Dave Bunting

This edition of JODS is published at an exciting time of year in the BADS calendar when we are preparing for the 30th BADS Annual Scientific Meeting, this year to be held at the Royal Society of Medicine in London on 27th and 28th June. We have received a large number of high-quality abstracts, of which 30 will be presented orally and many more in poster form. The programme for the meeting includes talks from speakers on a variety of topics covering general surgery, urology and gynaecology themes as well as talks on new technology, benchmarking and going green in ambulatory surgery! There will also be workshops on spinal anaesthesia, discussing the need for post-operative carers and optimising your day case pathway as well as a debate on whether slow surgeons/anaesthetists should be banned from the day surgery unit, which promises to generate an interesting discussion. A link to the full programme can be found in this edition of JODS via the contents page. Please also consider downloading the new Conference App, launched for this year’s meeting via the links below, especially if you are planning to join us at the conference next month:

BADS 2019 Conference Apps

Android App:

https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=badsconference.droid&hl=en_GB

Apple App:

https://itunes.apple.com/gb/app/bads-conference/id1446266263?mt=8

This edition of JODS contains an original article on paediatric opiate use after hernia repair, an audit of the recording of Hba1c and blood pressure in elective surgical referrals from primary care, a report of a new, simple technique for managing the difficult to deal with problem of a buried PEG tube bumper and a report of a closed audit loop on training opportunities in day surgery.

Immediately following this editorial, you will see the President’s letter from Mary Stocker. This is in fact Mary’s last letter as President before she hands over to our President Elect Kim Russon. I would like to take this opportunity to thank Mary for her excellent stewardship over the past 3 years. Under her leadership, BADS membership has grown and the organisation has undergone a number of important developments. JODS underwent transition to the popular app and web-based electronic formats; the BADS website has undergone redevelopment and Mary has worked together with a number or organisations to provide benchmarking, to deliver guidance on developing day surgery pathways and to host a wide range of educational events and meetings across the UK. In a financially-challenged, resource-limited NHS, never before has the day surgery agenda been more important and Mary has worked relentlessly to promote and enhance the benefits day case and short stay surgery have to offer.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26183/291-editorial.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse0

As I write my final letter to you as President, I am really pleased to be able to share a number of initiatives with which BADS have been recently collaborating. The last few months have been extraordinarily busy for a number of council and I am very grateful to them for all their hard work. The long awaited joint publication between BADS and the Association of Anaesthetists has now been finalised and is available via the AAGBI website: https://anaesthetists.org/Home/Resources-publications/Guidelines/Day-case-and-short-stay-surgery. This, along with the GPAS guidelines produced jointly with the Royal College of Anaesthetists, is an extremely useful resource which I would recommend to anyone involved in aspects of management of a day surgery service. Members of Council are also currently contributing to the Royal College of Anaesthetist Curriculum and also redesigning the day surgery section of their Compendium of Audit Recipes. We hope both of these will be released in the autumn.

The 6th edition of our Directory of Procedures is now in print and will be launched at our Conference in June. It will also be available for purchase via the website so time to “throw out the orange and bring in the blue”! We are currently working with the team from the model hospital who are updating their day surgery compartment to reflect the new benchmarking figures and procedures within the 6th edition. This too should be available for release to coincide with our conference. One of the major revolutions in day surgery in the past 2 years which is reflected within the Directory is the advent of total hip and knee replacements as day surgery. We have run a number of events over the past year supporting and educating teams who wish to launch a day surgery arthroplasty service. We are currently collaborating with the team from Northumberland to run a series of events and have places available on courses in Manchester in June and Newcastle in October. Details are on the website. A joint publication by BADS and the Northumberland team about setting up a day surgery arthroplasty service is also available via our website.

Over the past few months council members have run and lectured at a large number of meetings:

- in Edinburgh in collaboration with the Scottish government where it was great to see such enthusiasm for day surgery development from our colleagues north of the border

- with Healthcare Conferences we have run or contributed meetings on hip surgery, theatre efficiency and day case general surgery

- next week a number of us will be heading over to beautiful Porto to represent BADS at the International Association of Ambulatory Surgery. It’s not too late to book your tickets and join us!

Recent collaboration with the teams from Getting it Right First Time (GIRFT) is proving productive to both us and GIRFT and we are delighted to be forging strong links with their national clinical advisors to ensure that day surgery is well represented within the GIRFT surgical programmes.

As I sign off on my last President’s letter I would like to express my huge thanks to all members of council who have supported me through the 3 years I have been in post. However particular recognition should go to Anna Lipp my predecessor who stands down from Council next month after more than 13 years of service not only as president but previously as publications committee lead. Anna has always been a voice of reason and common sense, she has worked tirelessly for the Association for many years, her contributions have been invaluable and we are extremely grateful for all her hard work. I would also like to publicly express my gratitude to Nicola Adams, our administrator ,for her hard work and constantly keeping the show on the road for us all. Finally, Paul Rawlings stands down from Council this year and we are very grateful to Paul for stepping into the role of Honorary Secretary at very short notice and doing such a good job during his 4 years in post. As I hand over as president I know I am leaving the Association in excellent hands with Kim Russon taking over as President and an excellent team on Council to support her. Thank you to you all for your support, encouragement, contributions and enthusiasm and if you have not booked your place for our conference in June please do, we would love to see you all there.

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse1

Click to open the pdf of this year's programme.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/25667/asm-2019.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse2

Hope Wilkinson MD1, Kimberly Somers PA-C1,2, Melissa Lingongo1,2, and Casey Calkins MD1,2

1 Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, Department of Surgery, 8900 W. Doyne Avenue, Milwaukee, WI 53226.

2 Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, WI, 999 92nd Street, Suite CCC320, Milwaukee, WI 53226.

Corresponding author: Hope Wilkinson MD, 999 92nd Street, Suite CCC320, Milwaukee, WI 53226.

Tel: (414) 266-6550 E-mail: khopewilkins@mcw.edu

Author Disclosure Statement

None of the four authors have any financial or personal relationships with organizations or people which could bias this work and conclusions.

Key Words: day surgery, pediatrics, narcotics, opioids, hernia repair

Abstract

Background: The ideal postoperative pain management regimen after outpatient pediatric surgical procedures is not known. We hypothesized that the use of non-opioid medications alone would provide adequate postoperative analgesia compared to those patients receiving opioids after pediatric herniorrhaphy.

Methods: A retrospective chart review of patients undergoing umbilical, inguinal and epigastric hernia repair at a US children’s hospital during 2017 was conducted. Individual physician practice dictated whether opioids were prescribed. Data extracted included age, sex, procedure, pain medications prescribed and follow-up visits within 30 days of surgery. The Wisconsin Electronic Prescription Drug Monitoring Program was queried to determine whether opioid prescriptions had been filled. Calls were conducted 24 to 72 hours after surgery to assess for pain control, nausea/emesis, and wound issues.

Results: Of the 564 children included, 383 (68%) of children received prescriptions for opioids, of which 233 (61%) were filled. The average opioid prescription was for 6.4[1-29] doses. Among the 59% of patients who answered follow up calls, 97% reported pain as controlled and 7% reported nausea/emesis. Patients who received an opioid prescription exhibited the same rate of pain control (97%) as those who did not receive or fill an opioid prescription.

Conclusion: Non-opioid medications are effective in controlling postoperative pain after pediatric herniorrhaphy. Routine opioid administration does not change parent reported uncontrolled pain following ambulatory inguinal, umbilical or epigastric hernia repair compared to non-opioid pain management. A guideline promoting the use of non-opioid analgesia following pediatric herniorrhaphy is likely to decrease opioid use while offering adequate post-operative analgesia.

Introduction

Introduction

Pain is an expected consequence of surgery, but the ideal postoperative pain management regimen after uncomplicated outpatient pediatric surgical procedures has not been well established in the literature. Additionally, the rise in outpatient day surgery procedures means that parents are now responsible for management of post-operative pain control. Two recently published studies which involved surveying parents and guardians regarding post-operative outpatient pain management found that analgesics were dosed correctly only 44 – 55% of the time.1,2 Additionally, Rony et al. reported that 73% of parents and guardians use of medications was influenced by worries about adverse effects from post-operative pain medications. This is consistent with findings that parents and guardians have a low rate of delivery of post-operative analgesia (opioid and non-opioid) to children following day surgery, with between 24 – 32% of children receiving 1 dose or fewer.1-3 A retrospective cohort study of healthy pediatric patients in Tennessee enrolled in Medicaid without major chronic disease or prolonged hospitalization found an opioid prescription prevalence of 15% for all children, most commonly after outpatient procedures (56%).4 They also found a cumulative incidence of opioid-related ED visits, hospitalizations or death of 38 per 100,000 prescriptions.4 In randomized control trials comparing post-operative opioid analgesia to ibuprofen in pediatric patients, the use of opioids was associated with more nausea, vomiting, drowsiness and dizziness5; and more night time oxygen desaturations.6 Given the perilous nature of opioid over-dose, as well as the continued opioid epidemic, it is imperative to thoughtfully examine whether post-operative opioid analgesia is necessary and beneficial in children undergoing outpatient surgery.

The aim of this study was to examine the effects of postoperative oral opioids on short term outcomes of pediatric patients undergoing outpatient hernia repair. A retrospective review of all outpatient hernia repairs performed at a large free-standing academic children’s hospital in 2017. We hypothesized that the use of non-opioid medications alone would provide adequate postoperative analgesia compared to opioid administration after uncomplicated pediatric herniorrhaphy.

Methods

A retrospective chart review was conducted of all patients less than 19 years of age undergoing umbilical, inguinal and epigastric hernia repair at the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, a single US free-standing children’s hospital, during one calendar year (2017). Patients were excluded if discharge did not occur within 24 hours of surgery or if patients had undergone other procedures, including tympanostomy tubes, tonsillectomy, pyloromyotomy, and laparoscopic appendectomy concurrently. The study was approved by the Children’s Hospital of Wisconsin IRB (1216340-1, May 31, 2018).

Individual physician practice dictated whether opioids were prescribed. Data extracted included age, sex, procedure, pain medications prescribed and prescriber and follow-up visits within 30 days of surgery. At our institution, standardized follow-up calls are conducted between 24 and 72 hours following surgery to assess for pain control, nausea/vomiting, constipation and wound issues. Parents serve as the primary source of information in children unable to answer the questions reliably in the post-operative follow up calls, and responses are recorded in the electronic medical record.

The Wisconsin Electronic Prescription Drug Monitoring Program (ePDMP), a Wisconsin state website, is a central resource to see if opioid prescriptions have been filled. The ePDMP was queried for those patients who received an opioid prescription to determine if the prescriptions had been filled.

The primary outcome was reported pain control on follow-up phone call. Secondary outcomes included reported nausea and vomiting on the follow-up phone call and ER visits related to uncontrolled pain, nausea, vomiting, constipation or other adverse effects of opioid medications. Number needed to harm was calculated based on secondary outcomes. When comparing cohorts of children exposed to outpatient opioids and those not exposed, children < 2 years of age were excluded from analysis given the low rates of prescribing in those age groups (25% of children < 2 years old received opioid prescriptions compared to 81% of >2-year-olds) and concern about skewing of the analysis. Descriptive statistics of categorical variables were calculated as totals and percentages and compared with a χ-squared test or Fischer’s exact when appropriate. Aggregate rates were compared using one-way ANOVA. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics version 24 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

Results

Overall, 564 primary hernia repairs were performed by ten pediatric general surgeons at CHW during the study period. Slightly more than half, 55.5%, of patients were male. Each surgeon preformed between 26 and 100 cases. A majority of children, 67.7%, were given a prescription for opioids and 55% of children were given a prescription for a non-opioid pain medication (i.e. acetaminophen or ibuprofen). Of the opioid prescriptions given to parents and guardians, 62% were filled. The average opioid prescription was for 6.4[1-29] doses.

Children undergoing umbilical or epigastric hernia repair were more likely to receive an opioid prescription than those undergoing inguinal hernia repairs (77.7% v. 54%, p < 0.0001). However, procedure type did not affect the likelihood children received a non-opioid prescription or filled their opioid prescriptions (53.8% v. 55.4%, p = 0.272; 45.4% v. 37.2%, p = 0.294), (Table 1).

Older children were more likely to receive opioid prescriptions, as 95% of children over the age of 12 received opioid prescriptions compared to 76% of 1 to 3-year-olds (p < 0.0001), (Figure 1). The mean number of doses prescribed to children ages 6 months – 12 years was between 5.14 and 5.67 doses. However, for children > 12 years, the average number of doses of opioid prescribed was 9.2 ± 5.95. Older children were also more likely to have their prescription filled. In our study, children ages 6 months – 12 years, filled between 54% - 69% of prescriptions and children > 12 years old filled 83% of prescriptions.

Attending physicians were most likely to prescribe opioids (92% of the time) compared to residents (55%), fellows (66%) and advanced practice providers (i.e. Nurse practitioners and physician assistants) (APPs) (27%). Attending surgeons prescribed the lowest mean doses 5.5[2 – 20] and fellows the highest 7.2[3 – 29]. APPs were most likely to write for non-opioid adjuncts and prescribed them 91% of the time. Receiving a non-opioid prescription was not associated with a decreased likelihood of filling any opioid prescriptions (50.8% v. 49.2%, p = 0.770).

More than half of patients, 334 (59%), had a parent or guardian who responded to a follow up call. For those who responded, 97% reported pain as controlled: there was no difference among patients receiving an opioid prescription compared to those who did not (98% v. 94%, p = 0.06). Overall, 7% of parents or guardians reported nausea/emesis after discharge in their child. In those children older than 2 years of age who filled an opioid prescription, 12% reported nausea/emesis versus 4.4% of patients who received but did not fill an opioid prescription (p = 0.04), (Table 2). Additionally, in those children older than 2 years of age who filled an opioid prescription 2.8% reported uncontrolled pain compared to 2.6% of patients who received but did not fill an opioid prescription (p = 0.92). Based on reported nausea and vomiting at the time of the follow-up phone calls, the number needed to harm in our study by an opioid prescription is 13.2 patients.

A significant number of children, (11%), had an unscheduled visit to the general surgery clinic, their pediatrician, urgent care or emergency department within the CHW electronic health record within 30 days of surgery; the majority of visits were not related to the procedure (viral infections, otitis media, etc.). Two children without an opioid prescription (1%) sought care for postoperative pain. Five children who filled an opioid prescription (1.3%) sought care in the emergency department or clinic for constipation, nausea or emesis compared to two children (1%) who did not receive an opioid prescription (p = 0.55). Additionally, there were eight phone calls within POD 0-7 regarding nausea, vomiting or constipation, from parents or guardians of children who had received and filled opioid prescriptions, compared to two phone calls from children who had either not received an opioid prescription or not filled their prescription (3.4% vs.0.6%. p = 0.01).

Article continues after ad.

Discussion

For pediatric patients undergoing outpatient hernia repair non-opioid analgesia appears to be equivalent to opioids, with overall 97% reporting pain as controlled on follow-up phone calls. In children who received opioid prescriptions 62% were filled. Similar to what is described in the adult literature, the pain medication received by patients varied by the procedure performed with umbilical hernia patients being more likely to receive opioid prescriptions than inguinal hernia patients.7-9 Both Overton et al. and the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborate recommend more opioid doses following umbilical hernia repair than inguinal hernia repair in adults.8-9 Clearly, adult guidelines cannot be uniformly applied to children. Review of national prescribing habits following pediatric umbilical hernia repair by Cartmill et al., found that 52% of children undergoing umbilical hernia repair filled an opioid prescription with half of children receiving a prescription for greater than 3 days, this compares similarly to our institution were 41% of opioid prescriptions were filled after outpatient pediatric hernia repair.10

Our review showed a mean number of prescribed doses of 6.4 doses with a range of 1 – 29. Only one patient, who had received 4 doses, called for a re-fill. At our institution, attending surgeons prescribed the lowest mean doses 5.5[2 – 20] and fellows the highest 7.2[3 – 29]. This is similar to what was seen in an adult retrospective review of general surgery discharges in which residents and APP prescribed higher doses than attending surgeons.11 APPs were more likely to write prescriptions for acetaminophen and ibuprofen; however, any change in patient compliance with these medications after receiving a prescription is not known.

In our study there was no significant difference in the percentage of surveyed parents and guardians reporting their child’s pain as well controlled at follow-up phone call between those that received and filled opioid prescriptions and those without opioids in the home (2.6% v. 2.8%, p = 0.92). This observation is supported by several double-blinded randomized controlled trials showing no significant difference in children’s pain when receiving either an opioid or ibuprofen following discharge after tonsillectomy, extremity fracture or outpatient orthopedic surgery.5-6,12 Furthermore, data from a randomized controlled trial in adults also supports the equivalence of ibuprofen and acetaminophen compared to acetaminophen and an opioid for acute pain control when presenting to the ED with moderate to severe acute extremity pain.13

A retrospective cohort study between 1999 – 2014 which reviewed all children in Tennessee on Medicaid between 2 and 17 years old who did not have a major chronic disease or prolonged hospitalization found a cumulative incidence of opioid ED visits, admissions and deaths of 38 per 100,000 prescriptions with a number needed to harm of one adverse event for every 2611 opioid prescriptions .4 Randomized control trial data comparing opioid analgesia to ibuprofen found more nausea, vomiting, drowsiness and dizziness and more night time oxygen desaturations.5-6 In our study, patients who filled opioid prescriptions were more likely to have nausea and vomiting on follow-up phone calls (12% v. 4.4%, p = 0.04) and made more calls to the general surgery clinic with complaints of constipation (3.4% v. 0.6%, p = 0.01).

Our study is limited in its nature as a retrospective review of a single institution. Our data reflects our practices, which includes advance practice providers typically doing discharge orders for children < 3 months old who only receive acetaminophen for post-operative pain control. Our follow-up calls data is limited by possible selection bias as parents occupied caring for their children in active pain may be less likely to answer the phone or may be more interested in talking to a healthcare provider. Our follow-up ER visit and clinic visits are limited to those that visited providers included in our electronic medical record network of providers. A major advantage of this study is the use of the ePMDP data to verify which patients filled their opioid prescriptions, however, given that patients with filled prescriptions may not take any doses the rates of adverse effects may be higher than reported.14

Our study suggest non-opioid medications are equally effective in controlling post-operative pain after pediatric herniorrhaphy compared to opioid medications. Routine opioid administration does not appear to positively affect postoperative pain management in this population and is associated with a higher rate of medication related side effects. Standard practice at our institution in weight based acetaminophen and ibuprofen alternating every three hours. We hope this data serves as evidence to counsel parents and providers that opioid medications are not necessary. In fact, our study suggests that opioid prescriptions are more likely to cause harm in the form of worsened nausea and vomiting than provide improved pain control.

References

- Brown R, Fortier MA, Zolghadr S, Gulur P, Jenkins BN, Kain ZN. Postoperative Pain Management in Children of Hispanic Origin: A Descriptive Cohort Study. Anesth Analg. 2016;122(2):497-502.

- Rony RY, Fortier MA, Chorney JM, Perret D, Kain ZN. Parental postoperative pain management: attitudes, assessment, and management. Pediatrics. 2010;125(6):e1372-8.

- Hegarty M, Calder A, Davies K, et al. Does take-home analgesia improve postoperative pain after elective day case surgery? A comparison of hospital vs parent-supplied analgesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23(5):385-9.

- Chung CP, Callahan ST, Cooper WO, et al. Outpatient Opioid Prescriptions for Children and Opioid-Related Adverse Events. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2).

- Poonai N, Datoo N, Ali S, et al. Oral morphine versus ibuprofen administered at home for postoperative orthopedic pain in children: a randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2017;189(40):E1252-E1258.

- Kelly LE, Sommer DD, Ramakrishna J, et al. Morphine or Ibuprofen for post-tonsillectomy analgesia: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2015;135(2):307-13.

- Hill MV, Stucke RS, Billmeier SE, Kelly JL, Barth RJ. Guideline for Discharge Opioid Prescriptions after Inpatient General Surgical Procedures. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;226(6):996-1003.

- Overton HN, Hanna MN, Bruhn WE, et al. Opioid-Prescribing Guidelines for Common Surgical Procedures: An Expert Panel Consensus. J Am Coll Surg. 2018;227(4):411-418.

- “Postoperative Opioid Prescribing.” Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative, 27 Sept. 2018, msqc.org/transforming-surgical-care-michigan.

- Cartmill RS, Yang DY, Fernandes-taylor S, Kohler JE. National variation in opioid prescribing after pediatric umbilical hernia repair. Surgery. 2018.

- Blay E, Nooromid MJ, Bilimoria KY, et al. Variation in post-discharge opioid prescriptions among members of a surgical team. Am J Surg. 2018;216(1):25-30.

- Poonai N, Bhullar G, Lin K, et al. Oral administration of morphine versus ibuprofen to manage postfracture pain in children: a randomized trial. CMAJ. 2014;186(18):1358-63.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318(17):1661-1667.

- Wisconsin Department of Safety and Professional Services. “Welcome - Wisconsin Prescription Drug Monitoring Program.” Wisconsin Perscriptions Drug Monitoring Program, pdmp.wi.gov/.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26184/292-wilkinson.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse3

Joseph Pease, Nazrul Islam, Thazin Wynn & Anna Lipp

Norfolk and Norwich University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust

Corresponding author: Dr Joseph Pease, Academic FY2 doctor at Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital

Email: joseph.pease@nnuh.nhs.uk

Key words: diabetes, hypertension, referral, elective surgery

Abstract

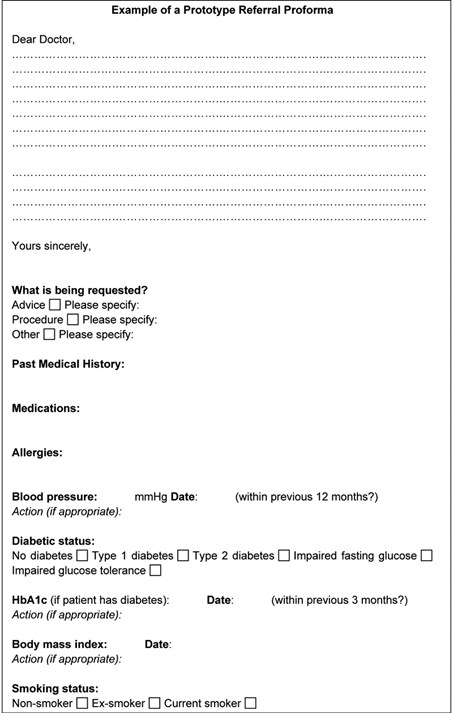

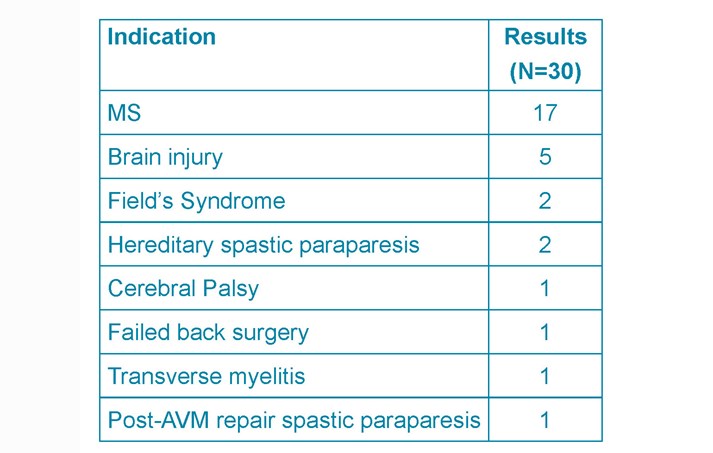

Objectives: Updated guidelines for the peri-operative management of patients with diabetes and hypertension were recently published, and suggest primary care referrals to surgery should include information regarding patients’ diabetic control (glycated haemoglobin - HbA1c) and blood pressure. This allows optimisation of glycaemic control and blood pressure before surgery to reduce the risk of complications, prolonged hospital stay and procedure cancellation; which impacts the patient’s physical and mental health, and has significant financial implications. This audit aims to assess whether surgical referrals from primary care are including this information, and to identify if certain referral formats include them more consistently.

Method: Data including diabetic status, glycated haemoglobin and blood pressure readings were collected from routine referrals between January-February 2017; encompassing 200 adult patients from breast, urology, general and vascular surgery. The number of referrals including this information was calculated, as well as whether they were within guideline limits. Results: 185 referrals contained information on comorbidities, of which 19 patients had diabetes, 3 of whom had accompanying HbA1c levels. Of the 57 patients with hypertension: 49 referrals included a blood pressure measurement, with 6 patients above the advised range.

Conclusions: Few referral letters provided sufficient information recommended by guidelines. Better reporting of HbA1c levels is necessary. Blood pressure, body mass index and smoking status was reported more often, however not consistently. Referrals with electronic summaries were most likely to contain the necessary information. A standardised proforma for elective referrals may be useful in ensuring that relevant information is included. It may be the case that the new guidelines are not yet fully integrated within primary care.

Introduction

In an increasingly burdened National Health Service (NHS), it is essential that things go right first time, with as few interruptions or complications as possible. Referrals for elective surgical procedures from primary care providers should contain sufficient information to initiate the decision-making process for surgeons and anaesthetists for how suitable a patient is for an operation. Guidelines exist with recommendations for optimisation of the patient’s health prior to routine surgery, particularly with regard to glycaemic control and blood pressure (BP). Referral letters are therefore pivotal in influencing the management of surgical patients, yet there is considerable variability in format and content. Including the recommended information may trigger a chain of events, which may ultimately help to reduce the risk of complications, mortality, prolonged hospital stay or postponed procedures. This has wide implications affecting both the patient and the NHS. This audit aimed to identify how many primary care referrals for routine operations included the recommended information about two important perioperative considerations – glycaemic control and BP. It also aimed to identify any effective proformas or referral formats that consistently include this information.

10-15% of patients undergoing surgery have diabetes, and these patients are at greater risk of complications, mortality and extended hospital admission.1 It is therefore imperative that glycaemic control is optimised prior to elective surgery, ideally before referral. Updated guidelines for the perioperative management of patients with diabetes were published in 2015, stating that primary care referrals should contain information about the duration, type of diabetes, current treatment and complications. Additionally, the National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend that referrals should contain the patient’s most recent HbA1c, and that all patients with diabetes should be offered HbA1c testing if they have not been tested within the past 3 months.2 Glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) is widely used as a marker of glycaemic control. Elevated HbA1c levels has been found to be associated with an increased rate of mortality in cardiac surgical patients, and is also with a greater risk of complications and infections.4,5 Since 2012, guidelines have suggested that elective procedures should be postponed if the patient’s HbA1c is ≥69mmol/mol to minimise the risk of these adverse events.3 With these guidelines in mind, primary care referral letters for elective procedures provide key indicators about diabetic control and have the potential to improve glycaemic control at an earlier and more convenient stage for both the patient and the perioperative team.

Hypertension has been shown to be the most common medical cause for postponing surgery.6,7 It is recognised as a significant risk factor in the development of cardiovascular disease and also poses difficulties for the anaesthetist during the perioperative period.7 Patients referred for elective surgery with a BP measurement ≥160/100mmHg in primary care should have their operation postponed until it has been reduced.7

There is no standardised way of referring patients for elective surgical procedures from primary care. A variety of referral formats are used, and are often a combination of letters and a summary of the patient’s healthcare record. However, the content of referral letters is largely down to the individual clinician’s discretion, which varies between clinicians and practices.

Audit Objectives

- To determine whether primary care referral letters contain sufficient information about diabetic control, BP and other clinical information relevant for elective operations

- To examine which referral formats consistently include sufficient information about relative aspects of a patients medical history

Assessing the strengths and weaknesses of the current referral systems allows for identification of ways to improve and streamline the elective surgery pathway for patients, maximising the opportunity for day surgery and hopefully reducing the risk of complications.

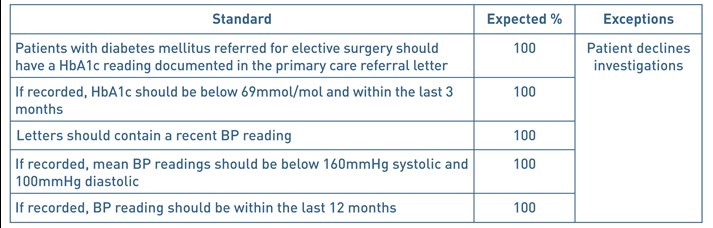

The following standards were therefore devised:

Table 1. Audit standards

Methods

Inclusion criteria: referrals for adult patients (aged 18 years and above) from primary care to urology, general, breast or vascular surgery under a ‘routine’ referral pathway July 2016 to March 2017.

Exclusion Criteria: patients referred under ‘2 week wait’ or ‘urgent’ referral pathways. Patients aged under 18 years old. Patients referred and subsequently redirected to a non-surgical specialty.

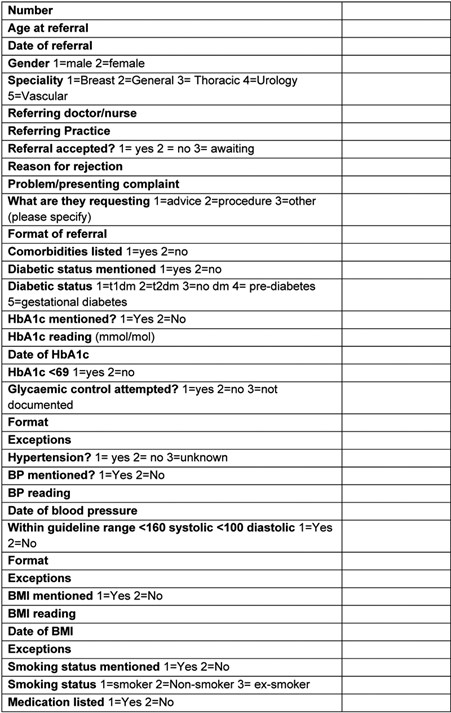

Referrals arranged in descending chronological order were accessed using an electronic Outpatient Referral system. The 50 most recent routine referrals were accessed for each of the following surgical specialties: general surgery, urology, breast surgery and vascular surgery. Anonymised data was recorded onto a data collection sheet on Microsoft Excel (see appendix 1) on a password-protected computer.

Article continues after ad.

Results

Information from 200 referrals was obtained, consisting of 112 women and 88 men, ranging from 18 to 96 years old. No exceptions were found. 148 of the 200 referrals were requesting advice on further management or a review of the patient and 44 referrals were directly requesting a procedure or operation. 8 referrals were either requesting both advice and a procedure, or were concerning other matters.

19 patients were stated as having diabetes within the referral letter or accompanying electronic summary. 18 of these had type 2 diabetes and one patient had type 1. 5 patients had ‘prediabetes’. 161 patients were presumed to be non-diabetic as there was no diagnosis of diabetes listed and there was insufficient clinical information to determine if the remaining 15 patients were diabetic or not. Of the 19 referrals of patients with diabetes, 3 (15.8%) of these included a HbA1c reading. 5 non-diabetic patient referrals also had an accompanying HbA1c reading. All 8 of these readings were below 69mmol/mol. 2 were taken within 3 months. 1 HbA1c reading was recorded 3 months and 1 day before the date of referral.

57 patients had a diagnosis of hypertension that was apparent within the referral letter. 132 patients had no listed diagnosis of hypertension and it was unclear whether the remaining 11 patients had hypertension or not.

Just under half of all referrals (96/200) included a BP measurement. Of these, 90 patients had a BP reading less than 160/100mmHg. 8 patients had a BP reading ≥160/100mmHg, 6 of these were known to have hypertension. For patients with known hypertension, 49 of 57 (86%) referrals included a BP reading. 69/96 (72%) readings were taken within the last 12 months. 23 were older than 12 months, and 4 were not clearly dated.

The most widely used referral format was a letter with an accompanying patient healthcare summary, with 79 of the 200 referrals being made this way. The second most commonly used format was a letter alone, either electronic or printed, which comprised 51 referrals. All 50 breast referrals were made using a local, standardised breast care proforma. The majority of these also included a healthcare summary (37/50). Each format was reviewed to see if it contained both a BP measurement and a HbA1c reading (if appropriate). The referral format that most consistently included both of these values was a letter with an attached healthcare summary (58.23%). The addition of an electronic healthcare summary to a referral letter resulted in almost double the percentage of referrals including the necessary information (29.41% vs 58.23%).

Figure 1. Proportion of referrals containing a BP measurement and a HbA1c value (if appropriate) by format.

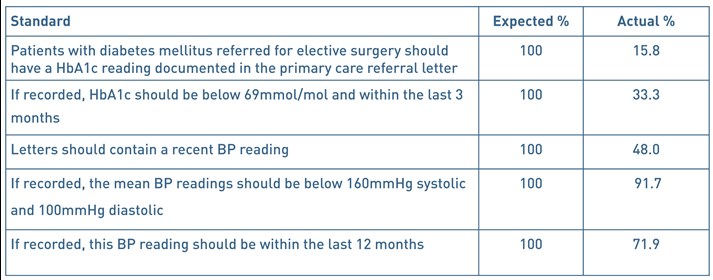

Table 2. Audit Standards and results – summary.

Discussion

19 of the 200 patients had diabetes, which roughly reflects the proportion of surgical patients with diabetes. HbA1c readings were not regularly included in referrals for these patients. This finding impacts the care pathway of this patient as it should be measured prior to pre-operative assessment. This may incur delays for the patient if it is found to be above 69mmol/mol, and could result in inefficient use of resources and clinic time due to an inappropriate referral. Alternatively, if the operation goes ahead, it would be subjecting the patient to risks associated with suboptimal glycaemic control. Whilst it is likely that HbA1c monitoring is taking place, either in primary or secondary care, such information may not be readily available.

96 of the 200 referrals (48%) contained a BP reading. However, if the patient was known to have hypertension, then the proportion of referrals containing a BP reading was 86%, showing that general practitioners (GPs) recognise the perioperative importance of including a BP reading when referring the patient if it is known to be high. Of the 148 patients referred for advice/review only, 68 (45.95%) of these referrals included a BP reading. When compared to the 44 patients referred specifically for a procedure, 25 (56.82%) included a BP reading. This may suggest that GPs are more vigilant with blood pressure documentation when they know that the patient is more likely to have an operation.

This audit has demonstrated the variety of referral formats that are used by primary care. With the exception of breast services, there is currently no set proforma for referring patients to a surgical specialty. The format that most reliably included the necessary information was a letter with attached healthcare summary, but there were still many referrals using this format that did not include information about blood pressure or HbA1c. Including a healthcare summary of the patient within the referral did improve the rates of documented BP measurements and other important factors, so it is worth appreciating the benefits of attaching these summaries. Whilst most aspects of a patient’s healthcare record can be obtained by secondary care, this is an avoidable use of time and resources. There was a relatively small number of patients with diabetes used in this audit as there was no practical way of identifying only diabetic patients using the software available. Perhaps an audit exclusively assessing patients with diabetes would be more useful.

Not all patients referred to secondary care by GPs were for a definitive surgical procedure, with the majority of patients being referred for review or advice. Whilst it is unknown whether these patients ultimately had an operation, it might still influence the content of the referral letter if the GP believes that the patient will be undergoing an operation. This issue could be addressed in future audits by only selecting referrals where a specific operation is requested. However, being able to compare the content of referrals requesting advice in contrast to those requesting a specific procedure is useful.

The variability in content and format of surgical referral letters highlights the problem that recommended information can be missed. Although further studies are needed to fully elucidate the impact of not including such information, for example, rates of postponed operations or unplanned admission after day surgery, it is a logical step to find ways to ensure that all referrals contain the necessary data. Additionally, this audit suggests that more work is needed to ensure that perioperative guidelines are better integrated into primary care. A follow-up survey of primary care providers would be useful to ascertain the awareness of these.

Elective surgical referrals may also provide a chance to opportunistically motivate and educate patients on managing their health, with the shared goal of undergoing a procedure as safely as possible. It could provide an indication of the ongoing management of chronic conditions such as diabetes and hypertension. Therefore, the benefits of a well-completed referral letter are not limited to the anaesthetist, but are advantageous to the GP and patient as well.

We suggest the referral process could be improved by implementing an electronic proforma, to ensure that these key clinical variables are included (example in appendix 1). Alternatively, this could be incorporated into the primary care software systems as a prompt or automated message when beginning to write a referral with a checklist of key questions pertinent to each of the patient’s conditions.

Ultimately, including the appropriate information in every referral letter is a relatively quick and simple process, and could help improve the standard of care provided to patients.

Acknowledgements

Tahlia Collins – audit facilitator

Declaration of Interests

None declared from any of the authors

References

- Barker P, Creasy PE, Dhatariya K, Levy N, Lipp A. Peri-operative management of the surgical patient with diabetes. Anaesthesia 2015. doi:10.1111/anae.13233

- National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (2016). Preoperative tests (update) – Routine preoperative tests for elective surgery. NICE Guideline (NG45).

- Dhatariya K et al. NHS Diabetes guideline for the perioperative management of the adult patient with diabetes. Diabet Med. 2012 Apr;29(4):420-33. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03582.x.

- Aldam P, Levy N, Hall GM. Perioperative management of diabetic patients: new controversies. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2014; 113(6):906-909. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu259

- Sato H, Carvalho G, Sato T, Lattermann R, Matsukawa T, Schricker T. The Association of Preoperative Glycemic Control, Intraoperative Insulin Sensitivity, and Outcomes after Cardiac Surgery. The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 2010; 95(9): 4338-4344.

- Dix P, Howell S. Survey of cancellation rate of hypertensive patients undergoing anaesthesia and elective surgery. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2001; 86(6):789-793.

- Hartle A et al. The measurement of adult blood pressure and management of hypertension before elective surgery. Anaesthesia 2016; 71:326-337. doi:10.1111/anae.13348

Figure 2. Questions from the data collection sheet

Example of a prototype referral proforma.

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26188/292-pease.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse4

Sherif Monib1, Andrew Ritchie1 Ahmed Hamad2, & Mohamed Elbeshlawy3

1 General Surgery Department, West Hertfordshire Trust, Hertfordshire, UK.

2 General Surgery Department, The Heart of England Trust, Birmingham, UK.

3 Gastroenterology Department, Mouwasat Hospital, Qatif, Saudi Arabia.

Corresponding author: Sherif Monib MSC MRCS FEBS Email: sherif.monib@whht.nhs.uk

Ethical Approval

No ethical approval was needed for this study as it is a retrospective analysis of slandered practice

Patient’s consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to include images in the article.

Abstract

Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) has gained wide acceptance as a relatively safe and efficient method for long-term enteral nutrition. A rather unusual complication of PEG is the buried bumper syndrome (BBS) which was first reported in 1988. A buried bumper is associated with very serious complications, such as perforation of the stomach, peritonitis and in reported cases, death.

Endoscopic methods such as the needle knife technique and the push-pull T-technique have been described, but these both require advanced endoscopic skills and are often unsuccessful. Subsequently, the buried inner bumpers are removed surgically, either by making an external incision over the PEG site under local anesthesia or at laparotomy. These approaches can be associated with pain, wound infection, or a gastro-cutaneous fistula. External traction has been suggested. However, this can cause an enormous shearing force and may result in tearing at the PEG site.

We describe the Water Jet technique, a novel method to manage a BBS. It requires simple general endoscopic skills and materials that are readily available at the endoscopy suite or operating room.

We believe this technique has a valid role to play in the management of this condition reducing the need for surgery and also improving patient’s outcome.

Keywords: PEG, Buried bumper syndrome, Water jet.

Introduction

We describe the Water Jet technique, a novel method to manage a BBS. It requires simple general endoscopic skills and materials that are readily available at the endoscopy suite or operating room.

We believe this technique has a valid role to play in the management of this condition reducing the need for surgery and also improving patient’s outcome.

Methods

With the old Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tube kept in place, a Computer tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis is carried out to rule out anterior abdominal wall collection or intraperitoneal sepsis.

If there is no intraperitoneal sepsis, the patient is then prepared for endoscopy which is usually done by the endoscopist in the endoscopy unit with a surgeon ready with a minor set.

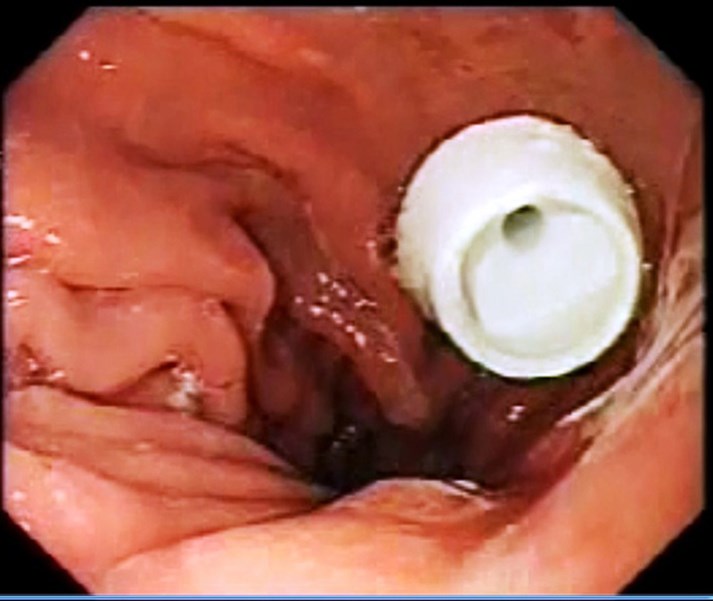

Intravenous antibiotic is given before starting the procedure, with the patient sedated, the abdomen is painted with antiseptic solution and draped, local anesthetic is infiltrated around the PEG tube, endoscopy is carried out, gastrostomy is identified if possible (Fig1), if not, normal saline is injected by the surgeon through the PEG tube and the gastrostomy is identified (Fig 2), the guide wire is passed by the surgeon through the old PEG tube which might need to be shortened. The guide wire is then visualized in the stomach and pulled by the endoscopist (Fig 3) who attaches it to the distal end of a new PEG tube. The surgeon pulls the wire back pulling the new PEG tube which will now replace the old PEG tube which will not be discarded. (Fig4). The team should keep in mind not to put too much pressure on the gastric wall. The PEG tube new is fixed in the usual way.

Figure 1: Endoscopic view identifying the gastrostomy.

Figure 2: Endoscopic view delineating Injection of normal saline by the surgeon through the PEG tube to aid identification of the gastrostomy.

Figure 3: Visualization of the gastrostomy by the endoscopist.

Figure 4: The surgeon pulls the wire back and the old PEG tube is replaced by a new one.

Discussion

PEG has gained wide acceptance as a relatively safe and efficient method for long-term enteral nutrition. A rather unusual complication of PEG is the buried bumper syndrome (BBS) which was first reported in 1988 and described by Klein et al in 1990.[1-3] It is believed to occur in 0.3 – 2.4 % of patients.[4] Excessive tension, leading to ischemia of the mucosa sandwiched between the inner and outer bumpers causes ulceration at the bumper site.[5] The internal bumper becomes lodged along the gastrostomy tract between the gastric wall and skin. Subsequent healing causes overgrowth of gastric mucosa over the inner bumper of the tube leading to mechanical failure of feed delivery, rendering the tube useless. Presenting features1990; 85:448bumper syndrome can include peritubular leakage, occlusion of PEG feeding, external stoma skin erythema or induration, or abdominal pain. [6-13] A buried bumper is associated with very serious complications, such as perforation of the stomach, peritonitis and in reported cases, death.[14]

There are various internal and external techniques for removal of the buried bumper described in the literature. There are a number of known endoscopic techniques. Firstly, the use of needle knife papillotome to expose the internal bumper followed by retrieval with an endoscopic snare after external cutting of the PEG tube.[15,16,17] Secondly, the push and pull “T” technique with a tube fragment grasped by a snare.[18] Thirdly, extraction using the tapered tip of a new PEG tube or extraction using Savary dilator over a guide wire to push the PEG tube towards the lumen of the stomach.[19,20] Finally, an oesophageal balloon dilator is maximally inflated while it is in the tube to make extraction through the stomach possible.[21]

Additionally, successful simple external traction removal was reported with certain externally removable PEG tubes as they have a soft collapsible internal bumper.[21,23] A radiological technique removing the buried bumper was recently described using an angioplasty balloon dilator and radiological guidance.[24] Surgical treatment is required in some cases by mini-laparotomy or a laparoscopic approach.[8,25]

Conclusion

Water Jet technique is a safe easy technique which can be used use for management of cases of BBS not complicated by intra-abdominal sepsis

References

- Shallman RW, Norfleet RG, Hardache JM. Percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy feeding tube migration and impaction in the abdominal wall. Gastrointest Endosc 1988; 34 367–68.

- Gluck M, Levant JA, Drennan F. Retraction of Sacks-Vine gastrostomy tubes into the gastric wall: a report of seven cases. Gastrointest Endosc 1988; 34 215.

- Klein S, Heare BR, Soloway RD. The ?buried bumper syndrome?: a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1990; 5: 448-51.

- Venu RP, Brown RD. Pastika BJ Erickson LW. The buried bumper syndrome: a simple management approach in two patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 582-584.

- E. Leung, L. Chung, A. Hamouda and A. H. M. Nassar: A new endoscopic technique for the buried bumper syndrome. Surgical Endoscopy Volume 21, Number 9, 1671-1673, DOI: 10.1007/s00464-007-9224-x

- Schwartz HI, Goldberg RI, Barkin JS, Phil lips RS, Land A, Hecht M. PEG feeding tube migration impaction in the abdominal wall. Gastrointest Endosc 1988;35:134.

- Gluck M, Lev ant JA, Drennan F. Retraction of Sacks-Vine gastrostomy tube into the gastric wall: report of seven cases. Gastrointest Endosc 1988;34:215.

- Kaplan DS, Fried MW: Migration of PEG tubes. Am J Gastroenterol 1989;84:1590-1.

- Klein S, Heare BR, Soloway RD. The “Buried Bumper Syndrome”: a complication of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Am J Gastroenterol 1990;85:448-51.

- Patel PH, Hunter W, Willis M. Upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage secondary to gastric ulcer complicating percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy. Gastrointest Endosc 1988; 34:288.

- Nelson AM. PEG feeding tube migration and erosion into the abdominal wall. Gastrointest Endosc 1989;35: 133.

- Lee MP. Impaction of gastrostomy tube in the abdominal wall. J Am Geriatr Soc 1990;38:956.

- Boyd JW, Delegge MH, Shamburek RD. The buried bumper syndrome: a new technique for safe, endoscopic PEG removal. Gastrointest Endosc 1995;41:508-11.

- Anagnostopoulos GK, Kostopoulos P, Arvanitidis DM. Buried bumper syndrome with a fatal outcome, presenting early as gastrointestinal bleeding after percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy placement. J Postgrad Med 2003; 49: 325-7.

- Braden B, Brandstaetter M, Caspary WF, Seifert H. Buried bumper syndrome: treatment guided by catheter probe US. Gastrointest Endosc 2003; 57: 747-751.

- Charles KF. Buried bumper syndrome: Old problem, new tricks. J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2002; 17: 1125-1128.

- Ma MM, Semlacher EA, Fedorak RN, Lalor EA, Duerksen DR, Sherbaniuk RW, Chalpelsky CE, Sadowski DC. The buried gastrostomy bumper syndrome: prevention and endoscopic approaches to removal. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41: 505-508.

- Boyd JW, DeLegge MH, Shamburek RD, Kirby DF. The buried bumper syndrome: a new technique for safe endoscopic PEG removal. Gastrointest Endosc 1995; 41: 508-511.

- Venu RP, Brown RD. Pastika BJ Erickson LW. The buried bumper syndrome: a simple management approach in two patients. Gastrointest Endosc 2002; 56: 582-584.

- Reider B, Pfeiffer A. Endoscopic treatment of the buried bumper syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc 2005; 61(5): AB180.

- Strock P, Weber J. Buried bumper syndrome: endoscopic management using a balloon dilator. Endoscopy 2005; 37: 279.

- Frascio F, Giacosa A, Piero P, Sukkar SG, Pugliese V, Munizzi F. Another approach to the buried bumper syndrome. Gastrointest Endosc 1996; 43: 263.

- Lu RG, Koc D, Tozun N. The buried bumper syndrome: migration of internal bumper of percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube into the abdominal wall. Gastroenterology 2003; 38:1077-1080.

- Crowley JJ, Vora D, Becker CJ, Harris LS. Radiologic removal of buried gastrostomy bumpers in paediatric patients. Am J Roentgenol 2001; 176: 766-768.

- Boreham B, Ammori BJ. Laparoscopic percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy removal in a patient with buried bumper syndrome: a new approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2002; 12: 356-358

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26186/292-monib.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse5

Jacob Gluyas, Medical Student1, Mr Ramiz Ziyara, Senior Clinical Fellow, Vascular Surgery2, Mr John Quarmby, Consultant General, Vascular and Paediatric Surgeon2

1University of Nottingham 2Department of Vascular Surgery, Royal Derby Hospital, Derby, Derbyshire, DE22 3NE, UK

Keywords: Training, education, surgical training, core trainee, day-case surgery, general surgery, vascular surgery

Abstract

Introduction: Trainees receive a variable exposure to surgical cases across UK hospital trusts which does not necessarily fulfil the requirements of the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Program. Previous audits at this unit highlighted training opportunities in Day-Case Surgical Units (DCU) were not being utilised for training.

The aim was to Re-audit DCU to quantify current trainee participation in day-case surgery at the Royal Derby Hospital and ascertain whether the previous audit had any impact on trainee participation.

Methods: All General and Vascular DCU surgical cases performed at the Royal Derby Hospital between 01-Dec-16 to 30-Nov-17 we reviewed by examining Operative Room Management Information System (ORMIS) case records. Each case was classified as consultant operating solo, trainees assisting or trainees as lead surgeon.

Staff grade surgeons were included and classified depending on their role: as ‘consultant’ when operating on a list as the named surgeon and ‘trainee’ when assisting on another consultant’s list.

Results: 623 lists were audited, with 1754 cases performed. Trainees attended 763 cases (43.5%) and were lead surgeon in 104 cases (5.9%).

The 2010/11 audit included 1672 cases. Trainees attended 434 cases (26.0%) and led on 47 (2.8%).

Conclusion: Trainee attendance in DCU has increased in the 6-year interim period. Trainees are still absent from the majority of lists (56.5%) in DCU and as such are still missing out on valuable training opportunities. More options need to be explored to make best use of these opportunities. Rota coordinators need to ensure that day-case unit surgery is included in lists.

Introduction

The core requirement of surgical competency and proficiency is acquisition of technical skills, which can only be achieved by supervised repetition in the operating theatre environment. This takes time, which is a commodity that all trainees have seen progressively cut-back over the past three decades. Trusts have been made to alter working patterns and curb maximum hours worked in a week in response to various enquiries, and complex rotas have been implemented to adhere to the European Working Time Directive. This is compounded by surgical trainees being shouldered with additional non-operative demands as part of their day to day work. The sum of all these features is a demonstrable reduction in operative training received (1).

While quantity of procedures witnessed does not necessarily correlate directly with a technical skill acquisition and surgical competency, as with any skill, repetition is the key to success. Time spent performing surgery is key to surgical competency and attendance to cases is used as part of the criteria outlined in the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Program (ICSP) to measure completion of training (2). The reduction in hours worked, both overall and time spent operating, has led to a wide variation in the volume of surgery that trainees are exposed to across UK hospital trusts (3,4), and in up to 33% of cases CCTs are being awarded to surgeons who have not achieved the indicative total operative experience as set out in the ICSP guidelines (3).

This trust has previously audited (5) and highlighted training opportunities in Day-Case Surgical Units (DCU) across all general surgical procedures that are not being utilised by surgical trainees. This piece was written following a re-audit across the same time period 6 years later. The findings of the original 2010/11 audit were communicated to the surgical teams at the time with the aim that they would prompt changes to rota allocations to improve trainee attendance at day case. The goal of the 2016/17 repeat audit was to identify whether previous audit findings have had an impact on trainee attendance at day-case surgery by quantifying current trainee participation in day-case surgery at the Royal Derby Hospital.

Methods

All General and Vascular surgical cases performed at the Royal Derby Hospital day-case surgical unit between 01-Dec-16 to 30-Nov-17 were reviewed. Reporting was conducted by examining Operative Room Management Information System (ORMIS) case records. Data was collected on whether consultants were operating solo, trainees were assistant surgeons, or whether trainees were lead surgeon on cases. We defined the lead surgeon as being the individual named as ‘surgeon 1’ in ORMIS, with subsequent ‘surgeon 2/3’ being listed as assisting surgeons.

‘Trainee surgeons’ were classified as any surgeon operating below consultant grade. Staff grade surgeons were included in the audit and were classified depending on the role they were performing: classified as ‘consultant’ when operating on a list where they were the named surgeon, classified as ‘trainee’ when assisting on another consultant’s list. This classification was to reflect the purpose of their attendance.

One flaw in our audit methodology was identified during the preparation of this piece for presentation; the reliance on entries in ORMIS to base conclusions on. In light of this it was decided a small sub-audit would be performed to quantify the discrepancy between ORMIS and operation notes. Twenty cases were audited across a two-week period in May-18 and results from ORMIS and the operative note entry compared.

Results

There were a total of 623 surgical lists, with 1754 cases performed. Of these, 1753 met the inclusion criteria; a single case was excluded on the basis it was a non-surgical case. Of the 1753 cases, trainees attended 763 (43.5%), and were the lead surgeon in 104 (5.9%) cases.

The previous 2010/11 audit found a total of 1672 applicable cases were performed. Trainees attended 434 (26.0%) of the 1672 cases and led only 47 (2.8%) of them.

Findings from the sub-audit showed that of the 20 cases performed, ORMIS notes reported trainees participated in 8 of the cases (40%) of cases compared to 10 cases (50%) as per patient notes. Most importantly, the operative notes indicated 7 of the cases (35%) were either led or performed jointly between consultant and trainee, compared to a reported 0% on ORMIS across the same period.

Conclusion & discussion

The Royal Derby Hospital (RDH) surgical teams have taken the approach that with increasing limitations being placed on both junior and consultant grades, the best way to optimise training is by increasing quantity of exposure. Day-case surgery is perfectly tailored to do this: high-volume case loads of routine procedures ideal for trainees to develop their surgical skills and knowledge of surgical practices while under senior supervision. For these reasons it was targeted as part the auditing process and results indicate that change has been made in the 6-year interim period resulting in better use of the training opportunities available in DCU. Trainee participation has risen from 26% to 43.5%, with the number of trainee led cases more than doubling from 47 in 2010/11 to 104 in 2016/17 (2.8% to 5.9% respectively). However, trainees are still absent from the majority of lists (56.5%) performed in DCU suggesting that junior surgeons are still missing out on valuable training opportunities at RDH. More options need to be explored to make best use of these opportunities for the next generation of doctors to enter surgical training. Several changes have been proposed, one such being the creation of a dedicated DCU core trainee grade position at RDH, giving an individual(s) protected time to develop operative skills and an exposure to surgery above and beyond that which they would be able to achieve in any other core trainee role.

Other trusts have suggested that the focus should be on quality of exposure, rather than quantity of surgical experience. The University Hospital of South Manchester (UHSM) ran one of sixteen Better Training Better Care (BTBC) pilots as supported by Health Education England (HEE) across 2012-2014 (6). The BTBC initiative was based on key recommendations from Sir John Temple’s Time for Training (7) and Professor John Collins’ Foundation for Excellence (8). In this pilot scheme, consultants were asked to protect a portion of their operating lists (approximately one eighth) for core surgical trainees (CST)s. Each ‘BTBC list’ was trainee-led from admission to discharge with consultant supervision throughout. The CST saw and examined the patient at admission, completed pre-operative work, took charge of the team brief and World Health Organisation (WHO) checklist before starting surgery and finally conducted the surgery under supervision. There were no findings suggesting that patient care had been compromised on CST lists, nor was there any change in patient satisfaction. Unsurprisingly, mean operating time was slightly increased in the trainee vs. consultant-led lists groups. As a consequence of the dedicated lists, there was a reduction in the number of cases that core trainees assisted consultants on i.e. inclusion of the ‘high-quality’ dedicated lists had reduced overall surgical exposure by the trainees. Ratings from core trainees that took part was that the protected lists were very beneficial to training (rated using a modified mini Surgical Theatre Educational Environmental Measure, mini STEEM), despite the reduction in overall surgical exposure.

When comparing the approach of each study to the ISCP guidelines, both clearly improve the ability of trainees to achieve the recommended criteria either by improving acquisition of skills or by exposure to surgery. Attending more surgical cases undoubtedly benefits trainees, though without an objectifiable measure it is difficult to discern the degree of benefit increased attendance has compared to protected training lists dedicated to the learning of the trainee. One of the most obvious benefits of increasing attendance to surgery over providing dedicated lists is the minimal impact on service provision. The Manchester BTBC study showed a slight increase in time taken to complete operations in the trainee led lists (89 mins compared to 74 mins for an open inguinal repair). Should this approach be utilised in at the RDH, one way around this problem would be to ensure the training lists were those with fewer cases on. This would minimise the potential for disruption to services.

As discussed in the methodology, reliance on entries in ORMIS was identified as a potentially major flaw in the study. There is no guidance on how to populate the data fields in ORMIS, which role the surgeons participating in should be listed under or whether the entries ‘surgeon 1’ and ‘surgeon 2’ accurately reflect the role each was taking in the surgery. Anecdotal evidence showed a great degree of variation with how entries were added, with some staff simply recording the list’s consultant as lead surgeon in all cases. The consensus was that patient records and operation notes would be a better source of information and would be more likely to be accurate than the ORMIS entry. This potential problem was only identified after the initial audit had been completed. It was agreed by all parties that with the resource available, retrospectively working through 1754 patient files was not feasible in the timeframe given and may even have been impossible to complete. With more time and resource this would have been the best way to obtain accurate information regarding trainee participation.

It was decided a sub-audit should be performed to investigate the potential discrepancy between ORMIS and case-notes. This resulted in a number of inaccuracies being identified: of the 20 cases examined, ORMIS had trainee participation recorded in 8 cases (40%) compared to 10 (50%) as recorded in the patient notes. More importantly however, the operative notes indicated a significantly higher proportion of trainees took a more active role in the surgery, with 7 cases (35%) either led by trainees or performed jointly between consultant and trainee, compared to a reported 0% on ORMIS. These findings suggest that the initial audit may have slightly under-represented actual trainee participation but appears to be largely accurate. It does imply that trainees are more involved and may be gaining more benefit from the surgeries they attend, compared to the initial audit findings.

The findings of the audit need to be interpreted in light of the premise of this audit; that DCU could providing opportunities to help trainees meet the required case-load defined by the Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Program. The information from the audit is limited in that it simply looked at all procedures performed by general surgeons; there was no categorisation into sub-specialties, type or complexity of procedure. It was designed to simply look at trainee presence in day-case surgery and whether day-case was being best used to help training surgeons obtain adequate exposure to surgery. The DCU was chosen as the focus of the audit as it was agreed by the senior consultant team that should change be implemented (be it DCU core training roles, dedicated training lists or another intervention), it offered the best balance between suitably complex procedures while minimising impact on service provision. This view was taken as the complexity of the majority of cases undertaken in DCU have a limited scope for over-running compared to main theatre lists.

Before implementing any change, future work may need to investigate the types of cases performed and categorising them based on difficulty/complexity to better identify those that would be suitable for a given level of surgeon. This needs to be cross referenced against trainee experiences in surgery. Methods for doing this are variable but specifically they need to ask trainees to answer the question “what is the best way to improve your experience and facilitate skill acquisition”? Suggestions for how to go about doing this include simple measures such as trainee experience surveys or log book auditing. This would then be able to guide whether further work needs to be done to simply rota trainees into day-case surgery or if indeed an alternative approach is required.

Prior to repeating the audit process, our recommendation is that a guideline for populating ORMIS should be produced. This will ensure accurate information is recorded consistently which reflects the surgery participants. This will allow future audits to be performed with more ease, more frequently and to generate more meaningful information.

Having demonstrated that trainee participation has increased, more work needs to be done to continue this upwards trajectory, while simultaneously identify how to maximise learning and benefit to trainees with the limited time available. The ultimate goal is for the Royal Derby Hospital to provide the best programme for the next generation of surgeons in training. We hope this audit can provide the basis for realising that goal.

References

- Kara N, Patil PV, Shimi SM. Changes in working patterns hit emergency general surgical training. Ann R Coll Surg Engl (Supp) 2008;90:60-3. [Link]

- Intercollegiate Surgical Curriculum Programme; [Link]

- Charlotte Thomas, Gareth Griffiths, Tarig Abdelrahman, Cristel Santos, Wyn Lewis. Does UK surgical training provide enough experience to meet today’s training requirements? BMJ 2015;350:h2503, 11 May 2015; [Link]

- Improving surgical training report, Royal College of Surgeons; October 2015; [Link]

- Elena Theophilidou, Ahmed El-Sharkawy, J.W. Quarmby. Training in day-case surgery – a missed opportunity; International Journal of Surgery, 2012, Volume 10, Issue 8, Page S76

- Zeiton M, Coe P, Derbyshire L et al. Maximising learning opportunities in the time available for surgical training. Bull R Coll Surg Engl 2016; 98: 418–422. [Link]

- Temple J. Time for Training. May 2010. [Link] [last accessed 26-November-2018]

- Collins J. Foundation for excellence. An evaluation of the Foundation Training Programme. October 2010. [Link] [last accessed 26-November-2018]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26187/292-gluyas.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse6

The Journal of One-Day Surgery considers all articles of relevance to day and short stay surgery. Articles may be in the form of original research, review papers, audits, service improvement reports, case reports, case series, practice development and letters to the editor. Research projects must clearly state that ethics committee approval was sought where appropriate and that patients gave their consent to be included. Patients must not be identifiable unless their written consent has been obtained. If your work was conducted in the UK and you are unsure as to whether it is considered as research requiring approval from an NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC), please consult the NHS Health Research Authority decision tool at http://www.hra-decisiontools.org.uk/ethics/.

Articles should be prepared as Microsoft Word documents with double line spacing and wide margins. Submissions must be sent by email to the address below. A scanned letter requesting publication signed on behalf of all authors must also accompany articles.

Any source of funding should be declared and authors should also disclose any possible conflict of interest that might be relevant to their article.

Title Page

The first page should list all authors (including their first names), their job titles, the hospital(s) or unit(s) from where the work originates and should give a current contact address for the corresponding author.

The author should provide three or four keywords describing their article, which should be as informative as possible.

Abstract

An abstract of 250 words maximum summarising the manuscript should be provided and structured as follows: Introduction, Methods, Results, Conclusions.

Main article structure

Manuscripts should be divided into the following sections: Introduction, Methods, Results, Discussion and References. Tables and figures should follow, with each on a separate page. Each table and figure should be accompanied by a legend that should be sufficiently informative as to allow it to be interpreted without reference to the main text.

All figures and graphs are reformatted to the standard style of the journal. If a manuscript includes such submission, particularly if exported from a spreadsheet (for example Microsoft Excel), a copy of the original data (or numbers) would assist the editorial process.

Copies of original photographs, as a JPEG or TIFF file, should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedding pictures within the text of the manuscript.

Tables, Figures and Graphs:

Please submit any figures, graphs and images as separately attached files rather than embedding non-word files into the word manuscript document. Tables constructed in MS Word can be left in their original MS Word file including the manuscript if this is where they were drawn.

Figures and graphs can be presented in colour but try to avoid 3-d effects, shading etc. Figures and graphs may be redrawn if the quality is not in keeping with the Journal. Please make it clear within the manuscript text where you would like tables, graphs or images to be placed in the finished article with the use of a brief explanatory legend in the manuscript file where you wish the item to be placed, e.g.

Table 1. Patient demographic details.

Figure 1. Proportion of procedures performed as a day-case each year between 2005 and 2018.

Photographs

Photographs can be provided as jpg or tiff files but should be included as a separate enclosure, rather than embedded within the text of the manuscript. This ensures higher quality images. However, we will accept images within Word documents but image quality might suffer!

References

Please follow the Vancouver referencing style:

- References in the reference list should be cited numerically in the order in which they appear in the text using Arabic numerals, e.g. 1, 2, 3, 4 etc.

- The reference list should appear at the end of the paper. Begin your reference list on a new page and title it 'References.'

- Cite articles in the manuscript text using numbers in parentheses and the end of phrases or sentences, e.g. (1,2)

- Abbreviate journal titles in the style used in the NLM Catalogue: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nlmcatalog?Db=journals&Cmd=DetailsSearch&Term=currentlyindexed%5BAll%5D

- The reference list should include all and only those references you have cited in the text. (However, do not include unpublished items such as correspondence).

- Check the reference details against the actual source - you are indicating that you have read a source when you cite it.

- Be consistent with your referencing style across the document.

Example of reference list:

- Ravikumar R, Williams J. The operative management of gallstone ileus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl 2010;92:279–281.

- Dybvig DD, Dybvig M. Det tenkende mennesket. Filosofi- og vitenskapshistorie med vitenskapsteori. 2nd ed. Trondheim: Tapir akademisk forlag; 2003.

- Beizer JL, Timiras ML. Pharmacology and drug management in the elderly. In: Timiras PS, editor. Physiological basis of aging and geriatrics. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 1994. p. 279-84.

- Kwan I, Mapstone J. Visibility aids for pedestrians and cyclists: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Accid Anal Prev. 2004;36(3):305-12.

- Barton CA, McKenzie DP, Walters EH, et al. Interactions between psychosocial problems and management of asthma: who is at risk of dying? J Asthma [serial on the Internet]. 2005 [cited 2005 Jun 30];42(4):249-56. Available from: http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals/.

Submissions are subject to peer review. Proofs will not normally be sent to authors and reprints are not available.

All submissions should be emailed to The Editor: davidbunting@nhs.net

Mr David Bunting

Editor, Journal of One Day Surgery

Consultant Upper GI Surgeon

North Devon District Hospital

[These guidelines were last revised on 05.11.2018]

Download this article as PDF here: https://appconnect.daysurgeryuk.net/media/26181/284-author-guidelines.pdf

Cite this article as: https://bads.co.uk/for-members/journal-of-one-day-surgery-jods/?id=1726#collapse7

Cristina Cernei

Final year medical student at Swansea University Graduate Entry Medicine, Morriston Hospital, Swansea

Keywords: intrathecal, baclofen, morphine, pumps, rate, perioperative

Abstract:

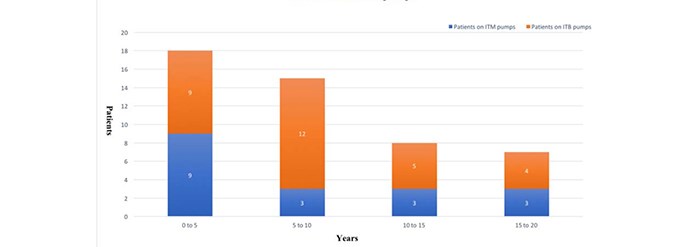

Introduction: Intrathecal baclofen (ITB) and morphine (ITM) pumps improve pain, spasticity and QoL. Pump explanations due to complications are more expensive and traumatic for patients. Determining complication rates is beneficial from a bio-psychosocial aspect.

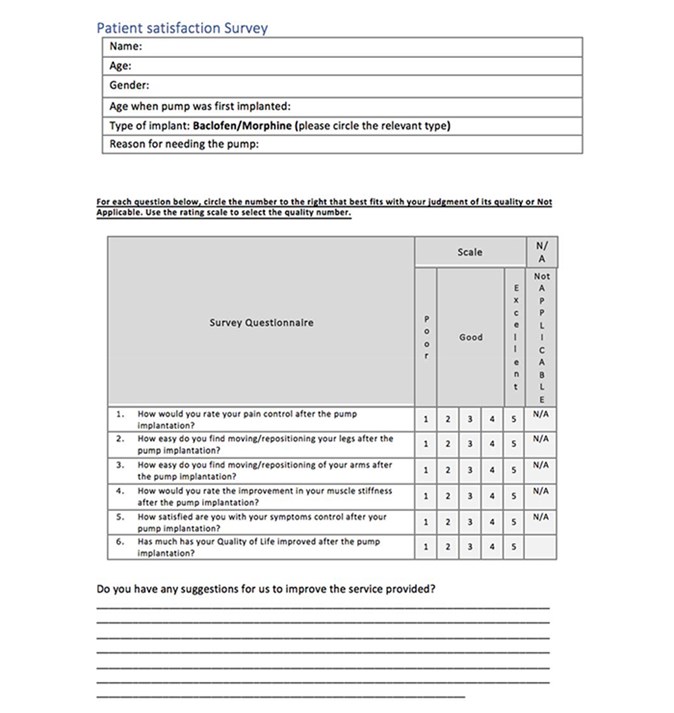

Aims: Determine the perioperative complications post-primary pump implantation (1998-2016); perform a service evaluation.

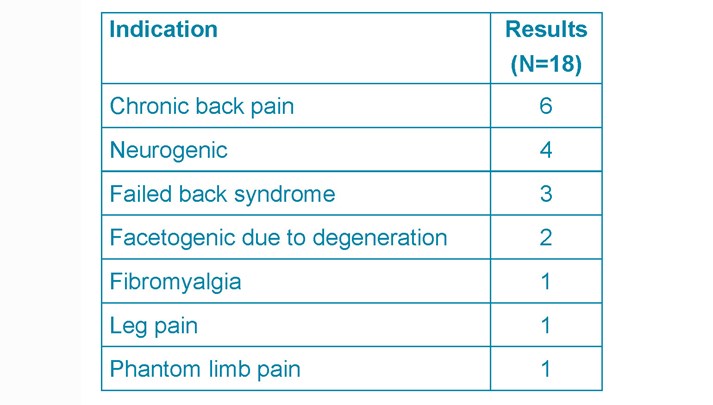

Methods: A retrospective review of indications, dose changes over time, and the complications 14 days post-operatively.

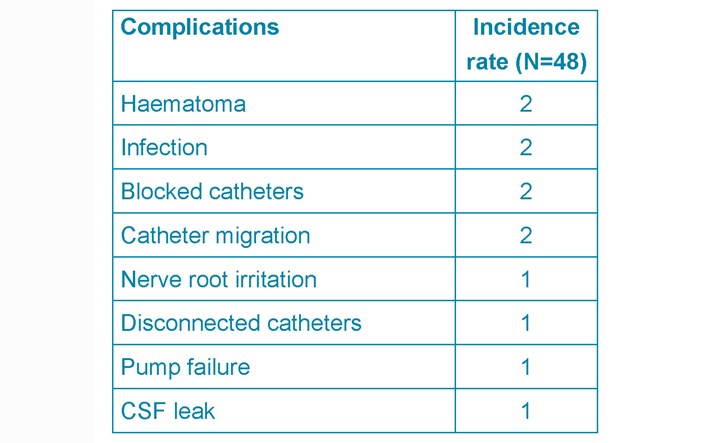

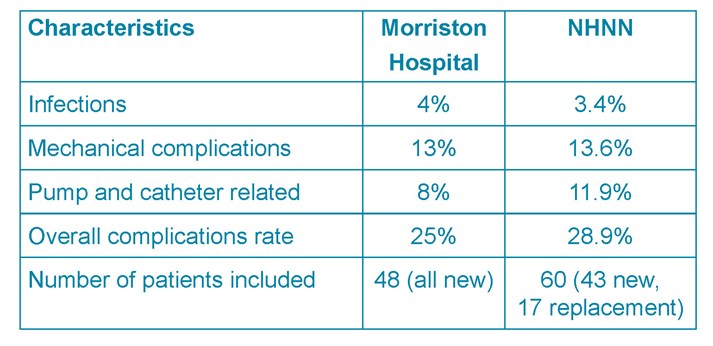

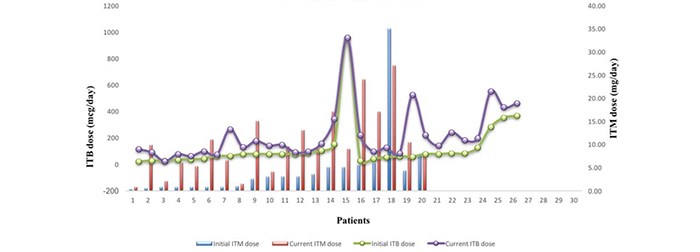

Results: 48 adult patients were included. The overall perioperative complication rate was 24%. 10% were pump related (4 catheter blocks, 1 pump failure), 14% non-pump related (1 CSF leak, 3 haematomas, 2 superficial infections). The mean initial and current ITM doses were 4.27mg/day and 10.4mg/day, and 120.61 mcg/day and 215mcg/day for ITB. Patients rated the service as excellent. 73.4% ranked their QoL improvement moderate (2-4/5) to excellent (5/5). Moderate symptom control satisfaction (3.70/5 (ITB), 3.82/5 (ITM)). Conclusion: These results are comparable to those from the NHNN and current literature (level III evidence). There is a gap between the number of patients eligible for pump implantation and procedures performed per annum. Reviews across the UK including patient surveys are required to set a standard of care and support adequate resource allocation for the continuation of this service.

Introduction