has dealt with and the outcomes. If there was one lesson to be learnt from the session and that was to always be open, honest, and say ‘sorry’ if you are unfortunate to be in a situation requiring this advice, also clear concise documentation is the key to help with any investigation. This of course applies to all medical and nursing staff alike, which is why this session was well received by all as it was relevant to all disciplines.

The penultimate session of the conference was Sister Ruth Roddison who is a Lead Specialist Nurse; Inpatient pain team at Rotherham Foundation Trust Hospital, her presentation was titled ‘Pins and Needles using acupuncture (Acupin) to prevent Post-Operative Nausea and Vomiting (PONV)’. Again, this was an interesting session informing the delegates on how they have introduced the process of using Acupins as a method of reducing PONV. It was initially a trial starting with Gynecological patients but has now been introduced to Orthopaedic patients and also ladies suffering from hyperemesis gravidarum. This is due to the success of the trial and the cost effectiveness of the process but most importantly the success rate for the patient, as PONV can be debilitating for any patient.

Our final plenary of the conference was how we started the conference with an orthopaedic session, this time detailing the experiences of Mr Ben Gooding, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon from Nottingham and Dr Nigel Bedforth, Consultant Anaesthetist also working in Nottingham, who talked about their experiences in setting up ‘Awake Shoulder Pathway’. This was a very informative session which gave the delegates a detailed description on how in Nottingham they have set up a very successful service with high patient satisfaction. Both presenters spoke on their techniques in achieving a high success rate for this surgery. The key to the success of this pathway was the introduction of ultrasound guidance for regional anaesthesia, which enables accurate administration of local anaesthesia and ensures safer techniques for the patient. Coupled with the advancements in Shoulder Surgery over the last 20 years with the development of arthroscopic techniques, it has enabled sub-acromial decompressions, rotator cuff repair and shoulder replacement among other procedures to be carried out in a day surgery setting.

And so that session closed another successful conference and certainly some food for thought for all who attended the conference. Hopefully, when all the presentations of all the inspirational work which is being carried out throughout the country is taken back to the delegates work base, they will be motivated and enthusiastic to act upon what they have learnt to develop/ improve their practices to ensure patients benefit.

A big thank you to all the speakers who contributed to this year’s conference and in giving up their time to help make this such a successful ASM and of course for the delegates who attended and also contributed to the discussions, as without the delegates there would be no ASM!!!

We look forward to seeing you in London 2019.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/6049/284-asm-2018.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1337#collapse6

Authors

Varnavas Michalis, Manash Debbarma, Ram Beekharry & Nirgan Gogoi

Department of Urology, Mid Yorkshire NHS Trust, Pinderfields General Hospital, Aberford Rd, Wakefield WF1 4DG.

Corresponding author

Michalis Varnavas

St James University hospital, Urology Department, Beckett St, Leeds LS9 7TF.

Email: michail11@hotmail.co.uk

Keywords: Greenlight XPS, prostatectomy, Day Case Surgery

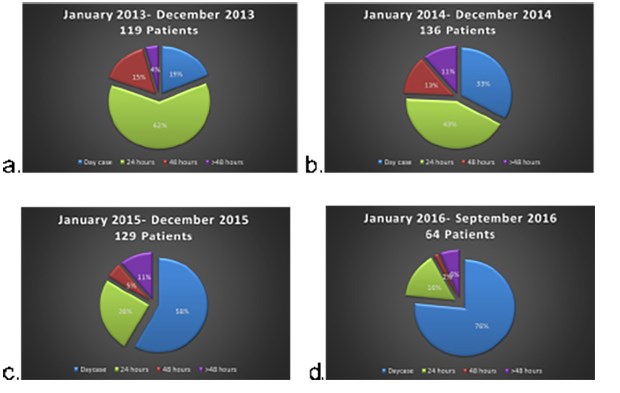

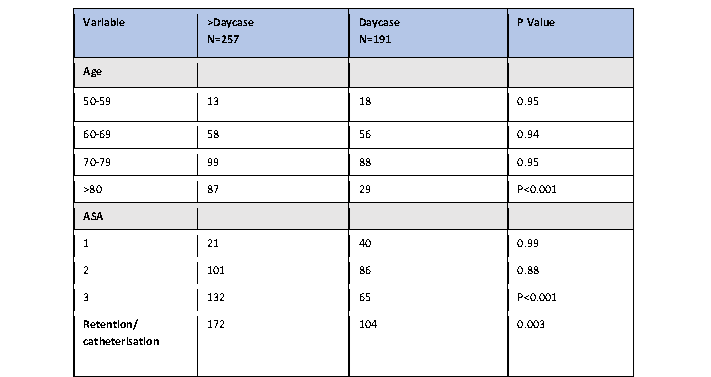

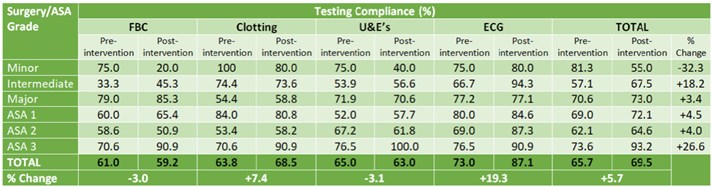

Abstract